Colonial Pathways Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

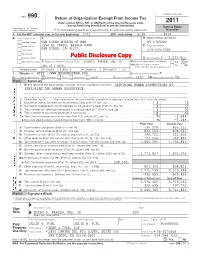

990 Informational Returns, Year Ending June 30, 2012

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code 2011 (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2011 calendar year, or tax year beginning 7/01 , 2011, and ending 6/30 , 2012 B Check if applicable: C D Employer Identification Number Address change SAN DIEGO MUSEUM OF MAN 95-1709290 Name change 1350 EL PRADO, BALBOA PARK E Telephone number SAN DIEGO, CA 92101 Initial return 619-239-2001 Terminated Amended return PublicDisclosureCopy G Gross receipts $ 2,021,845. Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: MICAH D. PARZEN, PHD, JD H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? YesX No H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No SAME AS C ABOVE If 'No,' attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt statusX 501(c)(3) 501(c) ()H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 J Website: G HTTP://WWW.MUSEUMOFMAN.ORG H(c) Group exemption number G K Form of organization:X Corporation Trust Association OtherG L Year of Formation: 1915 M State of legal domicile: CA Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: INSPIRING HUMAN CONNECTIONS BY EXPLORING THE HUMAN EXPERIENCE. 2 Check this box G if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Contact: Michael Warburton [email protected] Mobile (619) 850-4677 Website: Explorer.balboapark.org Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend San Diego, CA – March 31 – The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) announced that today the parkwide Balboa Park Explorer Pass program has resumed the sale of day and annual passes, in advance of more museums reopening this Easter weekend and beyond. “The Explorer Pass is the easiest way to visit multiple museums in Balboa Park, and is a great value when compared to purchasing admission separately,” said Kristen Mihalko, Director of Operations for BPCP. “With more museums reopening this Friday, we felt it was a great time to restart the program and provide the pass for visitors to the Park.” Starting this Friday, April 2nd, the nonprofit museums available to visit with the Explorer Pass include: • Centro Cultural de la Raza, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • Japanese Friendship Garden, 7 days/week • San Diego Air and Space Museum, 7 days/week • San Diego Automotive Museum, 6 days/week, closed Monday • San Diego Model Railroad Museum, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • San Diego Museum of Art, 6 days/week, closed Wednesdays • San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat), 5 days/week, closed Wednesday and Thursday The Fleet Science Center will rejoin the line up on April 9th; the Museum of Photographic Arts and the San Diego History Center will reopen on April 16th, and the Museum of Us will reopen on April 21st. -

The Hall of Mexico and Central America

The Hall of Mexico and Central America Teacher’s Guide See inside Panel 2 Introduction 3 Before Coming to the Museum 4 Mesoamericans in History 5-7 At the Museum 7 Related Museum Exhibitions 8 Back in the Classroom Insert A Learning Standards Bibliography and Websites Insert B Student Field Journal Hall Map Insert C Map of Mesoamerica Time Line Insert D Photocards of Objects Maya seated dignitary with removable headdress Introduction “ We saw so many cities The Hall of Mexico and Central America displays an outstanding collection of and villages built in the Precolumbian objects. The Museum’s collection includes monuments, figurines, pottery, ornaments, and musical instruments that span from around 1200 B.C. water and other great to the early 1500s A.D. Careful observation of each object provides clues about towns on the dry land, political and religious symbols, social and cultural traits, and artistic styles and that straight and characteristic of each cultural group. level causeway going WHERE IS MESOAMERICA? toward Mexico, we were Mesoamerica is a distinct cultural and geographic region that includes a major amazed…and some portion of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. The geographic soldiers even asked borders of Mesoamerica are not located like those of the states and countries of today. The boundaries are defined by a set of cultural traits that were shared by whether the things that all the groups that lived there. The most important traits were: cultivation of corn; a we saw were not a sacred 260-day calendar; a calendar cycle of 52 years; pictorial manuscripts; pyramid dream." structures or sacred “pyramid-mountains;” the sacred ballgame with ball courts; ritual bloodletting; symbolic imagery associated with the power of the ruler; and Spanish conquistador Bernal Díaz temples, palaces, and houses built around plazas. -

