Undressing and Redressing the Harlequin: an Australian Designer's Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

III. Discussion Questions A. Individual Stories Nathaniel Hawthorne

III. Discussion Questions a. Individual Stories Nathaniel Hawthorne, “Rappaccini’s Daughter” (1844) 1. As an early sf tale, this story makes important contributions to the sf megatext. What images, situations, plots, characters, settings, and themes do you recognize in Hawthorne’s story that recur in contemporary sf works in various media? 2. In Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, the worst sin is to violate, “in cold blood, the sanctity of the human heart.” In what ways do the male characters of “Rappaccini’s Daughter” commit this sin? 3. In what ways can Beatrice be seen as a pawn of the men, as a strong and intelligent woman, as an alien being? How do these different views interact with one another? 4. Many descriptions in the story lead us to question what is “Actual” and what is “Imaginary”? How do these descriptions function to work both symbolically and literally in the story? 5. What is the attitude toward science in the story? How can it be compared to the attitude toward science in other stories from the anthology? Jules Verne, excerpt from Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) 1. Who is narrator of this tale? In your opinion, why would Verne choose this particular character to be the narrator? Describe his relationship with the other members of this subterranean expedition. Many of Verne’s early novels feature a trio of protagonists who symbolize the “head,” the “heart,” and the “hand.” Why? How does this notion apply to the protagonists in Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth? 2. -

98Th ISPA Congress Melbourne Australia May 30 – June 4, 2016 Reimagining Contents

98th ISPA Congress MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA MAY 30 – JUNE 4, 2016 REIMAGINING CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE & COUNTRY 2 MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, 3 STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF PROGRAMMING, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 5 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 6 MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 7 LET THE COUNTDOWN BEGIN: A SHORT HISTORY OF ISPA 8 MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA 10 CONGRESS VENUES 11 TRANSPORT 12 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 13 ISPA UP LATE 14 WHERE TO EAT & DRINK 15 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 16 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 18 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SPEAKERS 22 CONGRESS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 28 CONGRESS PERFORMANCES 37 CONGRESS AWARD WINNERS 42 CONGRESS SESSION SPEAKERS & MODERATORS 44 THE ISPA FELLOWSHIP CHALLENGE 56 2016 FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMS 57 ISPA FELLOWSHIP RECIPIENTS 58 ISPA STAR MEMBERS 59 ISPA OUT ON THE TOWN SCHEDULE 60 SPONSOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 66 ISPA CREDITS 67 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE CREDITS 68 We are committed to ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to become immersed in ISPA Melbourne. To help us make the most of your experience, please ask us about Access during the Congress. Cover image and all REIMAGINING images from Chunky Move’s AORTA (2013) / Photo: Jeff Busby ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR & COUNTRY CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, Arts Centre Melbourne respectfully acknowledges STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA the traditional owners and custodians of the land on Whether you’ve come from near or far, I welcome all which the 98th International Society for the Performing delegates to the 2016 ISPA Congress, to Australia’s Arts (ISPA) Congress is held, the Wurundjeri and creative state and to the world’s most liveable city. -

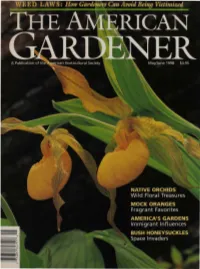

Willi Orchids

growers of distinctively better plants. Nunured and cared for by hand, each plant is well bred and well fed in our nutrient rich soil- a special blend that makes your garden a healthier, happier, more beautiful place. Look for the Monrovia label at your favorite garden center. For the location nearest you, call toll free l-888-Plant It! From our growing fields to your garden, We care for your plants. ~ MONROVIA~ HORTICULTURAL CRAFTSMEN SINCE 1926 Look for the Monrovia label, call toll free 1-888-Plant It! co n t e n t s Volume 77, Number 3 May/June 1998 DEPARTMENTS Commentary 4 Wild Orchids 28 by Paul Martin Brown Members' Forum 5 A penonal tour ofplaces in N01,th America where Gaura lindheimeri, Victorian illustrators. these native beauties can be seen in the wild. News from AHS 7 Washington, D . C. flower show, book awards. From Boon to Bane 37 by Charles E. Williams Focus 10 Brought over f01' their beautiful flowers and colorful America)s roadside plantings. berries, Eurasian bush honeysuckles have adapted all Offshoots 16 too well to their adopted American homeland. Memories ofgardens past. Mock Oranges 41 Gardeners Information Service 17 by Terry Schwartz Magnolias from seeds, woodies that like wet feet. Classic fragrance and the ongoing development of nell? Mail-Order Explorer 18 cultivars make these old favorites worthy of considera Roslyn)s rhodies and more. tion in today)s gardens. Urban Gardener 20 The Melting Plot: Part II 44 Trial and error in that Toddlin) Town. by Susan Davis Price The influences of African, Asian, and Italian immi Plants and Your Health 24 grants a1'e reflected in the plants and designs found in H eading off headaches with herbs. -

