Behavioral Decision-Making: an Application to the Setting of Magazine Subscription Prices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 June 1, 2021 CERTIFIED MAIL – RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED Via Email: Pryan@Commo

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION Washington, DC 20463 June 1, 2021 CERTIFIED MAIL – RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED Via Email: [email protected] Paul S. Ryan Common Cause 805 15th Street, NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 RE: MUR 7324 Dear Mr. Ryan: The Federal Election Commission (“Commission”) has considered the allegations contained in your complaint dated February 20, 2018. The Commission found reason to believe that respondents David J. Pecker and American Media, Inc. knowingly and willfully violated 52 U.S.C. § 30118(a). The Factual and Legal Analysis, which formed a basis for the Commission’s finding, is enclosed for your information. On May 17, 2021, a conciliation agreement signed by A360 Media, LLC, as successor in interest to American Media, Inc. was accepted by the Commission and the Commission closed the file as to Pecker and American Media, Inc. A copy of the conciliation agreement is enclosed for your information. There were an insufficient number of votes to find reason to believe that the remaining respondents violated the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended (the “Act”). Accordingly, on May 20, 2021, the Commission closed the file in MUR 7324. A Statement of Reasons providing a basis for the Commission’s decision will follow. Documents related to the case will be placed on the public record within 30 days. See Disclosure of Certain Documents in Enforcement and Other Matters, 81 Fed. Reg. 50,702 (Aug. 2, 2016), effective September 1, 2016. MUR 7324 Letter to Paul S. Ryan Page 2 The Act allows a complainant to seek judicial review of the Commission’s dismissal of this action. -

This Is “Magazines”, Chapter 5 from the Book Culture and Media (Index.Html) (V

This is “Magazines”, chapter 5 from the book Culture and Media (index.html) (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. i Chapter 5 Magazines Changing Times, Changing Tastes On October 5, 2009, publisher Condé Nast announced that the November 2009 issue of respected food Figure 5.1 magazine Gourmet would be its last. The decision came as a shock to many readers who, since 1941, had believed that “Gourmet was to food what Vogue is to fashion, a magazine with a rich history and a perch high in the publishing firmament.”Stephanie Clifford, “Condé Nast Closes Gourmet and 3 Other Magazines,” New York Times, October 6, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/ 10/06/business/media/06gourmet.html. -

Magazine Subscriptions

Magazine Subscriptions PTP 2707 Princeton Drive Austin, Texas 78741 Local Phone: 512/442-5470 Outside Austin, Call: 1-800-733-5470 Fax: 512/442-5253 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.magazinesptp.com Jessica Cobb Killeen ISD Bid for 16-20-06-207 (Magazine Subscriptions) 7/11/16 Purchasing Dept. Retail Item Percent Net Unit Ter Unit No. Discount Price Subscription Title Iss. m Price 0001 5.0 MUSTANG & SUPER FORDS now Muscle Mustangs & Fast Fords 12 1Yr. $ 44.99 30% $ 31.49 0002 ACOUSTIC GUITAR 12 1Yr. $ 36.95 30% $ 25.87 0003 ACTION COMICS SUPERMAN 12 1Yr. $ 29.99 30% $ 20.99 0004 ACTION PURSUIT GAMES Single issues through the website only 12 1Yr. $ - 0005 AIR & SPACE SMITHSONIAN 6 1Yr. $ 28.00 30% $ 19.60 0006 AIR FORCE TIMES **No discount 52 1Yr. $ 58.00 0% $ 58.00 0007 ALFRED HITCHCOCKS MYSTERY MAGAZINE 12 1Yr. $ 32.00 30% $ 22.40 0008 ALL YOU 2015 Dec: Ceased 12 1Yr. $ - 0009 ALLURE 12 1Yr. $ 15.00 30% $ 10.50 0010 ALTERNATIVE PRESS 12 1Yr. $ 15.00 15% $ 12.75 0011 AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 12 1Yr. $ 64.00 15% $ 54.40 0012 AMERICA (National Catholic Weekly) 39 1Yr. $ 60.95 15% $ 51.81 0013 AMERICAN ANGLER 6 1Yr. $ 19.95 30% $ 13.97 0014 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF **No discount 4 1Yr. $ 95.00 0% $ 95.00 0015 AMERICAN BABY 2015 May: Free Online at americanbaby.com 12 1Yr. $ - 0016 AMERICAN CHEERLEADER 6 1Yr. $ 17.95 30% $ 12.57 0017 AMERICAN COWBOY 6 1Yr. $ 26.60 15% $ 22.61 0018 AMERICAN CRAFT 6 1Yr. -

