“Long Held Secrets of Karate Revealed”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Christian' Martial Arts

MY LIFE IN “THE WAY” by Gaylene Goodroad 1 My Life in “The Way” RENOUNCING “THE WAY” OF THE EAST “At the time of my conversion, I had also dedicated over 13 years of my life to the martial arts. Through the literal sweat of my brow, I had achieved not one, but two coveted black belts, promoting that year to second degree—Sensei Nidan. I had studied under some internationally recognized karate masters, and had accumulated a room full of trophies while Steve was stationed on the island of Oahu. “I had unwittingly become a teacher of Far Eastern mysticism, which is the source of all karate—despite the American claim to the contrary. I studied well and had been a follower of karate-do: “the way of the empty hand”. I had also taught others the way of karate, including a group of marines stationed at Pearl Harbor. I had led them and others along the same stray path of “spiritual enlightenment,” a destiny devoid of Christ.” ~ Paper Hearts, Author’s Testimony, pg. 13 AUTHOR’S NOTE: In 1992, I renounced both of my black belts, after discovering the sobering truth about my chosen vocation in light of my Christian faith. For the years since, I have grieved over the fact that I was a teacher of “the Way” to many dear souls—including children. Although I can never undo that grievous error, my prayer is that some may heed what I have written here. What you are about to read is a sobering examination of the martial arts— based on years of hands-on experience and training in karate-do—and an earnest study of the Scriptures. -

HARDSTYLE 2 2004 Spring

Kettlebells, Bruce Lee and the Power of Icons When I first met Pavel at a stretching Explosive power. And almost mystical “I want to be like Bruce” workshop in Minneapolis, in early 1997, I strength gains (the notorious What the Hell? was immediately struck by his charismatic effect). For women, a toned, firm, strong Images can lodge in our brains and become ability to model and convey a stunning shape that enhances the best of the female an ideal that drives us forward. combination of strength and flexibility. Pavel body. For both genders, greater energy, cut through the BS in startling fashion, to higher self-esteem and greater sense of As a young man, in the seventies, Bruce Lee give you what really works. Just like Bruce… overall well being. had that impact on me. The classic image of Bruce—his ripped-to-shreds chest decorated Later that year Dragon Door published All delivered by one compact, portable with claw marks, posing in steely-sinewed, Pavel’s first book, Beyond Stretching, device, in just minutes a day… martial defiance—became my iconic followed by Beyond Crunches, the landmark inspiration for physical excellence. classic Power to the People! and finally, The Russian Kettlebell Challenge in 2001. And Physically, I wanted “to be like Bruce.” the fitness landscape in America changed And, of course Bruce influenced and inspired forever. Bruce Lee + Kettlebells millions like me to jump into martial 2 training and emulate his example. = Iconic Power What does Bruce Lee embody as an iconic And what better testimony to the iconic ideal? Raw, explosive power. -

Pine Waves Newsletter Vol 10 Iss 1

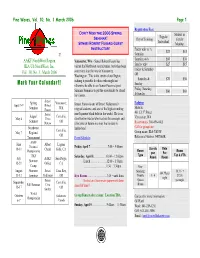

Pine Waves, Vol. 10, No. 1 March 2006 Page 1 Registration Fees: Don’t Miss the 2006 Spring Student or Regular Seminar! Day of Training Family Individual Sensei Robert Fusaro Guest Member Instructor! Friday only or ½ $25 $15 Saturday © Saturday only $50 $30 AAKF NorthWest Region Vancouver, WA – Sensei Robert Fusaro has JKA-US NorthWest, Inc. visited the Northwest several times, but it has been Sunday only $25 $15 Friday & Saturday Vol. 10, No. 1, March 2006 some time since he was in Vancouver, OR Washington. This is the center of our Region, making it possible for those who might not Saturday & $70 $50 Mark Your Calendar!! otherwise be able to see Sensei Fusaro at past Sunday Friday, Saturday, Summer Seminars to get the opportunity to attend $80 $60 & Sunday his classes. Spring Sensei Vancouver, Lodging April 7-9 Robert Sensei Fusaro is one of Sensei Nishiyama’s Seminar WA Shilo In Fusaro original students, and one of the highest ranking th non-Japanese black belts in the world. He is an 401 E 13 Street Judges’ Sensei Corvallis, May 6 Vince excellent instructor who teaches the concepts and Vancouver, WA Seminar OR Nistico principles of karate in a way that is easy to Reservations: 360-696-0411 Northwest understand. Call for group rate: Corvallis, May 7 Regional Group name: JKA-USNW OR Tournament Event Schedule Reference Number: 040706JK June AAKF Albert Laguna National Friday April 7…………………7:00 – 9:00pm Guests Rate 10-11 Cheah Hills, CA Room Room Championship per Per ITKF Type Tax & VTA July AAKF San Diego, Saturday, April 8……………10:00 – -

