Number 25B the Cork Fiction Issue 2: Cork Harder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviews of William Wyler's Wuthering Heights

REVIEWS OF WILLIAM WYLER’S WUTHERING HEIGHTS Frank S. Nugent, “Goldwyn Presets Film of 'Wuthering Heights' at Rivoli,” New York Times, April 14, 1939 After a long recess, Samuel Goldwyn has returned to serious screen business again with his film "Wuthering Heights," which had its première at the Rivoli last night. It is Goldwyn at his best, and better still, Emily Brontë at hers. Out of her strange tale of a tortured romance Mr. Goldwyn and his troupe have fashioned a strong and somber film, poetically written as the novel not always was, sinister and wild as it was meant to be, far more compact dramatically than Miss Brontë had made it. During December's dusty researches we expect to be filing it away among the year's best ten; in April it is a living thing, vibrant as the wind that swept Times Square last night. One of the most incredible aspects of it is the circumstance that the story has reached the screen through the agency of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, as un-Brontian a pair of infidels as ever danced a rigadoon upon a classicist's grave. But be assured: as Alexander Woollcott was saying last week, they've done right by our Emily. It isn't exactly a faithful transcription, which would have served neither Miss Brontë nor the screen—whatever the Brontë societies may think about it. But it is a faithful adaptation, written reverently and well, which goes straight to the heart of the book, explores its shadows and draws dramatic fire from the savage flints of scene and character hidden there. -

Mervyn Leroy GOLD DIGGERS of 1933 (1933), 97 Min

January 30, 2018 (XXXVI:1) Mervyn LeRoy GOLD DIGGERS OF 1933 (1933), 97 min. (The online version of this handout has hot urls.) National Film Registry, 2003 Directed by Mervyn LeRoy Numbers created and directed by Busby Berkeley Writing by Erwin S. Gelsey & James Seymour, David Boehm & Ben Markson (dialogue), Avery Hopwood (based on a play by) Produced by Robert Lord, Jack L. Warner, Raymond Griffith (uncredited) Cinematography Sol Polito Film Editing George Amy Art Direction Anton Grot Costume Design Orry-Kelly Warren William…J. Lawrence Bradford him a major director. Some of the other 65 films he directed were Joan Blondell…Carol King Mary, Mary (1963), Gypsy (1962), The FBI Story (1959), No Aline MacMahon…Trixie Lorraine Time for Sergeants (1958), The Bad Seed (1956), Mister Roberts Ruby Keeler…Polly Parker (1955), Rose Marie (1954), Million Dollar Mermaid (1952), Quo Dick Powell…Brad Roberts Vadis? (1951), Any Number Can Play (1949), Little Women Guy Kibbee…Faneul H. Peabody (1949), The House I Live In (1945), Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo Ned Sparks…Barney Hopkins (1944), Madame Curie (1943), They Won't Forget (1937) [a Ginger Rogers…Fay Fortune great social issue film, also notable for the first sweatered film Billy Bart…The Baby appearance by his discovery Judy Turner, whose name he Etta Moten..soloist in “Remember My Forgotten Man” changed to Lana], I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), and Two Seconds (1931). He produced 28 films, one of which MERVYN LE ROY (b. October 15, 1900 in San Francisco, was The Wizard of Oz (1939) hence the inscription on his CA—d. -

Greatest Year with 476 Films Released, and Many of Them Classics, 1939 Is Often Considered the Pinnacle of Hollywood Filmmaking