Ancient Egypt's

AMARNA ANCIENT EGYPT’S PLACE IN THE SUN ANCIENT EGYPT’S AMARNA PLACE IN THE SUN A LETTER FROM THE MUSEUM Dear Students, Of all the subjects that appeal to people of every age, blockbuster Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of and I know my own 11-year-old son would agree the Pharaohs, presented by Mellon Financial with me, Ancient Egypt and its mysteries must rank Corporation, beginning February 3, 2007 at The among the most intriguing. And here in West Franklin Institute. It will certainly be “The Year of Philadelphia, at the University of Pennsylvania Egypt” in Philadelphia, and I encourage you to visit Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, is one of both these wonderful exhibits. the finest collections of ancient Egyptian materials in the United States. Visit our exhibit to find out all about this mysterious city where young Tutankhamun grew up, a city built Come here almost any day and you can see an Eskimo in praise of the mighty god, the Aten, and where the whaling boat, view a Japanese Buddhist shrine, walk Pharaoh Akhenaten lived with his beautiful wife around the third largest sphinx known in the world, Nefertiti. Join us in our search for clues as to why the and look up at two of the great cedar totem poles of ancient city of Amarna existed only a few short years the American Northwest. Celebrate World Culture before it was abandoned again to the desert. Days here at the Museum, come to family workshops or enjoy our award- winning summer camp sessions. We look forward to welcoming you all to this great Penn Museum is alive with activities and opportunities museum. -

Go San Diego Card

Leisure Pass Group - Go San Diego Card - San Diego, CA For up-to-date information on available attractions, please check out: gocity.com/san-diego/en-us/AI-Guide With the Go San Diego All-Inclusive Pass, you can save up to 46% off retail prices to over 40 top attractions and activities for one low price, including San Diego Zoo*, Legoland California*, Safari Park*, bicycle tours, kayaking, and more. Enjoy the flexibility to choose attractions as you go and do as much as you want each day. After first attraction visit, tickets must be used on consecutive days. Admission to ALL of these following attractions! Note, some attractions may only be open seasonally. (Adult: 13+; Child: 3-12) Legoland® California* PETCO Park Tour San Diego Zoo* Whale Watch/Dolphin Cruise –Newport Landing San Diego Zoo Safari Park* San Diego History Center USS Midway Aircraft Carrier Museum Coronado Museum of History & Art SeaWorld San Diego* Museum of Making Music Hornblower Cruises or Whale Watching by Hornblower Hollywood Behind the Scenes Tour Cruises (Choice of 1) Coronado Full-Day Bike Rental San Diego Speed Boat Adventures Hollywood Museum Natural History Museum Whaley House The Fleet Science Center w/IMAX UTC Ice Sports Center Knott’s Berry Farm* San Diego Harbor 2-Hour SUP Belmont Park San Diego Harbor 2-Hour Kayak Rental Air & Space Museum San Diego Harbor 1-Hour Pedal Boat Rental La Jolla Full-Day Surfboard Rental Full Day Snorkel Adventure La Jolla 90-Minute Tandem Kayak Rental Pure Brewing Tasting (3 locations) La Jolla -

