IJTM/IJCEE PAGE Templatev2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2530

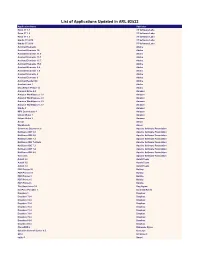

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2530 Application Name Publisher .NET Core SDK 2 Microsoft Acrobat Elements Adobe Acrobat Elements 10 Adobe Acrobat Elements 11.0 Adobe Acrobat Elements 15.1 Adobe Acrobat Elements 15.7 Adobe Acrobat Elements 15.9 Adobe Acrobat Elements 6.0 Adobe Acrobat Elements 7.0 Adobe Application Name Acrobat Elements 8 Adobe Acrobat Elements 9 Adobe Acrobat Reader DC Adobe Acrobat.com 1 Adobe Alchemy OpenText Alchemy 9.0 OpenText Amazon Drive 4.0 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 1.1 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 2.1 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 2.2 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 2.3 Amazon Ansys Ansys Archive Server 10.1 OpenText AutoIt 2.6 AutoIt Team AutoIt 3.0 AutoIt Team AutoIt 3.2 AutoIt Team Azure Data Studio 1.9 Microsoft Azure Information Protection 1.0 Microsoft Captiva Cloud Toolkit 3.0 OpenText Capture Document Extraction OpenText CloneDVD 2 Elaborate Bytes Cognos Business Intelligence Cube Designer 10.2 IBM Cognos Business Intelligence Cube Designer 11.0 IBM Cognos Business Intelligence Cube Designer for Non-Production environment 10.2 IBM Commons Daemon 1.0 Apache Software Foundation Crystal Reports 11.0 SAP Data Explorer 8.6 Informatica DemoCreator 3.5 Wondershare Software Deployment Wizard 9.3 SAS Institute Deployment Wizard 9.4 SAS Institute Desktop Link 9.7 OpenText Desktop Viewer Unspecified OpenText Document Pipeline DocTools 10.5 OpenText Dropbox 1 Dropbox Dropbox 73.4 Dropbox Dropbox 74.4 Dropbox Dropbox 75.4 Dropbox Dropbox 76.4 Dropbox Dropbox 77.4 Dropbox Dropbox 78.4 Dropbox Dropbox 79.4 Dropbox Dropbox 81.4 -

Forensics Evaluation of Privacy of Portable Web Browsers

International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887) Volume 147 – No. 8, August 2016 Forensics Evaluation of Privacy of Portable Web Browsers Ahmad Ghafarian Seyed Amin Hosseini Seno Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Engineering and Information Systems Faculty of Engineering University of North Georgia Ferdowsi University of Mashhad Dahlonega, GA 30005, USA Mashhad, Iran ABSTRACT relation to a computer forensic investigation is that the latter is Browsers claim private mode browsing saves no data on the a less tangible source of evidence [3]. host machine. Most popular web browsers also offer portable A study of tools and techniques for memory forensics can be versions of their browsers which can be launched from a found in [4]. The author has evaluated several command line removable device. When the removable device is removed, it and graphical user interface tools and provide the steps is claimed that traces of browsing activities will be deleted needed for memory forensics. Retrieving portable browsing and consequently private portable browsers offer better forensics artifacts left behind from main memory have privacy. This makes the task of computer forensics recently attracted some attention [5, 6]. The authors used investigators who try to reconstruct the past browsing history, limited memory forensics to retrieve forensics artifacts left in case of any computer incidence, more challenging. after a private portable browsing session. They argue that However, whether or not all data is deleted beyond forensic memory forensics is very promising in establishing a link recovery is a moot point. This research examines privacy of between the suspect and the retrieved data. -