The Greatest Year With 476 films released, and many of them classics, 1939 is often considered the pinnacle of Hollywood filmmaking. To celebrate that year’s 75th anniversary, we look back at directors creating some of the high points—from Mounument Valley to Kansas. OVER THE RAINBOW: (opposite) Victor Fleming (holding Toto), Judy Garland and producer Mervyn LeRoy on The Wizard of Oz Munchkinland set on the MGM lot. Fleming was held in high regard by the munchkins because he never raised his voice to them; (above) Annie the elephant shakes a rope bridge as Cary Grant and Sam Jaffe try to cross in George Stevens’ Gunga Din. Filmed in Lone Pine, Calif., the bridge was just eight feet off the ground; a matte painting created the chasm. 54 dga quarterly photos: (Left) AMpAs; (Right) WARneR BRos./eveRett dga quarterly 55 ON THEIR OWN: George Cukor’s reputation as a “woman’s director” was promoted SWEPT AWAY: Victor Fleming (bottom center) directs the scene from Gone s A by MGM after he directed The Women with (left to right) Joan Fontaine, Norma p with the Wind in which Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) ascends the staircase at Shearer, Mary Boland and Paulette Goddard. The studio made sure there was not a Twelve Oaks and Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) sees her for the first time. The set single male character in the film, including the extras and the animals. was built on stage 16 at Selznick International Studios in Culver City. ight) AM R M ection; (Botto LL o c ett R ve e eft) L M ection; (Botto LL o c BAL o k M/ g znick/M L e s s A p WAR TIME: William Dieterle (right) directing Juarez, starring Paul Muni (center) CROSS COUNTRY: Cecil B. -

William Wyler & Wuthering Heights

William Wyler & Wuthering Heights: Facts 1. The director William Wyler won Academy Awards for Ben-Hur, The Best Years of Our Lives, and Mrs. Miniver; only John Ford has won more Academy Awards (four). Wyler was nominated for twelve Academy Awards, more than any other director. 2. The Directors Guild of American awarded him a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1966, an Outstanding Directorial Achievement for Ben Hur (1960), and five more nominations for that award. 3. Fourteen actors received Academy Award nominations in Wyler films, which remains a Hollywood record. 4. Laurence Olivier found himself becoming increasingly annoyed with William Wyler's exhausting style of film-making. After yet another take, he is said to have exclaimed, "For God's sake, I did it sitting down. I did it with a smile. I did it with a smirk. I did it scratching my ear. I did it with my back to the camera. How do you want me to do it?" Wyler retorted, "I want it better." 5. Olivier: "If any film actor is having trouble with his career, can't master the medium and, anyway, wonders whether it's worth it, let him pray to meet a man like William Wyler. Wyler was a marvelous sneerer, debunker; and he brought me down. I knew nothing of film acting or that I had to learn its technique; it took a long time and several unhandsome degrees of the torture of his sarcasm before I realized it." 6. Wyler’s daughter Cathy, born in 1939, was named after Cathy in Wuthering Heights. -

I “Weani^^N M'i Ii I JUMW

Constance Clay.” Miss Bennett's more re- Murder Murdered Signs cent screen appearances were In Cycle Constance Bennett has signed a “Topper,” "Merrily We Live,” long-term contract with Columbia “Topper Takes A Trip” and “Tail Some Bad Dramas Pictures. This marks Miss Ben- Spin.”* By nett’s return to the screen after OP MAY 26 _WEIK J_ SUNDAY_MONDAY_ TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY an absence of several months dur- which was Broadway’s Newest Academy "Four Wlvei" "Four Wives" "The Frlvate Lives of "pe Private Live* of "Main Street Lawyer” “Main Street Lawyer" "The Covered Trailer" ing she appearing on __ Ellaabeth and Essex Bliaabeth and laeex” Mystery Play, 17™'.' _H „„ *nd, and “Smaahln* the and “Smashing the and the stage. Sth and Q Sts. 8.E _Mercy Plane._ _Mercy_Plane.J_ and Nt^Place to Go. and “No Place to Oo." __Money Ring," _Money Ring." “Haunted Gold." ‘At the Miss Bennett made her screen Stroke of Eight,’ the Third Ambassador ^2d JtSSBEJ, W8 *.nd James Cagney and Jamei Cagney and- VlrginlaBruce and vIrslnia~Bruce and- Ann Sheridan ln Ann Sheridan In Dennis Morean In Dennis Moraan In debut in “Cytharea." Her first IStni«fh andum Columbiae-nin^ihi* Rd.■><• Torrid !.n Torrid ?.n A,2J? }n Not Met Too Zone._ Zone.___TorrldZone.;_ Tottld Zone. 'Torrid Zone." "Plight Angela." "Might Angela." starring role was in "Sally, Irene Happily AdoIIo Walt Disney'* Walt Disney’* Mlekay Rooney Mickey Rooney Ann Sheridan and ‘Ann Sheridan and "Light of the Western and Some of her "Pinocchio.” "Pinocchio." *“ In Jeffrey Lynn In Jeffrey Lynn in Stera" and "Mve Llt- Mary.’’ many TOta«* Hh St.at n ■ Tom _. -