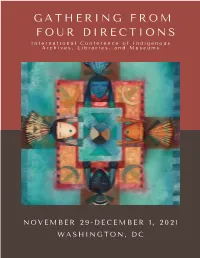

Program at a Glance, 7 Helpful Information, 9 Primary Focus Areas

GATHERING FROM FO UR DIRECTIONS International Conference of Indigenous Archives, Libraries, and Museums NOVEMBER 29-DECEMBER 1, 2021 WASHINGTON, DC INTERESTED IN WORKING WITH NATIVE AMERICAN COLLECTIONS? A PPLY F O R A 2022 ANNE RAY INTERNSHIP The Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, NM, offers two nine-month paid internships to college graduates or junior museum professionals. Internships include a salary, housing, book allowance, travel to one professional conference, and reimbursable travel to and from SAR. Interns participate in the daily activities relating to collections management, registration, education, as well as curatorial training. The IARC works with interns to achieve individual professional goals relating to indigenous cultural preservation in addition to providing broad-based training in the field of museology. APPLICATION DEADLINE: MARCH 1 Learn more and apply: internships.sarweb.org Call 505-954-7205 | Visit sarweb.org | Email [email protected] EXPLORING HUMANITY. UNDERSTANDING OUR WORLD. International Conference of Indigenous Archives, Libraries, and Museums GATHERING FROM FOUR DIRECTIONS November 29-December 1, 2021 Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE COLOR CODES To help you more easily locate the sessions that About the ATALM 2021 Artist and Artwork, 3 relate to your interests, sessions are color coded by primary focus area and than a secondary topic. The Schedule, 5 secondary topics correspond with the 10 Professional Development Certificates offered. Program -

Leisure Pass Group

Explorer Guidebook Choice of: San Diego Zoo or San Diego Zoo Safari Park Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open San Diego Zoo Getting In: Proceed directly to the turnstile for San Diego Zoo entry. An ID will be required when using the Go San Diego pass at San Diego Zoo. The last name of the purchaser must match the name on ID. Please Note: Hand stamp and ticket required for re-entry. No refunds or exchanges. Excludes special ticketed events & attractions. Parking is free. Includes unlimited use of Guided Bus Tour, Kangaroo Express Bus, and Skyfari Aerial Tram, as well as all regularly scheduled shows. San Diego Zoo Safari Park Getting In: Proceed directly to the turnstile fo entry and present your pass for admission. An ID will be required when using the Go San Diego pass at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. The last name of purchaser must match the name on ID. Hours of Operation San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Both are open daily from 9.00AM - 5.00PM. Getting There Address San Diego Zoo San Diego, CA 92101 US San Diego Speed Boat Adventures Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Reservations are required for San Diego Speed Boat Adventures. Reservation Instructions: Follow this link at least 24 hours in advance to make a reservation. A credit card will be required to hold your reservation, but you will only be charged the $50 cancellation fee if you are a no-show. Last-minute reservations are based on availability. Getting In: Please arrive 30 minutes prior to your scheduled departure. -

Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt

THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN RESEARCH CENTER IN EGYPT APRIL 22-25 2021 VIRTUAL ANNUAL MEETING | 2021 ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN RESEARCH CENTER IN EGYPT APRIL 22-25, 2021 VIRTUAL U.S. Office 909 North Washington Street 320 Alexandria, Virginia, 22314 703.721.3479 United States Cairo Center 2 Midan Simón Bolívar Garden City, Cairo, 11461 20.2.2794.8239 Egypt [email protected] ARCE EGYPT STAFF CAIRO Dr. Louise Bertini, Executive Director Dr. Yasmin El Shazly, Deputy Director for Research and Programs Dr. Nicholas Warner, Director of Cultural Heritage Projects Mary Sadek, Deputy Director for Government Affiliations Rania Radwan, Human Resources & Office Manager Djodi Deutsch, Academic Programs Manager Zakaria Yacoub, IT Manager Dania Younis, Communications Manager Miriam Ibrahim, Communications Associate Andreas Kostopoulos, Project Archives Specialist Mariam Foum, AEF Grant & Membership Administrator Sally El Sabbahy, Site Management and Planning Manager Noha Atef Halim, Finance Manager Yasser Tharwat, Financial & Reporting Manager Doaa Adel, Accountant Salah Metwally, Associate for Governmental Affairs Amira Gamal, Cataloging Librarian Usama Mahgoub, Supervising Librarian Reda Anwar, Administrative Assistance to Office Manager Doha Fathy, Digitization and Data Specialist Helmy Samir, Associate for Governmental Affairs Salah Rawash, Security & Reception Coordinator Abd Rabo Ali Hassan, Assistant to OM for Maintenance Affairs & Director’s Driver Ahmed Hassan, Senior Traffic Department Officer & Driver Ramadan Khalil Abdou, ARCE -

