Honors Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

Catalogue 2021

medir .cat Catalogue 2021 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Summary Clarinet 04 Sax 12 Historic Instruments 21 Bassoon 28 Oboe & English Horn 51 Traditional & Folk Instruments 73 Bag pipe & Uilleann Pipe 79 Cork 88 medir.cat 03 Clarinet medir.cat 04 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Medir Reeds C108 Bb Clarinet - 10 pieces C1085 Bb Clarinet - 5 pieces C117 Eb Clarinet - 10 pieces C1175 Eb Clarinet - 5 pieces Strenght: 1,5 / 2 / 2,5 / 3 / 3,5 / 4 / 4,5 / 5 C113 Bass Clarinet - 10 pieces C1135 Bass Clarinet - 5 pieces C108 C1085 Strenght: 2 / 2,5 / 3 / 3,5 / 4 / 4,5 C113 C108 medir.cat 05 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Medir Cane C101 Clarinet Tube Cane - 1 Kg Diameter: >25mm / Thickness >3 mm C103 Bb Clarinet Splits - 100 pieces Length: 69 mm / Thickness: >3 mm C104 Bb Clarinet Flat Blank - 100 pieces Length: 69 mm / Thickness: 2,2 mm C101 C103 C105 Bb Clarinet Blanks - 100 pieces Filled / Unfilled C106 Bb German Clarinet Blanks - 100 pieces C107 Eb Petit Clarinet Blanks - 100 pieces Filled C104 C105 medir.cat 06 Summary Clarinet Sax Historic Instruments Bassoon Oboe & English Horn Traditional & Folk Bag Pipe & Uilleann Pipe Cork Mouthpieces C110B Bb Clarinet C110E Eb Clarinet C110BS Bb Bass Clarinet Tip opening: close, 3, 4, 5, 6, open Ligatures C111 C111B Bb Clarinet C111E Eb Clarinet -

A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 4-2018 State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First- Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy Tamara Tanner University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Tanner, Tamara, "State of the Art: A Sampling of Twenty-First-Century American Baroque Flute Pedagogy" (2018). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 115. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY by Tamara J. Tanner A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Flute Performance Under the Supervision of Professor John R. Bailey Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 STATE OF THE ART: A SAMPLING OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN BAROQUE FLUTE PEDAGOGY Tamara J. Tanner, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Advisor: John R. Bailey During the Baroque flute revival in 1970s Europe, American modern flute instructors who were interested in studying Baroque flute traveled to Europe to work with professional instructors. -

2014 SSS Program.Indd

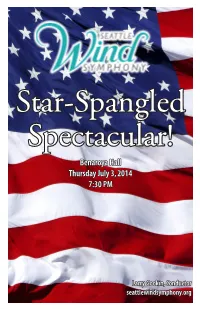

Star-Spangled Spectacular! Benaroya Hall Thursday July 3, 2014 7:30 PM Larry Gookin, Conductor seattlewindsymphony.org Program The Star-Spangled Banner ................... Orchestrated by John Philip Sousa Harmonized by Walter Damrosch / Arranged by Keith Brion America The Beautiful........................... Samuel Augustus Ward / Arranged by Carmen Dragon ~Welcome~ Liberty Bell March ................................ Orchestrated by John Philip Sousa Arranged by Keith Brion Seattle Wind Symphony is especially proud to present our second STAR SPANGLED SPECTACULAR musical salute Thoughts of Love .................................. Arthur Pryor to our nation. Our music for this “extravaganza” has been selected to put a song on your lips, tears in your eyes Matthew Grey, Trombone Soloist and a warm feeling of patriotism in your heart. We want to extend a special welcome and thanks to the Honor Oh Shenandoah ................................... Arranged by Frank Ticheli Guard from Joint Base Lewis McChord for presenting the colors to start our concert. We also want to thank the management of Benaroya Hall for their excellent leadership in our presentation today. We are very appreciative of Through The Air .................................... August Damm the participation of vocal soloist Sheila Houlahan and our narrator Dave Beck for sharing their talents, and for our Sara Jolivet, Piccolo Soloist instrumental soloists Michel Jolivet, Sara Jolivet, and Matt Grey. Thank You! Marching Through Georgia ................... John Philip Sousa Arranged by Keith Brion With today’s concert, Seattle Wind Symphony will have completed our third season. We recognize that most Rolling Thunder .................................... Henry Fillmore people have never heard high quality symphonic wind music, so we would like to invite you to our regular season performances. The 2014-2015 season dates are posted on our web site: www.seattlewindsymphony.org. -