Harlequin RIP OEM Manual

0RIPMate for Windows operating systems Harlequin PLUS Server RIP v9.0 June 2011 AG12325 Rev. 13 Copyright and Trademarks Harlequin PLUS Server RIP June 2011 Part number: HK‚9.0‚ÄìOEM‚ÄìWIN Document issue: 106 Copyright ¬© 2011 Global Graphics Software Ltd. All rights reserved. Certificate of Computer Registration of Computer Software. Registration No. 2006SR05517 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Global Graphics Software Ltd. The information in this publication is provided for information only and is subject to change without notice. Global Graphics Software Ltd and its affiliates assume no responsibility or liability for any loss or damage that may arise from the use of any information in this publication. The software described in this book is furnished under license and may only be used or cop- ied in accordance with the terms of that license. Harlequin is a registered trademark of Global Graphics Software Ltd. The Global Graphics Software logo, the Harlequin at Heart Logo, Cortex, Harlequin RIP, Harlequin ColorPro, EasyTrap, FireWorks, FlatOut, Harlequin Color Management System (HCMS), Harlequin Color Production Solutions (HCPS), Harlequin Color Proofing (HCP), Harlequin Error Diffusion Screening Plugin 1-bit (HEDS1), Harlequin Error Diffusion Screening Plugin 2-bit (HEDS2), Harlequin Full Color System (HFCS), Harlequin ICC Profile Processor (HIPP), Harlequin Standard Color System (HSCS), Harlequin Chain Screening (HCS), Harlequin Display List Technology (HDLT), Harlequin Dispersed Screening (HDS), Harlequin Micro Screening (HMS), Harlequin Precision Screening (HPS), HQcrypt, Harlequin Screening Library (HSL), ProofReady, Scalable Open Architecture (SOAR), SetGold, SetGoldPro, TrapMaster, TrapWorks, TrapPro, TrapProLite, Harlequin RIP Eclipse Release and Harlequin RIP Genesis Release are all trademarks of Global Graphics Software Ltd. -

The Children of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre. Tony Earnest Medlin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Medlin, Tony Earnest, "The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7281. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7281 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Desajustamento: a Hermenêutica Do Fracasso E a Poética Do

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY E-ISSN 2237-2660 Misfitness: the hermeneutics of failure and the poetics of the clown – Heidegger and clowns Marcelo BeréI IUniversity of London – London, United Kingdom ABSTRACT – Misfitness: the hermeneutics of failure and the poetics of the clown – Heidegger and clowns – The article presents some Heideggerian ideas applied to the art of clowning. Four principles of practice of the clown’s art are analysed in the light of misfitness – a concept based on the clown’s ability not to fit into theatrical, cinematic and social conventions, thus creating a language of his own. In an ontological approach, this article seeks to examine what it means to be a clown-in-the-world. Following a Heideggerian principle, the clown is analysed here taking into account his artistic praxis; a clown is what a clown does: this is the basic principle of clown poetics. The conclusion proposes a look at the clown’s way of thinking – which is here called misfit logic – and shows the hermeneutics of failure, where the logic of success becomes questionable. Keywords: Heidegger. Clown. Phenomenology. Philosophy. Theatre. RÉSUMÉ – Misfitness (Inadaptation): l’herméneutique de l’échec et la poétique du clown – Heidegger et les clowns – L’article présente quelques idées heideggeriennes appliquées à l’art du clown. Quatre principes de pratique de l’art du clown sont analysés à la lumière de l’inadéquation – un concept basé sur la capacité du clown à ne pas s’inscrire dans les conventions théâtrales, cinématiques et sociales, créant ainsi son propre langage. Dans une approche ontologique, cet article cherche à examiner ce que signifie être un clown dans le monde. -

THEATRE DVD & Streaming & Performance

info / buy THEATRE DVD & Streaming & performance artfilmsdigital OVER 450 TITLES - Contemporary performance, acting and directing, Image: The Sydney Front devising, physical theatre workshops and documentaries, theatre makers and 20th century visionaries in theatre, puppets and a unique collection on asian theatre. ACTING / DIRECTING | ACTING / DEVISING | CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE WORKSHOPS | PHYSICAL / VISUAL THEATRE | VOICE & BODY | THEATRE MAKERS PUPPETRY | PRODUCTIONS | K-12 | ASIAN THEATRE COLLECTION STAGECRAFT / BACKSTAGE ACTING / DIRECTING Director and Actor: Passions, How To Use The Beyond Stanislavski - Shifting and Sliding Collaborative Directing in Process and Intimacy Stanislavski System Oyston directs Chekhov Contemporary Theatre 83’ | ALP-Direct |DVD & Streaming 68’ | PO-Stan | DVD & Streaming 110’ | PO-Chekhov |DVD & Streaming 54 mins | JK-Slid | DVD & Streaming 50’ | RMU-Working | DVD & Streaming An in depth exploration of the Peter Oyston reveals how he com- Using an abridged version of The works examine and challenge Working Forensically: complex and intimate relationship bines Stanislavski’s techniques in a Chekhov’s THE CHERRY ORCHARD, the social, temporal and gender between Actor and Director when systematic approach to provide a Oyston reveals how directors and constructs within which women A discussion between Richard working on a play-text. The core of full rehearsal process or a drama actors can apply the techniques of in particular live. They offer a Murphet (Director/Writer) and the process presented in the film course in microcosm. An invaluable Stanislavski and develop them to positive vision of the feminine Leisa Shelton (Director/Performer) involves working with physical and resource for anyone interested in suit contemporary theatre. psyche as creative, productive and about their years of collaboration (subsequent) emotional intensity the making of authentic theatre. -

