Association for Consumer Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panini Adrenalyn XL Manchester United 2011/2012

www.soccercardindex.com 2011/2012 Panini Adrenalyn XL Manchester United checklist Goalkeeper 051 Luis Nani Star Defender 001 David de Gea 052 Paul Pogba 102 Rio Ferdinand 002 Tomasz Kuszczak 053 Federico Macheda 103 Nemanja Vidic 003 Anders Lindegaard 054 Ashley Young 104 Patrice Evra 004 Ben Amos 055 Javier Hernandez 056 Dimitar Berbatov Midfield Marshall Home Kit 057 Wayne Rooney 105 Ryan Giggs 005 Patrice Evra 058 Danny Wellbeck 106 Michael Carrick 006 Rio Ferdinand 059 Michael Owen 107 Ji-sung Park 007 Nemanja Vidic 060 Mame Biram Diouf 008 Rafael da Silva Target Man 009 Fabio da Silva Squad (Foil) 108 Michael Owen 010 Chris Smalling 061 David de Gea 109 Dimitar Berbatov 011 Jonny Evans 062 Tomasz Kuszczak 110 Danny Wellbeck 012 Phil Jones 063 Anders Lindegaard 013 Tom Cleverly 064 Ben Amos Safe Hands (Ultimate foil) 014 Michael Carrick 065 Patrice Evra 111 David de Gea 015 Ryan Giggs 066 Rio Ferdinand 112 Tomasz Kuszczak 016 Anderson 067 Nemanja Vidic 017 Ji-sung Park 068 Rafael da Silva Fans’ Favourite (Ultimate foil) 018 Darren Fletcher 069 Fabio da Silva 113.Ji-sung Park 019 Darren Gibson 070 Chris Smalling 114 Javier Hernandez 020 Antonio Valencia 071 Jonny Evans 021 Luis Nani 072 Phil Jones Star Player (Ultimate foil) 022 Paul Pogba 073 Tom Cleverly 115 Rio Ferdinand 023 Federico Macheda 074 Michael Carrick 116 Ryan Giggs 024 Ashley Young 075 Ryan Giggs 117 Luis Nani 025 Javier Hernandez 076 Anderson 118 Wayne Rooney 026 Dimitar Berbatov 077 Ji-sung Park 027 Wayne Rooney 078 Darren Fletcher Super Striker (Ultimate foil) 028 -

A Brief History of Sports

CLUB LEGENDS TURNED MANAGERS After Ole Gunnar Solskjaer was appointed as Manchester United manager on a permanent basis, we take a look at how other club legends have fared when sat in the managerial hot-seat. 1 K E N N Y D A L G L I S H ( 1 9 8 5 - 1 9 9 1 , 2 0 1 1 - 2 0 1 2 ) L I V E R P O O L Having already endured a successful eight years as a player at Anfield, Dalglish took over from Joe Fagan where he combined his playing career with managerial duties. In his time in charge he won nine trophies, including the league and cup double in the first season. Following a poor run of form with Roy Hogdson, Dalglish returned as manager in January 2011, but this spell was much less successful than the previous, with the only success being in the League Cup. Win ratio: 60.9%, 47.3% 2 J O E R O Y L E ( 1 9 9 4 - 1 9 9 7 ) E V E R T O N Royle, who scored over 100 goals while playing up front for the Toffee's in the 60's and 70's, became manager of the Goodison Park club 20 years after he left them as a player. Despite only being in charge for three years, he led the club to FA Cup glory which is coincidentally their most recent trophy. Win ratio: 39.83% 3 B R Y A N G U N N ( 2 0 0 9 ) N O R W I C H Gunn, who endured over a decade as a goalkeeper for the East Anglian side, was tasked with trying to save Norwich from relegation to League One. -

Goalden Times: December, 2011 Edition

GOALDEN TIMES 0 December, 2011 1 GOALDEN TIMES Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Neena Majumdar & Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: Goalden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes December, 2011 GOALDEN TIMES 2 GT December 2011 Team P.S. Special Thanks to Tulika Das for her contribution in the Compile&Publish Process December, 2011 3 GOALDEN TIMES | Edition V | First Whistle …………5 Goalden Times is all set for the New Year Euro 2012 Group Preview …………7 Building up towards EURO 2012 in Poland-Ukraine, we review one group at a time, starting with Group A. Is the easiest group really 'easy'? ‘Glory’ – We, the Hunters …………18 The internet-based football forums treat them as pests. But does a glory hunter really have anything to be ashamed of? Hengul -

