Recollections of Bill Coe and His Career As a Maya Archaeologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tik 02:Tik 02

2 The Ceramics of Tikal T. Patrick Culbert More than 40 years of archaeological research at Tikal have pro- duced an enormous quantity of ceramics that have been studied by a variety of investigators (Coggins 1975; Culbert 1963, 1973, 1977, 1979, 1993; Fry 1969, 1979; Fry and Cox 1974; Hermes 1984a; Iglesias 1987, 1988; Laporte and Fialko 1987, 1993; Laporte et al. 1992; Laporte and Iglesias 1992; Laporte, this volume). It could be argued that the ceram- ics of Tikal are better known than those from any other Maya site. The contexts represented by the ceramic collections are extremely varied, as are the formation processes to which they were subjected both in Maya times and since the site was abandoned. This chapter will report primarily on the ceramics recovered by the University of Pennsylvania Tikal Project between 1956 and 1970. The information available from this analysis has been significantly clar- ified and expanded by later research, especially that of the Proyecto Nacional Tikal (Hermes 1984a; Iglesias 1987, 1988; Laporte and Fialko 1987, 1993; Laporte et al. 1992; Laporte and Iglesias 1992; Laporte, this volume). I will make reference to some of the results of these later stud- ies but will not attempt an overall synthesis—something that must await Copyrighted Material www.sarpress.org 47 T. PATRICK C ULBERT a full-scale conference involving all of those who have worked with Tikal ceramics. Primary goals of my analysis of Tikal ceramics were to develop a ceramic sequence and to provide chronological information for researchers. Although a ceramic sequence was already available from the neighboring site of Uaxactun (R. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Takeshi Inomata Address Positions

Inomata, Takeshi - page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Takeshi Inomata Address School of Anthropology, University of Arizona 1009 E. South Campus Drive, Tucson, AZ 85721-0030 Phone: (520) 621-2961 Fax: (520) 621-2088 E-mail: [email protected] Positions Professor in Anthropology University of Arizona (2009-) Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in Environment and Social Justice University of Arizona (2014-2019) (Selected as one of the four chairs university-wide, that were created with a major donation). Associate Professor in Anthropology University of Arizona (2002-2009) Assistant Professor in Anthropology University of Arizona (2000-2002) Assistant Professor in Anthropology Yale University (1995-2000) Education Ph.D. Anthropology, Vanderbilt University (1995). Dissertation: Archaeological Investigations at the Fortified Center of Aguateca, El Petén, Guatemala: Implications for the Study of the Classic Maya Collapse. M.A. Cultural Anthropology, University of Tokyo (1988). Thesis: Spatial Analysis of Late Classic Maya Society: A Case Study of La Entrada, Honduras. B.A. Archaeology, University of Tokyo (1986). Thesis: Prehispanic Settlement Patterns in the La Entrada region, Departments of Copán and Santa Bárbara, Honduras (in Japanese). Major Fields of Interest Archaeology of Mesoamerica (particularly Maya) Politics and ideology, human-environment interaction, household archaeology, architectural analysis, performance, settlement and landscape, subsistence, warfare, social effects of climate change, LiDAR and remote sensing, ceramic studies, radiocarbon dating, and Bayesian analysis. Inomata, Takeshi - page 2 Extramural Grants - National Science Foundation, research grant, “Preceramic to Preclassic Transition in the Maya Lowlands: 1100 BC Burials from Ceibal, Guatemala,” (Takeshi Inomata, PI; Daniela Triadan, Co-PI, BCS-1950988) $298,098 (2020/6/3-8/31/2024). -

