The Uses of Enchantment in John Keats and Led Zeppelin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dazed N Confused Song List

Dazed n Confused Song List Ozzy Osbourne - Crazy Train - Solo’s, Paranoid 163 Whitesnake - Still of the Night -100 - Solo’s Aerosmith - Walk this Way 109 - Sweet Emotion 99 Uriah Heep - Easy Living 161 Robin Trower - Day of the Eagle 132, No time 127 Joe Walsh - Rocky Mountain Way 83 Molly Hatchet - Dream 106, Flirting w/ Disaster 120 April Wine - Roller 141, Sign of the gypsy queen 138 Rush - Tom Sawyer 175, Limelight 138 Bob Seeger - Strut 116 Ratt - Round and Round solo’s 127, Van Halen - Panama 141, Beautiful Girls 205, Jump 129, Poundcake 105 Thin Lizzy - Jailbreak 145 Rick Derringer - Rock n Roll Hoochie Koo 200 Billy Idol - Rebel Yell 166 Montrose - Space Station #5 168 Led Zeppelin - Immigrant Song 113, (Whole Lotta Love, Bring it on Home, How Many More Times) Foghat - I Just Wanna Make Love to You 127, Slowride 114, Fool for the city 140 Ted Nugent - Stranglehold, Dog Eat Dog 136, Cat Scratch Fever 127 Neil Young - Rockin in the Free World 132 Heart - Barracuda 137 James Gang - Funk 49 91, Walk Away 102 Poison - Nothin But a Good Time 129, Talk Dirty to Me 158 Motley Crue - Mr. Brownstone106, Smokin in the boys room 135, Looks that kill 136, Iron Maiden - Run to the Hills 173 Skid Row - Youth Gone Wild 117 ZZ Top - Tush, Sharped dressed man 125 Scorpions - Rock You Like a Hurricane 126 Grand Funk Railroad - American Band 129 Doucette - Mamma Let Him Play 136 Sammy Hagar - Heavy Metal, There’s only one way to rock 153, I don’t need love 106 Golden Earring - Radar Love -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

A Purim Reader

Consider the Grogger: A Purim Reader 18forty.org/articles/consider-the-grogger-a-purim-reader Consider: Why do we use a grogger? In a world in which it sometimes feels like everything makes just a bit too much noise, why do we use these most annoying of noisemakers? In David Zvi Kalman’s award winning piece, “The Strange and Violent History of the Ordinary Grogger,” Kalman traces the history of this loud yet under-considered instrument of merry noise-making. As you might (not) expect, the grogger has a long history in a less than traditionally Puriminian context: celebrations of the burning of Judas. Judas, betrayer of a famous close friend of his (and namesake to a recent movie), has often been a stand-in for antisemitic anger over history. In Kalman’s words: The Burning of Judas was never officially sanctioned by the Roman Catholic or Orthodox Church, but it was common practice in Europe until the 20th century and is still frequently performed in Latin America. While details vary by location, the basics are the same: An effigy of Judas is first hanged, then burned. It was in the context of this ceremony that the crotalus first morphed from church object to child object, as children responded to the flaming effigy by twirling their rattles in celebration. It still happens today; you can find images of a Czech anti- Judas rattle procession. Early on, the rattle’s distinctive sound became part of the ritual. As elsewhere, people understood it to be a violent sound; some compared it to the sound of nails being driven into Jesus’ hands. -

Vinyl Theory

Vinyl Theory Jeffrey R. Di Leo Copyright © 2020 by Jefrey R. Di Leo Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to publish rich media digital books simultaneously available in print, to be a peer-reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. The complete manuscript of this work was subjected to a partly closed (“single blind”) review process. For more information, please see our Peer Review Commitments and Guidelines at https://www.leverpress.org/peerreview DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11676127 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-015-4 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-016-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954611 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Without music, life would be an error. —Friedrich Nietzsche The preservation of music in records reminds one of canned food. —Theodor W. Adorno Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 1. Late Capitalism on Vinyl 11 2. The Curve of the Needle 37 3. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Led Zeppelin Iii & Iv

