From a History of Genus Mergers to an Overdue Break-Up: a New and Sensible Taxonomy for the Asiatic Wolf Snakes Lycodon Boie, 1826 (Serpentes: Colubridae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genus Lycodon)

Zoologica Scripta Multilocus phylogeny reveals unexpected diversification patterns in Asian wolf snakes (genus Lycodon) CAMERON D. SILER,CARL H. OLIVEROS,ANSSI SANTANEN &RAFE M. BROWN Submitted: 6 September 2012 Siler, C. D., Oliveros, C. H., Santanen, A., Brown, R. M. (2013). Multilocus phylogeny Accepted: 8 December 2012 reveals unexpected diversification patterns in Asian wolf snakes (genus Lycodon). —Zoologica doi:10.1111/zsc.12007 Scripta, 42, 262–277. The diverse group of Asian wolf snakes of the genus Lycodon represents one of many poorly understood radiations of advanced snakes in the superfamily Colubroidea. Outside of three species having previously been represented in higher-level phylogenetic analyses, nothing is known of the relationships among species in this unique, moderately diverse, group. The genus occurs widely from central to Southeast Asia, and contains both widespread species to forms that are endemic to small islands. One-third of the diversity is found in the Philippine archipelago. Both morphological similarity and highly variable diagnostic characters have contributed to confusion over species-level diversity. Additionally, the placement of the genus among genera in the subfamily Colubrinae remains uncertain, although previous studies have supported a close relationship with the genus Dinodon. In this study, we provide the first estimate of phylogenetic relationships within the genus Lycodon using a new multi- locus data set. We provide statistical tests of monophyly based on biogeographic, morpho- logical and taxonomic hypotheses. With few exceptions, we are able to reject many of these hypotheses, indicating a need for taxonomic revisions and a reconsideration of the group's biogeography. Mapping of color patterns on our preferred phylogenetic tree suggests that banded and blotched types have evolved on multiple occasions in the history of the genus, whereas the solid-color (and possibly speckled) morphotype color patterns evolved only once. -

Vol. 25 No. 1 March, 2000 H a M a D R Y a D V O L 25

NO.1 25 M M A A H D A H O V D A Y C R R L 0 0 0 2 VOL. 25NO.1 MARCH, 2000 2% 3% 2% 3% 2% 3% 2% 3% 2% 3% 2% 3% 2% 3% 2% 3% 2% 3% 4% 5% 4% 5% 4% 5% 4% 5% 4% 5% 4% 5% 4% 5% 4% 5% 4% 5% HAMADRYAD Vol. 25. No. 1. March 2000 Date of issue: 31 March 2000 ISSN 0972-205X Contents A. E. GREER & D. G. BROADLEY. Six characters of systematic importance in the scincid lizard genus Mabuya .............................. 1–12 U. MANTHEY & W. DENZER. Description of a new genus, Hypsicalotes gen. nov. (Sauria: Agamidae) from Mt. Kinabalu, North Borneo, with remarks on the generic identity of Gonocephalus schultzewestrumi Urban, 1999 ................13–20 K. VASUDEVAN & S. K. DUTTA. A new species of Rhacophorus (Anura: Rhacophoridae) from the Western Ghats, India .................21–28 O. S. G. PAUWELS, V. WALLACH, O.-A. LAOHAWAT, C. CHIMSUNCHART, P. DAVID & M. J. COX. Ethnozoology of the “ngoo-how-pak-pet” (Serpentes: Typhlopidae) in southern peninsular Thailand ................29–37 S. K. DUTTA & P. RAY. Microhyla sholigari, a new species of microhylid frog (Anura: Microhylidae) from Karnataka, India ....................38–44 Notes R. VYAS. Notes on distribution and breeding ecology of Geckoella collegalensis (Beddome, 1870) ..................................... 45–46 A. M. BAUER. On the identity of Lacerta tjitja Ljungh 1804, a gecko from Java .....46–49 M. F. AHMED & S. K. DUTTA. First record of Polypedates taeniatus (Boulenger, 1906) from Assam, north-eastern India ...................49–50 N. M. ISHWAR. Melanobatrachus indicus Beddome, 1878, resighted at the Anaimalai Hills, southern India ............................. -

