Photographic Gestures and Situated Belongings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Portfolio

PHOTO LONDON ANNOUNCES 2019 TALKS PROGRAMME Photo London has announced details of the Talks Programme for the fifth edition of the Fair, which will take place from 15 - 19 May 2019 at Somerset House. The Programme will showcase the rich and diverse history of photography up until the present day, and explore the current and future direction of the medium in a dynamic format. It will feature talks, debates and discussions with some of the world’s most important and innovative photographers, artists, curators, critics and authors. As well as featuring many celebrated practitioners including Erwin Olaf, Susan Meiselas, Ralph Gibson, Hannah Starkey, Tim Walker, Maja Daniels, Ed Templeton and Vanessa Winship, the Talks Programme includes: • The Photo London Master of Photography 2019 Stephen Shore in conversation with curator David Campany • Martin Parr discusses British identity in his work with historian and broadcaster Dominic Sandbrook • The acclaimed biographer Ann Marks in conversation with the author Anna Sparham on the legacy of Vivian Maier • Gavin Turk discusses his Photo London project Portrait of an Egg with Matthew Collings • Zackary Drucker discusses her work on transgender identities in photography with Chris Boot, Executive Director of Aperture Foundation • Contemporary portrait photographer Martin Schoeller in conversation with publisher Gerhard Steidl • Liz Johnson Artur in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist • Photographer, electronic music producer and DJ, Eamonn Doyle discusses his special Photo London installation Made in Dublin with collaborators David Donohoe and Niall Sweeney • Panel discussions on subjects such as representations of the body; collecting photography; the future of photography curation and the legacy of the pioneering early photographer Roger Fenton • Tickets on sale now at photolondon.org/tickets – Fair tickets are not required to attend talks The Photo London Talks Programme is curated by William A. -

Catalogo-FN15.Pdf

El talento de un momento congelado en el tiempo Cada fotografía es como una pequeña ventana por la que podemos asomarnos a un instante atrapado en el tiempo. Una imagen congelada para siempre, que a veces puede tener la carga expresiva de mil palabras. Nuestra vida está marcada por ellas. Nuestra vida íntima, porque nuestra memoria siguen siendo los álbumes de la infancia, de los estudios, de los veranos, de la familia... Y nuestra vida pública en cuyos recuerdos flotan imágenes de aviones chocando contra rascacielos o de un tricornio en la tribuna del Congreso. Dicen que la vida no es una fotografía, sino una película. Y tal vez tienen razón. Pero en el sentido de que una película son cientos de miles de fotografías. La diferencia entre el arte y la simple foto es, precisamente, la capacidad de quién es capaz de conseguir realizar todo un relato en una sola imagen; una película en un fotograma. Nuestra vida está marcada por esas instantáneas que son un grito mudo, una pincelada genial, una denuncia, un soplo de ternura, de amor, de rabia... Existen fotos periodísticas que sacuden las conciencias de la gente mucho más que los discursos políticos y las acciones de los Gobiernos. El cadáver de un niño tendido sobre la arena de una playa en un Mediterráneo de los horrores se aferró a las conciencias de media Europa como una garra de hielo. Hay fotos que mezclan formas y colores para despertar en el espectador una sinfonía de armonías. Existen fotos que captan la naturaleza profunda de una época, de un personaje, de un acontecimiento. -