Date: 9 January 2011 Opposition: Manchester United

Date: 9 January 2011 Times Guardian Mail January9 2011 Opposition: Manchester United Telegraph Independent Mirror Echo Competition: FA Cup Dalglish is taken back to the future Defeated Dalglish returns with a rant: Liverpool manager furious at Manchester United 1 Giggs 2 (pen) Liverpool 0 Referee:HWebb. Attendance: penalty and red card: Gerrard was 'reckless' says Ferguson after 1-0 74,727 TONY BARRETT The most compelling argument against Kenny Dalglish's return to Liverpool is that the game has moved on in the two decades since he victory left the club. Conflicting evidence was put forward yesterday to suggest that the There was no triumphant return as Liverpool manager for Kenny Dalglish, only the more things change, the more they stay the same. familiarity of a dispute with Sir Alex Ferguson as he condemned the decisions that Ryan Giggs was less than a fortnight away from the league debut that launched a gave Manchester United victory in the third round of the FA Cup. stellar career when Dalglish walked away from Anfield on February 22, 1991. With Dalglish's first game as Liverpool manager for almost 20 years ended in both anniversaries approaching, it was Giggs who took Dalglish back to the future controversial defeat after the referee, Howard Webb, awarded a first-minute in the cruellest fashion, scoring the decisive penalty that cut short the penalty that enabled Ryan Giggs to decide the contest and dismissed Steven celebrations that had greeted the return of King Kenny and Liverpool's hopes of Gerrard in the 32nd minute for a two-footed tackle on Michael Carrick. -

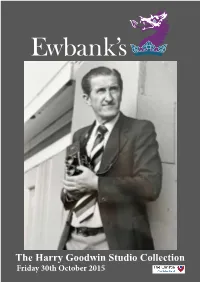

The Harry Goodwin Studio Collection

The Harry Goodwin Studio Collection Friday 30th October 2015 Chris Ewbank, FRICS ASFAV Andrew Ewbank, BA ASFAV Alastair McCrea, MA Senior partner Partner Partner, Entertainment, [email protected] [email protected] Memorabilia and Photography Specialist [email protected] John Snape, BA ASFAV Andrew Delve, MA ASFAV Tim Duggan, ASFAV Partner Partner Partner [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] THE HARRY GOODWIN STUDIO COLLECTION Surrey’s premier antique and fine art auction rooms THE HARRY GOODWIN STUDIO COLLECTION A lifetime photographing pop and sporting stars, over 20,000 images, most sold with full copyright SALE: Friday 30th October 2015 at 12noon VIEWING: Selected lots on view at the Manchester ARTZU Gallery: October 15th & 16th Full viewing at Ewbank’s Surrey Saleroom: Wednesday 28th October 10.00am - 5.00pm Thursday 29th October 10.00am - 5.00pm Morning of sale For the fully illustrated catalogue, to leave commission bids, and to register for Ewbank’s Live Internet Bidding please visit our new website www.ewbankauctions.co.uk The Burnt Common Auction Rooms London Road, Send, Surrey GU23 7LN Tel +44 (0)1483 223101 E-mail: [email protected] Buyers Premium 27% inclusive of VAT An unreserved auction with the hammer price for each lot sold going to the Christie NHS Foundation Trust MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF FINE ART AUCTIONEERS AND VALUERS FOUNDER MEMBERS OF THE ASSOCIATION OF ACCREDITED AUCTIONEERS http://twitter.com/EwbankAuctions www.facebook.com/Ewbanks1 INFORMATION FOR BUYERS 1. Introduction.The following informative notes are intended to assist Buyers, particularly those inexperienced or new to our salerooms. -

