The New Nowness of Tapestry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

A Tapestry of Peoples

HIGH SCHOOL LEVEL TEACHING RESOURCE FOR THE PROMISE OF CANADA, BY CHARLOTTE GRAY Author’s Note Greetings, educators! While I was in my twenties I spent a year teaching in a high school in England; it was the hardest job I’ve ever done. So first, I want to thank you for doing one of the most important and challenging jobs in our society. And I particularly want to thank you for introducing your students to Canadian history, as they embark on their own futures, because it will help them understand how our past is what makes this country unique. When I sat down to write The Promise of Canada, I knew I wanted to engage my readers in the personalities and dramas of the past 150 years. Most of us find it much easier to learn about ideas and values through the stories of the individuals that promoted them. Most of us enjoy history more if we are given the tools to understand what it was like back then—back when women didn’t have the vote, or back when Indigenous children were dragged off to residential schools, or back when Quebecers felt so excluded that some of them wanted their own independent country. I wanted my readers to feel the texture of history—the sounds, sights and smells of our predecessors’ lives. If your students have looked at my book, I hope they will begin to understand how the past is not dead: it has shaped the Canada we live in today. I hope they will be excited to meet vivid personalities who, in their own day, contributed to a country that has never stopped evolving. -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

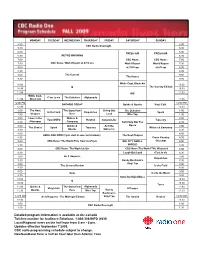

Rev-Radio One F 09

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:30 5:30 6:00 6:00 FRESH AIR FRESH AIR 6:30 METRO MORNING 6:30 7:00 CBC News: CBC News: 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 6/7/8 am World Report World Report 7:30 8:00 at 7/8/9 am at 8/9 am 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 White Coat, Black Art 10:00 Q The Sunday Edition 10:30 10:30 11:00 GO! 11:00 White Coat, C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada 11:30 Black Art 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM ONTARIO TODAY Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from Living Out The Debaters 1:00 In the Field Dispatches Spark 1:30 Chapter Here Loud Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Writers & 2:00 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Company Definitely Not The 2:30 3:00 Quirks & And the Opera 3:00 The Choice Spark Tapestry Writers & Company 3:30 Quarks Winner Is 3:30 4:00 4:00 HERE AND NOW (3 pm start in selected markets) The Next Chapter 4:30 Cross Country 4:30 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm BIG CITY SMALL Checkup 5:00 5:30 WORLD 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 7:00 As It Happens 7:00 Dispatches 7:30 Randy Bachman's 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review In the Field 8:30 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 10:00 Q 10:30 10:30 Tonic 11:00 Quirks & The Story from Afghanada 11:00 Vinyl Café A Propos 11:30 Quarks Here Wire Tap Randy 11:30 Bachman's 12:00 AM As It Happens - The Midnight Edition Vinyl Tap The Strand Rewind 12:00 AM 12:30 12:30 1:00 1:00 CBC Radio Overnight 1:30 1:30 Detailed program information is available at cbc.ca/radio Toll-free number for Audience Relations: 1-866-306-INFO (4636) Local/Regional news on the half hour from 6 am - 6 pm. -

ATA NL Winter 06 Vol32no4

Tapestry Topics A Quarterly Review of Tapestry Art Today www.americantapestryalliance.org Winter 2006 Vol 32 No 4 In This Issue Transition As Design Element Transitions and Joins. 3 By Kathe Todd Hooker Norwegian Dovetail Joins . 5 By Judy Ness Borders . 8 By Kathy Spoering Back to Borders . 10 By Sarah Swett Slits as Kilt Allusion . 12 Barbara Heller, "Nova Scotia Morning," 16" x 20" framed By Joan Baxter Point of Contact = Point of Power. 14 Barbara Heller Donates By Mary Zicafoose ATB6 Artists on Transitions . 15 Tapestry to ATA By Linda Rees Imagine owning a tapestry by Barbara Heller, one Book Review: Norwegian of North Americas most celebrated artist/weavers. Tapestry Weaving . 16 By Judy Ness Having one of her gorgeous pieces in your home Review: Gugger Petter: may be closer than you think. ATA is thrilled to The Dailies . 17 announce that Barbara has donated a tapestry entitled By Lany Eila “Nova Scotia Morning” for the purpose of a very Review: ATB6-More than One special anniversary fundraiser in 2007. Valued at Way of Visiting a Tapestry. 18 over $1,500, this beautiful landscape, measuring 16” By Elyse Koren-Camarra x 20” framed, will be raffled among donors to ATA’s Recently Exhibited Tapestries . 18 By Chrisitne Pradel Lien Silver Anniversary Campaign at our Anniversary The Crownpoint Navajo Rug party on April 28, 2007. More information about Auction. 19 this fundraiser will be coming in the mail soon, and By Karen Crislip we hope that all of our members will wish to con- Volunteers Mare it Happen – tribute $25 or more in exchange for the opportunity Barbara Heller . -

