IIS Windows Server

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

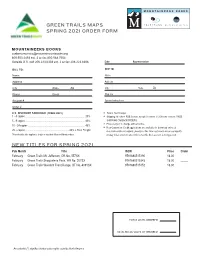

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

OREGON GEOLOGY Published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries

OREGON GEOLOGY published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries VOLUME 47. NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 1985 •-_Q OREGON GEOLOGY OIL AND GAS NEWS (ISSN 0164-3304) VOLUME 47, NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 1985 Columbia County Exxon Corporation spudded its GPE Federal Com. I on Published monthly by the Oregon Department of Geology and Min September I. The well name is a change from GPE Federal 2, eraI Industries (Volumes 1 through 40 were entitled The Ore Bin). permitted for section 3. T. 4 N .. R. 3 W. Proposed total depth is 12.000 ft. The contractor is Peter Bawden. Governing Board Donald A. Haagensen, Chairman ............. Portland Coos County Allen P. Stinchfield .................... North Bend Amoco Production Company is drilling ahead on Weyer Sidney R. Johnson. .. Baker haeuser "F" I in section 10, T. 25 S .. R. 10 W. The well has a projected total depth of 5,900 ft and is being drilled by Taylor State Geologist ..................... Donald A. Hull Drilling. Deputy State Geologist. .. John D. Beaulieu Publications Manager/Editor ............. Beverly F. Vogt Lane County Leavitt's Exploration and Drilling Co. has drilled Merle I to Associate Editor . Klaus K.E. Neuendorf a total depth of 2,870 ft and plugged the well as a dry hole. The well. in section 25. T. 16 S .. R. 5 W .. was drilled 2 mi southeast of Main Office: 910 State Office Building, 1400 SW Fifth Ave nue. Portland 9720 I, phone (503) 229-5580. Ty Settles' Cindy I. drilled earlier this year to 1.600 ft. A.M. Jannsen Well Drilling Co. -

Blast-Zone Hiking Raptor Viewing Wild Streaking

High Country ForN people whoews care about the West March 6, 2017 | $5 | Vol. 49 No. 4 | www.hcn.org 49 No. | $5 Vol. March 6, 2017 Raptor Viewing Blast-Zone Hiking Wild Streaking CONTENTS High Country News Editor’s note EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR/PUBLISHER Paul Larmer MANAGING EDITOR There and back again Brian Calvert SENIOR EDITOR Many years ago, I traveled Jodi Peterson abroad for the first time, to ART DIRECTOR visit a high school friend from Cindy Wehling DEPUTY EDITOR, DIGITAL Rock Springs, Wyoming, who Kate Schimel had been stationed by the U.S. ASSOCIATE EDITORS Tay Wiles, Army in Germany. On that trip, Maya L. Kapoor I nearly froze to death in the ASSISTANT EDITOR Paige Blankenbuehler Bavarian Alps, lost my passport D.C. CORRESPONDENT at a train station, and fell briefly in love with a Elizabeth Shogren woman I met in a Munich park. I spent the next WRITERS ON THE RANGE two decades traveling, as a student and journalist, EDITOR Betsy Marston learning about other places and people in an effort ASSOCIATE DESIGNER Brooke Warren to better understand myself. COPY EDITOR Every year, High Country News puts together Diane Sylvain a special travel issue. We do this because, in the CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Cally Carswell, Sarah pages of a typical issue, we are primarily concerned Gilman, Ruxandra Guidi, with the facts and forces that shape the American Glenn Nelson, West: the landscapes, water, people and wildlife Michelle Nijhuis, that make this region unique. In most stories, we try Jonathan Thompson FEATURES CORRESPONDENTS our best to serve as experienced guides, bringing Krista Langlois, Sarah our readers useful analysis and insight. -

Position Available Wildlife Habitat Conservati...Pdf

From: Amy Gladding Subject: Position Available: Wildlife Habitat Conservation Technician, USFS, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest http://crcareers.thegreatbasininstitute.org/careers/careers.aspx?rf=ECOLOG&req=2016-ACI-034 The Great Basin Institute, in cooperation with the U.S. Forest Service Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, is recruiting one (1) AmeriCorps Intern to serve as a Wildlife Habitat Conservation Technician to participate in wildlife population surveys, habitat assessment, habitat improvement project layout, and other duties related to habitat conservation efforts in the sagebrush ecosystem. The technician will work directly with a Forest Service Wildlife Biologist and Biological Technician to accomplish these tasks. Specific duties will include: • Maintain safety awareness and safe practices while travelling, conducting field work, and working in the office; • Drive on rough roads and navigate off-trail to remote survey sites and project locations. • Conduct sage-grouse lek counts/surveys. These surveys require wake-up times as early as 3 am to travel to remote sites and prepare for bird counts before sunrise. Will likely require camping during cold and winter like conditions. • Complete project preparation duties. Establish layout of treatment units by flagging and/or GPS boundaries for pinyon-juniper removal projects according to documented project designs. Establish pretreatment photo points. Inventory, map, and inspect fence lines, water developments, roads, and other features occurring in project areas. • Project inspections. Visit pinyon-juniper removal projects during and after implementation to ensure contract specifications were followed and habitat objectives were met. • Raptor nest checks. Visit project locations in advance of treatments to confirm presence/absence of raptor nests and make recommendations to avoid nest disturbance. -

