Textbooks for Film Music History: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM at CANNES British Entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’Ve Got to Talk About Kevin Dir

London May 10 2011: For immediate release BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM AT CANNES British entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’ve Got to Talk About Kevin dir. Lynne Ramsay UK Film Centre supports delegates with packed events programme 320 British films for sale in the market A Clockwork Orange in Cannes Classics The UK film industry comes to Cannes celebrating the selection of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin for the official competition line-up at this year’s festival, Duane Hopkins’s short film, Cigarette at Night, in the Directors’ Fortnight and the restoration of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, restored by Warner Bros; in Cannes Classics. Lynne Ramsay’s We Need To Talk About Kevin starring Tilda Swinton was co-funded by the UK Film Council, whose film funding activities have now transferred to the BFI. Duane Hopkins is a director who was supported by the UK Film Council with his short Love Me and Leave Me Alone and his first feature Better Things. Actor Malcolm McDowell will be present for the screening of A Clockwork Orange. ITV Studios’ restoration of A Night to Remember will be screened in the Cinema on the Beach, complete with deckchairs. British acting talent will be seen in many films across the festival including Carey Mulligan in competition film Drive, and Tom Hiddleston & Michael Sheen in Woody Allen's opening night Midnight in Paris The UK Film Centre offers a unique range of opportunities for film professionals, with events that include Tilda Swinton, Lynne Ramsay and Luc Roeg discussing We Need to Talk About Kevin, The King’s Speech producers Iain Canning and Gareth Unwin discussing the secrets of the film’s success, BBC Film’s Christine Langan In the Spotlight and directors Nicolas Winding Refn and Shekhar Kapur in conversation. -

Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2017 yS mposium Apr 12th, 3:00 PM - 3:30 PM Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M. DePree Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Composition Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Music Commons DePree, Kelsey M., "Cue the Music: Music in Movies" (2017). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 5. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2017/podium_presentations/5 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Music We Watch Kelsey De Pree Music History II April 5, 2017 Music is universal. It is present from the beginning of history appearing in all cultures, nations, economic classes, and styles. Music in America is heard on radios, in cars, on phones, and in stores. Television commercials feature jingles so viewers can remember the products; radio ads sing phone numbers so that listeners can recall them. In schools, students sing songs to learn subjects like math, history, and English, and also to learn about general knowledge like the days of the week, months of the year, and presidents of the United States. With the amount of music that is available, it is not surprising that music has also made its way into movie theatres and has become one of the primary agents for conveying emotion and plot during a cinematic production. -

The Soundtrack: Putting Music in Its Place

The Soundtrack: Putting Music in its Place. Professor Stephen Deutsch The Soundtrack Vol 1, No 1, 2008 tbc Intellect Press http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals.php?issn=17514193 Abstract There are currently many books and journals on film music in print, most of which describe music as a separate activity from film, applied to images most often at the very end of the production process by composers normally resident outside the filmic world. This article endeavours to modify this practice by placing music within the larger notion of “the soundtrack”. This new model assumes that irrespective of industrial determinants, the soundtrack is perceived by an audience as such a unity; that music, dialogue, effects and atmospheres are heard as interdependent layers in the sonification of the film. We often can identify the individual sonic elements when they appear, but we are more aware of the blending they produce when sounding together, much as we are when we hear an orchestra. To begin, one can posit a definition of the word ‘soundtrack’. For the purposes of this discussion, a soundtrack is intentional sound which accompanies moving images in narrative film1. This intentionality does not exclude sounds which are captured accidentally (such as the ambient noise most often associated with documentary footage); rather it suggests that any such sounds, however recorded, are deliberately presented with images by film-makers.2 All elements of the soundtrack operate on the viewer in complex ways, both emotionally and cognitively. Recognition of this potential to alter a viewer’s reading of a film might encourage directors to become more mindful of a soundtrack’s content, especially of its musical elements, which, as we shall see below, are likely to affect the emotional environment through which the viewer experiences film. -

To Film Sound Maps: the Evolution of Live Tone’S Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-Ho

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham From ‘Screenwriting for Sound’ to Film Sound Maps: The Evolution of Live Tone’s Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-ho Nikki J. Y. Lee and Julian Stringer Abstract: In his article ‘Screenwriting for Sound’, Randy Thom makes a persuasive case that sound designers should be involved in film production ‘as early as the screenplay…early participation of sound can make a big difference’. Drawing on a critically neglected yet internationally significant example of a creative alliance between a director and post- production team, this article demonstrates that early participation happens in innovative ways in today’s globally competitive South Korean film industry. This key argument is presented through close analysis of the ongoing collaboration between Live Tone - the leading audio postproduction studio in South Korea – and internationally acclaimed director Bong Joon-ho, who has worked with the company on all six of his feature films to date. Their creative alliance has recently ventured into new and ambitious territory as audio studio and director have risen to the challenge of designing the sound for the two biggest films in Korean movie history, Snowpiercer and Okja. Both of these large-scale multi-language movies were planned at the screenplay stage via coordinated use of Live Tone’s singular development of ‘film sound maps’. It is this close and efficient interaction between audio company and client that has helped Bong and Live Tone bring to maturity their plans for the two films’ highly challenging soundscapes. -

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: an Empirical Analysis of Music in Film