Vanessa Winship

VANESSA WINSHIP 30th MAY – 31st AUGUST 2014 Untitled, from the series she dances on Jackson. United States, 2011-2012 © Vanessa Winship Press conference: May 28th, 2013 Dates: May 30th – August 31th Venue: FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE. Bárbara de Braganza,13, Madrid, Spain Curator: Carlos Martín García Production: Exhibition organised by FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE Website: http://www.exposicionesmapfrearte.com/winship Facebook www.facebook.com/fundacionmapfrecultura Twitter https://twitter.com/mapfreFcultura FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE opens a new exhibition hall in the heart of the city, alongside Madrid's main cultural institutions. Located at Calle Bárbara de Braganza 13 (on the corner of Paseo de Recoletos), opposite the National Library, the space boasts 868 square meters spread over two floors and will provide us with a city-center venue in which to host the photography exhibitions we have been organizing for several years. In 2007 FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE decided to make photography a key theme of its arts program and acquired the complete Brown Sisters series by Nicholas Nixon, marking the beginning of an incipient photography collection. This acquisition also lay the foundations for a new focus in our exhibition program, launched at our Azca gallery in January 2009, based simultaneously on the work of the grand masters and on contemporary photographers who had earned international acclaim but had never held a major retrospective of their work. Walker Evans was the subject of our first exhibition, and he has been followed by Fazal Sheikh, Graciela Iturbide, Lisette Model and others. All in all, we have hosted 18 exhibitions since that first experience, making us the only institution in Madrid that offers a regular program of four photography exhibitions a year. -

Visual Arts Board Report 2018 Public Report Of

Committee(s): Date(s): Barbican Centre Board 18 July 2018 Subject: Visual Arts Board Report 2018 Public Report of: Artistic Director For Discussion Report Author: Jane Alison, Head of Visual Arts Summary This report provides an overview of the Visual Art department's strategy and planning, in the context of the Barbican's vision and mission and Strategic Business Plans. It is divided into the following sections: 1. Mission Statement and Strategic Objectives 2. Challenges and Opportunities 3. Exhibition Round-up 4. Income Generation 5. Equality and Inclusion 6. Future Plans (non-public) 7. Conclusion and Questions (non-public) Appendix 1: Financial and attendance analysis Appendix 2: Ticket sales reports Recommendation Members are asked to note the report. 1. MISSION STATEMENT AND STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES MISSION STATEMENT Barbican’s visual arts programme embraces art, architecture, design and photography. Many of our Art Gallery exhibitions explore the interconnections between disciplines, periods and cultures, and aim to imagine the world in new ways. Designers, artists and architects are our collaborators in this process. We are increasingly engaged in exploring the links between performance, dance and the visuals arts, as well as between art, architecture and design. We invest in the artists of today and tomorrow; the Curve gallery is one of the few galleries in London devoted to the commissioning of new work by contemporary artists. Additionally, we work directly with leading and emergent architects and designers on all our exhibitions. Through our activities we aim to inspire more people to discover and love the arts. Entrance to the Curve is free. Through Young Barbican we offer £5 tickets to 14-25 year olds for our paid exhibitions, children under 14 are free. -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

Artist Questionnaire: Sophie Gerrard IG

Artist Questionnaire: Sophie Gerrard IG: Which artists/photographers do you particularly respect? I’m constantly finding new projects and photographers and artists and painters and books which inspire me and which I respect. Some long standing favourites have been Joel Sternfeld, Pieter Hugo, Edward Burtynski, Tim Hetherington and Richard Misrach. I’m also influenced by painters, particularly Lucian Freud, and some of the Dutch landscape painters. IG: Why do you choose photography as your artistic medium? I believe quite passionately in the power of photography to communicate important stories and information visually. Photography can be used as a powerful tool and has an almost unique ability to act as a universal language. I began my career in environmental sciences, after travelling in SE Asia and becoming aware of the work of important photojournalists like Don McCullin, I turned to photography in order to combine my passion for visual arts and creativity with the ability to communicate important environmental stories. I saw, and still see, photography as a tool that allows me to do that. For me, the stories I tell are nearly always about the people. Environmental issues are my passion, but it’s the people behind these stories and in this case, these landscapes, who I am interested it. Photography gives me a wonderful excuse to explore, to meet people, to learn and to look closely, to dig under the surface in order to find what’s underneath, and that is an important process for me. Long term documentary projects give me the opportunity to spend time with people, know them and learn their stories. -