Kedar Bhide Its All About Hisssssss

Its all about Hisssssss Kedar Bhide Snake and you § Kill it § Trap it § Push it § Call fire brigade/Police § Call Pest Control § Call snake charmers § Call Snake rescuers/Animal helplines § Live with it Know & I am more understand afraid than about me you I am a wild animal ( Living in state of nature, inhibiting natural haunts, not familiar with ,or not easily approached by Man, not tamed or domesticated),, Web definition of SNAKE 1. Any of numerous scaly, legless, sometimes venomous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes or Ophidia (order Squamata), having a long, tapering, cylindrical body and found in most tropical and temperate regions. 2. A treacherous person. Also called snake in the grass. 3. A long, highly flexible metal wire or coil used for cleaning drains. Also called plumber's snake. 4. Economics A fixing of the value of currencies to each other within defined parameters, which when graphed visually shows these currencies remaining parallel in value to each other as a unit despite fluctuations with other currencies. • Belongs to group of animals called Reptiles ( Class – Reptilia, - Crocodiles, Turtles & Tortoises, Geckos &Lizards) •Limbless reptiles with cylindrical body covered with scales • More than 2900 species in the world, In India represented at the moment by 276 species • Rich diversity in Western Ghats and North East India, many endemic species ( Ecological state of being unique to a particular geographic location) •Ranges from 12 cms to 6 meters, Found in all color forms • Are found in all habitats, terrestrial ( Land) , -

Reptile Field Researchers South Asia

DIRECTORY Of Reptile Field Researchers In South Asia (as of December 2000) Compiled by Sanjay Molur South Asian Reptile Network Zoo Outreach Organisation PB 1683, 29/1 Bharathi Colony Peelamedu, Coimbatore Tamil Nadu, India S.A.R.N. Flora and Fauna International S.A.R.N. DIRECTORY of Reptile Field Researchers in South Asia (as of December 2000) Compiled by Sanjay Molur South Asian Reptile Network Zoo Outreach Organisation PB 1683, 29/1 Bharathi Colony Peelamedu, Coimbatore Tamil Nadu, India Funded by Fauna and Flora International and Columbus Zoo Assisted by South Asian Reptile and Amphibian Specialist Group Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, India Zoo Outreach Organisation For a long time, it was felt that though there were quite a few reptile researchers in India, there was no coordination, cooperation, exchange of information between them. Often only a core group of “well-known” reptile researchers were in communication. The rest of the biologists did their own research in isolation. This, of course, did lead to duplication of work, non-standard methodologies, ambiguity in knowledge, non-accessibility to exotic references, etc. The effects of this situation were obvious at the Conservation Assessment and Management Plan workshop (CAMP) for Reptiles in May 1997. At the workshop, albeit the exercise lead to the assessment of close to 500 taxa of Indian reptiles, a sense of unease was felt by the participants. Many isolated studies on reptiles could not be compared for want of comparable field methodologies, the veracity of the information provided was questioned of an unknown or nervous researcher and the ubiquitous feeling of “if we had all known each other better, we could have come up with more information” were reasons for the group recommending that a network of reptile researchers be formed immediately. -

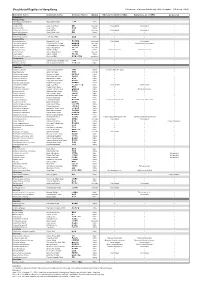

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

A Preliminary Survey on Diversity and Distribution of Snake Fauna in Nalbari District of Assam, North Eastern India