Download Lot Listing

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Wednesday, May 10, 2017 NEW YORK IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART EUROPEAN & AMERICAN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION Wednesday, May 10, 2017 at 11am EXHIBITION Saturday, May 6, 10am – 5pm Sunday, May 7, Noon – 5pm Monday, May 8, 10am – 6pm Tuesday, May 9, 9am – Noon LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $40 INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART 1-118 Elsie Adler European 1-66 The Eileen & Herbert C. Bernard Collection American 67-118 Charles Austin Buck Roberta K. Cohn & Richard A. Cohn, Ltd. POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 119-235 A Connecticut Collector Post-War 119-199 Claudia Cosla, New York Contemporary 200-235 Ronnie Cutrone EUROPEAN ART Mildred and Jack Feinblatt Glossary I Dr. Paul Hershenson Conditions of Sale II Myrtle Barnes Jones Terms of Guarantee IV Mary Kettaneh Information on Sales & Use Tax V The Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois Buying at Doyle VI Carol Mercer Selling at Doyle VIII A New Jersey Estate Auction Schedule IX A New York and Connecticut Estate Company Directory X A New York Estate Absentee Bid Form XII Miriam and Howard Rand, Beverly Hills, California Dorothy Wassyng INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Private Beverly Hills Collector The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz sold for the benefit of the Bard Graduate Center A New England Collection A New York Collector The Jessye Norman ‘White Gates’ Collection A Pennsylvania Collection A Private -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

PLAYNOTES Season: 43 Issue: 04

PLAYNOTES SEASON: 43 ISSUE: 04 PORTLANDSTAGE BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Theater of Maine INTERVIEWS & COMMENTARY www.portlandstage.org AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY Discussion Series The Artistic Perspective, hosted by Artistic Director Anita Stewart, is an opportunity for audience members to delve deeper into the themes of the show through conversation with special guests. A different scholar, visiting artist, playwright, or other expert will join the discussion each time. The Artistic Perspective discussions are held after the first Sunday matinee performance. Page to Stage discussions are presented in partnership with the Portland Public Library. These discussions, led by Portland Stage artistic staff, actors, directors, and designers answer questions, share stories and explore the challenges of bringing a particular play to the stage. Page to Stage occurs at noon on the Tuesday after a show opens at the Portland Public Library’s Main Branch. Feel free to bring your lunch! Curtain Call discussions offer a rare opportunity for audience members to talk about the production with the performers. Through this forum, the audience and cast explore topics that range from the process of rehearsing and producing the text to character development to issues raised by the work Curtain Call discussions are held after the second Sunday matinee performance. All discussions are free and open to the public. Show attendance is not required. To subscribe to a discussion series performance, please call the Box Office at 207.774.0465. Portland Stage Company Educational Programs are generously supported through the annual donations of hundreds of individuals and businesses, as well as special funding from: The Davis Family Foundation Funded in part by a grant from our Educational Partner, the Maine Arts Commission, an independent state agency supported by the National Endowment for the Arts. -

Surviving Set Theory: a Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory

Surviving Set Theory: A Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Angela N. Ripley, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: David Clampitt, Advisor Anna Gawboy Johanna Devaney Copyright by Angela N. Ripley 2015 Abstract Undergraduate music students often experience a high learning curve when they first encounter pitch-class set theory, an analytical system very different from those they have studied previously. Students sometimes find the abstractions of integer notation and the mathematical orientation of set theory foreign or even frightening (Kleppinger 2010), and the dissonance of the atonal repertoire studied often engenders their resistance (Root 2010). Pedagogical games can help mitigate student resistance and trepidation. Table games like Bingo (Gillespie 2000) and Poker (Gingerich 1991) have been adapted to suit college-level classes in music theory. Familiar television shows provide another source of pedagogical games; for example, Berry (2008; 2015) adapts the show Survivor to frame a unit on theory fundamentals. However, none of these pedagogical games engage pitch- class set theory during a multi-week unit of study. In my dissertation, I adapt the show Survivor to frame a four-week unit on pitch- class set theory (introducing topics ranging from pitch-class sets to twelve-tone rows) during a sophomore-level theory course. As on the show, students of different achievement levels work together in small groups, or “tribes,” to complete worksheets called “challenges”; however, in an important modification to the structure of the show, no students are voted out of their tribes.