Hunter X Hunter's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"ALL OUT!!" Is the First Ever Animated TV Show About Rugby! to Be Produced by TMS and MADHOUSE! Broadcast Will Begin I

N E W S R E L E A S E April 4th, 2016 TMS Entertainment Co., Ltd. "ALL OUT!!" is the first ever animated TV show about rugby! To be produced by TMS and MADHOUSE! Broadcast will begin in the fall of 2016 A team assembled from the sports production elite! A portrayal of the fire of youth! TMS Entertainment Co., Ltd. (Head office: Nakano-ku, Tokyo, President: Yoshiharu Suzuki, referred to below as TMS), will produce an animated TV series based on "ALL OUT!!", the authentic high school rugby manga created by Shiori Amase (currently serialized in Kodansha's 'Morning Two'). They will make the announcement of the broadcast beginning in the fall of 2016, and release teaser visuals. [Official TV show website] http://allout-anime.com/ [Official Twitter account] https://twitter.com/allout_anime [Official Facebook page] https://www.facebook.com/allout.animation ■ About ALL OUT!! "ALL OUT!!" is a high school rugby comic loved for its dynamic production and sensitive psychological portrayal. It has been serialized in the monthly "Morning Two" since 2012, and the comic has now been published up to Volume 7 (referred to below as "ongoing publication".) Volume 8 is scheduled for publication on February 23rd, with the simultaneous release of a Special Edition Volume 8 bundled with an original drama CD featuring the same cast as the animated TV show, as well as a Special Edition Volume 1 consisting of the previously published Volume 1 bundled with the original drama CD. ■ A stellar team has been assembled! The show is directed by Kenichi Shimizu, who has worked on "Parasyte -The Maxim-", "Avengers Confidential: Black Widow & Punisher", etc., and is widely active both in Japan and overseas. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Protoculture Addicts #68

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF NEWS ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan / North America ............................................................... 5, 10 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager ANIME & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................. 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES ............................................................................................................ 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 11 Contributing Editors Aaron K. Dawe, Asaka Dawe, Keith Dawe REVIEWS Kevin Lillard, James S. Taylor MODELS: ....................................................................................................................... 33, 39 MANGA: ............................................................................................................................. 40 Layout FESTIVAL: Fantasia 2001 (Anime, Part 2) The Safe House Metropolis ...................................................................................................................... 42 Cover Millenium Actress ........................................................................................................... -

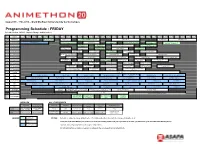

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

Animagazin 1. Sz. (2021. Január 20.)

Téli szezon 2021 Összeállította: Hirotaka Anime szezon 019 2.43: Seiin Koukou Danshi Volley-bu Back Arrow Ex-Arm regény alapján original manga alapján Stúdió: Stúdió: Stúdió: David Production Studio VOLN Visual Flight Műfaj: Műfaj: Műfaj: iskola, sport akció, fantasy, mecha akció, sci-fi, seinen Seiyuuk: Seiyuuk: Seiyuuk: Umehara Yuuichirou, Ono Kenshou, Ozawa Ari, Kitou Akari, Komatsu Mikako Ono Kenshou, Aou Shouta Kaji Yuki Leírás Ajánló Leírás Ajánló Leírás Ajánló Haijima Kimichika röp- Röplabdás anime, Ringarindo területét Egy új mecha sorozat, Natsume Akira egy Már kétszer elhalasz- labdajátékos, visszaköltözik ami nem a Haikyuu. De fal veszi körül, védi és óvja rég láttunk ilyet, a műfaj középsulis diák, akinek csak tott címről van szó, talán Fukuiba, ahol a gyerekkorát hát ki mondta, hogy nem az ott élőket. A fal az isten, rajongói mostanában kicsit az agyát sikerült megmen- most elindul. Nekem hir- töltötte. Itt újra találkozik üthet más a labdába az is- és Ringarindo alapja. el vannak hanyagolva, szó- teni egy tragikus közleke- telen Robotzsaru érzetem egykori barátjával, Kuroba mert cím mellett. Egy re- Egy nap, egy rejtélyes val ez most jól jön. A Studio dési baleset után. Most az lett tőle. Főleg akcióköz- Yunival, akivel egy régi ve- gényadaptációról van szó, férfi, aki Back Arrownak ne- VOLN (Ushio to Tora, Kara- EX-ARM különleges rendőri pontú animének néz ki, sok szekedés miatt romlott meg ami 2015 óta fut. A David vezi magát megjelenik Essha kuri Circus (AniMagazin 50.)) egységgel működik együtt, harccal. Egy 2015-2019 kö- a viszonya. Elkezdik a Seiin Productionról csak annyit faluban. Arrow elvesztette a fogja készíteni, akik eddigi hogy visszaszerezze elve- zött készült mangát adap- középiskolát és csatlakoz- mondok, hogy JoJo és Ha- memóriáját, csak egy dolog- szerény felhozataluk elle- szett emlékeit és testét. -