Flipster Magazines

Flipster Magazines Cricket AARP the Magazine Crochet! Advocate (the) Cruising World AllRecipes Current Biography Allure Curve Alternative Medicine Delight Gluten Free Amateur Gardening Diabetic Self-Management Animal Tales Discover Architectural Digest DIVERSEability Art in America Do It Yourself Artist's Magazine (the) Dogster Ask Dr. Oz: The Good Life Ask Teachers Guide Dwell Astronomy Eating Well Atlantic (the) Entertainment Weekly Audiofile Equus Audobon Faces BabyBug Faces Teachers Guide Baseball Digest FIDO Friendly Bazoof Fine Cooking BBC Easy Cook Fine Gardening BBC Good Food Magazine First for Women Beadwork Food Network Magazine Birds and Blooms Food + Wine Bloomberg Businessweek Foreward Reviews Bon Appetit Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide Book Links Girlfriend Booklist Golf Magazine BuddhaDharma Good Housekeeping Catster GQ Chess Life Harvard Health Letter Chess Life for Kids Harvard Women's Health Watch Chickadee Health Chirp High Five Bilingue Christianity Today Highlights Cinema Scope Highlights High Five Clean Eating History Magazine Click Horn Book Magazine COINage In Touch Weekly Commonweal Information Today Computers in Libraries Inked Craft Beer and Brewing InStyle J-14 LadyBug Sailing World LadyBug Teachers Guide School Library Journal Library Journal Simply Gluten Free Lion's Roar Soccer 360 Martha Stewart Living Spider Men's Journal Spider Teachers Guide Mindful Spirituality & Health Modern Cat Sports Illustrated Modern Dog Sports Illustrated Kids Muse Taste of Home Muse Teachers Guide Teen Graffiti Magazine National -

Slayage, Numbers 13/14

Giada Da Ros When, Where, and How Much is Buffy a Soap Opera? Translated from the Italian and with the editorial assistance of Rhonda Wilcox. Spike: Passions is on! Timmy's down the bloody well, and if you make me miss it I'll — Giles: Do what? Lick me to death? (Something Blue, 4009) Joyce: I-I love what you've, um... neglected to do with the place. Spike: Just don't break anything. And don't make a lotta noise. Passions is coming on. Joyce: Passions? Oh, do you think Timmy's really dead? Spike: Oh, no, no. She can just sew him back together. He's a doll, for God's sake. Joyce: Ah, what about the wedding? I mean, there's no way they're gonna go through with that. (Checkpoint, 5012) Tabitha (talking to Timmy): When will you get it through your fat head? Charity is the enemy. Buffy the Vampire Slayer is the enemy. The busybodies that call themselves the Others are the enemy! One of these days Buffy and the others will be wiped off the face of the earth, but until that time, we don’t want to make our friend in the basement mad, do we? (Passions) Stephen/Caleb: And your job is? Rafe: Vampire slayer. (Port Charles – Naked Eyes) BUFFY AS A SOAP (1) Very often, Buffy the Vampire Slayer is referred to as a soap opera. There are many occasions when it has been defined as such, or at least linked to the genre of daytime dramas. This perception is shared by at least three types of viewers. -

Alternate Archives in US Daytime TV Soap Opera Historiography

Elana Levine Alternate Archives in US Daytime TV Soap Opera Historiography Television history is more dependent on alternative archives than is film his- tory. A range of factors place TV outside the parameters of conventional archi- val practice. The live broadcast of television in its early years and the ongoing liveness of some forms of TV have posed a technological challenge to the institutionalized archiving of programs, as have changing formats of videotape and the disintegration of tape itself. The domestic reception of TV, along with its commercial funding structure in many parts of the world, has also ranked television low in cultural hierarchies, and thereby low in priorities of preser- vation. The dismissal of most television for much of its history as inartistic, or as pandering to a “lowest common denominator,” has led many to devalue TV programs as historical artifacts and as objects of critical analysis. One of the clearest cases of this conventional archival neglect is the US daytime television soap opera. Soap operas transitioned to US television from radio in the early 1950s, broadcast daily episodes live into the early 1960s, and were subsequently shot on (sequential formats of) videotape. To many, the soap opera epitomizes the characterization of television as com- mercial, domestic, and unartful. As a result, few involved in the production, distribution, or preservation of television have found soap opera to be an object worthy of or viable for preservation. This situation is compounded by the voluminousness of soap opera texts— many daytime serials air daily for decades— as well as soaps’ associations with women and other marginal- ized audiences such as children, the elderly, and the unemployed, who are assumed to be home during the day with “nothing better to do.” The histo- riography of the soap opera may seem impossible given these constraints. -