Radio One Summer 2011 FINAL.XLS

CBC Radio One Summer Schedule 2011 MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Science in 5:00 One Planet Discovery Click Health Check World in Progress The Curious Ear 5:00 Action Documentary On The 5:30 Your World HardTalk Assignment Hardtalk World Football One 5:30 Documentary 6:00 6:00 Local Morning Program 6:30 6:30 (5:30am start in selected markets) 7:00 Local Morning Program 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am CBC News: World Report 6/7/8/9 7:30 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 The Current 9:00 9:00 Out of Their Global The House 9:30 Shift Minds ReVision Quest Perspectives The Late Show 9:30 10:00 10:00 Being Jann The Sunday Edition 10:30 Q The Summer 10:30 11:00 This is That 11:00 White Coat Strange The Debaters Afghanada Know Your 11:30 Strange Animal 11:30 Black Art Animal Rights 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next Wachtel on the Living Out Spark 1:00 In the Field Dispatches The Debaters 1:30 Chapter Arts Loud ReVision Quest (4 PT) 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Tapestry 2:00 Your DNTO Spark Canada Live 2:30 Afternoon Rewind (3(3 PT, 4 MTMT)) 2:30 3:00 DNTO 3:00 Cross Country Writers & Quirks & And the Writers & Company Tapestry 3:30 in an Hour Company Quarks Winner Is (5PT/MT/CT) 3:30 4:00 Local Afternoon Program 4:00 The Next Chapter Cross Country 4:30 (3 pm start in selected markets) 4:30 Checkup 5:00 (1 PT, 2 MT, 3 CT, 5 AT) 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Regional Performance 5:30 5:30 CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six -

Blocksidewalk a Tapestry of Concerns

#BlockSidewalk O c t o b e r 20, 2019 A Tapestry of Concerns Public statements by 65+ Toronto-area individuals and organizations on Sidewalk Labs’ proposed test-bed neighbourhood on Toronto’s waterfront In July, a group of “30 civic leaders” in Toronto added their names to a public letter circulated by the Toronto Regional Board of Trade, with assistance from Sidewalk Labs, calling for Torontonians to support the Sidewalk Labs proposal.1 The letter reduced concerns with the project to “details” around “data governance…and a final path to rapid transit financing.” Torontonians’ concerns about Sidewalk Labs’ proposed test bed on public waterfront land, however, move well beyond “details,” and by the time TRBOT published its letter, expressions of concern had already outnumbered expressions of unreserved support by a large margin. Below are brief quotations from concerns about the Sidewalk Labs proposal circulated publicly by Toronto-area residents and organizations, written in their own words and made public at their own behest. The authors speak from different perspectives, walks of life and political persuasions, but all evidence thoughtfulness, care and a commitment to the future of our city. Waterfront Toronto would do well to listen to these voices. “[D]o we really need a coup d'état to get transit and nice paving stones?" -Toronto waterfront resident Julie Beddoes2 “The building designs illustrated could not be more conventional, not to say boring,” -Jack Diamond, five times winner of Governor General’s Medal in Architecture3 “[F]rustratingly abstract,” “unwieldy and repetitive,” and “overly focused on the ‘what’ rather than the ‘how.’” -Waterfront Toronto Digital Strategy Advisory Panel members4 Page 1 of 16 #BlockSidewalk “The issues that can’t be captured by the [Sidewalk Labs] plan, they’re the real problem. -