P: ISSN No. 0976-8602 RNI No.UPENG/2012/42622 VOL.-7, ISSUE-3, July-2018 E: ISSN No. 2349 - 9443 AsianA…..A…. Reson ance A Preliminary Survey on Diversity and Distribution of Snake Fauna in Nalbari District of Assam, North Eastern India Abstract Snakes are probably the most misunderstood and universally disliked animals in the world since time immemorial. It is true that bite of some poisonous snakes is sometimes fatal, but most of them are harmless and beneficial to us. Unfortunately, most of our fears about snakes are based on sheer ignorance and baseless superstitions. The Reptilian fauna is one of the targeted faunas facing trouble due to anthropogenic developments (Gibbons et al. 2000). An urban development or expansion victimizes reptiles firstly, ultimately resulting in the deterioration of the fauna by habitat destruction or alteration. Such situation ends up with too many reptilian species co-existing with the urban world (McKinney 2006). This has raised the numbers of reptilian species in the newly developed urban areas located in the outskirts of the city, including numbers of snake species (Purkayastha et al. 2011). A few Bikash Baishya species of snakes have adapted to human habitation, especially in the Research Scholar, suburban backyards, urban gardens, roofed houses (old style) and open Deptt. of Zoology, sewages. Thus, urban habitation acts as advantageous habitat for few University of Science & snake species, in terms of food and shelter. The Indian snake fauna is Technology, very rich and diversified. Whitaker & Captain (2004) listed about 275 Meghalaya species belonging to 11 families of snakes found within the political boundary of India. -

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong Family No. of Species Common Name Scientific Name Order TESTUDOFORMES Cheloniidae 4 Loggerhead Turtle Caretta caretta Green Turtle Chelonia mydas Hawksbill Turtle Eretmochelys imbricata Olive Ridley Turtle Lepidochelys olivacea Dermochelyidae 1 Leatherback Turtle Dermochelys coriacea Emydidae 1 Red-eared Slider * Trachemys scripta elegans Geoemydidae 3 Three-banded Box Turtle Cuora trifasciata Reeves' Turtle Mauremys reevesii Beale's Turtle Sacalia bealei Platysternidae 1 Big-headed Turtle Platysternon megacephalum Trionychidae 1 Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle Pelodiscus sinensis Order SQUAMATA Suborder LACERTILIA Agamidae 1 Changeable Lizard Calotes versicolor Lacertidae 1 Grass Lizard Takydromus sexlineatus ocellatus Scincidae 11 Chinese Forest Skink Ateuchosaurus chinensis Long-tailed Skink Eutropis longicaudata Chinese Skink Plestiodon chinensis chinensis Five-striped Blue-tailed Skink Plestiodon elegans Blue-tailed Skink Plestiodon quadrilineatus Vietnamese Five-lined Skink Plestiodon tamdaoensis Slender Forest Skink Scincella modesta Reeve's Smooth Skink Scincella reevesii Brown Forest Skink Sphenomorphus incognitus Indian Forest Skink Sphenomorphus indicus Chinese Waterside Skink Tropidophorus sinicus Varanidae 1 Common Water Monitor Varanus salvator Dibamidae 1 Bogadek's Burrowing Lizard Dibamus bogadeki Gekkonidae 8 Four-clawed Gecko Gehyra mutilata Chinese Gecko Gekko chinensis Tokay Gecko Gekko gecko Bowring's Gecko Hemidactylus bowringii Brook's Gecko* Hemidactylus brookii House Gecko* Hemidactylus -

New Records and an Updated Checklist of Amphibians and Snakes From

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Bonn zoological Bulletin - früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. Jahr/Year: 2021 Band/Volume: 70 Autor(en)/Author(s): Le Dzung Trung, Luong Anh Mai, Pham Cuong The, Phan Tien Quang, Nguyen Son Lan Hung, Ziegler Thomas, Nguyen Truong Quang Artikel/Article: New records and an updated checklist of amphibians and snakes from Tuyen Quang Province, Vietnam 201-219 Bonn zoological Bulletin 70 (1): 201–219 ISSN 2190–7307 2021 · Le D.T. et al. http://www.zoologicalbulletin.de https://doi.org/10.20363/BZB-2021.70.1.201 Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1DF3ECBF-A4B1-4C05-BC76-1E3C772B4637 New records and an updated checklist of amphibians and snakes from Tuyen Quang Province, Vietnam Dzung Trung Le1, Anh Mai Luong2, Cuong The Pham3, Tien Quang Phan4, Son Lan Hung Nguyen5, Thomas Ziegler6 & Truong Quang Nguyen7, * 1 Ministry of Education and Training, 35 Dai Co Viet Road, Hanoi, Vietnam 2, 5 Hanoi National University of Education, 136 Xuan Thuy Road, Hanoi, Vietnam 2, 3, 7 Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Graduate University of Science and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet Road, Hanoi, Vietnam 6 AG Zoologischer Garten Köln, Riehler Strasse 173, D-50735 Köln, Germany 6 Institut für Zoologie, Universität Köln, Zülpicher Strasse 47b, D-50674 Köln, Germany * Corresponding author: Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:2C2D01BA-E10E-48C5-AE7B-FB8170B2C7D1 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:8F25F198-A0F3-4F30-BE42-9AF3A44E890A 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:24C187A9-8D67-4D0E-A171-1885A25B62D7 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:555DF82E-F461-4EBC-82FA-FFDABE3BFFF2 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:7163AA50-6253-46B7-9536-DE7F8D81A14C 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5716DB92-5FF8-4776-ACC5-BF6FA8C2E1BB 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:822872A6-1C40-461F-AA0B-6A20EE06ADBA Abstract. -