Guitar Lead LED ZEPPELIN III & IV Drums Bass (including solos) Guitar Rhythm Guitar 3 Keys Vocals Backup Vocals Percussion/Extra 1 IMMIGRANT SONG (SD) Aidan RJ Dahlia Ben & Isabelle Kelly Acoustic (main part with high Low acoustic 2 FRIENDS (ENC) (CGCGCE) Mack notes) - Giulietta chords - Turner Strings - Ian Eryn Congas - James Synth (riffy chords) - (strummy chords) - (transitions from 3 CELEBRATION DAY (ENC) James Mack Jimmy Turner Slide - Aspen Friends) - ??? Giulietta Eryn SINCE I'VE BEEN LOVING YOU (Both Rhythm guitar 4 schools) Jaden RJ under solo - ??? Organ - ??? Kelly 5 OUT ON THE TILES (SD) Ethan Ben Dahlia Ryan Kelly Acoustic (starts at Electric solo beginning) - Aspen, (starts at 3:30) - Acoustic (starts at 6 GALLOWS POLE (ENC) Jimmy Mack James 1:05) - Turner Mandolin - Ian Eryn Banjo - Giulietta Electric guitar (including solo Acoustic and wahwah Acoustic main - Rhythm - 7 TANGERINE (SD) (First chord is Am) Ethan Aidan parts) - Isabelle Ben Dahlia Kelly Ryan g Electric slide - Acoustic - Aspen, Mandolin - 8 THAT'S THE WAY (ENC) (DGDGBD) RJ Turner Acoustic #2 - Ian Jimmy Giulietta Eryn Tambo - James Claps - Jaden, Acoustic - Shaker -Ethan, 9 BRON-YR-AUR STOMP (SD) (CFCFAC) Aidan Jaden Dahlia Acoustic - Ben Ryan Kelly Castanets - Kelly HATS OF TO YOU (ROY) HARPER Acoustic slide - 10 (CGCEGC) ??? 11 BLACK DOG (ENC) Jimmy Mack Giulietta James Aspen Eryn Giulietta Piano (starts after solo) - 12 ROCK AND ROLL (SD) Ethan Aidan Dahlia Isabelle Rebecca Ryan Tambo - Aidan Acoustic - Mandolin - The Sandy Jimmy, Acoustic Giulietta, Mandolin -

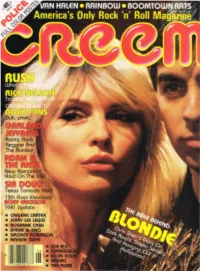

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Led Zeppelin Download Album the Top 100 Best Selling Albums of All Time

led zeppelin download album The Top 100 Best Selling Albums of All Time. What’s the best selling album of all time? The answer might surprise you, based on certified sales by the RIAA. In 2018, The Eagles’ Their Greatest Hits (1971—1975) surpassed Michael Jackson’s Thriller as the best selling album of all time in the United States. Since that point, the lead has only widened. The Eagles album has now sold more than 38 million copies according to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), thanks in part to continued touring across the United States and sustained interest on streaming platforms like Spotify. Their Greatest Hits (1971—1975) debuted in 1976 and included many of the group’s classics like “Take It Easy” and “Witchy Woman.” These sales figures compiled by the RIAA include disc and streaming sales. Thriller briefly overtook the Eagles compilation as the best selling album of all time in 2009 after Jackson’s death caused a surge in sales. But recent accusations against Jackson involving sexual assault may have softened sales for the pop superstar. Led Zeppelin IV (Remastered) Years after Led Zeppelin IV became one of the most famous albums in the history of rock music, Robert Plant was driving toward the Oregon Coast when the radio caught his ear. The music was fantastic: old, spectral doo-wop—nothing he’d ever heard before. When the DJ came back on, he started plugging the station’s seasonal fundraiser. Support local radio, he said—we promise we’ll never play “Stairway to Heaven.” Plant pulled over and called in with a sizable donation. -

A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell's Kitchen Liner Notes

Led Blimpie: A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell’s Kitchen Liner Notes Originally begun as a 3 song demo, this project evolved into a full-on research project to discover the recording styles used to capture Zeppelin's original tracks. Sifting through over 3 decades of interviews, finding the gems where Page revealed his approach, the band enrolled in “Zeppelin University” and received their doctorate in “Jimmy Page's Recording Techniques”. The result is their thesis, an album entitled: A Tribute to Led Zeppelin from Hell's Kitchen. The physical CD and digipack are adorned with original Led Blimpie artwork that parodies the iconic Zeppelin imagery. "This was one of the most challenging projects I've ever had as a producer/engineer...think of it; to create an accurate reproduction of Jimmy Page's late 60's/early 70's analog productions using modern recording gear in my small project studio. Hats off to the boys in the band and to everyone involved.. Enjoy!" -Freddie Katz Co-Producer/Engineer Following is a track-by-track telling of how it all came together by Co-Producer and Led Blimpie guitarist, Thor Fields. Black Dog -originally from Led Zeppelin IV The guitar tone on this particular track has a very distinct sound. The left guitar was played live with the band through a Marshall JCM 800 half stack with 4X12's, while the right and middle (overdubbed) guitars went straight into the mic channel of the mixing board and then into two compressors in series. For the Leslie sounds on the solo, we used the Neo Instruments “Ventilator" in stereo (outputting to two amps). -