Radio One F 09 NB

New Brunswick MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:00 CBC Radio Overnight 5:30 Daybreak 5:30 6:00 6:00 6:30 Information Morning Weekend Mornings Weekend Mornings 6:30 7:00 CBC News: CBC News: 7:00 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 6/7/8 am World Report World Report 7:30 8:00 at 7/8/9 am at 8/9 am 8:00 8:30 Maritime Magazine 8:30 9:00 The Current 9:00 The House 9:30 9:30 10:00 White Coat, Black Art 10:00 The Sunday Edition 10:30 Q 10:30 11:00 11:00 GO! White Coat, C'est la vie The Debaters Afghanada Q 11:30 Black Art 11:30 12:00 PM 12:00 PM Maritime Noon Quirks & Quarks Vinyl Café 12:30 12:30 1:00 The Next The Story from Living Out The Debaters 1:00 In the Field Dispatches Spark 1:30 Chapter Here Loud Wire Tap 1:30 2:00 Ideas in the Writers & 2:00 Your DNTO Rewind Canada Live Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Company Definitely Not The 2:30 3:00 Opera 3:00 Close To Home Writers & Company 3:30 3:30 4:00 SHIFT 4:00 The Next Chapter All The Best 4:30 4:30 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Cross Country 5:00 Atlantic Airwaves 5:30 Checkup 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News:The World This Weekend 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud C'est la vie 6:30 7:00 As It Happens 7:00 Dispatches 7:30 Randy Bachman's 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review In the Field 8:30 8:30 9:00 9:00 Ideas Inside the Music 9:30 9:30 Saturday Night Blues 10:00 10:00 Q 10:30 10:30 Tonic 11:00 Quirks & The Story from Afghanada 11:00 Vinyl Café A Propos 11:30 Quarks Here Wire Tap Randy 11:30 Bachman's 12:00 AM 12:00 AM As It Happens - The Midnight Edition Vinyl Tap The Strand Rewind 12:30 12:30 1:00 1:00 CBC Radio Overnight 1:30 1:30 local/regional program Detailed program information is available at cbc.ca/radio Toll-free number for Audience Relations: 1-866-306-INFO (4636) Local/Regional news on the half hour from 6 am - 6 pm. -

CBC Radio One - Program Schedule Winter 2018-2019

CBC Radio One - Program Schedule Winter 2018-2019 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 6:00 6:00 6:30 Local Morning Program 6:30 (5:30am start in selected markets) Local Morning Program 7:00 CBC News: World Report 7:00 7:30 7:30 CBC News: World Report at 5/6/7/8 am at 6/7/8/9 am 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 9:00 The Current The The Sunday 9:00 9:30 House Edition 9:30 10:00 10:00 Day 6 10:30 q 10:30 11:00 Because News 11:00 The Doc Project The Debaters 11:30 Because News Under The Short Cuts Under The 11:30 (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) (3:30 NT) Influence Influence 12:00 PM Out 12:00 PM Local Noon Hour Program Quirks & Quarks in the 12:30 Open 12:30 1:00 The Next The Doc Project White Coat 1:00 Unreserved Tapestry Out in the Spark 1:30 Chapter Open Laugh Out Loud The Debaters (4 PT) 1:30 Podcast Now or 2:00 Ideas in the Playlist 2:00 Spark Never Canada Podcast Tapestry 2:30 Afternoon Live Playlist (3 PT, 4 MT) 2:30 Writers & 3:00 Writers & Quirks & Marvin’s Writers & 3:00 MyReclaimed Playlist Story From Here Now or Never Company 3:30 Company Quarks Room Company(5 CT, MT, PT) 3:30 Cross 4:00 Local Afternoon Program The Next Country 4:00 4:30 (3 pm start in selected markets) Chapter Checkup 4:30 (1 PT, 2MT, 5:00 CBC News: The World This Hour at 4/5 pm Regional 3CT, 5AT) 5:00 5:30 Performance 5:30 6:00 CBC News: The World at Six CBC News: The World This Weekend (7 AT) 6:00 6:30 Laugh Out Loud White Coat 6:30 7:00 As It Happens Unreserved 7:00 7:30 Randy Bachman’s (8 AT) 7:30 8:00 Vinyl Tap 8:00 The Current Review (8 AT) Reclaimed 8:30 (9 -