Merle Oberon, 68, Star of Films Including Wuthering Heights' 2

2/12/2019 Merle Oberon, 68, Star of Films Including Wuthering Heights’ - The New York Times https://nyti.ms/1RRLdkd ARCHIVES | 1979 Merle Oberon, 68, Star of Films Including Wuthering Heights’ By WOLFGANG SAXON NOV. 24, 1979 About the Archive This is a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive, before the start of online publication in 1996. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them. Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcription errors or other problems. Please send reports of such problems to [email protected]. Merle Oberon, the hauntingly beautiful star of “Wuthering Heights” and more than 30 other films, died yesterday afternoon at Cedars‑Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles after having suffered a stroke at her Malibu, Calif., home late Thursday. She was 68 years old. A diminutive 5 feet 2 inches tall, Miss Oberon was of an almost exotic beauty, with perfect skin, dark hair and a slight slant to her eyes that was further accentuated by makeup. Miss Oberon also was well remembered from such other movie hits of long ago as “The Private Life of Henry VIII,” which began her career in 1932; “Dark Angel” and “The Scarlet Pimpernell.” In fact, her screen career, first in England and later in Hollywood, extended into the 1970's, but it was her portrayal of Cathy that comes to mind first when considering her qualities for stardom. “Wuthering Heights,” which remains part of the movie fare on late‑night television, was adapted by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur from Emily Bronte's novel, directed by William Wyler and produced by Samuel Goldwyn. -

Merle Oberon: She Walked in Beauty … Page 1 of 5

Senses of Cinema – Merle Oberon: She walked in beauty … Page 1 of 5 CURRENT ISSUE ABOUT US LINKS TOP TENS GREAT DIRECTORS SPECIAL DOSSIERS WORLD POLLS ARCHIVE CONTACT US DONATIONS ← Previous Post Next Post → Search Merle Oberon: She walked in beauty … SUBSCRIBE by Brian McFarlane September 2009 Feature Articles, Issue 52 Name: Email: Perhaps it was a matter of being caught young. I first saw Merle Register Oberon when I was about 12 or 13 and A Song to Remember (Charles Vidor, 1945) came to rural Victoria some years after a Features Editor: Rolando Caputo Festival Reports Editor: Michelle Carey very long run at Melbourne’s Savoy Theatre. I have never Book Reviews Editor: Wendy Haslem forgotten how she looked in that, and every time I’ve seen it Cteq Annotations & Australian Cinema Editor: Adrian since it brings back that indelible, life-changing image she Danks imprinted on my young mind. Hers was a face of great delicacy, Webmaster and Administrator: Rachel Brown exquisitely oval, framed with lustrous dark hair, with eloquent Social Media Editor: Hayley Inch eyes and bright red lips – and she was unforgettably dressed in pale grey trousers, scarlet waistcoat, generous bow-tie, black cutaway coat and grey top hat on first appearance. As novelist IN THIS ISSUE… George Sand, she swung down a Parisian street (that’s Paris, Hollywood) with ‘friend’ Liszt (Stephen Bekassy), and came into Welcome to Issue 66 of our journal a café where Chopin (Cornel Wilde) and his mentor-teacher, Professor Elsner (Paul Muni), sat at a table. She said little in this scene, but as she and Liszt move on to their own table she inclined her head to look Features provocatively at Wilde to say, “I hope you will like Paris, Monsieur Chopin. -

Mixed Race Capital: Cultural Producers and Asian American Mixed Race Identity from the Late Nineteenth to Twentieth Century

