Puttin' on the Glitz: Hollywood's Influence on Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Malpaso Dance Company Is Filled with Information and Ideas That Support the Performance and the Study Unit You Will Create with Your Teaching Artist

The Joyce Dance Education Program Resource and Reference Guide Photo by Laura Diffenderfer The Joyce’s School & Family Programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council; and made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. Special support has been provided by Con Edison, The Walt Disney Company, A.L. and Jennie L. Luria Foundation, and May and Samuel Rudin Family Foundation, Inc. December 10, 2018 Dear Teachers, The resource and reference material in this guide for Malpaso Dance Company is filled with information and ideas that support the performance and the study unit you will create with your teaching artist. For this performance, Malpaso will present Ohad Naharin’s Tabla Rasa in its entirety. Tabula Rasa made its world premiere on the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre on February 6, 1986. Thirty-two years after that first performance, on May 4, 2018, this seminal work premiered on Malpaso Dance Company in Cuba. Check out the link here for the mini-documentary on Ohad Naharin’s travels to Havana to work with Malpaso. This link can also be found in the Resources section of this study guide. A new work by company member Beatriz Garcia Diaz will also be on the program, set to music by the Italian composer Ezio Bosso. The title of this work is the Spanish word Ser, which translates to “being” in English. I love this quote by Kathleen Smith from NOW Magazine Toronto: "As the theatre begins to vibrate with accumulated energy, you get the feeling that they could dance just about any genre with jaw-dropping style. -

At Home with the Movies

At Home with the Movies PAT COSTA THE BOBO (1967) Friday, May 26 (NBC) He plays a Russian-British Thursday, May 25 (CBS) double agent and Mia Farrow is The regular Friday night NBC the love interest, naturally. The As I A poorly-done comedy starring movie is. pre-empted this night best parts are taken by Tom Peter Sellers, this is about an ex- for Chronolog, the documentary Courtenay, Per Oscarsson and matador from Barcelona who de series that everyone says they Lionel Stander in supporting cides to become a singer and se watch when pollsters call to ask roles.- See It duce a high-class prostitute which programs are being played by Britt Ekland. viewed. It was rated A-3, unobjection able for adults, by the national Rossano Brazzi and Adolfo Catholic film office. Celi are lost in supproting roles. TOPAZ (1970) Those who watched the televi supporting awards for their The national Catholic film of Saturday, May 27 sion industry present itself a- work on "The Mary Tyler Moore fice rated this A-3, unobjection wards for 2'/s hours recently at A foreign-intrigue adventuite THE SINGING NUN (1966) Show", gave extended credit able "for adults. Monday, May 29 (NBC) the 24th annual Emmy show to the writers on that situation drama, this one uses the Cuban could have learned a lot about comedy, which is one of the best missile crisis as its launching A syrupy concoction starring this medium. written fun shows of ail time. Gabrielli pad, with John Forsyth the only Debbie Reynolds as a constantly jiame in the cast that hops from cheerful nun who manages a rec And probably the first lesson Lesson three could deal with Speaks in country to country in this politi ord contract in between serving was that TV knows no more another background job so cal cloak and dagger film. -

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Film and Video 1 Audio 3 Printed Material 5 Professional Material 10 Correspondence 13 Financial Material 50 Manuscripts 50 Photographs 51 Personal Memorabilia 65 Scrapbooks 67 Fontaine, Joan #570 Box 1 No Folder I. Film and Video. A. Video cassettes, all VHS format except where noted. In date order. 1. "No More Ladies," 1935; "Tell Me the Truth" [1 tape]. 2. "No More Ladies," 1935; "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937; "Maid's Night Out," 1938; "The Selznick Years," 1969 [1 tape]. 3. "Music for Madam," 1937; "Sky Giant," 1938; "Maid's Night Out," 1938 [1 tape]. 4. "Quality Street," 1937. 5. "A Damsel in Distress," 1937, 2 copies. 6. "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937. 7. "Maid's Night Out," 1938. 8. "The Duke ofWestpoint," 1938. 9. "Gunga Din," 1939, 2 copies. 10. "The Women," 1939, 3 copies [4 tapes; 1 version split over two tapes.] 11. "Rebecca," 1940, 3 copies. 12. "Suspicion," 1941, 4 copies. 13. "This Above All," 1942, 2 copies. 14. "The Constant Nymph," 1943. 15. "Frenchman's Creek," 1944. 16. "Jane Eyre," 1944, 3 copies. 2 Box 1 cont'd. 17. "Ivy," 1947, 2 copies. 18. "You Gotta Stay Happy," 1948. 19. "Kiss the Blood Off of My Hands," 1948. 20. "The Emperor Waltz," 1948. 21. "September Affair," 1950, 3 copies. 22. "Born to be Bad," 1950. 23. "Ivanhoe," 1952, 2 copies. 24. "The Bigamist," 1953, 2 copies. 25. "Decameron Nights," 1952, 2 copies. 26. "Casanova's Big Night," 1954, 2 copies. -