INTERNATIONAL WTKO TRAINING CAMP and CHAMPIONSHIP 18Th to 21St July 2013 Thun, Switzerland Welcome to the International WTKO Training Camp and Championship

WTKO INTERNATIONAL WTKO TRAINING CAMP AND CHAMPIONSHIP 18th to 21st July 2013 Thun, Switzerland Welcome to the International WTKO Training Camp and Championship The WTKO Switzerland is proud to host this important event in the beautiful city of Thun. The organizing committee is well experienced, as it already showed at the JKA World Championship in 1998. After 15 years, the time is ready to bring traditional world class Karate back to our Coutry. It would be a pleasure, to welcome many people from around the world to this special event. We are looking forward to see you this summer in Switzerland WTKO Switzerland main instructors Born in England in 1963, Richard Amos sensei began karate at age 10. Occasionally teaching from as young as 15 he was invited onto the KUGB Junior Karate Team at 18. By the age of 23 he had competed in England and Europe gaining many Gold, Silver and Bronze medals in numerous championships. After a two-year sojourn in New York, he went to Japan to train at the headquarters of the Japan Karate Association and stayed 10 years. During that time he completed the 3-year instructor‘s program of the JKA (only the 2nd Westerner ever to do so in its 50-year history), placed second or third in the All-Japan Championships several times (no non-Japanese had ever reached the semi-finals before), taught many classes each week over a 6-year period in the headquarters of the JKA (another first) and opened his own school in the heart of Tokyo. -

Application of the Martial Arts' Pedagogy

WOJCIECH J. CYNARSKI THE traditionally UNDERSTOOD karate-DO AS AN educational SYSTEM: application OF THE martial arts’ pedagogy Introduction The scientific problem undertaken here is to clarify the application of the “karate pathway” in a specific educational system. A variety of theBudo Pedagogy is applied under the name of karate-do. Is karate really an educational system? The issue will be implemented from the perspective of the Humanistic Theory of Martial Arts and the anthropology of martial arts.1 It is the anthropology of the “warriors pathway,” as we can translate Budo sensu largo. Of course, Budo sensu stricto is an untranslatable concept, as a specific fragment of Japanese culture.2 Accordingly, we accept this conceptual language of the Humanistic Theory of Martial Arts and anthropology of martial arts. For instance, “Martial arts is a historic category of flawless methods of unarmed combat fights, and the use of weapons combined with a spiritual element (personal development, also in the transcendent sphere).”3 The ways of martial arts include certain forms of physical (psychophysical) culture, which, based on the tradition of warrior cultures, lead, through the training of fighting techniques, to a psychophysical improvement and self-realization. At the same time, they are the processes of education and positive ascetics. The positive asceticism combines corporal exercise with conscious self- discipline and is oriented towards moral and spiritual progress. 1 W.J. Cynarski, Teoria i praktyka dalekowschodnich sztuk walki w perspektywie europejskiej, Rzeszów 2004; W.J. Cynarski, Antropologia sztuk walki. Studia i szkice z socjologii i filozofii sztuk walki, Rzeszów 2012; D. -

Kihon Kata (Taikyoku Shodan)