Signs of Our Faith: Being Uu Every Day

SIGNS OF OUR FAITH: BEING UU EVERY DAY A Tapestry of Faith Program for Children Grades 2-3 BY JESSICA YORK © Copyright 2013 Unitarian Universalist Association. This program and additional resources are available on the UUA.org web site at www.uua.org/tapestryoffaith. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHORS ...................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... 3 THE PROGRAM .................................................................................................................................................... 4 SESSION 1: SIGNS, SYMBOLS, AND RITUALS ............................................................................................ 12 SESSION 2: WE LEAD ....................................................................................................................................... 28 SESSION 3: OUR FAITH IS A JOURNEY ........................................................................................................ 37 SESSION 4: SEEKING KNOWLEDGE.............................................................................................................. 48 SESSION 5: WE REVERE LIFE ......................................................................................................................... 62 SESSION 6: SIGNS OF CARING ...................................................................................................................... -

Hilton Worldwide Franchising Lp Tapestry Collection By

HILTON WORLDWIDE FRANCHISING LP TAPESTRY COLLECTION BY HILTON FRANCHISE DISCLOSURE DOCUMENT CANADA Version Date: June 28, 2021 2021 Canada Tapestry IMPORTANT NOTICE If you are entitled to receive this Disclosure Document under the laws of the provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Ontario, or Prince Edward Island (“Disclosure Provinces”), then this Disclosure Document has been provided to you under the Alberta Franchises Act, the British Columbia Franchises Act, Manitoba’s The Franchises Act, the New Brunswick Franchises Act, the Ontario Arthur Wishart Act (Franchise Disclosure), 2000, or the Prince Edward Island Franchises Actor (the "Acts"), respectively, and we will observe the applicable waiting period after delivery of this Disclosure Document. The certificates of our officers that are required by various Disclosure Provinces are attached to this Disclosure Document after Article 29. If you reside in a province other than the Disclosure Provinces, or if you reside in a Disclosure Province but are subject to an exemption or exclusion under the Acts from the entitlement to receive a Disclosure Document, then we have provided this Disclosure Document to you for informational purposes only, and on a voluntary basis. The information in this Disclosure Document has been prepared pursuant to the laws of the Disclosure Provinces for distribution to prospective franchisees in those provinces who we are required to provide it to pursuant to the Acts. Accordingly, some of the information contained in the Disclosure Document is specific to prospective franchisees in one or more of the Disclosure Provinces only and, as a result, may not be correct for you or applicable to the operation of a franchise in your area. -

5-8 Student and Family Handbook 2020

Tapestry Charter School 65 Great Arrow Avenue Buffalo, NY 14216 (716) 332-0755 www.tapestryschool.org 5-8 Student and Family Handbook Covid-19 Edition 2020 - 2021 Lindsay Lee, Principal Amy Meshulam, Assistant Principal Ishmael Sprowal, Dean of Students Acknowledgement of 2020-2021 Student and Family Handbook Please review this handbook with your child. After reviewing, complete the form on this link. Welcome Students and Families Welcome to Tapestry Charter Middle School. As a member of our community, you are a part of a family that is founded on positive relationships, with a tradition of developing responsible civic-minded students with strong roots in the Greater Buffalo community. There are so many changes for the 2020-2021 school year, but we want to thank you for your patience, perseverance and understanding in these trying times. Please know that the safety of our students and staff is our number one priority and we are doing everything we possibly can to ensure a safe and smooth start to the school year. We are excited that for one year only, the fifth grade will be joining the middle school building due to social distancing guidelines across the Tapestry campus. While we will ensure that the fifth graders have minimal interaction with students in grades 6-8, we are happy to have these talented teachers and students with us for this year. Joining me again for the 2020-2021 academic school year to ensure a safe, relevant and rigorous learning experience for all students is Amy DiMaggio, 5-8 Assistant Principal. However, you may notice that her last name changed to Meshulam! Congratulations Mrs.