Spring 2021 Mayberry Magazine

Spring 2021 MayberryMAGAZINE Mayberry Man Andy Griffith Show Movie nearing release A star comes to visit Andy Finds Himself Mayberry Trivia College opened new Test your knowledge world What’s Happening? Comprehensive calendar ISSUE 30 Table of Contents Cover Story — Finally here? Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, work on the much ballyhooed Mayberry Man movie has continued, working around delays, postponements, and schedule changes. Now, the movie is just a few months away from release to its supporters, and hopefully, a public debut not too long afterward. Page 8 Andy finds himself He certainly wasn’t the first student to attend the University of North Carolina, nor the last, but Andy Griffith found an outlet for his creative talents at the venerable state institution, finding himself, and his career path, at the school. Page 4 Guest stars galore Being a guest star on “The Andy Griffith Show” could be a launching pad for young actors, and even already established stars sometimes wanted the chance to work with the cast and crew there. But it was Jean Hagen, driving a fast car and doing some smooth talking, who was the first established star to grace the set. Page 6 What To Do, What To Do… The pandemic put a halt to many shows and events over the course of 2020, but there might very well be a few concerts, shows, and events stirring in Mount Airy — the real-life Mayberry — this spring and summer. Page 10 SPRING 2021 SPRING So, You Think You Know • The Andy Griffith Show? Well, let’s see just how deep your knowledge runs. -

819 PR Kit Pages

Media Contact: Liz Bodet 504-583-5550 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Broussard’s Family Tree.............................................................................. 1 Cocktails Through the Decades...................................................................... 2 Coffee Menu......................................................................................... 3 Spice Menu.......................................................................................... 4 Rice Menu........................................................................................... 5 Pecan Menu.......................................................................................... 6 Citrus Menu: Reveillon............................................................................... 7 819 RUE CONTI | 504.581.3866 | BROUSSARDS.COM As Broussard’s commemorates 100 years of fine dining, we also celebrate our native foods and traditions that share the same rich history as our grande dame restaurant. Louisiana’s hot, humid summers and short, mild winters allow for a variety of sweet citrus to be grown and then harvested in late fall or early winter, just in time for Reveillon. Chef Jimi Setchim showcases Louisiana citrus with several special menu items on the traditional Reveillon menu. “Walk through any neighborhood in New Orleans and you’ll pass countless citrus trees. Some sprouted up on their own long ago. Some were planted by home gardeners because of how well they grow in Louisiana. All of them are stunning— the rich green leaves, -

"Hello, Dolly!" at Auditorium Theatre, Jan. 27

AUDITORIUM THEATRE ROCHESTER JANUARY 27 BROAD'lMAY TO FEBRUARY 1 THEATRE LEAGUE 1969 YVONNE DECARLO m HELLO, gOLL~I llng1na1ly D1rected and ChoreogrJphPd by GOWER CHDIPIOII Th1s Pr oductiOn D1rected by LUCIA VICTOR ~tenens FEATURING OUR SATURDAY NITE SPECIAL Prime Rib of Beef Au Jus Baked Potato with Sour Cream & Chives Vegetable - Salad - Coffee $3.95 . ALSO MANY OTHER DELICIOUS ITEMS Stop in for dinner before the show or after the show for a late evening anack SERVING 7 DAYS & NITES FROM 11 A.M. till 2 A.M. 1501 UNIVERSITY AVE . EXTENSION PLENTY OF FlEE PAIICING For Reservations Call: 271-9635 or 271-9494 PARTY AND BANQUET ACCOMMODATIONS Consult Us For Your Banquets And Part i es . • • we w i ll be glad to hove you . Wm. Fisher, Budd Filippo & Ken Gaston proudly present YVONNE DE CARLO in The New York Critics Circle & Tony Award Winn1ng Mus1cal "HELLO, DOLLVI 11 Book IJy Music & Lyrics by MICHAEL STEW ART JERRY HERMAN Based on the originc~l play by Thornton Wilder also starring DON DE LEO with Kathleen Devine George Cavey Rick Grimaldi Suzanne Simon David Gary Althea Rose Edie Pool Norman Fredericks Settings Designed by Lighting Consultant Costumes by Oliver Smith Gerald Richland freddy Wittop Dance & Incidental Music Orchestration by Arrangements by Musical Dirt!cliun by Phillip J. Lang Peter Howard Gil Bowers [)ances Staged for this Production hy Jack Craig Original Choreography & Direction by GOWER CHAMPION This Production Staged by Lucia Victor PHIL'S PANTRYS J A Y ' S "REAL DELICATESSENS" Fresh Sliced Cold Meats D I N E R Home Made Salads & Baked Beans lWO LOCAnONS 2612 W. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Kümtür Emperyalizmi Ve Küfeseg~Esme(*L .:O