Zanshin Kai Karate Do – Kata Series – Volume 01. Zanshin Kai Karate Do and Kobudo presents: KIHON KATA (TAIKYOKU SHODAN) Information, history, hints, tips, secrets – all revealed… by Gary Simpson 雅利 真風尊 © 2020 Gary Simpson & Zanshin Kai Karate Do & Kobudo 1 Zanshin Kai Karate Do – Kata Series – Volume 01. IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER NOTICE This manual is intended for educational purposes only. None of the material within these pages should be regarded as a substitute for ‘hands-on’ training. Every student of karate has different goals and expectations. This combined with vast differences in personality, knowledge, discipline, training, experience, understanding and ability means that every person will reach a different outcome. The information depicted within is the experience of the author over the many years of his karate journey. The material presented is offered in good faith and in the spirit of karate-do. There is no intention whatsoever to decry or criticize any other person, club, style. You are who you are. I am who I am. The author and publisher will not accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions. This material has been extensively checked. However, no responsibility whatsoever is accepted by the author for any material contained herein that may be inadvertently incorrect. To the best of his knowledge it is correct. Again, there is no intention by the author to disrespect any individual, style or organization with any of the material shared in this booklet. This booklet is about sharing knowledge and technique ONLY. Zanshin Kai Karate Do & Kobudo Published by: PO Box 396 Leederville Western Australia 6903 v 7.8-240520 © 2017, 2020 Gary Simpson & ZKKD. -

Bruce Lee As Method Daryl Joji Maeda

Nomad of the Transpacific: Bruce Lee as Method Daryl Joji Maeda American Quarterly, Volume 69, Number 3, September 2017, pp. 741-761 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2017.0059 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/670066 Access provided by University Of Colorado @ Boulder (19 Nov 2017 16:06 GMT) Bruce Lee as Method | 741 Nomad of the Transpacific: Bruce Lee as Method Daryl Joji Maeda The life of the nomad is the intermezzo. —Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari Be formless, shapeless, like water. —Bruce Lee he transpacific nomad Bruce Lee was born in San Francisco, raised in Hong Kong until the age of eighteen, came of age in Seattle, had his Thopes of movie stardom extinguished in Hollywood, and returned to Hong Kong to rekindle his dreams. In 1971 he made his first martial arts film, Tang Shan Daxiong, in which he played a Chinese immigrant to Thai- land who discovers that his boss is a drug-smuggling kingpin. The following year, he starred in Jing Wu Men as a martial artist who defends Chinese pride against Japanese imperialists in the International Settlement of early twentieth- century Shanghai. Because of the overwhelming popularity of both films in Hong Kong and throughout Asia, National General Pictures selected them for distribution in the United States in 1973. Tang Shan Daxiong was supposed to be released as The Chinese Connection to associate it with The French Con- nection, a mainstream hit about heroin trafficking; the title ofJing Wu Men was translated as Fist of Fury. -

Istoria-“JKA”, Şi Şcolilor De Karate Shotokan Derivate Din

Istoria-“JKA”, şi şcolilor de Karate Shotokan derivate din JKA Era Pre-Razboi ,o mica istorie.In anul 1922 -Okinawan Karate prin persoana Maestrului Gichin Funakoshi demonstreaza “TO-DE”in Ochanomizu,pentru Ministerului Educatiei din Japonia.In anul 1929 -In urma discutiilor cu Gyodo Furukawa(preot sef la Templul Enkaku, Kamakura) Funakoshi vazand asemanarile dintre filozofia ZEN si KARATE,dezvolta “spiritual de Karate”si schimba “TO-DE” în “KARATE”. In anul 1930- Era Razboi ,Masatoshi Nakayama si Masatomo Takagi au pastrat vie practica de Karate,dezvoltand-o aceasta în mod oficial. Funakoshi Shotokan Hombu Dojo a fost distrus în urma unui raid aerian de o bomba.In anul 1949 - Era Dupa-Razboi. Se fondeaza si are recunoaste provizorie în mod oficial (The JAPAN KARATE ASSOCIATION),Asociatia Japoneza de Karate prin intermediul lui Yoshinosuke Saigo(membru al Casei de Consiliu,a Guvernului Japonez).In anul 1953 -prin intermediul lui Tsutomu Oshima ,Hidetaka Nishiyama ” are acum 10 Dan conduce I.T.K.F.” primeste invitatie sa predea la Strategic Air Command (USA) Comandamentul Strategic Aerian American astfel introducand Karate în SUA-America,care este acum o arta Internationala. In anul 1955 - Funakoshi Sensei are 86 de ani, Takagi poarta conversatie si face planuri cu un producator de film Yuzuru Kataoka,pentru mediatizarea prin film a stilului Shotokan,si a noului Hombu Dojo.La sfarsitul anului Yuzuru Kataoka, îl suna pe Takagi ca sa afle despre ultimele stiri legate despre noul dojo,aceasta este centrul de baza în dezvoltare a JKA.In anul 1956 -Instructorii pregatitori dezvolta prin Nakayama Sensei si Nishiyama Sensei directia pe care se vor crea legendele de maine ale JKA. -

