Application of the Martial Arts' Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kyokushinkaikan Kumite Rules

International Karate Organization Kyokushinkaikan World Sokyokushin KYOKUSHINKAIKAN KUMITE RULES DURATION OF A MATCH 1.1 Each Kumite shall last 3 minutes. 1.2 If no decision in favour of either opponent is made by the 4 judges and the referee, and then the referee will authorize an extension, such extension to be limited to 2 minutes duration. 1.3 If after the first extension there is still no decision a further two minutes, ENCHO is given. If after this second two minutes a draw is given the contestants must be weighed. 1.4 If one of the competitors is lighter then the other for a value described below, such will be declared a winner. There is no Tameshiwari test. They must fight one more extension of 2 minutes duration and a decision must be made. If one of the competitors is lighter then the other for a value 5 kg or more, such will be declared a winner. (For men and woman both Category) CRITERIA FOR DECISION Full point win (IPPON-GACHI): The following cases will be judged as IPPON-GACHI (full point victory). 2.1 With the exception of techniques which are fouls and not allowed by the contest rules, any technique that connects and instantaneously downs the opponent for longer than 3 seconds, scores a full point. 2.2 If the opponent has loss of his will to fight for more than three seconds. When a contestant informs the referee or judges that he is beaten as the result of techniques allowed within the contest rules, his opponent shall be awarded a full point and the match. -

'Christian' Martial Arts

MY LIFE IN “THE WAY” by Gaylene Goodroad 1 My Life in “The Way” RENOUNCING “THE WAY” OF THE EAST “At the time of my conversion, I had also dedicated over 13 years of my life to the martial arts. Through the literal sweat of my brow, I had achieved not one, but two coveted black belts, promoting that year to second degree—Sensei Nidan. I had studied under some internationally recognized karate masters, and had accumulated a room full of trophies while Steve was stationed on the island of Oahu. “I had unwittingly become a teacher of Far Eastern mysticism, which is the source of all karate—despite the American claim to the contrary. I studied well and had been a follower of karate-do: “the way of the empty hand”. I had also taught others the way of karate, including a group of marines stationed at Pearl Harbor. I had led them and others along the same stray path of “spiritual enlightenment,” a destiny devoid of Christ.” ~ Paper Hearts, Author’s Testimony, pg. 13 AUTHOR’S NOTE: In 1992, I renounced both of my black belts, after discovering the sobering truth about my chosen vocation in light of my Christian faith. For the years since, I have grieved over the fact that I was a teacher of “the Way” to many dear souls—including children. Although I can never undo that grievous error, my prayer is that some may heed what I have written here. What you are about to read is a sobering examination of the martial arts— based on years of hands-on experience and training in karate-do—and an earnest study of the Scriptures. -

Asian Traditions of Wellness

BACKGROUND PAPER Asian Traditions of Wellness Gerard Bodeker DISCLAIMER This background paper was prepared for the report Asian Development Outlook 2020 Update: Wellness in Worrying Times. It is made available here to communicate the results of the underlying research work with the least possible delay. The manuscript of this paper therefore has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formally-edited texts. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. The ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this document and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or use of the term “country” in this document, is not intended to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this document do not imply any judgment on the part of the ADB concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. ASIAN TRADITIONS OF WELLNESS Gerard Bodeker, PhD Contents I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. -

Health and Martial Arts in Interdisciplinary Approach

ISNN 2450-2650 Archives of Budo Conference Proceedings Health and Martial Arts in Interdisciplinary Approach 1st World Congress September 17-19, 2015 Czestochowa, Poland Archives of Budo Archives od Budo together with the Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa organized the 1st World Congress on Health and Martial Arts in Interdisciplinary Approach under the patronage of Lech Wałęsa, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate. proceedings.archbudo.com Archives of Budu Conference Proceedings, 2015 Warsaw, POLAND Editor: Roman M Kalina Managing Editor: Bartłomiej J Barczyński Publisher & Editorial Office: Archives of Budo Aleje Jerozolimskie 87 02-001 Warsaw POLAND Mobile: +48 609 708 909 E-Mail: [email protected] Copyright Notice 2015 Archives of Budo and the Authors This publication contributes to the Open Access movement by offering free access to its articles distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and is otherwise in compliance with the license. The copyright is shared by authors and Archives of Budo to control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited. ISSN 2450-2650 Health and Martial Arts in Interdisciplinary Approach 1st World Congress • September 17-19, 2015 • Czestochowa, Poland Scientific Committee Prof. Roman Maciej KALINA Head of Scientific Committee University of Physical Education and Sports, Gdańsk, Poland Prof. Sergey ASHKINAZI, Lesgaft University of Physical Education, St. Petersburg, Russia Prof. Józef BERGIER, Pope John Paul II State School of Higher Education in Biała Podlaska, Poland Prof. -