, Küresel Hollywood (Global Hollywood): thınrNood tarihi kümtür emperyalizmi ve kÜfeseg~esme(*l .:o Çeviri: Ayşegül Gürsoy - Mehmet OIcay Toby MiIler ;* ı.- § $1*&.* döbeNe e Kültü, emperyalizmi, çoğunlukla solcu analizIe kudurtacak keder edepli - arzu, fantezi, korku, çekicilik ile yüklü özdeşleştirilen bir bakıŞ QÇ1sldır ... ve bu yüzden genellikle ciddi olarak bir terim, tasvir edilmesi gereken şey için ise entelektüel bir ele alınmaz ... (Çünkü bu bahş açısı, güya) dünya yurttaşlannın, belirsizlik. "Hollywood", ister solcu, ister sağa ya da ister küresel reklamalığın ve Amerikan televizyonunun mesajlamıa hırşı üçüncü yolcu olsun, küreselleşmenin etkilerine dair neredeyse direnç gösferebileceklerini veya bu mesajlan kendilerine göre tüm tasvirlerde, suyun yUzeyindeki bir gösterge gibi, ABD'nin uyarlııyabilecekleri.ni göz ardı eder; daluısı Jrü.ltü,el olarak hayatta dünyanın kapitalist dönüşürnu için yürüttfığü başanh haçlı \ kalabilmeye dair endişelerin de, sadece büyük güçlerle kendi sınır/ım seferinin ekonomik yangınlanndan yükselen bir nevi kültürel i dahilindeki etnikazınlıklara karşı ulus devletlerin siyasaları duman olarak ortaya konur. Hollywood'un iktisadi küreselleş tarafindan kışkırtıldığını varsayar. Uohn H. Dawning, 1996) menin başlıca kamb olduğu biçi.ınindeki bu zayıf tasviri tartış malıyız, çünkü bu yaklaşım, Hollywood'un, küreselleşme 1 süreçini hem canlandıranhem de onun tarafından canlandırıJan Çoğunluk tarafından, Eric Hobsbawm'ın sözleriyle "Birleşik yapısı dolayısıyla, çağdaş siyasal iktisat a9sından taşıdığı kritik De'\lletler'in ve yaşam tarzının küresel zaferi" olarak anlaşılan önemi teslim etmekte yetersiz kalıyor. Kapitalist yayılmanın şu bir momentte yaşıyoruz. Çok başka bir perspektiften bakan anki evresinde Hollywood'u tüm diğer endüstrilerden ayıran Henry Kissinger, "Küreselleşme, Birleşik Devletler'in egemen şey, onun Yeni Uluslararası Kültürel İşbölümü'ne (New rolünün diğer adıdır" diyecek kadar ileri gidiyor. Kendi danı.ş 1 International Division of Culhıral Labour) komuta etmesidir. -

