Glossary of Terms Glossary of Punchcutters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

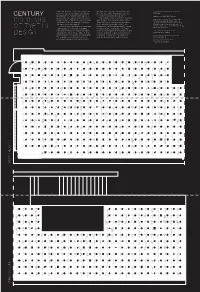

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Titling Fonts

Titling Fonts by Ilene Strizver HISTORICALLY, A “titling font” WAS A FONT OF METAL TYPE designed specifically for use at larger point sizes and display settings, including headlines and titles. Titling fonts, a specialized subset of display typefaces, differ from their text counterparts in that their scale, proportion and design details have been modified to look their best at larger sizes. They often have a more pronounced weight contrast (resulting in thinner thins), tighter spacing, and more condensed proportions than their text- sized cousins. Titling fonts may also have distinctive refinements that enhance their elegance and impact. Titling fonts are most often all-cap, single-weight variants created to complement text families, such as the These titling faces are stand-alone designs, rather than part of a larger family. a lowercase; Perpetua Titling has three ITC Golden Cockerel Titling (upper) is more streamlined than its non-titling cousin (lower). weights; and Forum Titling, based on a It also has different finishing details, as shown Frederick Goudy design, has small caps on the serif ending stroke of the C. in three weights that were added later. The overall design of most (but not all) titling fonts designed as part of the titling fonts is traditional or even historic Dante, Plantin, Bembo, Adobe in nature. In the days of metal type, Garamond Pro, and ITC Golden Cockerel titling capital letters took up the full typeface families. point size body height. For example, 48 point Perpetua titling caps were They can also be standalone designs, basically 48 points tall, whereas regular 48 point Perpetua was sized such that Dante Titling (upper) has greater weight such as Felix Titling, Festival Titling, and the tallest ascender and longest contrast and is slightly more condensed than Victoria Titling Condensed. -

First Line of Title

HEAVENLY HANDWRITING, TEUTONIC TYPE: FAITH AND SCRIPT IN GERMAN PENNSYLVANIA, CA. 1683 – 1855 by Alexander Lawrence Ames A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2014 © 2014 Alexander Lawrence Ames All Rights Reserved HEAVENLY HANDWRITING, TEUTONIC TYPE: FAITH AND SCRIPT IN GERMAN PENNSYLVANIA, CA. 1683 – 1855 by Alexander Lawrence Ames Approved: __________________________________________________________ Consuela Metzger, M.L.I.S. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Whom does one thank first for assistance toward completion of an academic project only brought to fruition by the support of dozens of scholars, professionals, colleagues, family members, and friends? I must first express gratitude to my relations, especially my mother Dr. Candice M. Ames and my brother Andrew J. Ames and his family, without whose support I surely never could have undertaken the journey from Minnesota to the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture nearly two years ago. At Winterthur, I found mentors who extended every effort to encourage my academic growth. Rosemary Krill, Brock Jobe, J. Ritchie Garrison, and Greg Landrey did much to help me explore new fields. I owe a particular debt to Winterthur’s art conservators. In one, Consuela Metzger, I found a thesis advisor willing to devote countless hours to guiding my intellectual exploration. -

The Graphie Latine Movement and the French Typography Manuel Sesma Prieto

UNIVERSITÉ PARIS 1 PANTHÉON-SORBONNE CENTRE DE RECHERCHE HiCSA (Histoire culturelle et sociale de l’art - EA 4100) UNE ÉMERGENCE DU DESIGN FRANCE, 20e SIÈCLE Sous la direction de Stéphane Laurent Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne THE GRAPHIE LATINE MOVEMENT AND THE FRENCH TYPOGRAPHY MANUEL SESMA PRIETO Pour citer cet article Manuel Sesma Prieto, « The Graphie Latine Movement and the French Typogra- phy », dans Stéphane Laurent (dir.), Une émergence du design. France 20e siècle, Paris, site de l’HiCSA, mis en ligne en octobre 2019, p. 126-143. THE GRAPHIE LATINE MOVEMENT AND THE FRENCH TYPOGRAPHY MANUEL SESMA PRIETO Associate professor, Facultad de Bellas Artes, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Introduction Most works dealing with the history of typography, many of Anglo-Saxon authors, reflect the period covered by the two decades after World War II practically dominated by neogrotesque typefaces. However, there were some reactions against this predominance, mainly from traditionalist positions that are rarely studied. The main objective of this research is thus to reveal the particular case of France, where there was widespread opposition to linear typefaces, which results into different manifestations in the field of national typography. This research wants therefore to situate the French typographical thought (which partially reflected the traditionalism of British typographical reformism led by Stanley Morison 1) within the history of European typography, and in a context dominated by the modern proposals arising mainly from Switzerland. This French thought is mostly shown in a considerable number of articles published in various specialist and professional press media, which perfectly reflected the general French atmosphere. -