Acute Changes of Achilles Tendon Thickness Investigated by Ultrasonography After Shotokan and Kyokushin Karate Training

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Acute changes of Achilles tendon thickness investigated by ultrasonography after shotokan and kyokushin karate training Authors’ Contribution: Andrzej Zarzycki1ABD, Mateusz Stawarz1BCD, John Maillette2BD, Nicola Lovecchio3CD, A Study Design 3,4CD 1AB 1ACD B Data Collection Matteo Zago , Adam Kawczyński , Sebastian Klich C Statistical Analysis D Manuscript Preparation 1 Department of Paralympics Sports, University School of Physical Education, Wroclaw, Poland E Funds Collection 2 Health and Human Performance, University of Wisconsin – River Falls, River Falls, USA 3 Department of Biomedical Sciences for Health, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy 4 Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering (DEIB), Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy Received: 23 May 2018; Accepted: 18 June 2018; Published online: 09 July 2018 AoBID: 12183 Abstract Background and Study Aim: Ultrasonography proved to be a useful tool to investigate the morphology of the Achilles tendon. Studies ex- ist assessing the role of exercise on Achilles tendon morphology after vertical jump and treadmill running, and Achilles tendon dimensions noticeably decreased following heavy resistance exercise. However, little is known regarding the influence of different karate disciplines as shotokan and kyokushin on Achilles tendon thickness. Thus, this study aimed to establish whether the acute changes of Achilles tendon are a phenome- non characteristic of different styles of karate training. Material and methods: Twenty-four male partcipants (12 shotokan and 12 kyokushin karate athletes) underwent sonographic ex- amination with Honda HS – 2200 (Honda, Japan) ultrasound scanner. The Achilles tendon of both legs was measured twice before and then immediately following training. The sagittal thickness of the tendon was ob- served at a point exactly 10 millimetres proximal to the calcaneal insertion. -

Agonology As a Deeply Esoteric Science – an Introduction to Martial Arts Therapy on a Global Scale

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Manufacturing 3 ( 2015 ) 1195 – 1202 6th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFE 2015) and the Affiliated Conferences, AHFE 2015 Agonology as a deeply esoteric science – an introduction to martial arts therapy on a global scale Roman Maciej Kalina* *GDĔVN8QLYHUVLW\RI3K\VLFDO(GXFDWLRQDQG6SRUW.*RUVNLHJR*GDQVN-336, Poland Editor and Chief of Archives of Budo, Aleje Jerozolimskie 87, Warsaw 02-001, Poland Abstract The struggle is the relation, which is common for people all over the world. It can be encountered from daily quarrel of two people, through political disputes, commercial competition, soccer matches, antiterrorist actions to military conflicts between countries. Increase in the frequency of these struggles and their brutalisation reached the border, which further crossing means that the lynch will become an acceptable way to claim own arguments and the freedom of speech and gestures will be tied up with the awareness of such sanctions.Paradoxically, television channels educate the most aggressively using the word “sport”. Beating unconscious, lying into the cage, dripping blood the neo-gladiator do not fall within a definition of “sport”. There is no exaggeration in stating that the brutalization of fights is the epidemic on the global scale. Always, when threats appear which is a concern of large populations, let alone the entire earth’s population, the hope is in the science.The general theory of struggle (agonology) waVHVWDEOLVKHGE\.RWDUELĔVNL .RQLHF]Q\GHYHORSHG DF\EHUQHWLFWKHRU\RIVWUXJJOH5XGQLDĔVNL created the theory of a non-armed struggle (1989). I’m the author the theory of defensive struggle (1991) and combat sports theory (2000). -