Puvunestekn 2

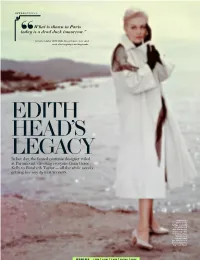

1/23/19 Costume designers and Illustrations 1920-1940 Howard Greer (16 April 1896 –April 1974, Los Angeles w as a H ollywood fashion designer and a costume designer in the Golden Age of Amer ic an cinema. Costume design drawing for Marcella Daly by Howard Greer Mitc hell Leis en (October 6, 1898 – October 28, 1972) was an American director, art director, and costume designer. Travis Banton (August 18, 1894 – February 2, 1958) was the chief designer at Paramount Pictures. He is considered one of the most important Hollywood costume designers of the 1930s. Travis Banton may be best r emembered for He held a crucial role in the evolution of the Marlene Dietrich image, designing her costumes in a true for ging the s tyle of s uc h H ollyw ood icons creative collaboration with the actress. as Carole Lombard, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae Wes t. Costume design drawing for The Thief of Bagdad by Mitchell Leisen 1 1/23/19 Travis Banton, Travis Banton, Claudette Colbert, Cleopatra, 1934. Walter Plunkett (June 5, 1902 in Oakland, California – March 8, 1982) was a prolific costume designer who worked on more than 150 projects throughout his career in the Hollywood film industry. Plunk ett's bes t-known work is featured in two films, Gone with the Wind and Singin' in the R ain, in which he lampooned his initial style of the Roaring Twenties. In 1951, Plunk ett s hared an Osc ar with Orr y-Kelly and Ir ene for An Amer ic an in Paris . Adr ian Adolph Greenberg ( 1903 —19 59 ), w i de l y known Edith H ead ( October 28, 1897 – October 24, as Adrian, was an American costume designer whose 1981) was an American costume designer mos t famous costumes were for The Wiz ard of Oz and who won eight Academy Awards, starting with other Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and The Heiress (1949) and ending with The Sting 1940s. -

Signed, Sealed and Delivered: ''Big Tobacco'' in Hollywood, 1927–1951

Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.2008.025445 on 25 September 2008. Downloaded from Research paper Signed, sealed and delivered: ‘‘big tobacco’’ in Hollywood, 1927–1951 K L Lum,1 J R Polansky,2 R K Jackler,3 S A Glantz4 1 Center for Tobacco Control ABSTRACT experts call for the film industry to eliminate Research and Education, Objective: Smoking in movies is associated with smoking from future movies accessible to youth,6 University of California, San Francisco, California, USA; adolescent and young adult smoking initiation. Public defenders of the status quo argue that smoking has 10 2 Onbeyond LLC, Fairfax, health efforts to eliminate smoking from films accessible been prominent on screen since the silent film era California, USA; 3 Department of to youth have been countered by defenders of the status and that tobacco imagery is integral to the artistry Otolaryngology – Head & Neck quo, who associate tobacco imagery in ‘‘classic’’ movies of American film, citing ‘‘classic’’ smoking scenes Surgery, Stanford University with artistry and nostalgia. The present work explores the in such films as Casablanca (1942) and Now, School of Medicine, Stanford, 11–13 California, USA; 4 Center for mutually beneficial commercial collaborations between Voyager (1942). This argument does not con- Tobacco Control Research and the tobacco companies and major motion picture studios sider the possible effects of commercial relation- Education and Department of from the late 1920s through the 1940s. ships between the motion picture and tobacco Medicine, -

Final J.Min |O.Phi |T.Cun |Editor |Copy

Style SPeCIAl What is shown in Paris today is a dead duck tomorrow.” — Costume designer EDITH HEAD, whose 57-year career owed “ much of its longevity to avoiding trends. C Edith Head’s LEgacy In her day, the famed costume designer ruled at Paramount, dressing everyone from Grace Kelly to Elizabeth Taylor — all the while savvily getting her way By Sam Wasson Kim Novak’s wardrobe for Vertigo, including this white coat with black scarf, was designed to look mysterious. “This girl must look as if she’s just drifted out of the San Francisco fog,” said Head. FINAL J.MIN |O.PHI |T.CUN |EDITOR |COPY Costume designer edith head — whose most unforgettable designs included Grace Kelly’s airy chiffon skirt in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, Gloria Swanson’s darkly elegant dresses in Sunset Boulevard, Dorothy Lamour’s sarongs, and Elizabeth Taylor’s white satin gown in A Place in the Sun — sur- vived 40 years of changing Hollywood styles by skillfully eschewing fads of the moment and, for the most part, gran- Cdeur and ornamentation, too. Boldness, she believed, was a vice. Thirty years after her death, Head is getting a new dose of attention. A gor- geous coffee table book,Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer, was recently published. And in late March, an A to Z adapta- tion of Head’s seminal 1959 book, The Dress Doctor, is being released as well. ! The sTyle setter of The screen The breezy volume spotlights her trade- Clockwise from above: 1.