MIXED RACE CAPITAL: CULTURAL PRODUCERS AND ASIAN AMERICAN MIXED RACE IDENTITY FROM THE LATE NINETEENTH TO TWENTIETH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Stacy Nojima Dissertation Committee: Vernadette V. Gonzalez, Chairperson Mari Yoshihara Elizabeth Colwill Brandy Nālani McDougall Ruth Hsu Keywords: Mixed Race, Asian American Culture, Merle Oberon, Sadakichi Hartmann, Winnifred Eaton, Bardu Ali Acknowledgements This dissertation was a journey that was nurtured and supported by several people. I would first like to thank my dissertation chair and mentor Vernadette Gonzalez, who challenged me to think more deeply and was able to encompass both compassion and force when life got in the way of writing. Thank you does not suffice for the amount of time, advice, and guidance she invested in me. I want to thank Mari Yoshihara and Elizabeth Colwill who offered feedback on multiple chapter drafts. Brandy Nālani McDougall always posited thoughtful questions that challenged me to see my project at various angles, and Ruth Hsu’s mentorship and course on Asian American literature helped to foster my early dissertation ideas. Along the way, I received invaluable assistance from the archive librarians at the University of Riverside, University of Calgary, and the Margaret Herrick Library in the Beverly Hills Motion Picture Museum. I am indebted to American Studies Department at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa for its support including the professors from whom I had the privilege of taking classes and shaping early iterations of my dissertation and the staff who shepherded me through the process and paperwork. -

Queenie: Smudging the Distinctions Between Black and White

QUEENIE: SMUDGING THE DISTINCTIONS BETWEEN BLACK AND WHITE Mark Haslam On Sunday May 10, 1987 and Monday May 11, 1987, ABC Television in the United States aired a two-part made-for-TV movie named Queenie. Queenie is a rare example of the treatment of Anglo-Indians in popular film, television, or in this case a film made for television. The film is based on a book, by the same name, by Michael Korda. Korda’s book is structured on the life of his aunt and Hollywood legend Merle Oberon, who is widely considered to have been Anglo-Indian. This paper investigates the text and context of Queenie in light of Ella Shohat’s assertion that: "ethnicity and race inhere in virtually all film, not only in those where ethnic issues appear on the "epidermic" surface of the text." In brief, an Anglo-Indian is anyone of European descent in the male line who is of mixed European and Indian blood. I myself am an Anglo-Indian, born and raised in Calcutta, India. I have also been involved in image-making and history-telling of the Anglo-Indian community, primarily through a television documentary that aired on national television in Canada in 1992-93. These significant experiences help frame my reading of Queenie. Firstly, I frame my reading of the film through my familiarity with some of the oral history of the community and some of the historical literature. Secondly, I frame my reading through my own experience of living as an Anglo- Indian - relating to others within and outside of my community; and at different points in time internalizing the stereotypes or fighting against them. -

R,Fay 16 2013 Los Angeles City Council Room 395, City Hall 200 North Spring Street, Room 410 Los Angeles, California 90012

DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING EXECUTIVE OFFICES OFFICE OF HISTORIC RESOURCES MICHAEL LOGRANDE 200 N. SPRING STREET. ROOM 620 CITY OF Los ANGELES los ANGELES,CA 90012·4801 DIRECTOR (213) 978 ·1200 CALIFORNIA (213) 978·1271 ALAN BELl, Arc? CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION O,PUlY D1R'CTOR· (213) 978-1272 RICHARD BARRON PR,S!O~NT USA WEBBER, Ale!> ROELLA H. LOUIE DEPUTY DIRECTOR VlCE-PR,SIOENT (213) 978-1274 TARA}. HAMACHER GAlL KENNARD EVA YUAN-MCDANrEl OZSCOTT DEPUlY DIRECTOR ANTONIO R. VILLARAIGOSA (213) 978-1273 FElY C PINGOl MAYOR FAX: (213) 978-1275 COMMISSION iOXECUTIVE ASSISTANT (213) 978-1294 INFORMATION (213) 978·1270 wwwplanning.ladty.org Date: r,fAY 16 2013 Los Angeles City Council Room 395, City Hall 200 North Spring Street, Room 410 Los Angeles, California 90012 Attention: Sharon Gin, Legislative Assistant Planning and Land Use Management Committee CASE NUMBER: CHCw2013w510wHCM GIBBONSwDEL RIO RESIDENCE 757 KINGMAN AVENUE At the Cultural Heritage Commission meeting of May 9, 2013, the Commission moved to include the above property in the list of Historic-Cultural Monument, subject to adoption by the City Council. As required under the provisions of Section 22.171.10 of the Los Angeles Administrative Code, the Commission has solicited opinions and information from the office of the Council District in which the site is located and from any Department or Bureau. of the city whose operations may be affected by the designation of such site as a Historic-Cultural Monument. Such designation in and of itself has no fiscal impact Future applications for permits may cause minimal administrative costs. -