New Records of Snakes and Lizards from Bhutan

Hamadryad Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 25 – 31, 2012. Copyright 2010 Centre for Herpetology, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust. New records of snakes and lizards from Bhutan Jigme Tshelthrim Wangyal College of Natural Resources, Royal University of Bhutan, Lobesa, Punakha, Bhutan E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.– Ten snake species (Ramphotyphlops braminus, Python bivittatus, Lycodon fasciatus, Lycodon aulicus, Lycodon jara, Rhabdophis subminiatus, Chrysopelea ornata, Dendrelaphis tristis, Naja naja, Trimeresurus albolabris) and two lizards (Gekko gecko and Sphenomorphus maculatus) are reported for the first time from Bhutan. With the exception of a few species, most are from the Sarpang District. Data were collected opportunistically and georeferenced. KEYWORDS.– Snakes, lizards, distributional records, Bhutan Introduction port the occurrence of 10 snake species and one Bhutan is a landlocked Himalayan country, ly- lizard from the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan ing between two Asian giants, China and India. (Fig. 1). For each of these records, I provide a A large part of the country is comprised of moun- digital photograph, georeferenced locality data tains and valleys, located on the southern slopes and details of pholidosis, using the Dowling sys- of the Eastern Himalayas. A majority of the Bhu- tem, when relevant. I also provide information tanese are Buddhists and consider reptiles (espe- on where some of the collected materials are ar- cially snakes) as animals that represent anger and chived. jealousy. They also believe that snakes represent deities which live underground, and prefer not Materials and Methods to disturb them. Therefore, most people choose After the publication of a regional reptile report to keep away from reptiles, and it has generally (Wangyal & Tenzin 2009) of Bumdeling Wildlife been presumed locally that the country does not Sanctuary (BWS), Trashiyangtse, collection of require separate measures for reptile conserva- information on the reptiles found in Bhutan was tion. -

Human-Snake Conflict Patterns in a Dense Urban-Forest Mosaic Landscape

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 14(1):143–154. Submitted: 9 June 2018; Accepted: 25 February 2019; Published: 30 April 2019. HUMAN-SNAKE CONFLICT PATTERNS IN A DENSE URBAN-FOREST MOSAIC LANDSCAPE SAM YUE1,3, TIMOTHY C. BONEBRAKE1, AND LUKE GIBSON2 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, China 2School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China 3Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Human expansion and urbanization have caused an escalation in human-wildlife conflicts worldwide. Of particular concern are human-snake conflicts (HSC), which result in over five million reported cases of snakebite annually and significant medical costs. There is an urgent need to understand HSC to mitigate such incidents, especially in Asia, which holds the highest HSC frequency in the world and the highest projected urbanization rate, though knowledge of HSC patterns is currently lacking. Here, we examined the relationships between season, weather, and habitat type on HSC incidents since 2002 in Hong Kong, China, which contains a mixed landscape of forest, dense urban areas, and habitats across a range of human disturbance and forest succession. HSC frequency peaked in the autumn and spring, likely due to increased activity before and after winter brumation. There were no considerable differences between incidents involving venomous and non-venomous species. Dense urban areas had low HSC, likely due to its inhospitable environment for snakes, while forest cover had no discernible influence on HSC. We found that disturbed or lower quality habitats such as shrubland or areas with minimal vegetation had the highest HSC, likely because such areas contain intermediate densities of snakes and humans, and intermediate levels of disturbance. -