A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene Glacial History and Paleoclimate Record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2005 A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene glacial history and paleoclimate record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States Shaun Andrew Marcott Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Glaciology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Marcott, Shaun Andrew, "A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene glacial history and paleoclimate record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States" (2005). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3386. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5275 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Shaun Andrew Marcott for the Master of Science in Geology were presented August II, 2005, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: (Z}) Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: MIchael L. Cummings, Chair Department of Geology ( ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Shaun Andrew Marcott for the Master of Science in Geology presented August II, 2005. Title: A Tale of Three Sisters: Reconstructing the Holocene glacial history and paleoclimate record at Three Sisters Volcanoes, Oregon, United States. At least four glacial stands occurred since 6.5 ka B.P. based on moraines located on the eastern flanks of the Three Sisters Volcanoes and the northern flanks of Broken Top Mountain in the Central Oregon Cascades. -

Mountain Ants of Nevada

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 38 Number 4 Article 2 12-31-1978 Mountain ants of Nevada George C. Wheeler Adjunct Research Associate, Desert Research Institute, Reno, Nevada Jeanette Wheeler Adjunct Research Associate, Desert Research Institute, Reno, Nevada Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Wheeler, George C. and Wheeler, Jeanette (1978) "Mountain ants of Nevada," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 38 : No. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol38/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. MOUNTAIN ANTS OF NEVADA George C. Wheeler' and Jeanette Wheeler' Abstract.- Introductory topics include "The High Altitude Environment," "Ants Recorded from High Alti- tudes," "Adaptations of Ants," "Mountain Ants of North America," and "The Mountains of Nevada." A Nevada mountain ant species is defined as one that inhabits the Coniferous Forest Biome or Alpine Biome or the ecotone between them. A table gives a taxonomic list of the mountain ants and shows the biomes in which they occur; it also indicates whether they occur in lower biomes. This list comprises 50 species, which is 28 percent of the ant fauna we have found in Nevada. Only 30 species (17 percent of the fauna) are exclusively montane; these are in the genera Mymiica, Manica, Stenamma, Leptothorax, Camponottis, Lasiiis, and Formica. The article concludes with "Records for Nevada Mountain Ants." All known records for each species are cited. -

Toiyabe National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan Table of Contents

United States Department of Agriculture NATIONAL FOREST PREFACE This National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan (Forest Plan) was developed to direct the management of the Toiyabe National Forest. The goal df the Plan is to provide a management program reflective of a mixture of management activities that allow use and protection of Forest resources; fulfill legislative requirements; and address local, regional, and national issues and concerns. To accomplish this, the Forest Plan: SPECIFIES THE STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES AND THE APPROXIMATE TIMING AND VICINITY OF THE PRACTICES NECESSARY TO ACHIEVE THAT DIRECTION; AND ESTABLISHES THE MONITORING AND EVALUATION REQUIREMENTS NEEDED TO ENSURE THAT THE DIRECTION IS CARRIED OUT AND TO DETERMINE HOW WELL OUTPUTS AND EFFECTS WERE PREDICTED. The Forest Plan will be reviewed (and updated if necessary) at least every five years. It will be revised on a IO- to 15-year cycle. Preparation of the Forest Plan is required by the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA) as amended by the National Forest Management Act (NFMA). Assessment of its environmental impacts is required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the implementing regulations of NFMA (36 WR 219). The Forest Plan replaces all previous resource management plans prepared for the Toiyabe National Forest. Upon approval of the Forest Plan, all subsequent activities affecting the Forest must be in compliance with the Forest Plan. In addition, all permits, contracts and other instruments for the use and 0 occupancy of National Forest System lands mst be in conformance with the Forest Plan. RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER PLANNINC LEVELS Development of this Forest Plan occurs within the framework of Forest Service regional and national planning. -