2006 Heft 1 Zum Heft

MAGAZIN FÜR HOLZBLÄSER Eine Vierteljahresschrift · Einzelheft € 6,50 Heft 1/2006 Heft SSppiieellrrääuummee –– MOECK Seminare Termin: jeweils Samstags von 10.00 – 17.00 Uhr 2006 Ort: Kreismusikschule Celle, Kanonenstr. 4, 29221 Celle Carin van Heerden Peter Holtslag Der singende Telemann Der „gute“ Klang und die Blockflöte Seminar 1: 18. Februar 2006 – Widerspruch, Utopie oder Realität? Seminar 2: 6. Mai 2006 Werke von Georg Philipp Telemann für und mit Was macht einen guten Blockflötenklang aus und Blockflöte werden in diesem Workshop in Einzel- wie entsteht er? Welche Rolle spielt mein Körper? und Kammermusikstunden erarbeitet. Telemanns Muss man jeden Tag einen Marathon laufen und 2 Leitsatz Singen ist das Fundament zur Music in Liter Vitaminsaft trinken, um körperlich fit zu sein allen Dingen … Wer die Composition ergreifft, für den guten Klang? Reicht es schon aus, ein muß in seinen Sätzen singen soll die gemeinsame Instru ment der Spitzenklasse zu kaufen? Welche Arbeit an seinen Solo- und Kammermusikwerken Rol le spielen Vorstellungsvermögen und Suggesti- prägen. Eingeladen sind alle Block flötistInnen die vität? Welcher Klang passt zu welcher Musik? Wel- das Melodische bei Telemann lieben. che aufführungspraktischen Tendenzen spielen Ein Cembalo in 440 und 415 Hz sowie ein Beglei- eine Rolle für den Klang? Und: was bedeutet ter stehen bei Bedarf zur Verfügung. eigentlich „guter“ Geschmack und „guter“ Klang? In der ersten Stunde findet eine Einführung ins Folgende Werke können u. a. erarbeitet werden: Thema statt, veranschaulicht mit Klangbeispielen. – 6 Partitas (Die kleine Kammermusik für Block - Dann folgen gemeinsame Übungen und das Erar- flöte und B.c.) beiten von Stücken. – 12 Fantasien für Blockflöte solo Literaturvorschläge: – Sonaten für Altblockflöte und B.c. -

47Th Idrs Conference

SPECIAL ISSUE 47TH IDRS CONFERENCE AUG 28TH TO SEPT 1ST 2018 GRANADA, SPAIN Sophie Dartigalongue performing Jolivet Concerto with the Orquesta Ciudad de Granada. GRANADA SPECIAL ISSUE 2018 the taxis were the cleanest Introduction in the world and the drivers exceedingly honest, the history Contents from The Editor and architecture captivating, the Two years ago I announced at flamenco exhilarating, and then a meeting of the ADRSSA that there was the conference … 4 A Message from Sarah I was going to Granada to attend five days of a multiple number of Roper, IDRS 2018 the IDRS Conference before I sessions to choose from at any Conference Coordinator became too old to travel! given moment of the day. My flippant question “who’s Whatever your interest – baroque/ 6 Granada! coming with me?” prompted early music, chamber music, From The President an enthusiastic and immediate bassoon quartets, oboe ensembles, BY DR MARK GAYDON response of “I will!” from more than flamenco, master classes, one person. contemporary repertoire, audition 8 A Double Take on the The idea gained momentum and excerpts, technique, competitions, Double Reed picked up others from Adelaide performance tips, trying like a snowball rolling down a hill, instruments, trying reeds, selecting BY GRAHAM NORTON especially once the promotional cane, perusing music, instrument accessories – it was all there, and YouTube clip went viral extolling 10 Session Reviews the beauty and culture of Granada. of course, concerts, concerts and more concerts to wallow in. This conference captured the 15 Memorable Oboe hearts and imagination of double The collegiality, common Moments from IDRS reed players the world over and interest and passion for playing attracted some 1200 registrants, double reed instruments was Granada 2018 along with the push to break overwhelming. -

The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1966 The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions J. Wayne Johnson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, J. Wayne, "The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions" (1966). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2804. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IDENTIFICATION OF BAS~C PROBLEMS FOUND IN THE BASSOON PARTS OF A SELECTED GROUP OF BAND COMPOSITI ONS by J. Wayne Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the r equ irements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Music Education UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan , Ut a h 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BASSOON 3 THE I NSTRUMENT 20 Testing the bassoon 20 Removing moisture 22 Oiling 23 Suspending the bassoon 24 The reed 24 Adjusting the reed 25 Testing the r eed 28 Care of the reed 29 TONAL PROBLEMS FOUND IN BAND MUSIC 31 Range and embouchure ad j ustment 31 Embouchure · 35 Intonation 37 Breath control 38 Tonguing 40 KEY SIGNATURES AND RELATED FINGERINGS 43 INTERPRETIVE ASPECTS 50 Terms and symbols Rhythm patterns SUMMARY 55 LITERATURE CITED 56 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

The Rise and Fall of the Bass Clarinet in a the RISE and FALL of the BASS CLARINET in A