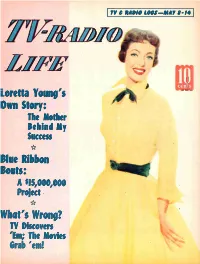

Tomeof a $15,000,000 Project

TV & RADIO LOGS-MAY S-14 Loretta Young's Own Story: The Mother Behind My Success Blue Ribbon Bouts: tomeof A $15,000,000 Project What's Wrong? TV Discovers 'Em; The Movies Grab 'em! fe INSPIRE THE PEN Mrs. Renzo Dare, Fontana experience that the ones who write about the Lord loving the common To the person who says she doesn't in are regulars who try to get on people because he made so many of like the Pallais Sisters on "Western every quiz show and do not make the them—is true. Attending the Liberace Varieties," all Ican say is she doesn't grade. In fact I never knew there concert in Pasadena it was interest- know good entertainment when she were so many jealous people until I ing to see how people really love him started going to the broadcasts. hears it and sees it, so let her turn —and he loves to play. He gives the KABC is one of the few studios that her dial. For me, the Pallais Sisters public what they want and is sin- are the best part of "Western tries to do anything about it, and they penalized some very nice people cerely grateful for his good fortune. Varieties." If it wasn't for them I He is so big hearted I imagine he wouldn't even tune in the show. on account of a few who thought they had special rights to be on every pro- would even hand out beans to starv- gram. ing critics. He won't be needing hand- Michael J. -

Puttin' on the Glitz: Hollywood's Influence on Fashion

SPRING EXHIBIT | LANGSON LIBRARY Puttin' on the Glitz Hollywood's Influence o n Fashion OCTOBER 2010 - APRIL 2011 MURIEL ANSLEY REYNO- 1 -LDS EXHIBIT GALLERY Puttin’ on the Glitz Hollywood’s Influence on Fashion An exhibit in the UC Irvine Langson Library Muriel Ansley Reynolds Exhibit Gallery October 2010 - April 2011 Curated by Becky Imamoto, Research Librarian for History THE UC IRVINE LIBRARIES • IRVINE, CALIFORNIA • 2010 Welcome to the UCI Libraries’ Fall 2010 exhibition. Puttin’ on the Glitz: Hollywood’s Influence on Fashion examines the major impact that Hollywood had and continues to have over fashion. This exciting exhibit highlights films and designers from Hollywood’s golden years through the 20th century, all presented within a historical context. Items on display include significant books, journals, images, videos, and movie posters from the Libraries’ collections, and stunning costumes from UCI’s drama department. The curator is Becky Imamoto, Research Librarian for History. I hope you enjoy the exhibit and return to view others in the future. Gerald L. Lowell Interim University Librarian - 3 - this exhibit examines the history of Hollywood costume design from its inception to the end of the 20th century. In the early 1910s, costume design was little more than an afterthought, with silent screen actresses providing costumes from their personal wardrobes. However, during the Golden Age (1930- 1959), Hollywood realized how much publicity and money could be generated through its promotion of new fashion designs, and so set to work building an image of splendor, luxury, and endless consumption. Hollywood was, and is, a powerful social force that determines what is considered by the rest of the world to be beautiful and glamorous.