Pine Waves Newsletter Vol 10 Iss 3

Pine Waves, Vol. 11, No. 3 August 2007 Page 1 #2 Devon Henery Meaghan Henery Nathan Brockett Loren Arthur #3 Grace Wicklund © Loren Arthur AAKF NorthWest Region REGIONAL JKA-US NorthWest, Inc. Nathan Broekett Vol. 11, No. 3, August 2007 TOURNAMENT Youth Division 2 Saturday, May 5, 2007 Mark Your Calendar!! (Shorter folks) Corvallis, OR August Kata Summer Sensei Coos Bay, Regional Tournament Results 10-12, Seminar Nishiyama OR #1 Alex Castanares 2007 Note: colors denote: #2 Isaac Hall Vancouver October Red = First Place (“#1”) #3 Sylvester Canseco Fall Sensei VA Gym, 5-7 Seminar Fusaro Vancouver Blue = Second Place (“#2”) *updated WA Green = Third Place (“#3”) Kumite #1 Alex Castanares 4th Traditional October Warsaw, World Youth Division 1 #2 Pedro Rivas 5-7, 2007 Poland Championship (“Taller folks”) #3 Isaac Hall JKA-USNW Sensei Team Kata TBA TBA Kata Winter Nishiyama #1 Alyssa Steele #1 Hillsboro Shotokan Seminar Austin Holst April #2 Willie DeChant 13-15 Spring Chris Corvallis, #3 Linda Ditkovich Jordan Farris 2008 Seminar Smaby OR Isaac Hall *updated Kumite #2 Willamette The Pine Waves Newsletter is produced using #1 Meaghan Henery Chris Adobe Acrobat 7.0. To get the most recent #2 Willie DeChant Casey FREE Adobe Reader, please click on the icon #3 Ben Wallack Zachary Kimoto below: #3 Eugene Team Kata Angelina Rivas #1 Linda Ditkovich Jesus Rivas Ben Wallack Pedro Rivas Hannah Johnston Pine Waves, Vol. 11, No. 3 August 2007 Page 2 Adult White/Green belt Men #1 Guido Fischer Did you hear that? . Kata #2 Adam Wisseman #1 Steve Johnston #3 Ritch Rice “The real blocking techniques of karate do #2 Yuriy Shusterman not end simply with the blocking of an attack; #3 Dave Wing Team Kata according to the way the block is used, it can be #1 Willamette a strong kime-waza (decisive technique). -

