ZANU-PF's Imaginations of the Heroes Acre, Heroes and Construction Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Rhodesia to Zimbabwe.Pdf

THE S.A. ' "!T1!TE OF INTERNATIONAL AFi -! NOT "(C :.-_ .^ FROM RHODESIA TO ZIMBABWE Ah Analysis of the 1980 Elections and an Assessment of the Prospects Martyn Gregory OCCASIONAL. PAPER GELEEIMTHEIOSPUBUKASIE DIE SUID-AFRIKAANSE INSTITUUT MN INTERNASIONALE AANGELEENTHEDE THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Martyn Gregory* the author of this report, is a postgraduate research student,at Leicester University in Britain, working on # : thesis, entitled "International Politics of the Conflict in Rhodesia". He recently spent two months in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, : during the pre- and post-election period, as a Research Associate at the University of Rhodesia (now the University of Zimbabwe). He travelled widely throughout the country and interviewed many politicians, officials and military personnel. He also spent two weeks with the South African Institute of International Affairs at Smuts House in Johannesburg. The author would like to thank both, the University of Zimbabwe and the Institute for assistance in the preparation of this report, as well as the British Social Science Research Council which financed his visit to Rhodesia* The Institute wishes to express its appreciation to Martyn Gregory for his co-operation and his willingness to prepare this detailed report on the Zimbabwe elections and their implications for publication by the Institute. It should be noted that any opinions expressed in this report are the responsibility of the author and not of the Institute. FROM RHODESIA TO ZIMBABWE: an analysis of the 1980 elections and an assessment of the prospects Martyn Gregory Contents Introduction .'. Page 1 Paving the way to Lancaster House .... 1 The Ceasefire Arrangement 3 Organization of the Elections (i) Election Machinery 5 (i i) Voting Systems 6 The White Election 6 The Black Election (i) Contesting Parties 7 (ii) Manifestos and the Issues . -

A Critique of Patrick Chakaipa's 'Rudo Ibofu'

Journal of English and literature Vol. 2(1). pp. 1-9, January 2011 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ijel ISSN 2141-2626 ©2011 Academic Journals Review Epistemological and moral implications of characterization in African literature: A critique of Patrick Chakaipa’s ‘Rudo Ibofu’ (love is blind) Munyaradzi Mawere Department of Humanities, Universidade Pedagogica, Mozambique. E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted 26 November, 2010 This paper examines African epistemology and axiology as expressed in African literature through characterization, and it adopts the Zimbabwean Patrick Chakaipa’s novel, Rudo Ibofu as a case study. It provides a preliminary significance of characterization in Zimbabwean literature and by extension African literature before demonstrating how characterization has been ‘abused’ by some African writers since colonialism in Africa. The consequences are that a subtle misconstrued image of Africa can indirectly or directly be perpetuated within the academic settings. The Zimbabwean novel as one example of African literature that extensively employs characterization, it represents Africa. The mode of this work is reactionary in the sense that it is responding directly to trends identifiable in African literature spheres. The paper therefore is a contribution towards cultural revival and critical thinking in Africa where the wind of colonialism in the recent past has significantly affected the natives’ consciousness. In the light of the latter point, the paper provides a corrective to the western gaze that demonized Africa by advancing the view that Africans were without a history, worse still epistemological and moral systems. The paper thus criticizes, dismantles and challenges the inherited colonial legacies which have injured many African scientists and researchers’ consciousness; it is not only against the vestiges of colonialism, but of neo-colonialism and western cultural arrogance that have been perpetuated by some African writers through characterization. -