Private Browsing

Away From Prying Eyes: Analyzing Usage and Understanding of Private Browsing Hana Habib, Jessica Colnago, Vidya Gopalakrishnan, Sarah Pearman, Jeremy Thomas, Alessandro Acquisti, Nicolas Christin, and Lorrie Faith Cranor, Carnegie Mellon University https://www.usenix.org/conference/soups2018/presentation/habib-prying This paper is included in the Proceedings of the Fourteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security. August 12–14, 2018 • Baltimore, MD, USA ISBN 978-1-939133-10-6 Open access to the Proceedings of the Fourteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security is sponsored by USENIX. Away From Prying Eyes: Analyzing Usage and Understanding of Private Browsing Hana Habib, Jessica Colnago, Vidya Gopalakrishnan, Sarah Pearman, Jeremy Thomas, Alessandro Acquisti, Nicolas Christin, Lorrie Faith Cranor Carnegie Mellon University {htq, jcolnago, vidyag, spearman, thomasjm, acquisti, nicolasc, lorrie}@andrew.cmu.edu ABSTRACT Prior user studies have examined different aspects of private Previous research has suggested that people use the private browsing, including contexts for using private browsing [4, browsing mode of their web browsers to conduct privacy- 10, 16, 28, 41], general misconceptions of how private brows- sensitive activities online, but have misconceptions about ing technically functions and the protections it offers [10,16], how it works and are likely to overestimate the protections and usability issues with private browsing interfaces [41,44]. it provides. To better understand how private browsing is A major limitation of much prior work is that it is based used and whether users are at risk, we analyzed browsing on self-reported survey data, which may not always be reli- data collected from over 450 participants of the Security able. -

(Hardening) De Navegadores Web Más Utilizados

UNIVERSIDAD DON BOSCO VICERRECTORÍA DE ESTUDIOS DE POSTGRADO TRABAJO DE GRADUACIÓN Endurecimiento (Hardening) de navegadores web más utilizados. Caso práctico: Implementación de navegadores endurecidos (Microsoft Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox y Google Chrome) en un paquete integrado para Microsoft Windows. PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE: MAESTRO EN SEGURIDAD Y GESTION DEL RIESGO INFORMATICO ASESOR: Mg. JOSÉ MAURICIO FLORES AVILÉS PRESENTADO POR: ERICK ALFREDO FLORES AGUILAR Antiguo Cuscatlán, La Libertad, El Salvador, Centroamérica Febrero de 2015 AGRADECIMIENTOS A Dios Todopoderoso, por regalarme vida, salud y determinación para alcanzar un objetivo más en mi vida. A mi amada esposa, que me acompaño durante toda mi carrera, apoyó y comprendió mi dedicación de tiempo y esfuerzo a este proyecto y nunca dudó que lo concluiría con bien. A mis padres y hermana, que siempre han sido mis pilares y me enseñaron que lo mejor que te pueden regalar en la vida es una buena educación. A mis compañeros de trabajo, que mediante su esfuerzo extraordinario me han permitido contar con el tiempo necesario para dedicar mucho más tiempo a la consecución de esta meta. A mis amigos de los que siempre he tenido una palabra de aliento cuando la he necesitado. A mi supervisor y compañeros de la Escuela de Computación de la Universidad de Queens por facilitarme espacio, recursos, tiempo e información valiosa para la elaboración de este trabajo. A mi asesor de tesis, al director del programa de maestría y mis compañeros de la carrera, que durante estos dos años me han ayudado a lograr esta meta tan importante. Erick Alfredo Flores Aguilar INDICE I. -