7.10 Nov 2019 Grand Palais

PRESS KIT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST, YANCEY RICHARDSON, NEW YORK, AND STEVENSON CAPE TOWN/JOHANNESBURG CAPE AND STEVENSON NEW YORK, RICHARDSON, YANCEY OF THE ARTIST, COURTESY © ZANELE MUHOLI. © ZANELE 7.10 NOV 2019 GRAND PALAIS Official Partners With the patronage of the Ministry of Culture Under the High Patronage of Mr Emmanuel MACRON President of the French Republic [email protected] - London: Katie Campbell +44 (0) 7392 871272 - Paris: Pierre-Édouard MOUTIN +33 (0)6 26 25 51 57 Marina DAVID +33 (0)6 86 72 24 21 Andréa AZÉMA +33 (0)7 76 80 75 03 Reed Expositions France 52-54 quai de Dion-Bouton 92806 Puteaux cedex [email protected] / www.parisphoto.com - Tel. +33 (0)1 47 56 64 69 www.parisphoto.com Press information of images available to the press are regularly updated at press.parisphoto.com Press kit – Paris Photo 2019 – 31.10.2019 INTRODUCTION - FAIR DIRECTORS FLORENCE BOURGEOIS, DIRECTOR CHRISTOPH WIESNER, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR - OFFICIAL FAIR IMAGE EXHIBITORS - GALERIES (SECTORS PRINCIPAL/PRISMES/CURIOSA/FILM) - PUBLISHERS/ART BOOK DEALERS (BOOK SECTOR) - KEY FIGURES EXHIBITOR PROJECTS - PRINCIPAL SECTOR - SOLO & DUO SHOWS - GROUP SHOWS - PRISMES SECTOR - CURIOSA SECTOR - FILM SECTEUR - BOOK SECTOR : BOOK SIGNING PROGRAM PUBLIC PROGRAMMING – EXHIBITIONS / AWARDS FONDATION A STICHTING – BRUSSELS – PRIVATE COLLECTION EXHIBITION PARIS PHOTO – APERTURE FOUNDATION PHOTOBOOKS AWARDS CARTE BLANCHE STUDENTS 2019 – A PLATFORM FOR EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHY IN EUROPE ROBERT FRANK TRIBUTE JPMORGAN CHASE ART COLLECTION - COLLECTIVE IDENTITY -

Chicote Yolanda Hermida

FOTO DNG www.fotodng.com Número 105 - Año X. Mayo 2015 ISSN 1887-3685 9 771887 368002 Alberto CHICOTE Retrato de Autor por Pepe Castro YOLANDA HERMIDA SWIMMING POOL DELIGHT Por César Valdés PROFOTO OFF CAMERA FLASH FOTO DNG Número 105 (Año X - Mayo 2015) INDICE 3 REDACCIÓN 116 MOCHILA VANGUARD ADAPTOR 46 4 NOVEDADES 122 I ENCUENTRO 66 ENTREVISTA A PEPE CASTRO FOTOGRÁFICO IBÉRICO E.F.I. 75 YOLANDA HERMIDA Street Soul Photography 86 SWIMMING POOL DELIGHT 128 NOTICIAS EVENTOS Por César Valdés 190 LIBROS DEL MES 98 MIENTRAS MÁS LEJOS MÁS CERCA, MIENTRAS MÁS CERCA 194 LAS FOTOS DEL MES DE MÁS LEJOS BLIPOINT Por Nelson Martin 104 PROFOTO OFF CAMERA 196 GRUPO FOTO DNG EN FLASH FLICKR Revista Foto DNG Colaboraron en este número: ISSN 1887-3685 www.fotodng.com Jon Harsem, Pepe Castro, Dirección y Editorial: Yolanda Hermida, César Valdés, Ainara Cantón, Déborah Carlos Longarela Zoombie, Nelson Martin, Jose [email protected] Luis Gea, Pedro Diaz Molins, Miguel Rabasco Martínez, Jose Portada: Gálvez Pujol, Fidalgo Pedrosa. Modelo: Alberto Chicote www.albertochicote.com Fotografía: Pepe Castro www.pepecastro.com * Las opiniones, comentarios y notas, son responsabilidad exclusiva de los firmantes o de las entidades que facilitaron los datos para los mismos. La reproducción de artículos, fotografías y dibujos, está prohibida salvo autorización expresa por escrito de sus respectivos autores (excepto aquellos licenciados bajo Creative Commons, que se regirán por la licencia correspondiente). Redacción na vez más nos encontramos cuando estrenamos el mes de mayo y se empieza a vislumbrar el buen tiempo, en esta ocasión os presentamos este número 105 Ucon una portada de Alberto Chicote, todo un lujo tenerlo en nuestra portada al igual que al autor del retrato, Pepe Castro, pero para los que aún no lo conozcáis, os podéis acercar un poquito más a su fotografía con la entrevista que abre este número. -