Africa from the BOTTOM UP

Africa FROM THE BOTTOM UP CITIES, ECONOMIC GROWTH, AND PROSPERITY IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA Founded in 1983, Monitor is a global fi rm that serves clients through a range of professional services — strategic advisory, capability building and capital services — and integrates these services in a customized way for each client. Monitor is focused on helping clients grow in ways that are most important to them. To that end, we offer a portfolio of services to our clients who seek to stay competitive in their global markets. The fi rm employs or collaborates with some of the world’s foremost business experts and thought leaders to develop and deliver specialized capabilities in areas including competitive strategy, marketing and pricing strategy, innovation, national and regional economic competitiveness, organizational design, and capability building. FOR MORE INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT: Christoph Andrykowsky [email protected] tel +27-11-712-7517 Bernard Chidzero, Jr. [email protected] tel +27-11-712-7519 Jude Uzonwanne [email protected] tel +27-11-712-7550 MONITOR GROUP 83 Central Street MONITOR GROUP Houghton Two Canal Park South Africa, 2198 Cambridge, MA 02141 USA tel +27 11 712 7500 tel 1-617 252 2000 fax +27 11 712 7600 fax 1-617 252 2100 www.monitor.com/za www.monitor.com Africa FROM THE BOTTOM UP CITIES, ECONOMIC GROWTH, AND PROSPERITY IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA Executive Summary .............................................................4 Introduction .........................................................................16 Cities as Platforms for Growth ........................................... 22 Pointing the Way: Johannesburg, Lagos, Nairobi, and Dakar ......................... 34 Creating City-Clusters I: Infrastructure .............................. 52 Creating City-Clusters II: Unlocking Human Potential ...... 74 Creating City-Clusters III: Help from Abroad .................... -

The Rhodesian Crisis in British and International Politics, 1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE RHODESIAN CRISIS IN BRITISH AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1964-1965 by CARL PETER WATTS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham April 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis uses evidence from British and international archives to examine the events leading up to Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965 from the perspectives of Britain, the Old Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), and the United States. Two underlying themes run throughout the thesis. First, it argues that although the problem of Rhodesian independence was highly complex, a UDI was by no means inevitable. There were courses of action that were dismissed or remained under explored (especially in Britain, but also in the Old Commonwealth, and the United States), which could have been pursued further and may have prevented a UDI. -

Migration Trajectories and Experiences of Zimbabwean Immigrants in the Limpopo Province of South Africa: Impediments and Possibilities

Migration Trajectories and Experiences of Zimbabwean Immigrants in the Limpopo Province of South Africa: Impediments and Possibilities by Douglas Mpondi, Ph.D. [email protected] Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Africana Studies, Metropolitan State University of Denver Denver, Colorado, USA & Liberty Mupakati, Ph.D. [email protected] Lecturer, Department of Geography and Development Studies, The Catholic University of Zimbabwe Harare, Zimbabwe Abstract Drawing from fieldwork research in Limpopo, South Africa, this paper explored the complexities that surrounded the Zimbabwean emigration to South Africa since the late 1990’s through a series of migration waves and flows. It surveyed the context in which migrants left Zimbabwe and the reasons that drove them into exile and their experiences in South Africa. The paper builds on the narratives from the in-depth interviews and explores in detail the reasons the migrants cited as occasioning their exit. Migration waves from Zimbabwe were driven in part by the political and socio-economic implosion in the country and other complex factors. Zimbabwean emigration into South Africa is highly informalized and perilous. This paper sheds light on the timing of migration episodes and delineates the gender, education, and the skills base of this migrant community. The study of migration is a fiercely contested terrain with a plethora of academic lines of inquiry e.g. voluntary and involuntary migration, skilled and non-skilled migration. 215 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.12, no.1, September 2018 Various studies have demonstrated the utility of transnationalism as a theoretical framework for explaining migration because it provides for participation of prior migrants in perpetuating the migration process once begun. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Ill 1.1C I'mie Ill 1.1C I'mie anJevorto men tI nfm o an Pbity 14AsnRod- % - I-- - LEYLAN Suppliers of Comet Trucks, and Service Parts Leyland (Zimbabwe) Limited Watts Road Southerton Phone: 67861 Telex: 26387 ZW Zimbabwe News Official Organ of ZANU PF CONTENTS Editorial: M eet the people at w ork ......................................................................... 2 Please, don't rem ind us ........................................................................... 2 Letters: Cde. Mutasa's letter in response to an article which appeared in the Horizon (April issue) ......... , ............................................. 3 Local News: People have confidence in ZANU PF - President ..................... ................. 4 President m eets the people ..................................................................... 5 ZANU PF'drafts Code of Conduct................... .............. 6 National: Interview with Cde. Makombe - Democracy prevails in Zimbabwe .............. 8 Social development fund to minimise suffering .......................................... 10 Plan. of action needed to uplift Mt. Darwin - Patel .................................... 12 Fiscal reform s on course - Chidzero ....................................................... 12 ZBC flouted Tender Board Procedure ........ .................... 13 Health: W om an running illegal m edical school ..................................................... 15 Wildlife: The Tim es of London w as incorrect ........................................................... 15 International: -