Keith Bowen - The rise and fall of the bass clarinet in A THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BASS CLARINET IN A Keith Bowen The bass clarinet in A was introduced by Wagner in Lohengrin in 1848. Unlike the bass instruments in C and Bb, it is not known to have a history in wind bands. Its appearance was not, so far as is known, accompanied by any negotiations with makers. Over the next century, it was called for by over twenty other composers in over sixty works. The last works to use the bass in A are, I believe, Strauss’ Sonatine für Blaser, 1942, and Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie (1948, revised 1990) and Gunther Schuller’s Duo Sonata (1949) for clarinet and bass clarinet. The instrument has all but disappeared from orchestral use and there are very few left in the world. It is now often called obsolete, despite the historically-informed performance movement over the last half century which emphasizes, inter alia, performance on the instruments originally specified by the composer. And the instrument has been largely neglected by scholars. Leeson1 drew attention to the one-time popularity and current neglect of the instrument, in an article that inspired the current study, and Joppig2 has disussed the use of the various tonalities of clarinet, including the bass in A, by Gustav Mahler. He pointed out that the use of both A and Bb clarinets in both soprano and bass registers was absolutely normal in Mahler’s time, citing Heinrich Schenker writing as Artur Niloff in 19083. Otherwise it has been as neglected in the literature as it is in the orchestra. -

The Clarinet and Piano

REVIEWS The explanations are succinct without CLARINET AND PIANO BOOKS sacrificing depth of understanding. The Brian Balmages. Dream Sonatina for Kornel Wolak. Articulation Types for pictures highlighting each muscle group are well presented and clear, and the clarinet and piano. Potenza Music, Clarinet. Music Mind Inc., 2017. 54 2015. Duration 10’30” $24.95 pp. PDF e-book $14.99, hard copy bibliography of materials for additional $19.99 study compliments his explanations nicely. American composer Brian Balmages I found this part of the book particularly (b. 1975) has written numerous works helpful. It directs the student to additional for wind and brass instruments. Dream exercises and methods that will help refine Sonatina was composed for clarinetist the technique in question. Articulation Marguerite Levin and premiered by Types for Clarinet is an excellent primer her in Weill Recital Hall, New York and first step in the understanding and City. Balmages fulfilled the specifics of application of the various available the commission by composing a work reflecting life in his 30s. For Balmages articulations. It was an enjoyable read, this centered on the birth of his two and I recommend it to anyone looking to children and three types of dreams they present articulation concepts to students experienced: daydreams, sweet dreams in a fresh and novel way. and bad dreams. The dreams are each Kornel Wolak’s book Articulation Types – Osiris Molina portrayed in a separate movement. for Clarinet is an extension of his work for The music is well-written, convincing Music Mind Inc. and his graduate research and of medium-hard difficulty, and it uses at the University of Toronto. -

New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon

Hayley Elizabeth Roud 300220780 NZSM596 Supervisor- Professor Donald Maurice Master of Musical Arts Exegesis 10 December 2010 New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon Contents 1 Introduction 3 2.1 History of the contrabassoon in the international context 3 Development of the instrument 3 Contrabassoonists 9 2.2 History of the contrabassoon in the New Zealand context 10 3 Selected New Zealand repertoire 16 Composers: 3.1 Bryony Jagger 16 3.2 Michael Norris 20 3.3 Chris Adams 26 3.4 Tristan Carter 31 3.5 Natalie Matias 35 4 Summary 38 Appendix A 39 Appendix B 45 Appendix C 47 Appendix D 54 Glossary 55 Bibliography 68 Hayley Roud, 300220780, New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon, 2010 3 Introduction The contrabassoon is seldom thought of as a solo instrument. Throughout the long history of contra- register double-reed instruments the assumed role has been to provide a foundation for the wind chord, along the same line as the double bass does for the strings. Due to the scale of these instruments - close to six metres in acoustic length, to reach the subcontra B flat’’, an octave below the bassoon’s lowest note, B flat’ - they have always been difficult and expensive to build, difficult to play, and often unsatisfactory in evenness of scale and dynamic range, and thus instruments and performers are relatively rare. Given this bleak outlook it is unusual to find a number of works written for solo contrabassoon by New Zealand composers. This exegesis considers the development of contra-register double-reed instruments both internationally and within New Zealand, and studies five works by New Zealand composers for solo contrabassoon, illuminating what it was that led them to compose for an instrument that has been described as the 'step-child' or 'Cinderella' of both the wind chord and instrument makers. -

The City, the Girls, the Composer…The Phenomenon

THE CITY, THE GIRLS, THE COMPOSER…THE PHENOMENON: INFLUENCES ON THE PERFORMANCE OF VIVALDI‟S BASSOON CONCERTOS AT THE OSPEDALE DELLA PIETÀ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Cynthia M. Duda August, 2009 THE CITY, THE GIRLS, THE COMPOSER…THE PHENOMENON: INFLUENCES ON THE PERFORMANCE OF VIVALDI‟S BASSOON CONCERTOS AT THE OSPEDALE DELLA PIETÀ Cynthia M. Duda Thesis Approved: Accepted: ______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks A. Toliver Dr. James M. Lynn ______________________________ ______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Galen S. Karriker Dr. George R. Newkome ______________________________ ______________________________ Department Chair Date Dr. William K. Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................1 Vivaldi......................................................................................................................3 Venice ......................................................................................................................6 The Ospedali ..........................................................................................................11 II. OSPEDALE DELLA PIETÀ ........................................................................................15 Daily Lives .............................................................................................................16