Anthrax Scare Shuts Down National Enquirer

HOT TOPICS: Bost on Marat hon • Pre ssure Cooke r Bomb • Myst e ry Man On Roof Search Ho me U.S. Wo rld Po lit ics Video Invest igat ive Healt h Ent ert ainment Mo ney Tech Travel WATCH LIVE: Funeral for Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher HOME > ENTERTAINMENT reriuqEn lanoiNtaDw on stuSh eraSc xarhtAn Oct. 9 In a story that seems ripped from its own outrageous tabloid headlines, The National Enquirer has closed its Boca Raton, Fla., headquarters Monday after Share health department officials detected the anthrax bacterium on its premises. 1 0 Last week, 63-year-old Robert Stevens, a photo editor for the company, died from anthrax. Officials thought it to be an isolated case, but then began testing Like Stevens' family and associates. This weekend, a co-worker of Stevens tested positive for exposure to the extremely rare, yet potentially deadly disease. 0 0 Immediately following the second case, staffers were told to stay out of the PDFmyURL.com Sharre building until further notice. According to Entertainment Tonight, the tabloid's Share employees are undergoing nasal passage testing Monday at a local clinic. "Obviously, our first concern is the health and well-being of our employees Email and their families," said Michael Kahane, Vice President and General Counsel Comment of American Media Inc., which publishes The National Enquirer and other Print supermarket tabloids, told ET. Text Siz e - / + FBI is Investigating While officials stress there is no indication the discovery of anthrax in South Florida is linked to any terrorist activity, the FBI has assumed the lead in the investigation, with the cooperation of law enforcement, local and state health workers, and Center for Disease Control officials, according to ABCNEWS.com. -

Stanton Rounds up New Food and Lifestyle Center, Rodeo 39

SUNDAY,OCTOBER 11,2020 /// Times Community News publication serving Orange County /// timesoc.com Voters assured fraud won’t be tolerated At a news conference, county officials maintain ballots will be protected and intimidation will not be allowed. BY BEN BRAZIL Following President Trump’s repeated — and disproven — statements about widespread election fraud, Orange County officials sought to assure voters Monday that they would defend ballot integrity and protect polling places from outside inter- ference. “I think one of the messages that I want to make clear is that we’re not going to tolerate intim- idation, we’re not going to toler- Photos courtesy of Rodeo 39 ate rule-breaking in the vote cen- RODEO 39, a new dining and lifestyle center in Stanton, is set to open Saturday. It is the creation of San Juan Capistrano developer Dan Almquist. ters, and we want to make sure that the laws, the regulations and the rules are followed,” Orange County Registrar Neal Kelley said at a news conference outside the Stanton rounds up new food Santa Ana office. During the event, crews loaded semi-trucks with 1.7million bal- lots set to be mailed this week to and lifestyle center, Rodeo 39 registered voters. Trump has urged supporters to monitor voting centers for fraud, BY LORI BASHEDA adirective that has led to con- cerns nationwide about the po- Mention that you’re headed to Stanton and tential for intimidation and dis- you’re likely to hear something along the ruption. lines of: Where’s Stanton? Trump has repeated the widely But a new public market is putting the tiny discredited claim that mail-in city on Orange County’s map in a big way. -

Tabloidization in the Modern American Press: a Textual Analysis and Assessment of Newspaper and Tabloid Coverage of the “Runaway Bride” Case

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication 1-12-2006 Tabloidization in the Modern American Press: A Textual Analysis and Assessment of Newspaper and Tabloid Coverage of the “Runaway Bride” Case Nichola Reneé Harris Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Nichola Reneé, "Tabloidization in the Modern American Press: A Textual Analysis and Assessment of Newspaper and Tabloid Coverage of the “Runaway Bride” Case." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tabloidization in the Modern American Press: A Textual Analysis and Assessment of Newspaper and Tabloid Coverage of the “Runaway Bride” Case by Nichola Reneé Harris Under the Direction of Merrill Morris ABSTRACT The media have extensive power in that they represent the primary, and often the only, source of information about many important events and topics. Media can define which events are important, as well as how media consumers should understand these events. The current trend towards tabloidization, or sensationalism, in today’s American -

