Download Complete Article [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI O.A No.205 of 2013 CORAM: APPLICANT

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI O.A No.205 OF 2013 FRIDAY, THE 20TH DAY OF JUNE, 2014/30TH JYAISHTA, 1936 CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SHRIKANT TRIPATHI, MEMBER (J) HON'BLE VICE ADMIRAL M.P.MURALIDHARAN, AVSM & BAR, NM, MEMBER(A) APPLICANT:- NO.2619339 M EX-SEPOY JUSTIN GEORGE, 27 MADRAS REGIMENT, AGED 21 YEARS, S/O. SHRI CHACKO VARKEY, VAYALILL HOUSE, ELAMAKAD PO., KOTTAYAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE – 686 514. BY ADV. SHRI. RAMESH.C.R. versus RESPONDENTS: 1. THE UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. 2. THE CHIEF OF ARMY STAFF, DHQ PO., INTEGRATED HQRS., MINISTRY OF DEFENCE, SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 011. 3. THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, AG'S BRANCH, ARMY HEADQUARTERS, DHQ PO., NEW DELHI -110 011. 4. THE OIC., RECORDS, THE MADRAS REGT., WELLINGTON, TAMIL NADU – 643 231. 5. THE COMMANDING OFFICER, 27 MADRAS, C/O 56 APO, PIN- 911 427. BY ADV. SRI. P.J.PHIILIP, CENTRAL GOVT. COUNSEL. O.A. No.205 of 2013 - 2 - ORDER Shrikant Tripathi, Member (J): 1. Heard Mr.Ramesh C.R. for the applicant and Mr.P.J.Philip for the respondents and perused the record. 2. The applicant, EX-SEPOY JUSTIN GEORGE, NO.2619339 M has challenged his discharge from the Army and has prayed for his re- instatement in service with full benefits of pay and allowances. He was enrolled in the Indian Army as a Soldier on 18th March 2011. While he was posted to 27th Madras Regiment, he applied for discharge under Army Rule 13 (3) III (iv), which was allowed. -

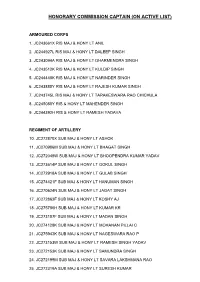

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

James Annesley of Madras Medical Service (1800-1838) on Cholera in Madras Presidency in 1825

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Medical Papers and Journal Articles School of Medicine 2019 James Annesley of Madras Medical Service (1800-1838) on cholera in Madras Presidency in 1825 Ramya Raman The University of Notre Dame Australia Anantanarayanan Raman The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/med_article This article was originally published as: Raman, R., & Raman, A. (2019). James Annesley of Madras Medical Service (1800-1838) on cholera in Madras Presidency in 1825. Current Science, 116 (6). Original article available here: https://www.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/116/06/1026.pdf This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/med_article/1024. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This published version of the article published in Current Science: James Annesley of Madras Medical Service (1800-1838) on cholera in Madras Presidency in 1825. Ramya Raman and Anantanarayanan Raman. CURRENT SCIENCE, 25 March 2019, Vol. 116(6), pp. 1026–1030. Published version available: https://www.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/116/06/1026.pdf HISTORICAL NOTES James Annesley of Madras Medical Service (1800–1838) on cholera in Madras Presidency in 1825 Ramya Raman and Anantanarayanan Raman James Annesley from Ireland spent nearly four decades in Madras, first as an assistant and later as a senior surgeon attached to the Madras Medical Establishment. During this span of service he published the book in 1825 on the most prevalent diseases of India comprising a treatise on the epidemic cholera of the East. This paper recounts the epidemiology of cholera and the efforts made to manage it in the Madras Presidency in the 1820s, keeping in view the life of Annesley and the contents of his book. -

![5 Indian Infantry Division (1943-45)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9374/5-indian-infantry-division-1943-45-1219374.webp)

