Historical Contingencies in the Ecology and Evolution of Species Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naturally Large Fires in Southern California

December 2011 CHAPTER MEETING Tuesday, December 20; 7 p.m. Room 104, Casa del Prado Balboa Park HOLIDAY GALA Heteromeles arbutifolia (Toyon) provides winter color. Toyon is a It’s time for our Holiday Gala Extravaganza on prominent component of the coastal sage scrub and is also often found in chaparral and mixed oak woodlands. It is also known by the common Tuesday, December 20! It’s a regular chapter names Christmas berry and California holly. Some say Hollywood, meeting day, so it’s already on your calendar. California was named for this species. And it’s a potluck, so no need to RSVP. Just come and bring your choicest delicacies (or most down-home goodies) to share. The BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chapter will supply the usual tasty hot water for coffee and tea, hot mulled cider, utensils, cups, MEETING napkins, and plates. You provide the stuff to put on the plates! There will be live music and Wednesday, December 7, 6:30 - 8:30 p.m., who knows what-all! monthly CNPS San Diego Chapter board meeting to be held at 4010 Morena Blvd, Suite 100, San Diego (Thomas Guide 1248 C4). Exit I-5 to Balboa Dr. east Bring your pictures of native plants, native and turn north on Morena Drive. Proceed 1/2 mile gardens, or whatever on a disk or thumb drive and make a u-turn at the Avati Street signal and turn and CNPS will provide a computer and into the driveway for 4010. Drive to the parking lot on projector. See you at the Gala! the west side (away from Morena). -

Atlas of the Flora of New England: Fabaceae

Angelo, R. and D.E. Boufford. 2013. Atlas of the flora of New England: Fabaceae. Phytoneuron 2013-2: 1–15 + map pages 1– 21. Published 9 January 2013. ISSN 2153 733X ATLAS OF THE FLORA OF NEW ENGLAND: FABACEAE RAY ANGELO1 and DAVID E. BOUFFORD2 Harvard University Herbaria 22 Divinity Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-2020 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Dot maps are provided to depict the distribution at the county level of the taxa of Magnoliophyta: Fabaceae growing outside of cultivation in the six New England states of the northeastern United States. The maps treat 172 taxa (species, subspecies, varieties, and hybrids, but not forms) based primarily on specimens in the major herbaria of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, with most data derived from the holdings of the New England Botanical Club Herbarium (NEBC). Brief synonymy (to account for names used in standard manuals and floras for the area and on herbarium specimens), habitat, chromosome information, and common names are also provided. KEY WORDS: flora, New England, atlas, distribution, Fabaceae This article is the eleventh in a series (Angelo & Boufford 1996, 1998, 2000, 2007, 2010, 2011a, 2011b, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c) that presents the distributions of the vascular flora of New England in the form of dot distribution maps at the county level (Figure 1). Seven more articles are planned. The atlas is posted on the internet at http://neatlas.org, where it will be updated as new information becomes available. This project encompasses all vascular plants (lycophytes, pteridophytes and spermatophytes) at the rank of species, subspecies, and variety growing independent of cultivation in the six New England states. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

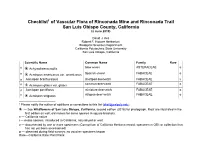

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report

APPENDIX D Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore EIR BIOLOGICAL TECHNICAL REPORT PROPOSED CARMAX AUTO SUPERSTORE PROJECT CITY OF OCEANSIDE, SAN DIEGO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: EnviroApplications, Inc. 2831 Camino del Rio South, Suite 214 San Diego, California 92108 Contact: Megan Hill 619-291-3636 Prepared by: 4629 Cass Street, #192 San Diego, California 92109 Contact: Melissa Busby 858-334-9507 September 29, 2020 Revised March 23, 2021 Biological Technical Report CarMax Auto Superstore TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 3 SECTION 1.0 – INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 6 1.1 Proposed Project Location .................................................................................... 6 1.2 Proposed Project Description ............................................................................... 6 SECTION 2.0 – METHODS AND SURVEY LIMITATIONS ............................................ 8 2.1 Background Research .......................................................................................... 8 2.2 General Biological Resources Survey .................................................................. 8 2.3 Jurisdictional Delineation ...................................................................................... 9 2.3.1 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jurisdiction .................................................... 9 2.3.2 Regional Water Quality -

Phylogeny of the Genus Lotus (Leguminosae, Loteae): Evidence from Nrits Sequences and Morphology