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

Kahk' Uti' Chan Yopat

Glyph Dwellers Report 57 September 2017 A New Teotiwa Lord of the South: K’ahk’ Uti’ Chan Yopat (578-628 C.E.) and the Renaissance of Copan Péter Bíró Independent Scholar Classic Maya inscriptions recorded political discourse commissioned by title-holding elite, typically rulers of a given city. The subject of the inscriptions was manifold, but most of them described various period- ending ceremonies connected to the passage of time. Within this general framework, statements contained information about the most culturally significant life-events of their commissioners. This information was organized according to discursive norms involving the application of literary devices such as parallel structures, difrasismos, ellipsis, etc. Each center had its own variations and preferences in applying such norms, which changed during the six centuries of Classic Maya civilization. Epigraphers have thus far rarely investigated Classic Maya political discourse in general and its regional-, site-, and period-specific features in particular. It is possible to posit very general variations, for example the presence or absence of secondary elite inscriptions, which makes the Western Maya region different from other areas of the Maya Lowlands (Bíró 2011). There are many other discursive differences not yet thoroughly investigated. It is still debated whether these regional (and according to some) temporal discursive differences related to social phenomena or whether they strictly express literary variation (see Zender 2004). The resolution of this question has several implications for historical solutions such as the collapse of Classic Maya civilization or the hypothesis of status rivalry, war, and the role of the secondary elite. There are indications of ruler-specific textual strategies when inscriptions are relatively uniform; that is, they contain the same information, and their organization is similar. -

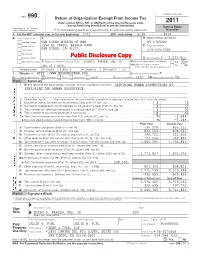

990 Informational Returns, Year Ending June 30, 2012

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code 2011 (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2011 calendar year, or tax year beginning 7/01 , 2011, and ending 6/30 , 2012 B Check if applicable: C D Employer Identification Number Address change SAN DIEGO MUSEUM OF MAN 95-1709290 Name change 1350 EL PRADO, BALBOA PARK E Telephone number SAN DIEGO, CA 92101 Initial return 619-239-2001 Terminated Amended return PublicDisclosureCopy G Gross receipts $ 2,021,845. Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: MICAH D. PARZEN, PHD, JD H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? YesX No H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No SAME AS C ABOVE If 'No,' attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt statusX 501(c)(3) 501(c) ()H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 J Website: G HTTP://WWW.MUSEUMOFMAN.ORG H(c) Group exemption number G K Form of organization:X Corporation Trust Association OtherG L Year of Formation: 1915 M State of legal domicile: CA Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: INSPIRING HUMAN CONNECTIONS BY EXPLORING THE HUMAN EXPERIENCE. 2 Check this box G if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Of the Kaminaljuyu Park

42 DOWN TO THE STERILE GROUND: “X-RAYS” OF THE KAMINALJUYU PARK Matilde Ivic de Monterroso Keywords: Maya archaeology, Guatemala, Altiplano, Kaminaljuyu, excavations, stratigraphy, Early Classic period, talud-tablero mode In the 1980’s and 1990’s, several salvage excavations were conducted at the southwest of Kaminaljuyu, the most important being those carried out during Project Miraflores I, Kaminaljuyu/San Jorge (Popenoe de Hatch 1997), and Miraflores II (Valdés 1997, 1998). These projects provided information on intensive agricultural systems, residential and ritual patterns, ceramic sequences, and evidence of the possible replacement of the Preclassic population by a new group in the Guatemala Valley, who arrived and took control of Kaminaljuyú during the Early Classic period. Nevertheless, one question that remained unanswered had to do with the relationship between Kaminaljuyu and Teotihuacan, reflected in the discoveries of Mounds A and B, and in the architecture of the Acropolis at Kaminaljuyu Park. For this reason, the park was the perfect place where to investigate this issue. This paper is providing new data that allows for evaluating the question of relationships between Kaminaljuyu and Teotihuacan. PROJECT DESIGN The investigation agreement anticipated the excavation of test units at the site periphery, and of a few others in the platforms supporting the mounds. No pits were planned inside the Acropolis or specifically on the mounds. The following facts were considered at the time of designing the project’s strategy: • The availability of the site plan drawn by the Tobacco and Salt Museum Archaeological Project (Ohi 1991). However, the use we made of this plan was limited, as it was elaborated with aerial photos, thus limiting the placement of the pits. -

Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Balboa Park Cultural Partnership Contact: Michael Warburton [email protected] Mobile (619) 850-4677 Website: Explorer.balboapark.org Balboa Park Explorer Pass Program Resumes Sales Before Holiday Weekend More Participating Museums Set to Reopen for Easter Weekend San Diego, CA – March 31 – The Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP) announced that today the parkwide Balboa Park Explorer Pass program has resumed the sale of day and annual passes, in advance of more museums reopening this Easter weekend and beyond. “The Explorer Pass is the easiest way to visit multiple museums in Balboa Park, and is a great value when compared to purchasing admission separately,” said Kristen Mihalko, Director of Operations for BPCP. “With more museums reopening this Friday, we felt it was a great time to restart the program and provide the pass for visitors to the Park.” Starting this Friday, April 2nd, the nonprofit museums available to visit with the Explorer Pass include: • Centro Cultural de la Raza, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • Japanese Friendship Garden, 7 days/week • San Diego Air and Space Museum, 7 days/week • San Diego Automotive Museum, 6 days/week, closed Monday • San Diego Model Railroad Museum, 3 days/week, open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday only • San Diego Museum of Art, 6 days/week, closed Wednesdays • San Diego Natural History Museum (The Nat), 5 days/week, closed Wednesday and Thursday The Fleet Science Center will rejoin the line up on April 9th; the Museum of Photographic Arts and the San Diego History Center will reopen on April 16th, and the Museum of Us will reopen on April 21st. -

Central America

Zone 1: Central America Martin Künne Ethnologisches Museum Berlin The paper consists of two different sections. The first part has a descriptive character and gives a general impression of Central American rock art. The second part collects all detailed information in tables and registers. I. The first section is organized as follows: 1. Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies 2. Known Sites: modes of iconographic representation and geographic context 3. Chronological sequences and stylistic analyses 4. Documentation and Known Sites: national inventories, systematic documentation and most prominent rock art sites 5. Legislation and institutional frameworks 6. Rock art and indigenous groups 7. Active site management 8. Conclusion II. The second section includes: table 1 Archaeological chronologies table 2 Periods, wares, horizons and traditions table 3 Legislation and National Archaeological Commissions table 4 Rock art sites, National Parks and National Monuments table 5 World Heritage Sites table 6 World Heritage Tentative List (2005) table 7 Indigenous territories including rock art sites appendix: Archaeological regions and rock art Recommended literature References Illustrations 1 Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies: Central America, as treated in this report, runs from Guatemala and Belize in the north-west to Panama in the south-east (the northern Bridge of Tehuantepec and the Yucatan peninsula are described by Mr William Breen Murray in Zone 1: Mexico (including Baja California)). The whole region is characterized by common geomorphologic features, constituting three different natural environments. In the Atlantic east predominates extensive lowlands cut by a multitude of branched rivers. They cover a karstic underground formed by unfolded limestone. -

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Stanley Brandes, Chair Professor William F. Hanks Professor Lawrence Cohen Professor William B. Taylor Spring 2011 Adoring our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México Copyright 2011 by Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Abstract Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Stanley S. Brandes The first decade of the 21st century has seen a transformation in national and regional Mexican politics and society. In the state of Yucatán, this transformation has taken the shape of a newfound interest in indigenous Maya culture coupled with increasing involvement by the state in public health efforts. Suicide, which in Yucatán more than doubles the national average, has captured the attention of local newspaper media, public health authorities, and the general public; it has become a symbol of indigenous Maya culture due to an often cited association with Ixtab, an ancient Maya ―suicide goddess‖. My thesis investigates suicide as a socially produced cultural artifact. It is a study of how suicide is understood by many social actors and institutions and of how upon a close examination, suicide can be seen as a trope that illuminates the complexity of class, ethnicity, and inequality in Yucatán. In particular, my dissertation –based on extensive ethnographic and archival research in Valladolid and Mérida, Yucatán, México— is a study of both suicide and suicide prevention efforts. -

An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala

Glyph Dwellers Report 65 October 2020 An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis A dichotomy between Olmec and Maya art styles on the stone monuments of the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj was proposed a number of years ago (e.g., Graham 1979). Researchers now recognize a more nuanced division between Olmec and developing Isthmian/Maya1 traditions (Graham 1989; Mora- Marín 2005; Popenoe de Hatch, Schieber de Lavarreda, and Orrego Corzo 2011; Schieber de Lavarreda 2020; Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010). John Graham proposed the term "Early Isthmian" rather than "Olmec" to describe examples of the Preclassic texts of southern Mesoamerica (Graham 1971:134). In this paper the term "Isthmian" is restricted to the script found on the Tuxtla Statuette (Holmes 1907), La Mojarra Stela 1 (Winfield Capitaine 1988), and related texts. Internal evidence within Isthmian texts themselves, specifically variation in both sign use and sign form, suggests that the origin of the Isthmian script dates significantly earlier than the long count dates on the two earliest known examples: La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette (Macri 2017a). Two items of stratigraphic evidence from Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas show a presence of the script at that site, beyond the Gulf region, pushing the origin of the script even further back in time (Macri 2017b). This report considers several texts from the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj, specifically two monuments, that have long count dates only slightly earlier those on La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette, to suggest an even broader geographic and temporal range for the Isthmian script tradition. -

