Why Black Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Permanent Call Number Douglass Collection "I Will Wear No Chain!" : a Social History of African-American Males / Christopher B

Location Name Title (Complete) Permanent Call Number Douglass Collection "I will wear no chain!" : a social history of African-American males / Christopher B. Booker. E185.86 .B635 2000 Douglass Collection "No man can hinder me" : black troops in the Union armies during the American Civil War : an exhibition at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, December 2003--E540.N3 H86 Douglass Collection "We specialize in the wholly impossible" : a reader in Black women's history / edited by Darlene Clark Hine, Wilma King, Linda Reed. E185.86 .W435 1995 Douglass Collection "When I can read my title clear" : literacy, slavery, and religion in the antebellum South / Janet Duitsman Cornelius. E443 .C7 1991 Douglass Collection 100 years of Negro freedom. E185.6 .B74 1962 Douglass Collection A Black woman's Civil War memoirs : reminiscences of my life in camp with the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops, late 1st South Carolina Volunteers / Susie King Taylor ; edited by PE492.94 33rd .T3 1988 Douglass Collection A Documentary history of slavery in North America / edited with commentary by Willie Lee Rose. E441 .D64 Douglass Collection A Southern woman's story / Phoebe Yates Pember ; with a new introduction by George C. Rable. E625 .P39 2002 Douglass Collection A death in Texas : a story of race, murder, and a small town's struggle for redemption / Dina Temple-Raston. HV6534.J36 T45 2002 Douglass Collection A gathering of old men / Ernest J. Gaines. PS3557.A355 G3 1997 Douglass Collection A gentleman of color : the life of James Forten / Julie Winch. E185.97.F717 W56 2002 Douglass Collection A heritage of woe : the Civil War diary of Grace Brown Elmore, 1861-1868 / edited by Marli F. -

2010 Harlem Book Fair Program & Schedule

2010 HARLEM BOOK FAIR PROGRAM & SCHEDULE Tribute to Book-TV Presented by Max Rodriguez, Founder – Harlem Book Fair Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium 11:00a - 11:15a Tribute to Howard Dodson, Chief of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Presented by Herb Boyd; Max Rodriguez; Kassahun Checole Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium 11:15a - 11:30a SCHOMBURG C-SPAN PANEL DISCUSSIONS God Is Not A Christian: Can We All Get Along in A World of Holy Wars and Religious Chauvinism? Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium (Televised Live on C-Span’s Book-TV) 11:40a - 12:55p Who is the one true God? Who are the chosen people? Questions like these have driven a thousand human struggles through war, terrorism and oppression. Humanity has responded by branching off into multiple religions--each one pitted against the other. But it doesn't have to be that way, according to Bishop Carlton Pearson and many others. This New Thought spiritual leader will discuss these and many other burning questions with author and theologian, Obery Hendricks and others. MODERATOR: Malaika Adero, Up South: Stories, Studies, and Letters of This Century's African American Migrations, The New Press PANELISTS: Obrey Hendricks, The Politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the True Revolutionary Nature of Jesus' Teachings and How They Have Been Corrupted (Doubleday); Bishop Carlton Pearson, God is Not a Christian, Nor a Jew, Muslim, Hindu...God Dwells with Us, in Us, Around Us, as Us (Simon&Schuster), Sarah Sayeed,, and others. Book signing immediately following discussion in Schomburg lobby. Is Racial Justice Passe? Barack Obama, American Society, and Human Rights in the 21st Century Schomburg/Hughes Auditorium (Televised Live on C-Span’s Book-TV) 1:05p - 2:20p Barack Obama's election as the 44th President of the United States upends conventional notions of citizenship, racial justice, and equality that contoured the modern civil rights movement. -

A Bibliography of Contemporary North American Indians : Selected and Partially Annotated with Study Guides / William H