Sample Download

Contents Prologue: There We Were 7 1. In Manchester – Part I 17 2 Dancing in the Streets 47 3. Our Friends in the North 59 4. A Stadium for the 90s 88 5. Football’s Coming Home 106 6 The Flickering Flame 122 7. Revolution 166 8 In Manchester – Part II 199 Epilogue: Here We Are 235 Acknowledgements 241 Bibliography 243 1 In Manchester – Part I Off Their Perch By the time Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United visited Carrow Road to face Norwich City in early April 1993, they sat third in the Premier League table, two points behind their hosts and four behind Aston Villa who were leading them all That evening, the performance United gave in front of the Sky cameras for Monday Night Football was breathtakingly devastating, clinical and winning – all that was good about the side that Ferguson had built In their green-and-yellow change strip, a nod to the club’s Newton Heath origins, they destroyed Norwich in the first 21 minutes of the game, blowing them away with three superb, counter-attacking goals Ryan Giggs opened the scoring, Andrei Kanchelskis made it 2-0, and then, after Paul Ince had intercepted the ball inside his own half, the midfielder charged forward and played it across the box to their French maestro forward Eric Cantona for 3-0 ‘United were fantastic that night,’ says fan Andy Walsh from the comfort of his living room in his neat semi-detached Stretford house ‘Really blistering There 17 When the Seagulls Follow the Trawler was a swagger about them that night They were just on another planet ’ United were searching for their first -

Fa Youth Cup

FA YOUTH CUP FIRST ROUND QUALIFYING PORTISHEAD TOWN VS THURSDAY 24TH SEPTEMBER 2020 Kick Off 19.00 p.m. A WELCOME TO TRURO CITY We would like to welcome all players, staff and supporters of Truro City to Bristol Road. Truro City U18 have only just been reformed, with the aim for the Truro Under 18’s to produce players for the first team. The Portishead Town Under 18's competed in the 2019-20 Western Counties Floodlight League North Division, before it was cancelled due to COVID-19. Good luck to both teams in the FA Youth cup tonight. 0800 030 4461 [email protected] FA YOUTH CUP HISTORY The Football Association Youth Challenge Cup is an English football competition run by The Football Association for under-18 sides. Only those players between the age of 15 and 18 on 31 August of the current season are eligible to take part. It is dominated by the youth sides of professional teams, mostly from the Premier League, but attracts over 400 entrants from throughout the country. At the end of the Second World War the FA organised a Youth Championship for County Associations considering it the best way to stimulate the game among those youngsters not yet old enough to play senior football. The matches did not attract large crowds but outstanding players were selected for Youth Internationals and thousands were given the chance to play in a national contest for the first time. In 1951 it was realised that a competition for clubs would probably have a wider appeal. -

The Transformation of Elite-Level Association Football in England, 1970 to the Present

1 The Transformation of Elite-Level Association Football in England, 1970 to the present Mark Sampson PhD Thesis Queen Mary University of London 2 Statement of Originality I, Mark Sampson, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also ackn owledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: M. Sampson Date: 30 June 2016 3 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to provide the first academic account and analysis of the vast changes that took place in English professional football at the top level from 1970 to the present day. It examines the factors that drove those changes both within football and more broadly in English society during this period. The primary sources utilised for this study include newspapers, reports from government inquiries, football fan magazines, memoirs, and oral histories, inter alia. -

SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES Bestseller International Bestseller

4color process, CMYK matte lamination + spot gloss (p.2) + emboss (p.3) SPORTS/SOCCER SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER “As an avid fan of the game and a fi rm believer in the power that such objective namEd onE oF thE “bEst booKs oF thE yEar” BY GUARDIAN, SLATE, analysis can bring to sports, I was captivated by this book. Soccernomics is an FINANCIAL TIMES, INDEPENDENT (UK), AND BLOOMBERG NEWS absolute must-read.” —BillY BEANE, General Manager of the Oakland A’s SOCCERNOMICS pioneers a new way of looking at soccer through meticulous, empirical analysis and incisive, witty commentary. The San Francisco Chronicle describes it as “the most intelligent book ever written about soccer.” This World Cup edition features new material, including a provocative examination of how soccer SOCCERNOMICS clubs might actually start making profi ts, why that’s undesirable, and how soccer’s never had it so good. WHY ENGLAND LOSES, WHY SPAIN, GERMANY, “read this book.” —New York Times AND BRAZIL WIN, AND WHY THE US, JAPAN, aUstralia– AND EVEN IRAQ–ARE DESTINED “gripping and essential.” —Slate “ Quite magnificent. A sort of Freakonomics TO BECOME THE kings of the world’s for soccer.” —JONATHAN WILSON, Guardian MOST POPULAR SPORT STEFAN SZYMANSKI STEFAN SIMON KUPER SIMON kupER is one of the world’s leading writers on soccer. The winner of the William Hill Prize for sports book of the year in Britain, Kuper writes a weekly column for the Financial Times. He lives in Paris, France. StEfaN SzyMaNSkI is the Stephen J. Galetti Collegiate Professor of Sport Management at the University of Michigan’s School of Kinesiology. -