HISTORY of the BOOK Chapter 5. the Invention and Spread of Printing

HISTORY of the BOOK Chapter 5. The Invention and Spread of Printing Blocks, type, paper, and markets, contact Impressions of wood blocks on cloth, or metal stamping in clay, wax, and leather, existed long before the idea of movable type was realized in Mainz. As we have seen, scrolls, tablets, and the bound codex book were all fully developed by the 15th century, and the range of materials pressed into use for writing included palm leaves, bark, walls, and skin in addition to vellum, parchment, papyrus, clay and paper. Of these, paper was the last to be invented, and until the creation of synthetic materials in recent centuries and digital modes of display, paper remained the most important and ubiquitous substrate for written language. And though the use of seals and stamps can be traced almost into prehistory, the idea of printing multiple copies of a text for purposes of distribution to a literate audience is more recent. The first printing for texts was most likely invented in China, with Chinese characters cut in the faces of individual wooden blocks, or whole texts cut in a single block.1 But the innovations brought to this art by Johann Gutenberg in the middle of the 15th century changed the scale and scope of printing.2 Not only was movable type a radical improvement in achieving efficiency for reproduction of multiple copies of a text, but the rationalization of labor that was embedded in this innovative shift created a model that would inform practices well into the industrial revolution hundreds of years later.3 Literacy, already on the rise in the late Middle Ages in Europe, and integral to certain communities in Asia, the Indian Subcontinent, and Northern Africa, would be fostered by increased availability of printed texts.4 Controversies would arise as debates about access to religious texts, in particular, would split along fault lines of belief. -

Faux Hands for Calligraphy Imitating Non-European Script

Faux Hands for Calligraphy Imitating Non-European Script THL Helena Sibylla – [email protected] As scribes in the SCA, we’re all familiar with a variety of European scripts from the Middle Ages. We’ve probably all dabbled at least a bit with calligraphic hands like Uncial, Carolingian Minuscule, Early Gothic, or Batarde. While many people in the SCA choose to portray European personas, there are an increasing number of people exploring non-European areas such as Islam and China. Beyond that, there are other scripts that exist around the main core of European writing that fit other personas such as Greek or Norse. If you have a scroll assignment for a person where a medieval European hand just won’t be suitable, there are a couple of options. One is to plug your text into a translation program and then writing in the original language. However, this runs the risk of someone who actually knows the language finding unintentional errors created by the translation software, which doesn’t always understand the quirks and idioms found in non-English languages. Creating a script with the look of a foreign hand that fits the culture of the recipient’s persona has the advantage of allowing the scribe to still write in English while creating a visual effect that is dramatically different from the typical SCA scroll. In addition to the examples provided here, I strongly recommend that you spend some time researching the script of the culture you’re planning to emulate. You will want to consider issues of punctuation and accent marks, as well as decorative letters, and upper and lower cases (if they are used). -

7332 EARLY MUSIC PRINTING TEXT PT 246X174mm

Early Music Printing in German-Speaking Lands Edited by Andrea Lindmayr-Brandl, Elisabeth Giselbrecht and Grantley McDonald First published 2018 ISBN: 978-1-138-24105-3 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-28145-2 (ebk) Chapter 8 The music editions of Christian Egenolff: a new catalogue and its implications Royston Gustavson (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) 8 The music editions of Christian Egenolff A new catalogue and its implications1 Royston Gustavson For Grantley McDonald Introduction Christian Egenolff is one of the most important music printers in the German-speaking area in the sixteenth century, in part because he was the first German printer to use single- impression movable type to print mensural music (which is much cheaper than the previous double-impression process), and in part because of his editions of Tenorlieder. Music, however, formed a very small part of his output, both in terms of total editions (sixteen of more than 600 editions) and of the physical scale of the editions. To place this into perspective, to print one copy of each of his known music editions (excluding the lost Gesangbüchlin) would have taken 282 sheets of paper; to print one copy of his 1534 bible (VD16 B 2692) took 290 sheets of paper. Previous catalogues of Egenolff’s music editions have been incomplete, although that by Hans-Christian Müller in 1964 was an outstanding version based on the evidence known at that time.2 A third of Egenolff’s extant editions have until now remained without a known title as the title pages were missing, just over half have had a contested date of printing, and two works have been believed to exist in two editions, whereas there is only one edition, but two issues, of each. -

Scribe Attribution for Early Medieval Handwriting by Means of Letter Extraction and Classification and a Voting Procedure for La

2014 22nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition Scribe attribution for early medieval handwriting by means of letter extraction and classification and a voting procedure for larger pieces Mats Dahllof¨ Dept of Linguistics and Philology and Dept of Information Technology, Division of Visual Information and Interaction, Uppsala University, Sweden E-mail: mats.dahllof@lingfil.uu.se Abstract—The present study investigates a method for the a discipline tend to be difficult to communicate, to reproduce, attribution of scribal hands, inspired by traditional palaeography and to validate (see Stokes [10]). By contrast, a computer- in being based on comparison of letter shapes. The system aided palaeography, making use of techniques inspired by was developed for and evaluated on early medieval Caroline those developed in forensic analysis of modern handwriting, minuscule manuscripts. The generation of a prediction for a page will be better equipped to characterize historical writing in image involves writing identification, letter segmentation, and precise and quantitative terms, and to work with models which letter classification. The system then uses the letter proposals to predict the scribal hand behind a page. Letters and sequences of can be objectively validated. connected letters are identified by means of connected component This paper describes a method for attributing pieces of labeling and split into letter-size pieces. The hand (and character) handwriting to scribes by extracting plausible letter candidates prediction makes use of a dataset containing instances of the from manuscript pages. The proposal is inspired by traditional letters b, d, p, and q, cut out from manuscript pages whose scribal origin is known. -