Who Were the Maya? by Robert Sharer

Who Were the Maya? BY ROBERT SHARER he ancient maya created one of the Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador until the Spanish Conquest. world’s most brilliant and successful The brutal subjugation of the Maya people by the Spanish ca. 1470 CE civilizations. But 500 years ago, after the extinguished a series of independent Maya states with roots The Kaqchikel Maya establish a new Spaniards “discovered” the Maya, many as far back as 1000 BCE. Over the following 2,500 years scores highland kingdom with a capital at Iximche. could not believe that Native Americans of Maya polities rose and fell, some larger and more powerful had developed cities, writing, art, and than others. Most of these kingdoms existed for hundreds of ca. 1185–1204 CE otherT hallmarks of civilization. Consequently, 16th century years; a few endured for a thousand years or more. K’atun 8 Ajaw Europeans readily accepted the myth that the Maya and other To understand and follow this long development, Maya Founding of the city of Mayapan. indigenous civilizations were transplanted to the Americas by civilization is divided into three periods: the Preclassic, the “lost” Old World migrations before 1492. Of course archaeol- Classic, and the Postclassic. The Preclassic includes the ori- ogy has found no evidence to suggest that Old World intru- gins and apogee of the first Maya kingdoms from about 1000 sions brought civilization to the Maya or to any other Pre- BCE to 250 CE. The Early Preclassic (ca. 2000–1000 BCE) Columbian society. In fact, the evidence clearly shows that pre-dates the rise of the first kingdoms, so the span that civilization evolved in the Americas due to the efforts of the began by ca. -

Latepostclassicperiodceramics Ofthewesternhighlands,Guatemala

Yaxchilan Us um a c G in r t ij a Maya Archaeology Reports a Bonampak R lv i a v R e iv r er LatePostclassicPeriodCeramics ChiapasHighlands AltardeSacrificios DosPilas of theWesternHighlands,Guatemala Greg Borgstede Chinkultic MEXICO GUATEMALA Cancuen HUEHUETENANGO Lagartero ELQUICHE ALTAVERAPAZ – SanMiguelAcatan HUISTA ACATECREGION Jacaltenango Cuchumatan Mountains NorthernHighlands SanRafaelPetzal Nebaj Zaculeu SierraMadre Tajumulco his report describes the ceramics of the Late Postclassic 1986, Culbert 1965, Ichon 1987, Nance 2003a, Nance 2003b, and BAJAVERAPAZ Utatlan/Chisalin or Protohistoric period (AD 1200 to 1500) uncovered in a Weeks 1983. recent archaeological investigation in the western Maya The Late Postclassic period remains one of the most intensely highlands. The Proyecto Arqueológico de la Región Huista- studied in the Maya highlands, in terms of archaeology and CentralHighlands MixcoViejo T Acateco, directed by the author, investigated the region in the ethnohistory. The existence of competing Maya kingdoms, Iximche Cuchumatan Mountains currently occupied by the Huista and including those of the K’iche’, the Kaqchikel, and the Mam, Acatec Maya (Figure 1), documenting 150 archaeological sites and coupled with the persistence of written documentation LakeAtitlan GuatemalaCity an occupation sequence spanning the Terminal Preclassic to Late immediately prior to, during, and after the Spanish invasion, Postclassic/Protohistoric periods, AD 100 to 1525 (see Borgstede provide the Protohistoric period with an abundance of 2004). The modern towns of Jacaltenango and San Miguel Acatan anthropological data for understanding this complex era. are the center of the region. Archaeological evidence, particularly ceramics, has played a The ceramics described here are from the Late Postclassic role in interpreting the cultures, histories, and structures of these Archaeologicalsites period, also known as the “Protohistoric” period in the societies.