Tracking Users Across the Web Via TLS Session Resumption

Tracking Users across the Web via TLS Session Resumption Erik Sy Christian Burkert University of Hamburg University of Hamburg Hannes Federrath Mathias Fischer University of Hamburg University of Hamburg ABSTRACT modes, and browser extensions to restrict tracking practices such as User tracking on the Internet can come in various forms, e.g., via HTTP cookies. Browser fingerprinting got more difficult, as trackers cookies or by fingerprinting web browsers. A technique that got can hardly distinguish the fingerprints of mobile browsers. They are less attention so far is user tracking based on TLS and specifically often not as unique as their counterparts on desktop systems [4, 12]. based on the TLS session resumption mechanism. To the best of Tracking based on IP addresses is restricted because of NAT that our knowledge, we are the first that investigate the applicability of causes users to share public IP addresses and it cannot track devices TLS session resumption for user tracking. For that, we evaluated across different networks. As a result, trackers have an increased the configuration of 48 popular browsers and one million of the interest in additional methods for regaining the visibility on the most popular websites. Moreover, we present a so-called prolon- browsing habits of users. The result is a race of arms between gation attack, which allows extending the tracking period beyond trackers as well as privacy-aware users and browser vendors. the lifetime of the session resumption mechanism. To show that One novel tracking technique could be based on TLS session re- under the observed browser configurations tracking via TLS session sumption, which allows abbreviating TLS handshakes by leveraging resumptions is feasible, we also looked into DNS data to understand key material exchanged in an earlier TLS session. -

Forensic Investigation of User's Web Activity on Google Chrome Using

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.16 No.9, September 2016 123 Forensic Investigation of User’s Web Activity on Google Chrome using various Forensic Tools Narmeen Shafqat, NUST, Pakistan Summary acknowledged browsers like Internet Explorer, Google Cyber Crimes are increasing day by day, ranging from Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Safari, Opera etc. but should confidentiality violation to identity theft and much more. The also have hands on experience of less popular web web activity of the suspect, whether carried out on computer or browsers like Erwise, Arena, Cello, Netscape, iCab, smart device, is hence of particular interest to the forensics Cyberdog etc. Not only this, the forensic experts should investigator. Browser forensics i.e forensics of suspect’s browser also know how to find artifacts of interest from older history, saved passwords, cache, recent tabs opened etc. , therefore supply ample amount of information to the forensic versions of well-known web browsers; Internet Explorer, experts in case of any illegal involvement of the culprit in any Chrome and Mozilla Firefox atleast, because he might activity done on web browsers. Owing to the growing popularity experience a case where the suspected person is using and widespread use of the Google Chrome web browser, this older versions of these browsers. paper will forensically analyse the said browser in windows 8 According to StatCounter Global market share for the web environment, using various forensics tools and techniques, with browsers (2015), Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox and the aim to reconstruct the web browsing activities of the suspect. Microsoft’s Internet Explorer make up 90% of the browser The working of Google Chrome in regular mode, private usage. -

Incognito (Private Browsing) for AHA Online Testing

Incognito (private browsing) for AHA Online Testing Go Incognito on Google Chrome 1. Open Google Chrome and click the wrench icon in the top right corner. 2. Click ‘new incognito window’. 3. Alternatively, you can press Ctrl + Shift + N. *You can also open a link in a web page in Incognito Mode. 1. Right-click on the link you want to open in an Incognito window. 2. Click ’Open in new incognito window’ from the context menu. **You can tell if you’re browsing privately by looking for the logo of the person in disguise in the top-left corner of the window. He’s wearing sunglasses, a hat and a raincoat. Go Incognito on Mozilla Firefox 1. Open Firefox and click the hamburger Menu button – it looks like three parallel lines. 2. Click ‘New private window’. *You can also open a link in a web page in a private window. 1. Right-click on the link you want to open in a private window. 2. Click ’Open in New Private Window’ from the context menu. **You can tell if you’re browsing privately by looking for an icon of a purple mask in the top-right corner of the window. Go Incognito on Safari on the Mac 1. In Yosemite and later, open Safari and click on ‘File’. 2. Click ‘New Private Window’. 3. Alternatively, click Command + Shift + N. 4. In Mavericks 10.9 or older, open Safari and click Safari in the browser’s Menu bar and select ‘Private Browsing’. **Private browsing tabs in Safari are separated from non-private tabs. -