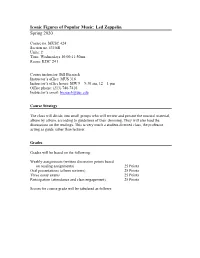

MUSC 424 Led Zeppelin Spring 20

Iconic Figures of Popular Music: Led Zeppelin Spring 2020 Course no. MUSC 424 Section no. 47256R Units: 2 Time: Wednesdays 10:00-11:50am Room: KDC 241 Course instructor: Bill Biersach Instructor’s office: MUS 316 Instructor’s office hours: MW 9 – 9:30 am, 12 – 1 pm Office phone: (213) 740-7416 Instructor’s email: [email protected] Course Strategy The class will divide into small groups who will review and present the musical material, album by album, according to guidelines of their choosing. They will also lead the discussions on the readings. This is very much a student-directed class, the professor acting as guide rather than lecturer. Grades Grades will be based on the following: Weekly assignments (written discussion points based on reading assignments) 25 Points Oral presentations (album reviews) 25 Points Three essay exams 25 Points Participation (attendance and class engagement) 25 Points Scores for course grade will be tabulated as follows: Texts Required (available in paperback or Kindle format): Cole, Richard Stairway to Heaven: Led Zeppelin Uncensored Dey St. (An Imprint of William Morrow Publishers), It Books; Reprint Edition, 2002 ISBN-13: 978-0060938376 Kindle: Harper Collins e-books; Reprint edition, 2009 ASIN: B000TG1X70 Davis, Stephen Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga Dey St. (An Imprint of William Morrow Publishers), It Books; Reprint Edition, 2008 ISBN: 978-0-06-147308-1 pk. Led Zeppelin Spring 2020 Schedule of Discussion Topics and Reading Assignments WEEK ALBUM DATE Stephen Davis Richard Cole Hammer of Stairway to Heaven: the Gods Led Zep Uncensored 1. Preliminaries Jan. -

Issue 6 £1.50

Issue 6 £1.50 "THE ALTERNATIVE TO CREEM" e h , r e m u s n o c e h t o t t c u d o r p s i h l l e s t ' n s e o d t n a h c r e m k n u j e h T “ sells the consumer to his product. He does not improve and improve not does He product. his to consumer the sells You're my kinda scum... kinda my You're most esteemed rag and the weirdo's who wrote it. it. wrote who weirdo's the and rag esteemed most obvs). This is my not-so-subtle nod to that once once to that nod is my not-so-subtle This obvs). writing goes, is Creem Magazine (pre-shittening, (pre-shittening, is Magazine goes, Creem writing Single Single Malt but one of the main things, as far unfluenced by all sorts of shit, from Sabbath to Sabbath from of shit, by sorts all unfluenced new new mascot, Cap'n Elmlee. Why? Well, I'm the the cover. I'm pleased to introduce you to our You You may also have noticed the cheeky chappie on n' greet. n' time you get invited to your local sex cult meet meet cult sex local to your invited get you time stick by us you won't look like such a noob next next a noob such like look won't you us by stick rama rama starting on page 4, meaning that if you kick kick off a new feature, a veritable sleaze-o- Bloodbath's Bloodbath's done-gone global! Oh yeah, and we Saturn from the California branch. -

The Song Remains the Same

Copyright Lighting&Sound America March 2008 CONCERTS www.lightingandsoundamerica.com the song remains the same A tribute to Ahmet Ertegun is the occasion for the historic reunion of Led Zeppelin n a year that saw some big events realized by team of top industry pro- who was involved in the initial design Iin the English concert world— fessionals. The process began during for the show; and Zeppelin’s produc- including Live Earth and the Concert the summer, when the event was not tion manager, Steve Iredale, who for Diana—few created as much fully confirmed. “Once we got the go- came onboard fairly early on.” excitement as the return of Led ahead,” says production manager Jim Zeppelin for a concert in memory of Baggott, “we spoke to some key Video Ahmet Ertegun, the late founder of people—such as lighting designer All involved envisioned a big, open Atlantic Records. Dave Hill; live image and video director stage with plenty of imagery. “The The event, a fundraiser for Dick Carruthers; Mark Norton from band was involved, right from the Ertegun’s education fund held at the Thinkfarm, who provided the show’s start, with how their part of the show O2 Arena on December 10, was projection imagery; Peter Bingham, was going to look,” says Baggott. Photos: Ed Robinson@one red eye March 2008 • Lighting&Sound America “We knew we wanted to steer away able to have a bit more practice.” and Jim Parsons as producer. from the traditional left /right screen “We arrived at the O2 at 8am on The end result was a combination arrangement and use one big screen the 9th December,” adds CT’s busi- of abstract images and soft-edged to back them.” ness development manager, Adrian video, creating a mood and pace It became apparent that a tradi- Offord.