5 Indian Infantry Division (1943-45)]

1 January 2019 [5 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943-45)] th 5 Indian Infantry Division (1) Main Headquarters 5th Indian Division Rear Headquarters, 5th Indian Division 9th Indian Infantry Brigade Headquarters 9th Indian Infantry Brigade, Signal Section & Light Aid Detachment 2nd Bn. The West Yorkshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s Own) 3rd Bn. 9th Jat Regiment (2) 3rd Bn. 14th Punjab Regiment (3) 123rd Indian Infantry Brigade Headquarters 123rd Indian Infantry Brigade, Signal Section & Light Aid Detachment 2nd Bn. The Suffolk Regiment (4) 2nd Bn. 1st Punjab Regiment (5) 1st (Prince of Wales’s Own) Bn. 17th Dogra Regiment 161st Indian Infantry Brigade (6) Headquarters 161st Indian Infantry Brigade, Signal Section & Light Aid Detachment 4th Bn. The Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment 1st Bn. 1st Punjab Regiment 4th Bn. 7th Rajput Regiment Divisional Troops 3rd Bn. 2nd Punjab Regiment (7) Headquarters, 5th Indian Divisional Royal Artillery 4th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (H.Q., Signal Section & L.A.D., 7th, 14th/66th & 522nd Field Batteries, Royal Artillery) 28th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (8) (H.Q., Signal Section & L.A.D., 1st, 3rd & 5th/57th Field Batteries, Royal Artillery) 56th (King’s Own) Light Anti-Aircraft/Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery (9) (H.Q., 163rd & 164th Light Anti-Aircraft, and 221st & 222nd Anti-Tank Batteries, Royal Artillery) 24th Indian Mountain Regiment, Indian Artillery (6) (H.Q., 2nd (Derajat), 11th (Dehra Dun), 12th (Poonch) & 20th Indian Mountain Batteries, Indian Artillery) ©www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk -

Bit Ncc About the Institution

123 BIT NCC ABOUT THE INSTITUTION The Bannari Amman Institute of Technology is an Auton- 1999 omous Engineering College located in Sathyamangalam, Erode district, Tamil Nadu, India. It is under the roof of Since Bannari Amman Group (BAG), which is one of the largest Industrial Conglomerates in South India with a wide spec- Dr S V BALASUBRAMANIAM trum of manufacturing, trading and service activities. It was CHAIRMAN established by the Bannari Amman Group in 1996 and is affiliated to Anna University. It is located in the lap of luxury with all amenities, in the hub of Eastern and Western Ghats. The institute offers 20 undergraduate and 15 postgradu- ate programmes in Engineering and Management stud- ies. All the departments of Engineering and Technology are recognized by Anna University, Chennai to offer Ph.D. programmes. The institution is ISO 9001:2000 certified Dr M P VIJAYAKUMAR (Rtrd IAS) for its quality education, and most of the eligible courses TRUSTEE are accredited by National Board of Accreditation (NBA), New Delhi and NAAC with “A” Grade. BIT focuses more on the attributes such as eminence, teamwork, innovation, entrepreneurship, courage, sac- rifice and duty that are chiseled on the architraves of granite pavilions. BIT has stretched its wings towards the horizon of success through various administrative and Dr C PALANISAMY academic reformations. This is aimed at catering to the PRINCIPAL needs of the students and members of faculty in the in- stitute. The institute has been conferred with a number of accolades and recognitions from various forums of high eminence. Dr K SIVAKUMAR 123 DEAN - PDS CONTENTS 1999 RAJPATH 2019 - 2020 CARRER RDC GUIDANCE Since Cadet Under His powerful Officer Harini.N speech motivat- participated in CERTIFICATION ed the SSB aspi- RDC,Delhi 2020 EXAMS rants and UPSC representing BIT NCC cadets preparing aspi- TN,P& AN rants. -

ANNEXURE 10.1 CHAPTER X, PARA 17 ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 State (S11) KERALA No