An Analysis of Private Browsing Modes in Modern Browsers

An Analysis of Private Browsing Modes in Modern Browsers Gaurav Aggarwal Elie Bursztein Collin Jackson Dan Boneh Stanford University CMU Stanford University Abstract Even within a single browser there are inconsistencies. We study the security and privacy of private browsing For example, in Firefox 3.6, cookies set in public mode modes recently added to all major browsers. We first pro- are not available to the web site while the browser is in pose a clean definition of the goals of private browsing private mode. However, passwords and SSL client cer- and survey its implementation in different browsers. We tificates stored in public mode are available while in pri- conduct a measurement study to determine how often it is vate mode. Since web sites can use the password man- used and on what categories of sites. Our results suggest ager as a crude cookie mechanism, the password policy that private browsing is used differently from how it is is inconsistent with the cookie policy. marketed. We then describe an automated technique for Browser plug-ins and extensions add considerable testing the security of private browsing modes and report complexity to private browsing. Even if a browser ad- on a few weaknesses found in the Firefox browser. Fi- equately implements private browsing, an extension can nally, we show that many popular browser extensions and completely undermine its privacy guarantees. In Sec- plugins undermine the security of private browsing. We tion 6.1 we show that many widely used extensions un- propose and experiment with a workable policy that lets dermine the goals of private browsing. -

Features Guide [email protected] Table of Contents

Features Guide [email protected] Table of Contents About Us .................................................................................. 3 Make Firefox Yours ............................................................... 4 Privacy and Security ...........................................................10 The Web is the Platform ...................................................11 Developer Tools ..................................................................13 2 About Us About Mozilla Mozilla is a global community with a mission to put the power of the Web in people’s hands. As a nonprofit organization, Mozilla has been a pioneer and advocate for the Web for more than 15 years and is focused on creating open standards that enable innovation and advance the Web as a platform for all. We are committed to delivering choice and control in products that people love and can take across multiple platforms and devices. For more information, visit www.mozilla.org. About Firefox Firefox is the trusted Web browser of choice for half a billion people around the world. At Mozilla, we design Firefox for how you use the Web. We make Firefox completely customizable so you can be in control of creating your best Web experience. Firefox has a streamlined and extremely intuitive design to let you focus on any content, app or website - a perfect balance of simplicity and power. Firefox makes it easy to use the Web the way you want and offers leading privacy and security features to help keep you safe and protect your privacy online. Mozilla continues to move the Web forward by pioneering new open source technologies such as asm.js, Emscripten and WebAPIs. Firefox also has a range of amazing built-in developer tools to provide a friction-free environment for building Web apps and Web content. -

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2532

List of Applications Updated in ARL #2532 Application Name Publisher Robo 3T 1.1 3T Software Labs Robo 3T 1.2 3T Software Labs Robo 3T 1.3 3T Software Labs Studio 3T 2018 3T Software Labs Studio 3T 2019 3T Software Labs Acrobat Elements Adobe Acrobat Elements 10 Adobe Acrobat Elements 11.0 Adobe Acrobat Elements 15.1 Adobe Acrobat Elements 15.7 Adobe Acrobat Elements 15.9 Adobe Acrobat Elements 6.0 Adobe Acrobat Elements 7.0 Adobe Acrobat Elements 8 Adobe Acrobat Elements 9 Adobe Acrobat Reader DC Adobe Acrobat.com 1 Adobe Shockwave Player 12 Adobe Amazon Drive 4.0 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 1.1 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 2.1 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 2.2 Amazon Amazon WorkSpaces 2.3 Amazon Kindle 1 Amazon MP3 Downloader 1 Amazon Unbox Video 1 Amazon Unbox Video 2 Amazon Ansys Ansys Workbench Ansys Commons Daemon 1.0 Apache Software Foundation NetBeans IDE 5.0 Apache Software Foundation NetBeans IDE 5.5 Apache Software Foundation NetBeans IDE 7.2 Apache Software Foundation NetBeans IDE 7.2 Beta Apache Software Foundation NetBeans IDE 7.3 Apache Software Foundation NetBeans IDE 7.4 Apache Software Foundation NetBeans IDE 8.0 Apache Software Foundation Tomcat 5 Apache Software Foundation AutoIt 2.6 AutoIt Team AutoIt 3.0 AutoIt Team AutoIt 3.2 AutoIt Team PDF Printer 10 Bullzip PDF Printer 11 Bullzip PDF Printer 3 Bullzip PDF Printer 5 Bullzip PDF Printer 6 Bullzip The Unarchiver 3.1 Dag Agren KeePass Portable 1 Dominik Reichl Dropbox 1 Dropbox Dropbox 73.4 Dropbox Dropbox 74.4 Dropbox Dropbox 75.4 Dropbox Dropbox 76.4 Dropbox Dropbox 77.4 Dropbox -