September/October 2020

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 ACTION EDUCATION ADVOCACY + PURPOSE CULTIVATING CIVIC ENGAGEMENT A message to our museum family DURING THESE UNPRECEDENTED TIMES, WE BELIEVE IN THE POWER OF COMMUNITY. As our nation confronts this period of uncertainty, we want to assure you that one thing has not changed, our support for museums and cultural sites across this country and the world. 10-31 is a family company and we stand with our museum family partners as we weather these historic times. We understand that capital purchases are not a part of your near-term goals, but we will be here for you when this world starts spinning again. We’re a business of relationships, not transactions. If there is anything we can help with, let us know and we will be there for you. Your Family at 10-31 and Art Display Essentials SIGNS 10-31.COM 800.862.9869 EXHIBITION DESIGN THE PRD GROUP SEPTEMBER OCTOBER 2020 ISSUE CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 5 From the President and CEO 6 By the Numbers 8 Point of View Get Out the Vote 12 Point of View Being Part of FEATURES the Solution 18 Space for Civic Dialogue 44 Alliance in Action A public education program at the Walker Art Center involving local artists invites 48 Reflection community conversation on immigration and citizenship. By Jacqueline Stahlmann 24 Civics in Action How can museums nurture the next generation of citizen-leaders? By Tony Pennay 28 Redefining ‘American’ A collection initiative at the National Museum of American History gives voice to undocumented immigrant activism. By Patricia Arteaga and Nancy Bercaw 32 Making the Abstract Real Minneapolis Cover: The US Capitol Visitor Center engages Artwork by @CeceCarpio student audiences near and far in civics Center, education. -

Balboa Park Parking & Circulation Discussion

BALBOA PARK PARKING & CIRCULATION DISCUSSION March 2021 FRIENDS OF BALBOA PARK Jack Carpenter, René Smith, Task Force Co-Chairs PURPOSE Goal To identify potential P&C partial solutions Request A determination by P&R on implementing any of these solutions Next Steps Should P&R favor any of these recommendations, Friends of Balboa Park will work closely with appointed staff to develop implementation plans BACKGROUND For decades, various studies have analyzed these issues for Balboa Park. In 2019, Friends volunteered to take a leadership role in studying solutions to the Park’s parking and circulation problems by establishing a working group of Parks & Recreation and park organizations’ leadership. Knowing that “everything is connected”, we purposely opted to: focus on the achievable to obtain “small victories”; be alert to the Balboa Park “Framework for the Future”; and, assist in developing transition strategies to the medium and longer term. BACKGROUND (CONT.) Over several months, with inclusive attendance at two stakeholder meetings, Discovery and Research & Analysis phases were completed. We are now ready to move to the Implementation Phase. CONTRIBUTORS TASK FORCE CO-CHAIRS Jack Carpenter René Smith Friends of Balboa Park, FAIA US Navy (Ret.) _______________________________________________________________________________________________ John Bolthouse Vicki Estrada Micah Parzen Friends of Balboa Park Estrada Land Planning Museum of Us Peter Comiskey Tomas Herrera-Mishler Melissa Peterman Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Balboa Park -