Cv for Sensei Samson Muripo

CV FOR SENSEI SAMSON MURIPO CONTACT AND PERSONAL DETAILS CONTACT ADDRESS: 50 Tower Close, Helensvale, Borrowdale, Harare Zimbabwe CONTACT NUMBERS: +263 773 434 812 / +263 772 313 135 DATE OF BIRTH: 05/05/78 IDENTITY NO: 44-074026-Z-44 NATIONALITY: Zimbabwean GENDER: Male LANGUAGES: English, Shona Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Background summary th • Renowned 4 Dan (YONDAN) Black Belt Kyokushin Karate World Champion with experience in international competitions and training. • First African World Kyokushin Karate Champion • Experienced trainer in mental and physical coordination • Skilled team and individual motivator • Team player • Dedicated to grassroots and international karate development • High regard for professionalism • Successful Trainer of Trainers Current positions • Zimbabwe So-Kyokushin – Chief Instructor • Council Member – International Karate Organization Kyokushinkaikan: World So- Kyokushin • Country Representative - International Karate Organization Kyokushinkaikan: World So-Kyokushin • Council Member - Zimbabwe Karate Union (Style Representative) • Council Member - Harare Metropolitan Province Karate Association (Style Representative) Local and International achievements • First ever African World Karate Champion Defeated Spanish, Kazakhstan, German, Australian and Japanese champions in the Men’s Middle Weight Category at the 1st World Cup Open Karate Tournament in Osaka, Japan, June 2009. 1 • Zimbabwe 2013 Sportsman of the Year • Champion in the Heavyweight Category of the 2013 Sokyokushin Cup Karate International Tournament in Shangai, China • Siver Medalist in the Superheavyweight Category of the 2013 Sokyokushin Cup International Karate Tournament in Shangai, China st • Best Technical Prize of the 1 World Cup Open Karate Tournament, Osaka, Japan, June 2009. • Silver Medalist at the Higashi Nippon International Kyokushin Karate-do Senshukentaikai Open Weight Tournament in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan, April 2010. -

HARDSTYLE 2 2004 Spring

Kettlebells, Bruce Lee and the Power of Icons When I first met Pavel at a stretching Explosive power. And almost mystical “I want to be like Bruce” workshop in Minneapolis, in early 1997, I strength gains (the notorious What the Hell? was immediately struck by his charismatic effect). For women, a toned, firm, strong Images can lodge in our brains and become ability to model and convey a stunning shape that enhances the best of the female an ideal that drives us forward. combination of strength and flexibility. Pavel body. For both genders, greater energy, cut through the BS in startling fashion, to higher self-esteem and greater sense of As a young man, in the seventies, Bruce Lee give you what really works. Just like Bruce… overall well being. had that impact on me. The classic image of Bruce—his ripped-to-shreds chest decorated Later that year Dragon Door published All delivered by one compact, portable with claw marks, posing in steely-sinewed, Pavel’s first book, Beyond Stretching, device, in just minutes a day… martial defiance—became my iconic followed by Beyond Crunches, the landmark inspiration for physical excellence. classic Power to the People! and finally, The Russian Kettlebell Challenge in 2001. And Physically, I wanted “to be like Bruce.” the fitness landscape in America changed And, of course Bruce influenced and inspired forever. Bruce Lee + Kettlebells millions like me to jump into martial 2 training and emulate his example. = Iconic Power What does Bruce Lee embody as an iconic And what better testimony to the iconic ideal? Raw, explosive power. -

Nonspecific Low Back Pain Among Kyokushin Karate Practitioners

medicina Article Nonspecific Low Back Pain among Kyokushin Karate Practitioners Wiesław Błach 1, Bartosz Klimek 2, Łukasz Rydzik 3,* , Pavel Ruzbarsky 4 , Wojciech Czarny 4, Ireneusz Ra´s 5 and Tadeusz Ambrozy˙ 3 1 Department of Sport, University School of Physical Education, 51-612 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] 2 Klimek Fizjoterapia, 31-541 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] 3 Institute of Sports Sciences, University of Physical Education in Krakow, 31-541 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department of Sports Kinanthropology, Faculty of Sports, Universtiy of Presov, 080-01 Prešov, Slovakia; [email protected] (P.R.); [email protected] (W.C.) 5 Doctoral School, University of Physical Education in Kraków, 31-571 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-730-696-377 Abstract: Background and objective: Spinal pain is a common and growing problem, not only in the general population but also among athletes. Lifestyle, occupation, and incorrectly exerted effort have a significant impact on low back pain. To assess the prevalence of low back pain among those practicing Kyokushin karate, we take into account age, body weight, sex, length of karate experience, level of skill, and occupation. Materials and Methods: The study involved 100 people practicing Kyokushin karate, aged 18 to 44. A questionnaire developed for this study and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) were used. Results: The research showed the prevalence of low back pain among karate practitioners (55%), depending on age (R = −0.24; p = 0.015), body weight (χ2 = 16.7; p = 0.002), occupation (χ2 = 18.4; p = 0.0004), and overall length of karate experience (R = −0.28; p = 0.04). -