New Otte New Otte FEBRUARY 1961 Contents World Affairs 2 Britain 5

New otte New otte FEBRUARY 1961 Contents World Affairs 2 Britain 5 South Africa 11 Central Africa 16 Southern Rhodesia 17 Northern Rhodesia 20 Nyasaland 22 Bechuanaland 23 East Africa 24 Kenya 25 Uganda 27 Tanganyika 28 Zanzibar 29 Information Section 30 Published by THE INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS 36 Jermyn Street, London S W 1 World Affairs A New Broom in Washington John Fitzgerald Kennedy became President of the United Stat( January and speedily set about dispelling any complacency oi that might linger in administrative and legislative circles. His ir call to Americans to bear the burden of a 'long twilight struggle the common enemies of mankind: tyranny, poverty, disease itself' was followed by a grimly Churchillian 'State of the address aimed at impressing on his fellow-citizens the extent of I national peril and the national opportunity, at home and Attention was drawn to a forgotten group, the 'poor Am and to the 'denial of constitutional rights to some of our fellov cans on account of race'; to the growing menace of the Cold Asia and Latin America and to the even greater 'challenge of tt that lies beyond the Cold War'. To meet these external chalh advocated increased flexibility and a revision of military, econo political tools, equal attention to be paid to the 'olive branch' 'bunch of arrows'. A new and co-ordinated programme of economic, political and social progress should be establishe national peace corps of dedicated American men and women sI formed to assist in the local execution of this programme. Meanwhile the five-year Civil War centenary programme bel due solemnity at Grant's Tomb in New York and the grave o Virginia. -

NATIONAL HEROES (1St Series) Issued 4Th August, 2005

NATIONAL HEROES (1st Series) Issued 4th August, 2005 (Extracted from Philatelic Bureau Bulletin No 4 of 2005)2 The narrative with the bulletin is, in some instances, very long, below is a short biography of the individuals depicted in this issue. $6,900: Josiah Magama Tongogara. ("Ndugu Tongo") This Hero was bon in 1940, at Shumgwi of humble parents. He died fighting for the liberation of our country on 26 December, 1979, in a road crash in Mozambique, on his way to implement the cease-fire agreement. He joined the National Movement in 1961 as a youth, and was a founder member of ZANU in 1963. In 1967 he became Chairman of the Military committee, and in 1968 he became Chief of Defence in ZANLA High Command, thus successfully prospering the armed struggle. $13,800: Herbert Wiltshire Hamandishe Chitepo Herbert Chitepo was born in Nyanga at Bonda Mission on 5th June 1923 and died in Lusaka, Zambia on the 18th of March 1975 as a result of a car-bomb. He obtained his basic law degree at Fort Hare University (East London), and his admission as a barrister at the Inns of Court (Gray's Inn) in London, England. He became Zimbabwe's first black barrister, stoutly defending the rights of African people. He was appointed director of Public Prosecutions in the newly independent Tanzania, before becoming involved with the liberation movement of Zimbabwe. He eventually become external Chairman of ZANU extraterritorially while many of its leaders were imprisoned inside Rhodesia. His premature death was a great loss to the freedom fighters. -