1 American Judo Spring 2009

Spring 2009 1 American Judo Black Belt Magazine Offer for USJA Members Winter 2008 - 2009 USJA Officers FEATURED ARTICLES Dr. AnnMaria Rousey Photographing the New York Open Judo Championship by Sasha Shapiro .............. 4 DeMars President What Is A Person’s Best Effort? Steve Scott ............................................................................... 6 Coast Guard Judo Trains Hard, Plays Hard by Mark Jones ..............................................7 George Weers Secretary Remembering A Fighter by Ronald Allan Charles .................................................................. 8 Short People by E.E. Carol ...........................................................................................................10 Lowell F. Slaven Treasurer A Passing of a Great Friend of the Beginning of Martial Arts in the USA, Hidetaka Nishiyama, 9th Dan 1928-2008 ...............................................................................19 Gary S. Goltz Basic Principles Of Midori Ryu Jujitsu by Hal Zeidman ......................................................23 Chief Operating Officer JUDO NEWS and VIEWS 2009 US Open ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Legal Counsel Glenn Nakawaki 2008 USJA Awards ........................................................................................................................11 New USJA Membership Form .....................................................................................................14 -

Pine Waves Newsletter Vol 11 Iss 2

Pine Waves, Vol. 11, No. 2 March 2007 Page 1 Event schedule: Training ................... 10:00 a.m. – 5:00p.m. -- Heian Nidan & Yondan covered in early Spring Seminar sessions -- Jion & Nijushiho covered after lunch break Saturday © Kyu Exam ...................... 5:30 p.m. till done AAKF NorthWest Region *** JKA-US NorthWest, Inc. April 14, Instructors, please have exam Vol. 11, No. 2, March 2007 paperwork done ahead of time 2007 Vancouver to avoid delay. April Spring Regional VA Gym, 2007 Seminar Instructors Vancouver Fees: WA Vancouver, WA -- NW Regional Instructors are Full day May Judging Regular TBA TBA going to present an intensive one day event featuring 2007 Seminar KATA & APPLICATION training for: Individual ................................................$30.00 Student or family member...................... $22.50 HEIAN NIDAN May 4, Regional TBA TBA HEIAN YONDAN 2007 Tournament Half day only JION Regular AKF NIJUSHIHO Individual...................................... ....... $20.00 June Traditional Student or family member. ....................$15.00 8-9, Karate TBA Dallas, TX All training will be at the VA Medical Center Gym 2007 National (same place as the Winter Seminar), Championship Questions? Contact: 1601 E. Fourth Plain Blvd. July Gil Hartl ITKF Summer AAKF San Diego, Vancouver, WA 98661. 14-20, wk.: 541-259-1211 Camp Office CA 2007 Note: Instructors and students please work prior to cell phone: 541-401-3006 this event to develop basic knowledge of each kata. email: [email protected] August Summer Sensei TBA Everyone try to get to the point of knowing Or: 10-12, 2007 Seminar Nishiyama the basic walk-through of the kata movements at a Kathleen Resburg minimum. -

ITKF Media Release on the Passing of Hidetaka Nishiyama

INTERNATIONAL TRADITIONAL KARATE FEDERATION INTERNATIONAL OFFICE 1930 WILSHIRE BLVD., SUITE 1007 ● LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90057 ● U.S.A. ------- PHONE: 213/483-8262 ● FAX: 213/483-4060 ● E-MAIL: [email protected] MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release, November 8, 2008 JAPAN’S LIVING LEGEND DIES AT 80 (Los Angeles, CA) The International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF) is in mourning today following the passing of their President and Chairman, Hidetaka Nishiyama at the age of 80. Mr. Nishiyama was a world renowned karate master well known for his steadfast dedication to the preservation and protection of the Martial Art of Traditional Karate. “Mr. Nishiyama passed away peacefully following his struggle with cancer”, a family spokesperson said. Mr. Nishiyama dedicated his life to the Budo principles on which his beloved Martial Art of Traditional Karate is based. As a Charter Member of the Japan Karate Association and founding President of the Japan Karate Association International of America and the International Traditional Karate Federation, his influence on the modern day practice of Traditional Karate is unparalleled. “He was truly one of a kind”, said Acting ITKF Chairman, Rick Jorgensen. “He has greatly influenced and impacted the lives of those who practice Traditional Karate.” “His vision was very broad. It included people of all ages and all styles of karate”, said Jorgensen. “Sensei Nishiyama strongly held the belief that the Martial Art of Traditional Karate was a path of self development. School children, adults and seniors can use the principles of Traditional Karate to achieve their highest potential through the human development of mind, body and spirit.