ANNEXURE 10.1 CHAPTER X, PARA 17 ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 State (S11) KERALA No. Name and Reservation Status of Assembly 37 MANJERI Last Part : 170 Constituency : No. Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary 6 MALAPPURAM Service Electors Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located : 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2017 Type of Revision : SPECIAL SUMMARY REVISION Qualifying Date : 01-01-2017 Date of Final Publication : 10-01-2017 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS : 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service Number of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 68 31 99 B) Armed Police Force 56 13 69 C) Foreign Services 0 0 0 Total in part (A+B+C) 124 44 168 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification Number of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother Roll Draft Roll-2017 124 44 168 II Additions List Supplement 1 Summary revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Supplement 2 Continuous revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Sub Total : 124 44 168 III Deletions List Supplement 1 Summary revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Supplement 2 Continuous revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Sub Total : 0 0 0 Net Electors in the Roll after (I+II-III) 124 44 168 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS : Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 Summary revision of last part of Electoral Roll 1 Supplement 2 Continuous revision of last part of Electoral Roll 0 Total : 1 ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 of Assembly Constituency 37 MANJERI, (S11) KERALA A . -

The Cholas: Some Enduring Issues of Statecraft, Military Matters and International Relations

The Cholas Some Enduring Issues of Statecraft, Military Matters and International Relations P.K. Gautam* The article addresses the deficit in the indigenous, rich historical knowledge of south India. It does this by examining the military and political activities of the Cholas to understand the employment of various supplementary strategies. The article deals with the engagements and battles of the Cholas with other kingdoms of south India, and ‘externally’ with Sri Lanka. It begins with an exposition of various types of alliances that were an integral part of the military strategy of the time. It also seeks to historically contextualize modern diplomatic developments and explains some issues of indigenous historical knowledge of that period that are of relevance even in the twenty-first century: continued phenomenon of changing alliance system in politics; idea of India as a civilization; composition of the army; and the falsehood of the uncontested theory of the Indian defeat syndrome. INTRODUCTION In a diverse subcontinental country such as India, as in other regions of the world such as Europe, China and West and Central Asia, over the millennia, a number of kingdoms and empires have come and gone. What is unchanged, as a part of statecraft, is the formation of alliances to suit interests. * The author is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. He is carrying out research on indigenous historical knowledge in Kautilya’s Arthasastra. He can be contacted at [email protected] ISSN 0976-1004 print © 2013 Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. -

ANNEXURE 10.1 CHAPTER X, PARA 17 ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 State (S11) KERALA No

ANNEXURE 10.1 CHAPTER X, PARA 17 ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 State (S11) KERALA No. Name and Reservation Status of Assembly 53 KONGAD (SC) Last Part : 172 Constituency : No. Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary 8 PALAKAD Service Electors Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located : 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2017 Type of Revision : SPECIAL SUMMARY REVISION Qualifying Date : 01-01-2017 Date of Final Publication : 10-01-2017 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS : 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service Number of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 376 124 500 B) Armed Police Force 5 0 5 C) Foreign Services 0 0 0 Total in part (A+B+C) 381 124 505 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification Number of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother Roll Draft Roll-2017 381 124 505 II Additions List Supplement 1 Summary revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Supplement 2 Continuous revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Sub Total : 381 124 505 III Deletions List Supplement 1 Summary revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Supplement 2 Continuous revision of last part of Electoral 0 0 0 Roll Sub Total : 0 0 0 Net Electors in the Roll after (I+II-III) 381 124 505 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS : Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 Summary revision of last part of Electoral Roll 0 Supplement 2 Continuous revision of last part of Electoral Roll 0 Total : 0 ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 of Assembly Constituency 53 KONGAD (SC), (S11) KERALA A . -