Online Tracking: a 1-Million-Site Measurement and Analysis

Online Tracking: A 1-million-site Measurement and Analysis Steven Englehardt Arvind Narayanan Princeton University Princeton University This is an extended version of our paper that appeared at ACM CCS 2016. ABSTRACT to resort to a stripped-down browser [31] (a limitation we explore in detail in Section 3.3). (2) We provide compre We present the largest and most detailed measurement of hensive instrumentation by expanding on the rich browser online tracking conducted to date, based on a crawl of the extension instrumentation of FourthParty [33], without re top 1 million websites. We make 15 types of measurements quiring the researcher to write their own automation code. on each site, including stateful (cookie-based) and stateless (3) We reduce duplication of work by providing a modular (fingerprinting-based) tracking, the effect of browser privacy architecture to enable code re-use between studies. tools, and the exchange of tracking data between different Solving these problems is hard because the web is not de sites (“cookie syncing”). Our findings include multiple so 2 signed for automation or instrumentation. Selenium, the phisticated fingerprinting techniques never before measured main tool for automated browsing through a full-fledged in the wild. browser, is intended for developers to test their own web This measurement is made possible by our open-source 1 sites. As a result it performs poorly on websites not con web privacy measurement tool, OpenWPM , which uses an trolled by the user and breaks frequently if used for large- automated version of a full-fledged consumer browser. It scale measurements. Browsers themselves tend to suffer supports parallelism for speed and scale, automatic recovery memory leaks over long sessions. -

Private Browsing

MyChart Troubleshooting Guide Private Browsing Private Browsing helps prevent your browsing history, temporary Internet files, form data, cookies, and user names and passwords from being retained by the browser. This functionality is a good idea to use on a public/shared computer but it can also help isolate your browser and ensure that installed plugins or add-ons can’t interfere with the user’s browser session. Internet Explorer – Directions to turn on: InPrivate Browsing http://windows.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/inprivate-faq#1TC=windows-7 To turn on InPrivate Browsing, complete the following steps: Double click on the Internet Explorer icon to open a new browsing session. Click the Tools icon ; click Safety, then click InPrivate Browsing. Open a new Internet tab by clicking this icon . You should now see an InPrivate indicator next to the URL bar. Any website that you enter in the URL bar will be InPrivate mode. Mozilla Firefox – Directions to turn on: Private Browsing https://support.mozilla.org/en-US/kb/private-browsing-browse-web-without-saving-info To turn on Private Browsing, do any of the following: Double click on the Mozilla Firefox icon to open a new browsing session. Click the menu button and then click on New Private Window. Open a new Internet tab by clicking this icon . You should now see a Private Browsing indicator next to the URL bar. Any website that you enter in the URL bar will be in Private Browsing mode. Google Chrome – Directions to turn on: Incognito Mode https://support.google.com/chrome/answer/95464?hl=en To turn on incognito mode, do any of the following: Double click on the Google Chrome icon to open a new browsing session.