813 Phylogeny of the genus Lotus (Leguminosae, Loteae): evidence from nrITS sequences and morphology G.V. Degtjareva, T.E. Kramina, D.D. Sokoloff, T.H. Samigullin, C.M. Valiejo-Roman, and A.S. Antonov Abstract: Lotus (120–130 species) is the largest genus of the tribe Loteae. The taxonomy of Lotus is complicated, and a comprehensive taxonomic revision of the genus is needed. We have conducted phylogenetic analyses of Lotus based on nrITS data alone and combined with data on 46 morphological characters. Eighty-one ingroup nrITS accessions represent- ing 71 Lotus species are studied; among them 47 accessions representing 40 species are new. Representatives of all other genera of the tribe Loteae are included in the outgroup (for three genera, nrITS sequences are published for the first time). Forty-two of 71 ingroup species were not included in previous morphological phylogenetic studies. The most important conclusions of the present study are (1) addition of morphological data to the nrITS matrix produces a better resolved phy- logeny of Lotus; (2) previous findings that Dorycnium and Tetragonolobus cannot be separated from Lotus at the generic level are well supported; (3) Lotus creticus should be placed in section Pedrosia rather than in section Lotea; (4) a broad treatment of section Ononidium is unnatural and the section should possibly not be recognized at all; (5) section Heineke- nia is paraphyletic; (6) section Lotus should include Lotus conimbricensis; then the section is monophyletic; (7) a basic chromosome number of x = 6 is an important synapomorphy for the expanded section Lotus; (8) the segregation of Lotus schimperi and allies into section Chamaelotus is well supported; (9) there is an apparent functional correlation be- tween stylodium and keel evolution in Lotus. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

How Many of Cassini Anagrams Should There Be? Molecular

TAXON 59 (6) • December 2010: 1671–1689 Galbany-Casals & al. • Systematics and phylogeny of the Filago group How many of Cassini anagrams should there be? Molecular systematics and phylogenetic relationships in the Filago group (Asteraceae, Gnaphalieae), with special focus on the genus Filago Mercè Galbany-Casals,1,3 Santiago Andrés-Sánchez,2,3 Núria Garcia-Jacas,1 Alfonso Susanna,1 Enrique Rico2 & M. Montserrat Martínez-Ortega2 1 Institut Botànic de Barcelona (CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia s.n., 08038 Barcelona, Spain 2 Departamento de Botánica, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Salamanca, 37007 Salamanca, Spain 3 These authors contributed equally to this publication. Author for correspondence: Mercè Galbany-Casals, [email protected] Abstract The Filago group (Asteraceae, Gnaphalieae) comprises eleven genera, mainly distributed in Eurasia, northern Africa and northern America: Ancistrocarphus, Bombycilaena, Chamaepus, Cymbolaena, Evacidium, Evax, Filago, Logfia, Micropus, Psilocarphus and Stylocline. The main morphological character that defines the group is that the receptacular paleae subtend, and more or less enclose, the female florets. The aims of this work are, with the use of three chloroplast DNA regions (rpl32-trnL intergenic spacer, trnL intron, and trnL-trnF intergenic spacer) and two nuclear DNA regions (ITS, ETS), to test whether the Filago group is monophyletic; to place its members within Gnaphalieae using a broad sampling of the tribe; and to investigate in detail the phylogenetic relationships among the Old World members of the Filago group and provide some new insight into the generic circumscription and infrageneric classification based on natural entities. Our results do not show statistical support for a monophyletic Filago group. -

Benton County Prairie Species Habitat Conservation Plan

BENTON COUNTY PRAIRIE SPECIES HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN DECEMBER 2010 For more information, please contact: Benton County Natural Areas & Parks Department 360 SW Avery Ave. Corvallis, Oregon 97333-1192 Phone: 541.766.6871 - Fax: 541.766.6891 http://www.co.benton.or.us/parks/hcp This document was prepared for Benton County by staff at the Institute for Applied Ecology: Tom Kaye Carolyn Menke Michelle Michaud Rachel Schwindt Lori Wisehart The Institute for Applied Ecology is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization whose mission is to conserve native ecosystems through restoration, research, and education. P.O. Box 2855 Corvallis, OR 97339-2855 (541) 753-3099 www.appliedeco.org Suggested Citation: Benton County. 2010. Prairie Species Habitat Conservation Plan. 160 pp plus appendices. www.co.benton.or.us/parks/hcp Front cover photos, top to bottom: Kincaid’s lupine, photo by Tom Kaye Nelson’s checkermallow, photo by Tom Kaye Fender’s blue butterfly, photo by Cheryl Schultz Peacock larkspur, photo by Lori Wisehart Bradshaw’s lomatium, photo by Tom Kaye Taylor’s checkerspot, photo by Dana Ross Willamette daisy, photo by Tom Kaye Benton County Prairie Species HCP Preamble The Benton County Prairie Species Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) was initiated to bring Benton County’s activities on its own lands into compliance with the Federal and State Endangered Species Acts. Federal law requires a non-federal landowner who wishes to conduct activities that may harm (“take”) threatened or endangered wildlife on their land to obtain an incidental take permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. State law requires a non-federal public landowner who wishes to conduct activities that may harm threatened or endangered plants to obtain a permit from the Oregon Department of Agriculture. -