Pine Waves Newsletter Vol 10 Iss 1

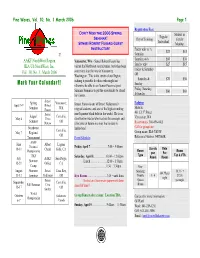

Pine Waves, Vol. 10, No. 1 March 2006 Page 1 Registration Fees: Don’t Miss the 2006 Spring Student or Regular Seminar! Day of Training Family Individual Sensei Robert Fusaro Guest Member Instructor! Friday only or ½ $25 $15 Saturday © Saturday only $50 $30 AAKF NorthWest Region Vancouver, WA – Sensei Robert Fusaro has JKA-US NorthWest, Inc. visited the Northwest several times, but it has been Sunday only $25 $15 Friday & Saturday Vol. 10, No. 1, March 2006 some time since he was in Vancouver, OR Washington. This is the center of our Region, making it possible for those who might not Saturday & $70 $50 Mark Your Calendar!! otherwise be able to see Sensei Fusaro at past Sunday Friday, Saturday, Summer Seminars to get the opportunity to attend $80 $60 & Sunday his classes. Spring Sensei Vancouver, Lodging April 7-9 Robert Sensei Fusaro is one of Sensei Nishiyama’s Seminar WA Shilo In Fusaro original students, and one of the highest ranking th non-Japanese black belts in the world. He is an 401 E 13 Street Judges’ Sensei Corvallis, May 6 Vince excellent instructor who teaches the concepts and Vancouver, WA Seminar OR Nistico principles of karate in a way that is easy to Reservations: 360-696-0411 Northwest understand. Call for group rate: Corvallis, May 7 Regional Group name: JKA-USNW OR Tournament Event Schedule Reference Number: 040706JK June AAKF Albert Laguna National Friday April 7…………………7:00 – 9:00pm Guests Rate 10-11 Cheah Hills, CA Room Room Championship per Per ITKF Type Tax & VTA July AAKF San Diego, Saturday, April 8……………10:00 – -

Long Way to the Czestochowa Declarations 2015: HMA Against MMA

Available online at proceedings.archbudo.com Archives of Budo Conference Proceedings 2015 HMA Congress 1st World Congress on Health and Martial Arts in Interdisciplinary Approach, HMA 2015 Long way to the Czestochowa Declarations 2015: HMA against MMA Roman Maciej Kalina1,2 Bartłomiej Jan Barczyński2,3 1 Gdansk University of Physical Education and Sport, Department of Combat Sports, Poland 2 Archives of Budo, Warsaw, Poland 3 4 MEDICINE REK LLP, Warsaw, Poland Abstract The main questions raised in our paper regarding the following issue which is very embarrassing for global society: why there are so many peo- ple who tolerate numerous pathologies related to people fighting, including to neo-gladiators? why neo-gladiators’ fights are considered equiva- lent with sport by media, in particular electronic ones, even though they clearly contradict the idea of “sport”? which side does the spectators of neo-gladiators’ fights identify themselves with – a winner or defeated, or does it even matter as bloody show is the most important thing? The aim of this review paper (partially falling into the category of research highlights) does not include full answers for the questions raised. On the contrary. We discuss a few premises, assumptions and hypothesis as well as several open questions. We believe that the issue is so important that, on one hand, it should be called into question in a broad perspective by scholars and various social entities and on the other hand it requires the necessary intensification of research and implementation into educational practice. This brief overview of the papers published in the last 10 years mainly in Archives of Budo, the only one in the global space science, which is dedicated to the science of martial arts, highlight health and utilitarian potential of martial arts, combat sports and arts of self-defence. -

INTERNATIONAL WTKO TRAINING CAMP and CHAMPIONSHIP 18Th to 21St July 2013 Thun, Switzerland Welcome to the International WTKO Training Camp and Championship

WTKO INTERNATIONAL WTKO TRAINING CAMP AND CHAMPIONSHIP 18th to 21st July 2013 Thun, Switzerland Welcome to the International WTKO Training Camp and Championship The WTKO Switzerland is proud to host this important event in the beautiful city of Thun. The organizing committee is well experienced, as it already showed at the JKA World Championship in 1998. After 15 years, the time is ready to bring traditional world class Karate back to our Coutry. It would be a pleasure, to welcome many people from around the world to this special event. We are looking forward to see you this summer in Switzerland WTKO Switzerland main instructors Born in England in 1963, Richard Amos sensei began karate at age 10. Occasionally teaching from as young as 15 he was invited onto the KUGB Junior Karate Team at 18. By the age of 23 he had competed in England and Europe gaining many Gold, Silver and Bronze medals in numerous championships. After a two-year sojourn in New York, he went to Japan to train at the headquarters of the Japan Karate Association and stayed 10 years. During that time he completed the 3-year instructor‘s program of the JKA (only the 2nd Westerner ever to do so in its 50-year history), placed second or third in the All-Japan Championships several times (no non-Japanese had ever reached the semi-finals before), taught many classes each week over a 6-year period in the headquarters of the JKA (another first) and opened his own school in the heart of Tokyo.