Manga: Japan's Favorite Entertainment Media

Japanese Culture Now http://www.tjf.or.jp/takarabako/ Japanese pop culture, in the form of anime, manga, Manga: and computer games, has increasingly attracted at- tention worldwide over the last several years. Not just a small number of enthusiasts but people in Japan’s Favorite general have begun to appreciate the enjoyment and sophistication of Japanese pop culture. This installment of “Japanese Culture Now” features Entertainment Media manga, Japanese comics. Characteristics of Japanese Comics Chronology of Postwar 1) The mainstream is story manga Japanese Manga The mainstream of manga in Japan today is “story manga” that have clear narrative storylines and pictures dividing the pages into 1940s ❖ Manga for rent at kashihon’ya (small-scale book-lending shops) frames containing dialogue, onomatopoeia “sound” effects, and win popularity ❖ Publication of Shin Takarajima [New Treasure Island] by other text. Reading through the frames, the reader experiences the Tezuka Osamu, birth of full-fledged story manga (1947) sense of watching a movie. 2) Not limited to children 1950s ❖ Monthly manga magazines published ❖ Inauguration of weekly manga magazines, Shukan shonen sande Manga magazines published in Japan generally target certain age and Shukan shonen magajin (1959) or other groups, as in the case of boys’ or girls’ manga magazines (shonen/shojo manga zasshi), which are read mainly by elementary 1960s ❖ Spread of manga reading to university students ❖ Popularity of “supo-kon manga” featuring sports (supotsu) and and junior high school students, -

Released 20Th December 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS

Released 20th December 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS OCT170039 ANGEL SEASON 11 #12 OCT170040 ANGEL SEASON 11 #12 VAR AUG170013 BLACK HAMMER TP VOL 02 THE EVENT OCT170019 EMPOWERED & SISTAH SPOOKYS HIGH SCHOOL HELL #1 OCT170021 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 OCT170023 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 HUGHES SKETCH VAR OCT170022 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 MIGNOLA VAR OCT170020 JOE GOLEM OCCULT DET FLESH & BLOOD #1 (OF 2) OCT170061 SHERLOCK FRANKENSTEIN & LEGION OF EVIL #3 (OF 4) OCT170062 SHERLOCK FRANKENSTEIN & LEGION OF EVIL #3 (OF 4) FEGREDO VAR OCT170080 TOMB RAIDER SURVIVORS CRUSADE #2 (OF 4) APR170127 WITCHER 3 WILD HUNT FIGURE GERALT URSINE GRANDMASTER DC COMICS OCT170220 AQUAMAN #31 OCT170221 AQUAMAN #31 VAR ED JUL170469 BATGIRL THE BRONZE AGE OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 OCT170227 BATMAN #37 OCT170228 BATMAN #37 VAR ED SEP170410 BATMAN ARKHAM JOKERS DAUGHTER TP SEP170399 BATMAN DETECTIVE TP VOL 04 DEUS EX MACHINA (REBIRTH) OCT170213 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES II #2 (OF 6) OCT170214 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES II #2 (OF 6) VAR ED OCT170233 BATWOMAN #10 OCT170234 BATWOMAN #10 VAR ED OCT170242 BOMBSHELLS UNITED #8 SEP170248 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) SEP170251 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) DANIEL VAR ED SEP170249 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) KUBERT VAR ED SEP170250 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) LEE VAR ED SEP170444 EVERAFTER TP VOL 02 UNSENTIMENTAL EDUCATION OCT170335 FUTURE QUEST PRESENTS #5 OCT170336 FUTURE QUEST PRESENTS #5 VAR ED OCT170263 GREEN LANTERNS #37 OCT170264 GREEN LANTERNS #37 VAR ED SEP170404 GREEN LANTERNS TP VOL 04 THE FIRST RINGS (REBIRTH) -

History 146C: a History of Manga Fall 2019; Monday and Wednesday 12:00-1:15; Brighton Hall 214

History 146C: A History of Manga Fall 2019; Monday and Wednesday 12:00-1:15; Brighton Hall 214 Insufficient Direction, by Moyoco Anno This syllabus is subject to change at any time. Changes will be clearly explained in class, but it is the student’s responsibility to stay abreast of the changes. General Information Prof. Jeffrey Dym http://www.csus.edu/faculty/d/dym/ Office: Tahoe 3088 e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays 1:30-3:00, Tuesdays & Thursdays 10:30-11:30, and by appointment Catalog Description HIST 146C: A survey of the history of manga (Japanese graphic novels) that will trace the historical antecedents of manga from ancient Japan to today. The course will focus on major artists, genres, and works of manga produced in Japan and translated into English. 3 units. GE Area: C-2 1 Course Description Manga is one of the most important art forms to emerge from Japan. Its importance as a medium of visual culture and storytelling cannot be denied. The aim of this course is to introduce students and to expose students to as much of the history and breadth of manga as possible. The breadth and scope of manga is limitless, as every imaginable genre exists. With over 10,000 manga being published every year (roughly one third of all published material in Japan), there is no way that one course can cover the complete history of manga, but we will cover as much as possible. We will read a number of manga together as a class and discuss them.