52Nd California International Antiquarian Book Fair List

52nd California International Antiquarian Book Fair List February 8 thru 10, 2019 John Howell for Books John Howell, member ABAA, ILAB, IOBA 5205 ½ Village Green, Los Angeles, CA 90016-5207 310 367-9720 www.johnhowellforbooks.com [email protected] THE FINE PRINT: All items offered subject to prior sale. Call or e-mail to reserve, or visit us at www.johnhowellforbooks.com, where all the items offered here are available for purchase by Credit Card or PayPal. Checks payable to John Howell for Books. Paypal payments to: [email protected]. All items are guaranteed as described. Items may be returned within 10 days of receipt for any reason with prior notice to me. Prices quoted are in US Dollars. California residents will be charged applicable sales taxes. We request prepayment by new customers. Institutional requirements can be accommodated. Inquire for trade courtesies. Shipping and handling additional. All items shipped via insured USPS Mail. Expedited shipping available upon request at cost. Standard domestic shipping is $ 5.00 for a typical octavo volume; additional items $ 2.00 each. Large or heavy items may require additional postage. We actively solicit offers of books to purchase, including estates, collections and consignments. Please inquire. This list prepared for the 52nd California International Antiquarian Book Fair, coming up the weekend of February 4 thru 11, 2019 in Oakland, California, contains 36 items including fine press material, leaf books, typography, and California history. Look for me in Booth 914, for more interesting material. John Howell for Books !3 1 [Ashendene Press] ASSISI, Francesco di (1181-1226). I Fioretti del Glorioso Poverello di Cristo S. -

Five Centurie< of German Fraktur by Walden Font

Five Centurie< of German Fraktur by Walden Font Johanne< Gutenberg 1455 German Fraktur represents one of the most interesting families of typefaces in the history of printing. Few types have had such a turbulent history, and even fewer have been alter- nately praised and despised throughout their history. Only recently has Fraktur been rediscovered for what it is: a beau- tiful way of putting words into written form. Walden Font is proud to pres- ent, for the first time, an edition of 18 classic Fraktur and German Script fonts from five centuries for use on your home computer. This booklet describes the history of each font and provides you with samples for its use. Also included are the standard typeset- ting instructions for Fraktur ligatures and the special characters of the Gutenberg Bibelschrift. We hope you find the Gutenberg Press to be an entertaining and educational publishing tool. We certainly welcome your comments and sug- gestions. You will find information on how to contact us at the end of this booklet. Verehrter Frakturfreund! Wir hoffen mit unserer "“Gutenberg Pre%e”" zur Wiederbelebung der Fraktur= schriften - ohne jedweden politis#en Nebengedanken - beizutragen. Leider verbieten un< die hohen Produktion<kosten eine Deutsche Version diese< Be= nu@erhandbüchlein< herau<zugeben, Sie werden aber den Deutschen Text auf den Programmdisketten finden. Bitte lesen Sie die “liesmich”" Datei für weitere Informationen. Wir freuen un< auch über Ihre Kommentare und Anregungen. Kontaktinformationen sind am Ende diese< Büchlein< angegeben. A brief history of Fraktur At the end of the 15th century, most Latin books in Germany were printed in a dark, barely legible gothic type style known asTextura . -

Writing Styles Which Make It Impossible to Segment Lines Into Words Without Using Lexical/Syntactic Knowledge1

Writing styles which make it impossible to segment lines into words without using lexical/syntactic knowledge1 Most (or all) writing systems were originated and then evolved as a means to render speech into some tangible form which could be easily disseminated and preserved for future reference. We call \text" the result of such a rendering process. Since text was mainly aimed at somehow mimicking the speech events to be rendered, it is no surprise that most forms of early writing did not care at all about separation of the text into words. Many writing styles went in this way over the millennia. Scriptio continua is still in use in Thai, as well as in other Southeast Asian alphasyllabaric systems and in languages that use Chinese characters. Nowadays, there are millions of preserved documents written in writing styles where word separa- tion is inexistent or highly inconsistent. Clearly, the only possibility to actually read and understand this kind of documents (for humans and machines alike), is by making use of lexical and syntactical knowledge about the language from which the text was produced. In this Annex we show a few examples of some of the most important of these writing styles which were widely used in Europe at least until the XVI century. \Escritura Cortesana" was widely used in edicts and other documents in the Castillan courts through the XV and XVI centuries in Spain. See examples in Figure 1. \Procesal encadenada" was a Spanish writing style, also widely used in the XVI century in Spain in the notarial ambit and by the Audience scribes.