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: An Empirical Analysis of Music in Film Jon Gillick David Bamman School of Information School of Information University of California, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (Guha et al., 2015; Kociskˇ y` et al., 2017), natural language understanding (Frermann et al., 2017), Soundtracks play an important role in carry- ing the story of a film. In this work, we col- summarization (Gorinski and Lapata, 2015) and lect a corpus of movies and television shows image captioning (Zhu et al., 2015; Rohrbach matched with subtitles and soundtracks and et al., 2015, 2017; Tapaswi et al., 2015), the analyze the relationship between story, song, modalities examined are almost exclusively lim- and audience reception. We look at the con- ited to text and image. In this work, we present tent of a film through the lens of its latent top- a new perspective on multimodal storytelling by ics and at the content of a song through de- focusing on a so-far neglected aspect of narrative: scriptors of its musical attributes. In two ex- the role of music. periments, we find first that individual topics are strongly associated with musical attributes, We focus specifically on the ways in which 1 and second, that musical attributes of sound- soundtracks contribute to films, presenting a first tracks are predictive of film ratings, even after look from a computational modeling perspective controlling for topic and genre. into soundtracks as storytelling devices. By devel- oping models that connect films with musical pa- 1 Introduction rameters of soundtracks, we can gain insight into The medium of film is often taken to be a canon- musical choices both past and future. -

Pre-Assessment

Name: _________________________________________________ Date: ____________________________ Film Music Unit Pretest 6th Grade Music Multiple Choice 1. What is a melody? a. The main line in music b. The background line in music c. A song that we sing d. The rhythmic drive in music. 2. The line of music associated with Luke Skywalker in the movie Star Wars is called a ___________________. a. Sequence b. Ostinato c. Leitmotif d. Melody 3. What was the first movie with an entire original score? a. Gone with the Wind b. King Kong c. Casablanca d. Star Wars 4. What year did synthesizers become introduced as a part of film music? a. 1958 b. 1968 c. 1978 d. 1980 True or False 5. Music was included as a part of film starting with the first motion picture. True False 6. Film composers are not always well-respected in their careers. True False 7. Film music is played by a symphony. True False 8. Ascending melodies are generally happy, while descending melodies are generally sad. True False Matching Match each film with the composer who wrote the film score. 9. ___________ Star Trek a) Hans Zimmer 10. ___________ Edward Scissorhands b) Jerry Goldsmith 11. ___________ Titanic c) Max Steiner 12. ___________ The Lion King d) Danny Elfman 13. ___________ The Pink Panther e) John Williams 14. ___________ King Kong f) James Horner 15. ___________ Star Wars g) Henry Mancini Name: _________________________________________________ Date: ____________________________ Fill in the Blank Insert the best word into each blank. Not all words will be used. character consonance dissonance geographic harmony historic piano tension timbre 16. -

John Barry • Great Movie Sounds of John Barry

John Barry - Great Movie Sounds of John Barry - The Audio Beat - www.TheAudioBeat.Com 29.10.18, 1431 Music Reviews John Barry • Great Movie Sounds of John Barry Columbia/Speakers Corner S BPG 62402 180-gram LP 1963 & 1966/2018 Music Sound by Guy Lemcoe | October 26, 2018 uring his fifty-year career, composer John Barry won five Oscars and four Grammys. Among the scores he produced is my favorite, and what I consider his magnum opus, Dances with Wolves. Barry's music is characterized by bombast tempered with richly harmonious, "loungey," often sensuous melodies. Added to those are dramatic accents of brass, catchy Latin rhythms and creative use of flute, harp, timpani and exotic percussion (such as the talking drums, which feature prominently in the score from Born Free). The Kentonesque brass writing (trumpets reaching for the sky and bass trombones plumbing the lower registers), which helps define the Bond sound, no doubt stems from Barry’s studies with Stan Kenton arranger Bill Russo. I also hear traces of Max Steiner and Bernard Hermann in Barry's scores. When he used vocals, the songs often became Billboard hits. Witness Shirley Bassey’s work on Goldfinger, Tom Jones’s Thunderball, Matt Monro’s From Russia With Love and Born Free, Nancy Sinatra’s You Only Live Twice and Louis Armstrong’s On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Side one of Great Movie Sounds of John Barry features a half-dozen Bond-film flag-wavers -- two each from Thunderball and From Russia With Love and one each from Goldfinger and Dr. -

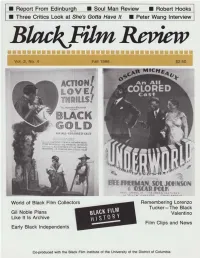

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

(LACMA) Hosted Its Ninth Annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, Honoring Artist Betye Saar and Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón

(Los Angeles, November 3, 2019)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosted its ninth annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, honoring artist Betye Saar and filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón. Co-chaired by LACMA trustee Eva Chow and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, the evening brought together more than 800 distinguished guests from the art, film, fashion, and entertainment industries, among others. This year’s gala raised more than $4.6 million, with proceeds supporting LACMA’s film initiatives and future exhibitions, acquisitions, and programming. The 2019 Art+Film Gala was made possible through Gucci’s longstanding and generous partnership. Additional support for the gala was provided by Audi. Eva Chow, co-chair of the Art+Film Gala, said, “I’m so happy that we have outdone ourselves again with the most successful Art+Film Gala yet. It was such a joy to celebrate Betye Saar and Alfonso Cuarón’s incredible creativity and passion, while supporting LACMA’s art and film initiatives. I couldn’t be more grateful to Alessandro Michele, Marco Bizzarri, and everyone at Gucci—our invaluable partner since the first Art+Film Gala—and to Anderson .Paak and The Free Nationals for making this evening one to remember.” “I’m deeply grateful to our returning co-chairs Eva Chow and Leonardo DiCaprio for helping us set another Art+Film Gala record,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “We honored two incredibly powerful artistic voices this year. Betye Saar has helped define the genre of Assemblage art for nearly seven decades, and recognition of her as one of the most important and influential artists working today is long overdue. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.