Re-Living the Second Chimurenga

1-9.fm Page 1 Wednesday, October 26, 2005 4:57 PM FAY CHUNG Re-living the Second Chimurenga Memories from the Liberation Struggle in Zimbabwe With an introduction by Preben Kaarsholm THE NORDIC AFRICA INSTITUTE, 2006 Published in cooperation with Weaver Press 1-9.fm Page 2 Wednesday, October 26, 2005 4:57 PM Indexing terms Biographies National liberation movements Liberation Civil war Independence ZANU Zimbabwe RE-LIVING THE SECOND CHIMURENGA © The Author and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2006 Cover photo: Tord Harlin The Epsworth rocks, Zimbabwe Language checking: Peter Colenbrander ISBN 91 7106 551 2 (The Nordic Africa Institute) 1 77922 046 4 (Weaver Press) Printed in Sweden by Elanders Gotab, Stockholm, 2006 1-9.fm Page 3 Wednesday, October 26, 2005 4:57 PM Dedicated to our children's generation, who will have to build on the positive gains and to overcome the negative aspects of the past. 1-9.fm Page 4 Wednesday, October 26, 2005 4:57 PM 1-9.fm Page 5 Wednesday, October 26, 2005 4:57 PM Contents Introduction: Memoirs of a Dutiful Revolutionary Preben Kaarsholm ................................................................................................................ 7 1. Growing up in Colonial Rhodesia ...................................................... 27 2. An Undergraduate in the ‘60s ............................................................ 39 3. Teaching in the Turmoil of the Townships ................................. 46 4. In Exile in Britain ........................................................................................... -

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 21, No. 3

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 21, No. 3 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuzn199003 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Zimbabwe News, Vol. 21, No. 3 Alternative title Zimbabwe News Author/Creator Zimbabwe African National Union Publisher Zimbabwe African National Union (Harare, Zimbabwe) Date 1990-03-00 Resource type Magazines (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Zimbabwe, South Africa, China, U.S.S.R. Coverage (temporal) 1990 Source Northwestern University Libraries, L968.91005 Z711 v.21 Rights By kind permission of ZANU, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front. Description Editorial. Letters to the Editor. -

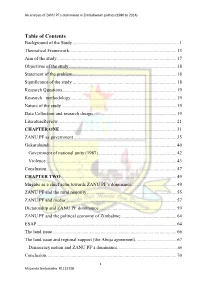

Table of Contents Background of the Study

An analysis of ZANU PF’s dominance in Zimbabwean politics (1980 to 2014) Table of Contents Background of the Study ........................................................................................ 1 Theoratical Framework ......................................................................................... 13 Aim of the study ................................................................................................... 17 Objectives of the study ......................................................................................... 18 Statement of the problem ...................................................................................... 18 Significance of the study ...................................................................................... 18 Research Questions............................................................................................... 19 Research methodology ........................................................................................ 19 Nature of the study .............................................................................................. 19 Data Collection and research design .................................................................... 19 LiteratureReview .................................................................................................. 21 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................. 31 ZANU PF as government .................................................................................... -

Crp 3 B 1 0 0

Studies of revolution generally regard peasant popular support as a prerequisite for success. In this study of political mobilization and organization in Zimbabwe's recent rural-based war of independence, Norma Kriger is interested in the extent to which ZANU guerrillas were able to mobilize peasant support, the reasons why peasants participated, and in the links between the post-war outcomes for peasants and the mobilization process. Hers is an unusual study of revolution in that she interviews peasants and other participants about their experiences, and she is able to produce fresh insights into village politics during a revolution. In particular, Zimbabwean peasant accounts direct our attention to the ZANU guerrillas' ultimate political victory despite the lack of peasant popular support, and to the importance that peasants attached to gender, generational and other struggles with one another. Her findings raise questions about theories of revolution. ZIMBABWE'S GUERRILLA WAR AFRICAN STUDIES SERIES 70 GENERAL EDITOR J.M. Lonsdale, Lecturer in History and Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge ADVISORY EDITORS J.D.Y. Peel, Professor of Anthropology and Sociology, with special reference to Africa, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London John Sender, Faculty of Economics and Fellow of Wolfson College, Cambridge PUBLISHED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE AFRICAN STUDIES CENTRE, CAMBRIDGE A list of books in the series will be found at the end of the volume. ZIMBABWE'S GUERRILLA WAR Peasant Voices NORMA J. KRIGER Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, The Johns Hopkins University Th, tght of he Unt...' V of Cambr-lgc to prt i and sell all mwnn, f bool s He, Vn1tshd hr 14snry' Il s, I.134 The Un-t.s.lq he., printed and jabhshsd o ntnousiy smce 1384.