6 IA 6 – Volcano

6 IA 6 – Volcano THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY Table of Contents 1 Purpose ..................................................................... IA 6-1 2 Policies ...................................................................... IA 6-1 3 Situation and Assumptions ..................................... IA 6-2 4 Concept of Operations ............................................. IA 6-9 5 Roles and Responsibilities ...................................... IA 6-9 5.1 Primary Agency: Oregon Emergency Management ................. IA 6-9 5.2 Supporting Agencies .............................................................. IA 6-10 5.3 Adjunct Agencies ................................................................... IA 6-10 6 Hazard Specific Information – Volcano ................. IA 6-10 6.1 Definition ................................................................................ IA 6-10 6.2 Frequency .............................................................................. IA 6-11 6.3 Territory at Risk ...................................................................... IA 6-12 6.4 Effects .................................................................................... IA 6-12 6.5 Predictability ........................................................................... IA 6-13 7 Supporting Documents .......................................... IA 6-13 8 Appendices ............................................................. IA 6-13 IA 6-iii State of Oregon EOP Incident Annexes IA 6. Volcano THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY -

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 10, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) Sec. 1132. Extent of System. § 1110. Liability 1133. Use of wilderness areas. 1134. State and private lands within wilderness (a) United States areas. The United States Government shall not be 1135. Gifts, bequests, and contributions. liable for any act or omission of the Commission 1136. Annual reports to Congress. or of any person employed by, or assigned or de- § 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System tailed to, the Commission. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of (b) Payment; exemption of property from attach- policy; wilderness areas; administration for ment, execution, etc. public use and enjoyment, protection, preser- Any liability of the Commission shall be met vation, and gathering and dissemination of from funds of the Commission to the extent that information; provisions for designation as it is not covered by insurance, or otherwise. wilderness areas Property belonging to the Commission shall be In order to assure that an increasing popu- exempt from attachment, execution, or other lation, accompanied by expanding settlement process for satisfaction of claims, debts, or judg- and growing mechanization, does not occupy ments. and modify all areas within the United States (c) Individual members of Commission and its possessions, leaving no lands designated No liability of the Commission shall be im- for preservation and protection in their natural puted to any member of the Commission solely condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy on the basis that he occupies the position of of the Congress to secure for the American peo- member of the Commission. -

Glisan, Rodney L. Collection

Glisan, Rodney L. Collection Object ID VM1993.001.003 Scope & Content Series 3: The Outing Committee of the Multnomah Athletic Club sponsored hiking and climbing trips for its members. Rodney Glisan participated as a leader on some of these events. As many as 30 people participated on these hikes. They usually travelled by train to the vicinity of the trailhead, and then took motor coaches or private cars for the remainder of the way. Of the four hikes that are recorded Mount Saint Helens was the first climb undertaken by the Club. On the Beacon Rock hike Lower Hardy Falls on the nearby Hamilton Mountain trail were rechristened Rodney Falls in honor of the "mountaineer" Rodney Glisan. Trips included Mount Saint Helens Climb, July 4 and 5, 1915; Table Mountain Hike, November 14, 1915; Mount Adams Climb, July 1, 1916; and Beacon Rock Hike, November 4, 1917. Date 1915; 1916; 1917 People Allen, Art Blakney, Clem E. English, Nelson Evans, Bill Glisan, Rodney L. Griffin, Margaret Grilley, A.M. Jones, Frank I. Jones, Tom Klepper, Milton Reed Lee, John A. McNeil, Fred Hutchison Newell, Ben W. Ormandy, Jim Sammons, Edward C. Smedley, Georgian E. Stadter, Fred W. Thatcher, Guy Treichel, Chester Wolbers, Harry L. Subjects Adams, Mount (Wash.) Bird Creek Meadows Castle Rock (Wash.) Climbs--Mazamas--Saint Helens, Mount Eyrie Hell Roaring Canyon Mount Saint Helens--Photographs Multnomah Amatuer Athletic Association Spirit Lake (Wash.) Table Mountain--Columbia River Gorge (Wash.) Trout Lake (Wash.) Creator Glisan, Rodney L. Container List 07 05 Mt. St. Helens Climb, July 4-5,1915 News clipping. -

University of Nevada, Reno Reno at the Races

University of Nevada, Reno Reno at the Races: The Sporting Life versus Progressive Reform A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Emerson Marcus Dr. William D. Rowley/Thesis Advisor May 2015 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by EMERSON MARCUS Entitled Reno At The Races: Sporting Life Versus Progressive Reform be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS William D. Rowley, Ph.D., Advisor Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Alicia Barber, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2015 i Abstract The thesis examines horse race betting in the state of Nevada from 1915 to 1931 and how two opposing forces — sporting life and progressive reform — converged as state lawmakers passed progressive gambling legislation. While maybe not a catalyst, this legislation began Nevada’s slippery slope to becoming a wide-open gambling state. It examines how the acceptance of horse race betting opened the door for more ambitious forms of gambling while other states eventually followed Nevada’s lead and passed similar horse race betting law during the Great Depression. While other western states followed suit and legalized horse race betting during the Great Depression, month-long race meetings in Reno disbanded, as Nevada opened itself to wide-open gambling. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments iii I. Introduction 1 II. Gamblers, Turfites, Sports in a Changing State 8 From the Shadow of the Comstock 13 Crisis on the Turf 24 A True Sport 33 III.