Gekkotan Lizard Taxonomy

3% 5% 2% 4% 3% 5% H 2% 4% A M A D R Y 3% 5% A GEKKOTAN LIZARD TAXONOMY 2% 4% D ARNOLD G. KLUGE V O 3% 5% L 2% 4% 26 NO.1 3% 5% 2% 4% 3% 5% 2% 4% J A 3% 5% N 2% 4% U A R Y 3% 5% 2 2% 4% 0 0 1 VOL. 26 NO. 1 JANUARY, 2001 3% 5% 2% 4% INSTRUCTIONS TO CONTRIBUTORS Hamadryad publishes original papers dealing with, but not necessarily restricted to, the herpetology of Asia. Re- views of books and major papers are also published. Manuscripts should be only in English and submitted in triplicate (one original and two copies, along with three cop- ies of all tables and figures), printed or typewritten on one side of the paper. Manuscripts can also be submitted as email file attachments. Papers previously published or submitted for publication elsewhere should not be submitted. Final submissions of accepted papers on disks (IBM-compatible only) are desirable. For general style, contributors are requested to examine the current issue of Hamadryad. Authors with access to publication funds are requested to pay US$ 5 or equivalent per printed page of their papers to help defray production costs. Reprints cost Rs. 2.00 or 10 US cents per page inclusive of postage charges, and should be ordered at the time the paper is accepted. Major papers exceeding four pages (double spaced typescript) should contain the following headings: Title, name and address of author (but not titles and affiliations), Abstract, Key Words (five to 10 words), Introduction, Material and Methods, Results, Discussion, Acknowledgements, Literature Cited (only the references cited in the paper). -

Diversity of Snakes in Rajegwesi Tourism Area, Meru Betiri National Park Aji Dharma Raharjo*, Luchman Hakim

Journal of Indonesian Tourism and E-ISSN : 2338-1647 Development Studies http://jitode.ub.ac.id Diversity of Snakes in Rajegwesi Tourism Area, Meru Betiri National Park Aji Dharma Raharjo*, Luchman Hakim Depertement of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, University of Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia Abstract Rajegwesi tourism area is one of the significant tourism areas in Meru Betiri National Park, East Java, Indonesia. The area rich in term of biodiversity which are potential for developed as natural tourism attraction. The aim of this study is to identify snakes species diversity and its distribution in Rajegwesi tourism area. Field survey was done in Rajegwesi area, namely swamps forest, residential area, rice fields, agriculture area (babatan), resort area, and Plengkang cliff. This study found some snakes, encompasses Colubridae (10 species), Elapidae (four species), and Phytonidae (one species). There are Burmese Python (Python reticulatus), Red-necked Keelback (Rhabdophis subminiatus), Painted Bronzeback Snake (Dendrelaphis Pictus), Black Copper Rat Snake (Coelognathus flavolineatus), Radiated Rat Snake (C. radiatus), Striped Keelback (Xenochrophis vittatus), Checkered Keelback (X. piscator), Spotted Ground Snake (Gongyosoma balioderius), Gold-ringed Cat Snake (Boiga dendrophila), Common Wolf Snake (Lycodon capucinus), Banded Wolf snake (L. subcinctus), Cobra (Naja sputatrix), King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), Malayan Krait (Bungarus candidus), and Banded Krait (B. fasciatus) was found. These snake habitats distributes at 21 coordinate points. Keywords: conservation, ecotourism, snakes. INTRODUCTION* Betiri National Park has several tourism areas; Snakes are legless-carnivorous reptiles living one of them is Rajegwesi, a coastal area. Aim of on every continent except Antarctica and can be this study is to identify snakes species distribu- found in aquatic, arboreal, and terestrial areas tion along Rajegwesi tourism area.