Every Week Manchester United Foundation Is Going to Bring You An

Every week Manchester United Foundation is going to bring you an activity sheet to work through to keep your mind active and have fun whilst we are all staying at home and staying safe. PRINT ME OUT IF YOU CAN, OR MARK ME UP ON Crossword YOUR SMART Using the clues below, fill in the crossword with players PHONE OR TABLET from the current Manchester United first-team squad. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ACROSS DOWN 1. Who made their Brazilian debut in 2014? (4) 2. Who made his United debut in 2011 and has made 394 appearances? (6) 3. Who was born on 5th March 1993? (7) 3. Who made his debut for the first team away at 5. Who is 24 years old and has made Arsenal in May 2017? (5) 132 appearances? (4) 4. Who was an international youth player for the 7. What is the first name of the top goal scorer in Netherlands? (5) the U18 Premier League North in 2017/18? (5) 6. Who was a homegrown youth product for 8. Who is a Spanish midfielder with 48 Manchester United, now aged 22? (8) goals for United? (4) 9. Who is a Swedish defender? (8) Down: 2. De Gea 3. McTominay 4. Chong 6. Rashford 6. Chong 4. McTominay 3. Gea De 2. Down: Lindelof 9. Mata 8. Mason 7. Shaw 5. Maguire 3. Fred 1. Across: Create your own United alphabet Can you come up with a Manchester United themed word for each letter of the alphabet? Write your answers below. -

The Premier League Quiz Book: a Short Football History by Freepubquiz.Co.Uk

The Premier League Quiz Book: A Short Football History By FreePubQuiz.co.uk Copyright © 2016 by FreePubQuiz.co.uk Digital Editions Copyright © 2016 by FreePubQuiz.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Season 1992-93 1. Name the northernmost club to play in the inaugural Premiership? 2. The top three scorers for this season came from Nottingham Forrest/Tottenham Hotspur, QPR, and Wimbledon; can you name them? 3. Who was the only manager to be dismissed from his job during the season? 4. Which club signed Newcastle striker Mickey Quinn in November, and he responded by scoring 17 Premier League goals (the first 10 in 6 games) to keep them clear of relegation? 5. Which club was managed by Mike Walker and captained by Ian Butterworth? 6. What position did Brian Clough's Nottingham Forrest finish? 7. Which team, in the top division for the first time in almost 30 years, finished in fourth place? 8. Which 19 year old won the Young Player of the Year award? 9. Which club finally reached the top flight of English football at the end of this season by beating Leicester City 4–3 in the Division One playoff final, they had been denied promotion three years earlier because of financial irregularities? 10. The Professional Footballers' Association (PFA) presented its annual Player of the Year award to which Aston Villa Player? And who came second and third? Answers: 1. -

P20 Layout 1

Heat scorch Spurs up against Cavaliers Benfica as Fiorentina take on Juventus THURSDAY, MARCH 20, 2014 16 19 Court hears Pistorius shot his girlfriend in hip before head Page 17 OLD TRAFFORD: Manchester United’s Robin van Persie celebrates with teammate Wayne Rooney, after scoring his side’s third goal and his hat-trick, during the Champions League, Round of 16, second leg match against Olympiakos. — AP Van the man for United MANCHESTER: Robin van Persie scored a hat- ducing a fine double save shortly before Van have ruled them out of the first leg in the a stunning double save to thwart David Fuster out with senior players including Ryan Giggs trick as Manchester United kept their season Persie levelled the tie in first-half injury time. quarter-finals, but they worried United on the and Dominguez. and Robin van Persie. alive by storming back to beat Olympiakos 3-0 United’s progress will ease the pressure on counter-attack. Within minutes the tie was level, as Giggs- “A lot of people are trying to divide us in and reach the Champions League quarter- manager David Moyes, whose position was A low Jose Holebas cross had to be hacked again-freed Rooney with a lofted ball into the some way or not keep us together,” Moyes told finals yesterday. the subject of intense press speculation prior clear by Phil Jones, while Hernan Perez should inside-right channel and the England man the club’s television channel, MUTV. “I can only United were left on the brink of elimination to kick-off, but he will remain under scrutiny have done better than hoist the ball high and centred for Van Persie to slam home.