Sexy Sensationalism Case Study: the Af Scination with Celebrity News and Why USA Today Caters to the Obsession Grant Edward Boxleitner University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-6-2007 Sexy Sensationalism Case Study: The aF scination with Celebrity News and Why USA Today Caters to the Obsession Grant Edward Boxleitner University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Boxleitner, Grant Edward, "Sexy Sensationalism Case Study: The asF cination with Celebrity News and Why USA Today Caters to the Obsession" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/642 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexy Sensationalism Case Study: The Fascination with Celebrity News and Why USA Today Caters to the Obsession by Grant Edward Boxleitner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Mass Communications College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Robert Dardenne, Ph.D. Gary Mormino, Ph.D Mike Killenberg, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 6, 2007 Keywords: gossip, media, ethics, newspapers, competition © Copyright 2007, Grant Edward Boxleitner Table of Contents Abstract.............................................................................................................................. -

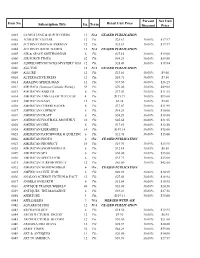

Item No. Subscription Title Iss. Term Retail Unit Price Percent Discount Net Unit Price

Percent Net Unit Item No. Retail Unit Price Subscription Title Iss. Term Discount Price 0001 5.0 MUSTANG & SUPER FORDS 12 N/A CEASED PUBLICATION 0002 ACOUSTIC GUITAR 12 1Yr. $25.67 30.00% $17.97 0003 ACTION COMICS SUPERMAN 12 1Yr. $25.67 30.00% $17.97 0004 ACTION PURSUIT GAMES 12 N/A CEASED PUBLICATION 0005 AIR & SPACE SMITHSONIAN 6 1Yr. $27.14 30.00% $19.00 0006 AIR FORCE TIMES 52 1Yr. $84.29 30.00% $59.00 0007 ALFRED HITCHCOCKS MYSTERY MAG 12 1Yr. $28.49 30.00% $19.94 0008 ALL YOU 12 N/A CEASED PUBLICATION 0009 ALLURE 12 1Yr. $12.86 30.00% $9.00 0010 ALTERNATIVE PRESS 12 1Yr. $10.71 30.00% $7.50 0011 AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 12 1Yr. $37.50 30.00% $26.25 0012 AMERICA (National Catholic Weekly) 39 1Yr. $70.00 30.00% $49.00 0013 AMERICAN ANGLER 6 1Yr. $17.07 30.00% $11.95 0014 AMERICAN ANNALS OF THE DEAF 4 1Yr. $135.71 30.00% $95.00 0015 AMERICAN BABY 12 1Yr. $7.14 30.00% $5.00 0016 AMERICAN CHEERLEADER 6 1Yr. $17.07 30.00% $11.95 0017 AMERICAN COWBOY 6 1Yr. $14.29 30.00% $10.00 0018 AMERICAN CRAFT 6 1Yr. $54.29 30.00% $38.00 0019 AMERICAN FOOTBALL MONTHLY 10 1Yr. $45.64 30.00% $31.95 0020 AMERICAN GIRL 6 1Yr. $17.86 30.00% $12.50 0024 AMERICAN LIBRARIES 10 1Yr. $107.14 30.00% $75.00 0025 AMERICAN PATCHWORK & QUILTING 6 1Yr. $21.43 30.00% $15.00 0026 AMERICAN PHOTO 6 1Yr. -

Just Country: a Magazine Prototype and Business Plan

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Fall 4-14-2021 Just Country: A Magazine Prototype and Business Plan Clare Wojciechowski Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wojciechowski, Clare, "Just Country: A Magazine Prototype and Business Plan" (2021). Honors Theses. 1626. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1626 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUST COUNTRY: A MAGAZINE PROTOTYPE AND BUSINESS PLAN by Clare Wojciechowski A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, MS May 2021 Approved By ______________________________ Advisor: Doctor Samir Husni ______________________________ Reader: Doctor Jason Cain ______________________________ Reader: Professor Evangeline Ivy © 2021 Clare Wojciechowski ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents, without whom I would not be where I am today. Their unending support and love has guided me throughout my life and encouraged me to pursue all my dreams and passions. The idea for this thesis stemmed from two of my deepest loves; music and journalism. I owe both of these interests to my parents; my dad, who took me to my very first concert, and my mom, who has had a subscription to People magaZine for as long as I can remember.