Committee Report Template

Committee: Date(s): Barbican Board 24 July 2019 Subject: Public Barbican Visual Arts Annual Report Report of: For Information Louise Jeffreys, Artistic Director Report author: Jane Alison, Head of Visual Arts Summary This report provides an overview of the Visual Arts department’s current areas of activity and strategic focus. It outlines the impact of our activity over the past year, and points to key future strategic projects. The report is structured as follows: 1. Introduction Progress on Strategic Change Objectives 2. Gender balance in 2018-19 financial year and into the future 3. Diversity in the 2018-19 exhibition programme 4. Multi-disciplinarity in the 2018-19 programme 5. Workforce of the future: diversification initiatives Public and Critical Successes in the Past Year 6. Critical successes in past year 7. Conclusion Recommendation Members are asked to: • Note the report. Main Report 1. Introduction Barbican Visual Arts is committed to supporting the Barbican Centre’s strategic ‘change’ objectives, as well as playing a meaningful role in contributing to the Corporation of London’s wider objectives. It is especially pertinent that the Gallery’s exhibitions and artist commissions encourage a flourishing society and thriving economy. We believe that access to the best visual art and design is inspirational and enriching. Given the high profile of the Barbican’s visual arts programme in the national and international Press, and the number of people who attend our shows, we play a significant role in promoting the Centre, the City and its values, while crucially attracting a sizeable day-time audience, thereby supporting a vibrant atmosphere and supporting income generation from the shop and catering operations at the Barbican. -

Inventario Completo

10 x 10 Japanese photobooks 10 x 10 photobooks. Clap Contepomprary latin 10 x 10 photobooks. American photobooks 2013 Provoke between protest and performance, photography in 2016 From here on [exposición] 2013 Brassaï 1987 At war 2004 Omar Victor Diop: photographe 2013 Mikhael Subotzky: photographe 2007 William Klein: photographe, cinéaste, peintre 2010 On Daido: an homage by photographers & writers 2015 Cuaderno de ejercicios para poetas visuales: el camino de jugar 2013 La colonie des enfants d'izieu 1943-1944 2012 My life is a man 2015 Photographs Vol. 1 2012 Photographs Vol. 2 2014 Photographs Vol. 3 2016 A history of photography: from 1839 to the present 2005 Resultados electorales en Torrejón de Ardoz en las elecciones Cartographie de la photographie contemporaine No. 0 2016 8 japanese photographers another language 2015 Aa Bronson, Mel Bochner, Inaki Working drawing and other visible things on paper not 2008 Aaron Mc Elroy Zine Collection N°25: No time 2015 Aaron McEl Roy, Yokota, Nocturnes . am. project 2012 Aaron Schuman Folk 2016 Aaron Schuman, Isabelle Evertse The document 2016 Aaron Stern I Woke up in my clothes 2013 Ad van Denderen Go no go 2003 Ad van Denderen Steidlmack So blue so blue : edges of the mediterranean 2008 Adam Broomberg / Oliver Scarti 2013 Adam Broomberg / Oliver 2 war primer 2018 Adam Broomberg Oliver DODO 2015 Adam Broomberg, Oliver Fig. 2007 Adam Broomberg; Oliver Humans and other animals 2015 Adam Broomberg; Oliver Holy Bible Adam Panczuk Karczeby 2013 Adina Ionescu Muscel Getting the extra beating heart -