S. No. Rank & Name Service Mahavir Chakra Ic-64405M

S. NO. SERVICE RANK & NAME MAHAVIR CHAKRA 1. IC-64405M COLONEL BIKUMALLA SANTOSH BABU ARMY 16 TH BATTALION THE BIHAR REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) KIRTI CHAKRA 1. JC-413798Y SUBEDAR SANJIV KUMAR ARMY 4TH BATTALION THE PARACHUTE REGIMENT (SPECIAL FORCES) (POSTHUMOUS) 2. SHRI PINTU KUMAR SINGH, INSPECTOR /GD, MHA CRPF (POSTHUMOUS) 3. SHRI SHYAM NARAIN SINGH YADAVA, HEAD MHA CONSTABLE/GD, CRPF (POSTHUMOUS) 4. SHRI VINOD KUMAR, CONSTABLE, CRPF (POSTHUMOUS) MHA 5. SHRI RAHUL MATHUR, DEPUTY COMMANDANT, CRPF MHA VIR CHAKRA 1. JC-561645F NAIB SUBEDAR NUDURAM SOREN ARMY 16 TH BATTALION THE BIHAR REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) 2. 15139118Y HAVILDAR K PALANI ARMY 81 FIELD REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) 3. 15143643M HAVILDAR TEJINDER SINGH ARMY 3 MEDIUM REGIMENT 4. 15439373K NAIK DEEPAK SINGH ARMY THE ARMY MEDICAL CORPS, 16 TH BATTALION THE BIHAR REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) S. NO. SERVICE RANK & NAME 5. 2516683X SEPOY GURTEJ SINGH ARMY 3RD BATTALION THE PUNJAB REGIMENT (POSTHUMOUS) SHAURYA CHAKRA 1. IC-76429H MAJOR ANUJ SOOD ARMY BRIGADE OF THE GUARDS, 21 ST BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES (POSTHUMOUS) 2. G/5022546P RIFLEMAN PRANAB JYOTI DAS ARMY 6TH BATTALION THE ASSAM RIFLES 3. 13631414L PARATROOPER SONAM TSHERING TAMANG ARMY 4TH BATTALION THE PARACHUTE REGIMENT (SPECIAL FORCES) 4. SHRI ARSHAD KHAN, INSPECTOR, J&K MHA POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) 5. SHRI GH MUSTAFA BARAH, SGCT, J&K MHA POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) 6. SHRI NASEER AHMAD KOLIE, SGCT, CONSTABLE, J&K MHA POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) 7. SHRI BILAL AHMAD MAGRAY, SPECIAL POLICE OFFICER, MHA J&K POLICE (POSTHUMOUS) BAR TO SENA MEDAL (GALLANTRY) 1. IC-65402L COLONEL ASHUTOSH SHARMA, BAR TO SENA ARMY MEDAL (POSTHUMOUS) BRIGADE OF THE GUARDS, 21 ST BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES 2. -

No.2593608N Ex.Sepoy Ex Indian Army MRC S.Venkatesan, S/O Late

1 ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, CHENNAI O.A. No.18 of 2017 Monday, the 9th day of July, 2018 THE HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE V.S.RAVI (MEMBER – J ) AND THE HONOURABLE LT GEN C.A.KRISHNAN (MEMBER – A ) No.2593608N Ex.Sepoy Ex Indian Army MRC S.Venkatesan, S/o Late Seenivasan, aged 48 years 10/8, Laxmipuram South Manapparai Tiruchirappalli-621306, Tamil Nadu …Applicant By Legal Practitioner: Shri N.Sundararajan Vs. 1. Union of India, Represented by Secretary Ministry of Defence South Block, New Delhi-110 011 2. The Chief of the Army Staff Integrated Head Quarters Ministry of Defence(Army), New Delhi-110 011. 3. The Officer-in-Charge, Records Madras Regiment Abhilekh Karyalaya C/o 56 APO, PIN 900458 …Respondents By: Shri V.Balasubramanian Central Government Sr. Panel Counsel for Respondents O.A.18 of 2017 2 ORDER HON’BLE LT. GEN. C.A.KRISHNAN, (MEMBER-A) 1. The applicant has filed this Original Application before this Tribunal praying for his reinstatement in the Army in the same cadre as Sepoy with effect from 01.04.2001 with continuity of service with 50% backwages from 01.04.2001, or, in the alternative, payment of Rs.30 lakhs as cost of damages for his sufferings due to the erratic remark in his Discharge Book as Non Ex-serviceman which resulted in non-availability of government benefits to him for the past 15 years as extended to ex-servicemen, and also prayed for the discretionary grant of special pension by the Army, under the Army Pension Rules. 2.