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Amarna Period Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77s6r0zr Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Williamson, Jacquelyn Publication Date 2015-06-24 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California AMARNA PERIOD ﻋﺼﺮ اﻟﻌﻤﺎرﻧﺔ Jacquelyn Williamson EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford WOLFRAM GRAJETZKI Area Editor Time and History University College London JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Williamson, 2015, Amarna Period. UEE. Full Citation: Williamson, Jacquelyn, 2015, Amarna Period. In Wolfram Grajetzki and Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002k2h3t 8768 Version 1, June 2015 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002k2h3t AMARNA PERIOD ﻋﺼﺮ اﻟﻌﻤﺎرﻧﺔ Jacquelyn Williamson Amarna Zeit Période d’Amarna The reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten/Amenhotep IV is controversial. Although substantial evidence for this period has been preserved, it is inconclusive on many important details. Nonetheless, the revolutionary nature of Akhenaten’s rule is salient to the modern student of ancient Egypt. The king’s devotion to and promotion of only one deity, the sun disk Aten, is a break from traditional Egyptian religion. Many theories developed about this era are often influenced by the history of its rediscovery and by recognition that Akhenaten’s immediate successors rejected his rule. ﺗﻌﺘﺒﺮ ﻓﺘﺮة ﺣﻜﻢ اﻟﻤﻠ��ﻚ اﺧﻨ��ﺎﺗﻮن / أﻣﻨﺤﻮﺗ��ﺐ اﻟﺮاﺑﻊ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻔﺘﺮات اﻟﻤﺜﯿﺮة ﻟﻠﺠ��ﺪل ، وﻋﻠﻰ اﻟﺮﻏﻢ ﻣﻦ وﺟﻮد أدﻟﺔ ﻗﻮﯾﺔ ﻣﺤﻔﻮظﺔ ﺗﺸ���ﯿﺮ إﻟﻰ ﺗﻠﻚ اﻟﺤﻘﺒﺔ اﻟﺘﺎرﯾﺨﯿﺔ ، إﻻ اﻧﮭﺎ ﻏﯿﺮ ﺣﺎﺳ���ﻤﺔ ﻟﻌﺪد ﻣﻦ اﻟﺘﻔﺎﺻ���ﯿﻞ اﻟﻤﮭﻤﺔ ، وﻣﻊ ذﻟﻚ ، ﻓﺈن اﻟﻄﺒﯿﻌﺔ اﻟﺜﻮرﯾﺔ ﻟﺤﻜﻢ اﻟﻤﻠﻚ اﺧﻨﺎﺗﻮن ھﻲ اﻟﺸ������ﺊ اﻟﻤﻠﺤﻮظ واﻟﺒﺎرز ﻟﻠﻄﺎﻟﺐ اﻟﺤﺪﯾﺚ ﻓﻲ ﻣﺼ����ﺮ اﻟﻘﺪﯾﻤﺔ. -

Recollections of Bill Coe and His Career As a Maya Archaeologist

RECOLLECTIONS OF BILL COE AND HIS CAREER AS A MAYA ARCHAEOLOGIST Part 2: After Tikal – Chalchuapa, Quirigua, In the Classroom, and at Home Compiled by Robert Sharer A tribute to the late William R. Coe was held at the Penn Museum on April 9, 2010, attended by a number of Bill‘s colleagues and former students. People spoke of his professional achievements and their recollections of working with Bill during his career at Penn spanning almost 40 years. The attendees also told a number of stories about Bill. After this event several people suggested that these recollections and stories should be collected and recorded so that they could be more widely shared and preserved. Word went out by email to colleagues and former students to contribute their accounts and over the following weeks and months many people shared their recollections and stories about Bill. Accordingly, we wish to thank the following colleagues who contributed to this cause, Wendy Ashmore, Wendy Bacon, Marshall Becker, Mary Bullard, Arlen Chase, Diane Chase, Pat Culbert, Ginny Greene, Peter Harrison, Anita Haviland, Bill Haviland, Chris Jones, Eleanor King, Joyce Marcus, Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Vivian Morales, Payson Sheets, and Bernard Wailes. We are all grateful to Anita Fahringer, who suggested these accounts could be published in The Codex. Thus the contributions from colleagues and students have been assembled, along with two more formal resumes of Bill‘s professional achievements, as a tribute to Bill, who was certainly a memorable mentor to us all. Because of their length, these accounts have been divided into two parts. The two formal tributes to Bill and part 1 of the recollections were published in The Codex., volume 19, issue 1-2 (October 2010-February 2011).