A Catalog of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center Library Materials On‐Loan to the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County Cataloged by the Staff of the Cataloging Services Department Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County Edited by Roger M. Miller Cataloging Services Department Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County September 2008 The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County 800 Vine Street Cincinnati, Ohio 45202‐2071 513‐369‐6900 www.cincinnatilibrary.org The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, located on the banks of the Ohio River in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio, opened its doors on August 23, 2004. The Freedom Center facility initially included the John Rankin Library, but funding issues eventually lead to the elimination of the librarian position and closing the library to the public. In the fall of 2007, the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County and The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center entered into an agreement for their John Rankin Library to be housed at the Main Library in downtown Cincinnati as a long‐term loan. The initial loan period is 10 years. The items from the Freedom Center have been added to the Library’s catalog and have been incorporated into the Main Library’s Genealogy & Local History collection. These materials are available for the public to check out, if a circulating item, or to use at the Main Library, if a reference work. The unique nature of the Freedom Center’s collection enhances the Main Library’s reference and circulating collections while making the materials acquired by the Freedom Center again available to the public. -

Page 1 of 143 Ventura County Library Diversity, Inclusion, & Anti

Ventura County Library Diversity, Inclusion, & Anti-RacismSort All Featured White Fragility By: DiAngelo, Robin; Dyson, Michael Eric ISBN: 9780807047422 Published By: Beacon Press 2018 EPUB3 View book URL https://ebook.yourcloudlibrary.com/library/venturacountylibrary-document_id-qv1u1r9 The New York Times best-selling book exploring the counterproductive reactions white people have when their assumptions about race are challenged, and how these reactions maintain racial inequality. In this “vital, necessary, and beautiful book” (Michael Eric Dyson), antiracist educator Robin DiAngelo deftly illuminates the phenomenon of white fragility and “allows us to understand racism as a practice not restricted to ‘bad people’ (Claudia Rankine). Referring to the defensive moves that white people make when challenged racially, white fragility is characterized by emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and by behaviors including argumentation and silence. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium and prevent any meaningful cross-racial dialogue. In this in-depth exploration, DiAngelo examines how white fragility develops, how it protects racial inequality, and what we can do to engage more constructively. Page 1 of 143 Let Them See You By: Braswell, Porter ISBN: 9780399581410 Published By: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale 2019 The guide to getting hired, being promoted, and thriving professionally for the 40 million people of color in the workplace—fromthe CEO and cofounder of Jopwell, the leading career advancement platform for Black, Latinx, and Native American students and professionals. Let Them See You is a collection of Braswell’s straight-talking advice and mentorship for diverse careerists, from college students to mid-level professionals. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

James Baldwin: Biographical Dispatches on a Freedom Writer

DISPATCH James Baldwin: Biographical Dispatches on a Freedom Writer Phillip Luke Sinitiere Sam Houston State University Abstract This essay presents the idea of James Baldwin as a freedom writer, the organizing idea of my biography in progress. As a freedom writer, Baldwin was a revolution- ary intellectual, an essayist and novelist committed unfailingly to the realization of racial justice, interracial political equality, and economic democracy. While the book is still in process, this short essay narrates autobiographically how I came to meet and know Baldwin’s work, explains in critical fashion my work in relation to existing biographies, and reflects interpretively my thoughts- in- progress on this fascinating and captivating figure of immense historical and social consequence. Keywords: James Baldwin, biography, American culture, African- American history, black radicalism Jimmy is terrifying . Because he demands of anybody who comes in contact with him a look at some aspect of truth. How the hell do I say this?—Jimmy confronts you, not just racially, but with the human predicament. Kenneth B. Clark (1966)1 One of the last things [Baldwin] said to me was that he hoped that I and other writers would continue to be witnesses of our time; that we must speak out against institu- tionalized and individual tyranny wherever we found it. Because if left unchecked, it threated to engulf and subjugate us all—the fire this time. And, of course, he is right. He is right—about racism, violence, and cynical indifference that characterize modern society, and especially the contemporary values that are dominant here in America today. -

Copyright by Jennifer Nichole Asenas 2007

Copyright by Jennifer Nichole Asenas 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Jennifer Nichole Asenas Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Past as Rhetorical Resource for Resistance: Enabling and Constraining Memories of the Black Freedom Struggle in Eyes on the Prize Committee: Dana L. Cloud, Supervisor Larry Browning Barry Brummett Richard Cherwitz Martha Norkunas The Past as Rhetorical Resource for Resistance: Enabling and Constraining Memories of the Black Freedom Struggle in Eyes on the Prize by Jennifer Nichole Asenas, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2007 Dedication For Jeff and Marc Acknowledgements This dissertation is the product of many kind souls with brilliant minds who agreed to helped me throughout this process. I would like to thank my advisor, Dana Cloud, for being a living example of a scholar who makes a difference. I would also like to thank my committee members: Barry Brummett, Richard Cherwitz, Martha Norkunas, and Larry Browning for contributing to this project in integral and important ways. You have all influenced the way that I think about rhetoric and research. Thank you Angela Aguayo, Kristen Hoerl, and Lisa Foster for blazing trails. Jaime Wright, your inner strength is surpassed only by your kindness. Johanna Hartelius, you have reminded me how special it is to be loved. Lisa Perks, you have been a neighbor in all ways. Amanda Davis, your ability to speak truth to power is inspiring. -

Relevant Books

Relevant Books Stockley, Grif. Black Boys Burning: The 1959 Fire at the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2017, pp.210, ISBN: 1496812697. On the morning of March 5, 1959, fire had engulfed the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School in Wrightsville, thirteen miles outside of Little Rock. Forty-eight boys clawed their way through the windows of the dormitory to safety, however, twenty-one boys between the ages of thirteen and seventeen who burned to death. This book presents an explanation of how systemic poverty perpetuated by white supremacy sealed the fate of those students, hence, telling of the history of the school and fire, providing a fresh understanding of the broad implications of white supremacy. Thus, the book adds to an evolving understanding of the Jim Crow South, Arkansas’s history, the lawyers who capitalized on this tragedy, and the African American victims. Babb, Valerie. A History of the African American Novel. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp.485, ISBN: 9781107448773. This volume offers an overview of the development of the novel and its major genres. In the first part of this book, the author examines the evolution of the novel from the 1850s to the present, showing how the concept of Black identity has transformed along with the art form. The second part explores the prominent genres of African American novels, such as narratives of the enslaved, detective fiction, and speculative fiction, and considers how each one reflects changing understandings of Blackness as it builds on other literary histories by including early Black print culture, African American graphic novels, pulp fiction, and the history of adaptation of Black novels to film by placing novels in conversation with other documents - early Black newspapers and magazines, film, and authorial correspondence. -

Leni Sinclair Is the 2016 Kresge Eminent Artist

2016 KRESGE EMINENT ARTIST LENI SINC LAIR The Kresge Eminent Artist Award honors an exceptional artist in the visual, performing or literary arts for lifelong profes- sional achievements and contributions to metropolitan Detroit’s cultural community. | Leni Sinclair is the 2016 Kresge Eminent Artist. This monograph commemorates her life and work. Fred “Sonic” Smith in concert with the MC5 at Michigan State University, Lansing, Michigan, 1969. Front Cover: Dallas Hodge Band concert at Gallup Park, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1974. 5 Forward Other Voices 42 The Greatness 76 “John Sinclair” Kresge Arts in Detroit By Rip Rapson 13 Hugh “Buck” Davis of Leni Sinclair By John Lennon 108 2015-16 Kresge Arts in Detroit President and CEO 27 Bill Harris By John Sinclair Advisory Council The Kresge Foundation 35 Robin Eichele 78 A People’s History of the 47 Harvey Ovshinsky CIA Bombing Conspiracy 108 The Kresge Eminent Artist 6 Artist’s Statement 55 Peter Werbe Art (The Keith Case): Or, Award and Winners 71 Juanita Moore and Lars Bjorn 52 When Photography How the White Panthers 85 Judge Damon J. Keith is Revolution: Saved the Movement 110 About The Kresge Foundation Life 97 Rebecca Derminer Notes on Leni Sinclair By Hugh “Buck” Davis Board of Trustees 10 Leni Sinclair: Back 97 Barbara Weinberg Barefield By Cary Loren Credits In The Picture 90 Photographs: Acknowledgements By Sue Levytsky 62 Leni Sinclair: The Times 40 Coming to Amerika: Out of the Dark 22 A Reader’s Guide Leni Sinclair Chronicled Our By Herb Boyd 100 Biography Dreams and Aspirations 24 Photographs: By George Tysh 107 Our Congratulations Michelle Perron The Music Activism 68 The Evolution of Director, Kresge Arts in Detroit a Commune 107 A Note From By Leni Sinclair Richard L. -

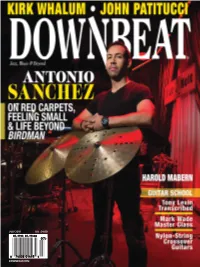

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

BOOK LIST: Race, Racism & Social Justice

BOOK LIST: Race, Racism & Social Justice All you can ever know: a memoir by Nicole Chung BIO CHUNG Bestselling memoir that examines the mysteries and complexities of the author’s transracial adoption. A chronicle of unexpected family for anyone who has struggled to figure out where they belong. America for Americans: a history of xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee 305.8 LEE Irrational fear, hatred, and hostility toward immigrants has been a defining feature of our nation. Forcing us to confront this history, Lee explains how xenophobia works, why it has endured, and how it threatens America. American poison: how racial hostility destroyed our promise by Eduardo Porter 305.8 POR A sweeping examination of how American racism has broken the country's social compact, eroded America's common goods, and damaged the lives of every American—and a heartfelt look at how these deep wounds might begin to heal. Anti racist ally: an introduction to activism & action by Sophie Williams 305.8 WIL Whether you are just finding your voice, have made a start but aren't sure what to do next, or want a fresh viewpoint, this pocket-size guide introduces and explains the language of change and shows you how to challenge the system, beginning with yourself. Begin again: James Baldwin’s America and its urgent lessons for our own by Eddie S Glaude Jr 305.8 GLA Glaude finds hope and guidance in the works of James Baldwin as he mixes biography with history, memoir, and poignant analysis of our current moment to reveal the difficult truth of racism’s continued grip on the national soul. -

African/African American Resources • 1001 Things Everyone Should Know About African American History by Jeffrey C. Steward •

African/African American Resources 1001 Things Everyone Should Know about African American History by Jeffrey C. Steward 21st Annual MLK Jr. Convocation, 2004 (VHS) 24 Reasons Why African Americans Suffer by Jimmy Dumas A Black Man's Dream: The First One Hundred Years by Bobby L. Lovett A Certain Blindness: A Black Family's Quest for the Promise of America by Paul L. Brady A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States (Vol 5: From the N.A.A.C.P. to the New Deal) edited by Hervert Aptheker A Pictorial History of Black Americans by Langston Hughes, Milton Meltzer, & C. Eric Lincoln A Profile of the Negro American by Thomas F. Pettigrew A Separate Cinema: Fifty Years of Black Cast Posters by John Kisch and Edward Mapp A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story by Elaine Brown Africa: A Biography of the Continent by John Reader Africa through the Eyes of Women Artists by Betty LaDuke Africa Counts: Number and Pattern in African Culture by Claudia Zaslavsky African Accents: Fabrics and Crafts to Decorate Your Home by Lisa Shepard African American Masters: Highlights from the Smithsonian American Art Museum curated by Gwen Everett African-American Education in DeKalb County by Narvie J. Harris & Dee Taylor African-American Life in DeKalb County, 1823-1970 by Herman "Skip" Mason, Jr. African-Americans and the Doctoral Experience: Implications for Policy by Charles V. Willie, Michael K. Grady, & Richard O. Hope African Art in Transit by Christopher B. Steiner Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience edited by Kwame Anthony Appiah & Henry Louis Gates, Jr African Sculpture by Ladislas Segy Africans in America: America's Journey through Slavery by Charles Johnson & Patricia Smith Africa's Management in the 1990's and Beyond: Reconciling Indigenous and Transplanted Institutions by Mamadou Dia After 1968: Contemporary Artists and the Civil Rights Legacy edited by Jeffrey D.