Rassegna Stampa N.12-2014

GRUPPO FOTOGRAFICO ANTENORE, BFi RASSEGNA STAMPA Anno 7o- n.12, Dicembre 2014 Sommario: La fotografia di Nicolàs Muller………………………………………………………………………………pag. 2 Le grandi fotografie di LIFE.…………………………………………………………………………………pag. 3 World Press Photo…………………………………………………………………………………………………pag. 4 Mobile Art: nuove frontiere della fotografia…………………………………………………………pag. 6 Dietro un fragile display.………………………………………………………………………………………pag. 9 La fotografia interroga se stessa. Ugo Mulas a Napoli e a Milano…… ….…………pag. 12 Un biglietto per fuggire .………………………………………………………………………………………pag. 15 Vanessa Winship…………………………………………………………………………………………………..pag. 18 Addio a Phil Stern, star della fotografia.………………………………………………………………pag. 20 La storia della fotografia raccontata attraverso le mostre.…………………………………pag. 21 Se sembra una foto è meglio che lo sia.………………………………………………………………pag. 22 Sestri: Festival della Fotografia, in viaggio attraverso le ville..…………………………pag. 25 Le fanciulle Kejia, mostra fotografica di Zhen Li…….……………………………………………pag. 26 L'amara ricompensa del soldato Walter.………………………………………………………………pag. 27 Fotografia e mistero: i Casi Inrisolti.……………………………………………………………………pag. 30 Tutta La storia in un clic. Dondero alle Terme di Diocleziano.……………………………pag. 33 Eppur non si muove………………………………………………………………………………………………pag. 36 Lenny Kravitz, un libro con le sue foto scattate con la Leica………………………………pag. 40 Mr. Herschel, ritiri quelle parole……………………………………………………………………………pag. 41 Dove va la fotografia ? Colloquio a tre con Walter Guadagnini……………………………pag. 44 E' tua la foto? No, adesso -

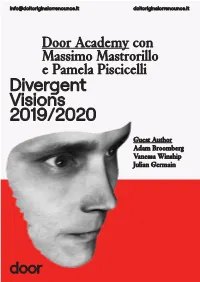

Academy 2020 Door

[email protected] doitoriginalorrenounce.it Door Academy con Massimo Mastrorillo e Pamela Piscicelli Divergent Visions 2019/2020 Guest Author Adam Broomberg Vanessa Winship Julian Germain door Door Academy @Adam Broomberg/Oliver Chanarin door Divergent academy Visions 2019/2020 Door Academy – Divergent visions, è un master internazionale specializzato nei moderni linguaggi della fotografia documentaria. Nella società dell’immagine l’ipervisibilità rende ciechi, insensibili, conformi anche quando non lo siamo. Obiettivo principale del master è imparare a guardare in una modalità diversa, che si discosti dalle mode e dalle didascalie del reale. Una visione capace di arrivare in profondità attraverso l’evocazione, l’immaginazione e l’indagine. Il master si terrà presso la sede di door, la durata sarà di otto mesi, dai primi di novembre 2019 fino ai primi di giugno 2020. Sarà tenuto da Massimo Mastrorillo/door, fotografo con un’esperienza pluriennale nel campo della didattica e vincitore di diversi premi internazionali e da Pamela Piscicelli/door, autrice, scrittrice e curatrice. Ad arricchire e completare il corso con la loro personale visione ci saranno tre workshop di due giorni con importanti e innovativi autori dello scenario fotografico internazionale: Adam Broomberg, Julian Germain, Vanessa Winship. Il corso diventa così vero e proprio laboratorio creativo di sperimentazione, basato sull’idea che lo sviluppo delle capacità dei singoli individui debba avvenire all’interno di un processo di apprendimento basato sulla condivisione e sulla collaborazione. Divergent Visions 2019-2020 door academy [email protected] 4 door Obiettivi academy del master • Sviluppare le capacità autoriali e creative, l’approccio tecnico e la consapevolezza degli studenti.