Plants of Piedras Pintadas Ridge, Lake Hodges James Dillane May, 1997 [email protected]

Plants of Piedras Pintadas Ridge, Lake Hodges James Dillane May, 1997 [email protected] Status N California native I introduced Scientific Name Common Name Status Amaranthaceae Amaranth Family Amaranthus blitoides Prostrate Amaranth N Anacardiaceae Sumac Family Malosma laurina Laurel Sumac N Rhus trilobata Skunkbrush N Toxicodendron diversilobum Poison Oak N Apiaceae Carrot Family Apiastrum angustifolium Mock Parsley N Bowlesia incana American Bowlesia N Daucus pusillus Rattlesnake Weed N Sanicula crassicaulis Pacific Sanicle N Tauschia arguta Southern Tauschia N Asclepiadaceae Milkweed Family Asclepias eriocarpa Indian Milkweed N Asteraceae Aster Family Acourtia microcephala Sacapellote N Ambrosia psilostachya Western Ragweed N Artemisia californica California Sagebrush N Baccharis pilularis Coyote Bush N Brickellia californica California Brickelbush N Centaurea melitensis Star-Thistle / Tocalote I Chaenactis artemisiifolia White Pincushin N Chaenactis glabriuscula San Diego Pincushion N Chamomilla suaveolens Pineapple Weed I Chrysanthemum coronarium Garland Chrysanthemum I Coreopsis californica California Coreopsis N Erigeron foliosus var. foliosus Fleabane Daisy N Eriophyllum confertiflorum var. confertiflorum Golden-Yarrow N Filago californica California Filago N Gnaphalium bicolor Bicolor Everlasting N Gnaphalium californicum California Everlasting N Gnaphalium canescens ssp. beneolens Fragrant Everlasting N Gnaphalium canescens ssp. microcephalum White Everlasting N Hazardia squarrosa ssp. grindelioides Sawtooth Goldenbush N Hedypnois cretica Hedypnois I Helianthus gracilentus Slender Sunflower N Heterotheca grandiflora Telegraph Weed N Hypochaeris glabra Smooth Cat's-Ear I Isocoma menziesii var. vernonioides Goldenbush N Lasthenia californica Goldfields N Lessingia filaginifolia California-Aster N Pentachaeta aurea Golden Daisy N Rafinesquia californica California Chicory n Senecio californicus California Butterweed N Sonchus oleraceus Common Sow Thistle I Stebbinoseris heterocarpa Stebbinoseris N Stephanomeria virgata ssp. -

Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 4 2011 Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B. Harper Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Sula Vanderplank Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Mark Dodero Recon Environmental Inc., San Diego, California Sergio Mata Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Jorge Ochoa Long Beach City College, Long Beach, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Alan B.; Vanderplank, Sula; Dodero, Mark; Mata, Sergio; and Ochoa, Jorge (2011) "Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol29/iss1/4 Aliso, 29(1), pp. 25–42 ’ 2011, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PLANTS OF THE COLONET REGION, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO, AND A VEGETATION MAPOF COLONET MESA ALAN B. HARPER,1 SULA VANDERPLANK,2 MARK DODERO,3 SERGIO MATA,1 AND JORGE OCHOA4 1Terra Peninsular, A.C., PMB 189003, Suite 88, Coronado, California 92178, USA ([email protected]); 2Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711, USA; 3Recon Environmental Inc., 1927 Fifth Avenue, San Diego, California 92101, USA; 4Long Beach City College, 1305 East Pacific Coast Highway, Long Beach, California 90806, USA ABSTRACT The Colonet region is located at the southern end of the California Floristic Province, in an area known to have the highest plant diversity in Baja California. -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise.