The Serengeti Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate in Svalbard 2100

M-1242 | 2018 Climate in Svalbard 2100 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation NCCS report no. 1/2019 Photo: Ketil Isaksen, MET Norway Editors I.Hanssen-Bauer, E.J.Førland, H.Hisdal, S.Mayer, A.B.Sandø, A.Sorteberg CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 Commissioned by Title: Date Climate in Svalbard 2100 January 2019 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation ISSN nr. Rapport nr. 2387-3027 1/2019 Authors Classification Editors: I.Hanssen-Bauer1,12, E.J.Førland1,12, H.Hisdal2,12, Free S.Mayer3,12,13, A.B.Sandø5,13, A.Sorteberg4,13 Clients Authors: M.Adakudlu3,13, J.Andresen2, J.Bakke4,13, S.Beldring2,12, R.Benestad1, W. Bilt4,13, J.Bogen2, C.Borstad6, Norwegian Environment Agency (Miljødirektoratet) K.Breili9, Ø.Breivik1,4, K.Y.Børsheim5,13, H.H.Christiansen6, A.Dobler1, R.Engeset2, R.Frauenfelder7, S.Gerland10, H.M.Gjelten1, J.Gundersen2, K.Isaksen1,12, C.Jaedicke7, H.Kierulf9, J.Kohler10, H.Li2,12, J.Lutz1,12, K.Melvold2,12, Client’s reference 1,12 4,6 2,12 5,8,13 A.Mezghani , F.Nilsen , I.B.Nilsen , J.E.Ø.Nilsen , http://www.miljodirektoratet.no/M1242 O. Pavlova10, O.Ravndal9, B.Risebrobakken3,13, T.Saloranta2, S.Sandven6,8,13, T.V.Schuler6,11, M.J.R.Simpson9, M.Skogen5,13, L.H.Smedsrud4,6,13, M.Sund2, D. Vikhamar-Schuler1,2,12, S.Westermann11, W.K.Wong2,12 Affiliations: See Acknowledgements! Abstract The Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS) is collaboration between the Norwegian Meteorological In- This report was commissioned by the Norwegian Environment Agency in order to provide basic information for use stitute, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Norwegian Research Centre and the Bjerknes in climate change adaptation in Svalbard. -

Spitsbergen-Bear Island

SPITSBERGEN-BEAR ISLAND A voyage to Bear Island and returning to Longyeabyen, in search of seals and bears. The land of the midnight sun, of snow and ice, offers some of the finest scenery and wildlife experiences in the world. Bear Island, or Bjørnøya in Norwegian, is the southernmost island of the Spitsbergen archipelago. ITINERARY Day 1: Departure from Longyearbyen Arrive in Longyearbyen, the administrative capital of the Spitsbergen archipelago of which West Spitsbergen is the largest island. Before embarking there is an opportunity to stroll around this former mining town, whose parish church and Polar Museum are well worth visiting. In the early evening the ship will sail out of Isfjorden. Day 2: Cruising the fjords of Hornshund 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com We start the day quietly cruising the side fjords of the amphitheatre of glacier fronts. spectacular Hornsund area of southern Spitsbergen, enjoying the scenery of towering mountain peaks. Hornsundtind rises to Day 7: Stormbukta 1,431m, while Bautaen shows why early Dutch explorers gave If ice conditions allow we will land at Stormbukta with an easily the name ‘Spitsbergen’ - pointed mountains - to the island. accessible Kittiwake colony in a canyon and warm springs, There are also 14 magnificent glaciers in the area and very which do not freeze during winter. Alternatively we land at good chances of encounters with seals and Polar Bear. Palfylodden a Walrus haul out place with the remains of thousands of walruses slaughtered in previous centuries. We Day 3: Hvalrossbukta sail northward along the Spitsbergen banks, looking for Finn At the south side of Bear Island we sail by the largest bird cliffs Whales. -

Svalbard's Risk of Russian Annexation

The Coldest War: Svalbard's Risk of Russian Annexation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Vlasman, Savannah. 2019. The Coldest War: Svalbard's Risk of Russian Annexation. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004069 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Coldest War: Svalbard’s Risk of Russian Annexation Savannah Vlasman A Thesis In the Field of International Relations for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University 2018 Savannah Vlasman Copyright 2018 Abstract Svalbard is a remote Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, home to the northernmost permanent human settlement. This paper investigates Russia’s imperialistic interest in Svalbard and examines the likelihood of Russia annexing Svalbard in the near future. The examination reveals Svalbard is particularly vulnerable at present due to melting sea ice, rising oil prices, and escalating tension between Russia and the West. Through analyzing the past and present of Svalbard, Russia’s interests in the territory, and the details of the Svalbard Treaty, it became evident that a Russian annexation is plausible if not probable. An assessment of Russia’s actions in annexing Crimea, as well as their legal justifications, reveals that these same arguments could be used in annexing Svalbard. -

2019 Wild Norway & Svalbard Field Report

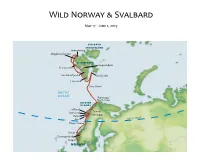

Wild Norway & Svalbard May 17 - June 2, 2019 SVALBARD ARCHIPELAGO Smeerenburg Magdalenefjorden SPITSBERGEN Longyearbyen Poolepynten Van Mijenfjorden Storfjorden Hornsund Bear Island ARCTIC OCEAN Skarsvaag/ North Cape LOFOTEN ISLANDS Trollfjord Stamsund Tromsø Kjerringøy Reine CLE Røst ARCTIC CIR Husey/Sanna Runde Geirangerfjord Bergen NORWAY Sunday, May 19, 2019 Bergen, Norway / Embark Ocean Adventurer Unusual for Bergen, it was a dry, warm, and sunny weekend when we arrived here to begin our travels in Wild Norway and Svalbard. Bergen experiences only five rain-free days a year, and this exceptional weather was being fully enjoyed by the locals, especially as this was also the Norwegian National Day holiday weekend. We set out on foot early this morning, for a tour of the old wharf-side district of Bryggen with its picturesque and higgledy-piggledy medieval wooden houses, their colorful gables lit up by today’s bright sunshine. Next, we boarded coaches which took us to Troldhaugen, the home of Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg for over 20 years. The hut where he did much of his work still stands on the lakeside at the foot of the garden. We were treated to an excellent piano recital of some of Grieg’s music before we went to lunch. All too soon, it was time to return to Bergen where our home for the next two weeks, the Ocean Adventurer, awaited us. Once settled in our cabins, our Expedition Leader, John Yersin, introduced us to his team of Zodiac drivers and lecturers who would be accompanying us on our journey over the next two weeks. -

The Norwegian Fjords, Bear Island & Svalbard

SVALBARDTHE NORWEGIAN FJORDS, BEAR ISLAND & SVALBARD - SPRINGTIME IN SVALBARD - SVALBARD 2 ADVENTURE021 - EXPEDITION SVALBARD POLAR ADVENTURES SINCE 1999 For more than 20 years, we have taken adventurous travellers to the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard. From May to September, our three small expedition ships explore this magnificent wilderness that are home to animals such as the charming walrus, the cute Arctic fox, the endemic Svalbard reindeer and last, but certainly not least, the king of the Arctic – the polar bear. Every expedition with us is unique and our aim is that each passenger will have the trip of a lifetime. When you call our office you will speak to members of staff, whom all have been to Svalbard themselves and can answer all your questions about the big adventure. Sustainability is at the heart of PolarQuest and all trips are climate compensated. Welcome on board! SMALL EXPEDITION SHIPS – GREAT MOMENTS Our expedition ships are comfortable, carry only 12 or 53 passengers and when you travel through Svalbard’s untamed wilderness as the exact route offer a completely different experience compared to a larger ship. We can depends on weather, ice conditions and wildlife encounters. Sometimes you reach some of the most inaccessible areas, all passengers can go ashore might be woken up in the middle of the bright night if a polar bear has been at the same time and we can maximise the time to ensure that you get the spotted on the ice or a whale in front of the ship. Below, please find our most out of your trip. -

The Disputed Maritime Zones Around Svalbard

THE DISPUTED MARITIME ZONES AROUND SVALBARD Robin Churchill and Geir Ulfstein* Abstract Before the First World War the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard was a terra nullius. Under a treaty of 1920 Norway’s sovereignty over Svalbard was recognised, while the other States parties to the Treaty were accorded equal rights to carry on certain economic activities, including fishing and mining, in Svalbard’s territorial waters. By virtue of its sovereignty, Norway is entitled to establish the full range of maritime zones in respect of Svalbard. It has established a 12-mile territorial sea and a 200-mile fishery protection zone (rather than an Exclusive Economic Zone) around Svalbard. Svalbard also has a continental shelf, extending beyond 200 miles in places. The Norwegian government argues that the equal rights of fishing and mining do not apply beyond the territorial sea, whereas a number of other States parties take the opposite view. This paper examines both sets of arguments, and reaches the conclusion that there is no clear-cut answer to the question. The final part of the paper suggests various ways in which the dispute between Norway and other States parties over the geographical application of the Treaty could be resolved. * Robin Churchill is professor of international law at the University of Dundee, United Kingdom. Prior to his move to Dundee in 2006, he was for many years a member of staff at Cardiff Law School, also in the United Kingdom. His research interests include the international law of the sea, international environmental law, EU fisheries law and international human rights, on the first three of which he has written widely. -

1 the Status Under International Law of the Maritime Areas Around

Paper read at the Symposium on “Politics and Law – Energy and Environment in the Far North,” held at the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters on 24 January 2007 The Status under International Law of the Maritime Areas around Svalbard D. H. Anderson My subject is the status of the maritime areas in the High North, and the interpretation of the Spitsbergen Treaty of 1920 after 87 Years. The subject has been a source of controversy since 1970: how to interpret and apply the Spitsbergen Treaty in the light of the developments in the law of the sea? My views differ in some respects from those previously set out by Norwegian Government. As a guest here, I will try to explain my thinking and to do so in diplomatic terms. In 1900, the archipelago was terra nullius and uncertainties arose, e.g. over coal mining. Under international law, sovereignty over terra nullius is normally acquired by means of peaceful occupation and administration. Norway’s sovereignty was acquired in a different way. Sovereignty was conferred on Norway by a collective decision of a number of states. This decision was cast in the form of a Treaty. According to the British White Paper, the title of the instrument was “Treaty concerning the Status of Spitsbergen and conferring the Sovereignty on Norway.”1 The Treaty did two things: it defined and regulated a new status for the archipelago and it conferred sovereignty on Norway. The Treaty opened the way for Norway to assume administration and ended the previous uncertainties when it entered into force This paper contains personal opinions that do not engage any institution with which the writer was previously associated. -

Giant Maps Europe

KILOMETERS KILOMETERS 70° 55° 50°W 45° 40° 80° 35° 30° 25° 20° 15° 10° 5°W 0° 5°E 10° 15° 20° 25° 30° 35° 40° 45° 50° 55° 60° 65° 70° 75° 80° 85° 90° 95°E 100°E 400 300 200 100 400 300 200 100 0 0 75° 80° 75° 70° STATUTE MILES STATUTE STATUTE MILES STATUTE Ostrova Belaya Zemlya A 400 300 200 100 400 300 200 100 0 0 Ostrov Rudolph AZIMUTHAL EQUIDISTANT PROJECTION EQUIDISTANT AZIMUTHAL AZIMUTHAL EQUIDISTANT PROJECTION EQUIDISTANT AZIMUTHAL Ost Ostrov Graham rov Bell Ostrov Vize (London) J No shoes or writing utensils on map on utensils writing or shoes No ack son Meridian of Greenwich E Zemlya Wilczek n E NE W A Ostrov N NW D A N a Salisbury F Arctic Ocean Ostrov Hall I SE SW r S e O I D) c c S NW N Ostrov Arthur N t E Ostrov A S S O A NE ) i S T c Zemlya George Hooker T L SW N F W SE E E A 55° 65° A R A S A Burkhta Tikhaya F J O 65° Zemlya Alexandra A Y Z Russia L N L A N Sjuøyane E M F R U Z ( Ostrov Victoria N Lågøya Kvitøya N Storøya D T Danskøya R A I Nordaustlandet 95°E C E L Denmark A Nuuk L B Ny Ålesund A (Godth˚ab) E A E L Spitsbergen Norway Kongsøya R 50° A Prins Karls Forland Svenskøya Y L A Kong Karls R L Longyearbyen Barentsøya Land Ostrov Pankrat'yeva A E V Barentsburg E K A M A ( S G E Edgeøya S E D Z 90° K N A A Sørkappøya Hopen L E A 45° S Y N E L S C A IR E T C E N IC T E V E C B A R R A R O A R C T IC G Bjørnøya N C IR (Bear Island) 85° C L E E D e Ostrov n m a r k Belush'ya Guba S t Vaygach r a i 60° 40° t Jan Mayen E Norway Ostrov Mezhdusharskiy Vorkuta 60° A a y E h Cape a Nort k B s r N S H Berlev˚ag Kolguyev ' Ob e a E Island 80° iða i S mm l Ob fj l´o ør e e örð f øy rf a A ur na a es a E u´ Lop t E Varanger Pen. -

The Longyearbyen Dilemma Torbjørn Pedersen* Nord University, Faculty of Social Sciences

Arctic Review on Law and Politics Vol. 8, 2017, pp. 95Á108 The Politics of Presence: The Longyearbyen Dilemma Torbjørn Pedersen* Nord University, Faculty of Social Sciences Abstract The significant presence of Norwegian citizens in Svalbard has subdued the misperception that Norway’s northernmost territory has an international or internationalized legal status. Now this Norwegian presence in the archipelago is about to change. Amid tumbling coal prices, the state- owned mining company Store Norske has shrunk to a minimum, and no current or proposed business in Longyearbyen has the potential to compensate for the loss of Norwegian workers, in part due to their international character and recruitment policies. This study argues that the likely further dilution of Norwegians in Longyearbyen may ultimately fuel misperceptions about the legal status of Svalbard and pose new foreign and security policy challenges to Norway. Keywords: Arctic; foreign policy; international law; International Relations Theory; Longyearbyen; presence; sovereignty; Svalbard Responsible Editor: Øyvind Ravna, UiT- The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway. Received: January 2017; Accepted: June 2017; Published: August 2017 1. Introduction At 788 North, the settlement of Longyearbyen marks Norway’s resolve to assert sovereignty over Svalbard, a group of islands scattered roughly halfway between the Norwegian mainland and the North Pole. The settlement of approx. 2,000 inhabitants is a family-based society and features a 2,200-meter paved airstrip, a deep-sea port, hotels, fine-dining restaurants, cafes, kindergartens, a school, a grocery store, and numerous sports equipment stores. For decades, the Norwegian government has stressed the importance of having a substantial presence in these islands littoral to the Arctic Ocean.1 In a policy document issued in 2010, for instance, the government stated that ‘‘it is the Government’s position that the assertion of Norwegian sovereignty is best served with a permanent presence of Norwegian citizens. -

Soviet Union: Military Plane Crashes in Norway

Use your browser's Print command to print this page. Use your browser's Back command to go back to the original article and continue work. Issue Date: October 27, 1978 Soviet Union: Military Plane Crashes in Norway The crash of a Soviet military reconnaissance aircraft on a remote Norwegian island in August strained Soviet-Norwegian relations during October. A Norwegian investigating team began October 12 to transcribe the contents of the aircraft's flight recorder (the so-called black box) over vehement objections from Moscow. The plane, an early model TU-16, had disappeared August 28 in the waters off Hopen Island, southeast of Spitsbergen. Wreckage from the crash was discovered two days later by a four-man Norwegian weather-forecasting team, who were the only inhabitants of Hopen. A subsequent search by Norwegian investigators recovered the bodies of the seven Soviet crewmen of the TU-16 and its flight recorder. The aircraft was identified as a reconnaissance craft used by the Soviet naval command at its base in Murmansk. Moscow had refused to acknowledge that one of its aircraft had crashed until the bodies of the crew were turned over to Soviet authorities. When Norway announced that it had recovered the flight recorder and intended to open it, Moscow delivered a protest note to Oslo calling the opening of the black box an "unfriendly action." The protest note was made public October 6 by the Norwegian Foreign Ministry. Norway asserted that it was legally entitled to open the black box, since the TU-16 had crashed on its territory. -

THE DISPUTED MARITIME ZONES AROUND SVALBARD Robin

THE DISPUTED MARITIME ZONES AROUND SVALBARD Robin Churchill and Geir Ulfstein* Abstract Before the First World War the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard was a terra nullius. Under a treaty of 1920 Norway’s sovereignty over Svalbard was recognised, while the other States parties to the Treaty were accorded equal rights to carry on certain economic activities, including fishing and mining, in Svalbard’s territorial waters. By virtue of its sovereignty, Norway is entitled to establish the full range of maritime zones in respect of Svalbard. It has established a 12-mile territorial sea and a 200-mile fishery protection zone (rather than an Exclusive Economic Zone) around Svalbard. Svalbard also has a continental shelf, extending beyond 200 miles in places. The Norwegian government argues that the equal rights of fishing and mining do not apply beyond the territorial sea, whereas a number of other States parties take the opposite view. This paper examines both sets of arguments, and reaches the conclusion that there is no clear-cut answer to the question. The final part of the paper suggests various ways in which the dispute between Norway and other States parties over the geographical application of the Treaty could be resolved. * Robin Churchill is professor of international law at the University of Dundee, United Kingdom. Prior to his move to Dundee in 2006, he was for many years a member of staff at Cardiff Law School, also in the United Kingdom. His research interests include the international law of the sea, international environmental law, EU fisheries law and international human rights, on the first three of which he has written widely. -

The Svalbard Treaty and Norwegian Sovereignty Øystein Jensen University of South-Eastern Norway and Fridtjof Nansen Institute, Norway

Arctic Review on Law and Politics Peer-reviewed article Vol. 11, 2020, pp. 82–107 The Svalbard Treaty and Norwegian Sovereignty Øystein Jensen University of South-Eastern Norway and Fridtjof Nansen Institute, Norway Abstract A hundred years ago on 9 February 2020, the Svalbard Treaty was adopted in Paris, granting Norway her long-standing ambition: full and absolute sovereignty over the Svalbard archipelago. After a brief review of the negotiations that preceded the Paris decision, this article examines the main elements of the Treaty: Norwegian sovereignty, the principle of non-discrimination and the terra nullius rights of other states, peaceful utilization, scientific research and environmental protection. Focus then shifts to Norway’s policy towards Svalbard and the implementation of the Treaty’s provisions: what have been the main lines of Norwegian Svalbard politics; what adminis- trative structures have evolved; to what extent has Norwegian legislation been made applicable to Svalbard? Importantly, the article also addresses how widespread changes in international law that have taken place since 1920, particularly developments concerning the law of the sea, have brought to the forefront controversial issues concerning the geographic scope of the Treaty’s application. Keywords: Svalbard Treaty, sovereignty, non-discrimination, law of the sea Responsible Editor: Nigel Bankes, Faculty of Law, University of Calgary, Canada Received: May 2020; Accepted: June 2020; Published: December 2020 1 Introduction The year 2020 marks a milestone in Norwegian polar history: on 9 February it was 100 years since the Treaty concerning the Archipelago of Spitsbergen (hereafter: Svalbard Treaty) was adopted in Paris.1 The Treaty recognizes Norway sovereignty over the Svalbard archipelago – all islands, islets and reefs between 74° and 81° N and 10° and 35° E.