Terra Nullius and the Svalbard Question: Exploring an Anomaly in International Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict on the Right to Use Mineral Resources on Svalbard – an Outline

Annuals of the Administration and Law no. 17 (1), p. 233-247 Original article Received: 25.03.2017 Accepted: 05.05.2017 Published: 30.06.2017 Funding sources for the publication: Humanitas University Authors’ Contribution: (A) Study Design (B) Data Collection (C) Statistical Analysis (D) Data Interpretation (E) Manuscript Preparation (F) Literature Search Dariusz Rozmus* The Arctic – the place of the future1 CONFLICT ON THE RIGHT TO USE MINERAL RESOURCES ON SVALBARD – AN OUTLINE INTRODUCTION The subject of the article is a legal dispute between Norway and other states about the possibility of conducting mining operations on the continental shelf around the islands of Svalbard2. It is mainly about the possibility to extract liquid * Dr hab.; The Department of Administration and Management Humanitas University in Sosnowiec. 1 A. and C. Centkiewiczowie, Arktyka kraj przyszłości, Warszawa 1954 (the above mentioned motto can be repeated constans). 2 The Svalbard archipelago consists of a number of islands located in the Arctic. There is little over 1000 km to the North pole. Older literature used the name Spitsbergen for the above archipelago. The term is derived from one of the largest islands, i.e. West Spitsbergen - Vestspitsbergen. The archipelago consists of the following islands: West Spitsbergen (37,673 km²), Northwestern Land (Nordaustlandet, 14,443 km²), Edge’s Island (Edgeøya, 5074 km²), Barents’s Island (Barentsøya, 1250 km²), White Island (Kvitøya, 682 km²), Prince Charles Island (Prins Karl Forland, 615 km²), Royal Island (Kongsøya, 191 km²), Bjørnøya, 178 km², Swedish Island (Svenskøya, 137 km²), Wilhelmøya, (120 km²), Hopen 234 ANNUALS OF THE ADMINISTRATION AND LAW. -

Climate in Svalbard 2100

M-1242 | 2018 Climate in Svalbard 2100 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation NCCS report no. 1/2019 Photo: Ketil Isaksen, MET Norway Editors I.Hanssen-Bauer, E.J.Førland, H.Hisdal, S.Mayer, A.B.Sandø, A.Sorteberg CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 Commissioned by Title: Date Climate in Svalbard 2100 January 2019 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation ISSN nr. Rapport nr. 2387-3027 1/2019 Authors Classification Editors: I.Hanssen-Bauer1,12, E.J.Førland1,12, H.Hisdal2,12, Free S.Mayer3,12,13, A.B.Sandø5,13, A.Sorteberg4,13 Clients Authors: M.Adakudlu3,13, J.Andresen2, J.Bakke4,13, S.Beldring2,12, R.Benestad1, W. Bilt4,13, J.Bogen2, C.Borstad6, Norwegian Environment Agency (Miljødirektoratet) K.Breili9, Ø.Breivik1,4, K.Y.Børsheim5,13, H.H.Christiansen6, A.Dobler1, R.Engeset2, R.Frauenfelder7, S.Gerland10, H.M.Gjelten1, J.Gundersen2, K.Isaksen1,12, C.Jaedicke7, H.Kierulf9, J.Kohler10, H.Li2,12, J.Lutz1,12, K.Melvold2,12, Client’s reference 1,12 4,6 2,12 5,8,13 A.Mezghani , F.Nilsen , I.B.Nilsen , J.E.Ø.Nilsen , http://www.miljodirektoratet.no/M1242 O. Pavlova10, O.Ravndal9, B.Risebrobakken3,13, T.Saloranta2, S.Sandven6,8,13, T.V.Schuler6,11, M.J.R.Simpson9, M.Skogen5,13, L.H.Smedsrud4,6,13, M.Sund2, D. Vikhamar-Schuler1,2,12, S.Westermann11, W.K.Wong2,12 Affiliations: See Acknowledgements! Abstract The Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS) is collaboration between the Norwegian Meteorological In- This report was commissioned by the Norwegian Environment Agency in order to provide basic information for use stitute, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Norwegian Research Centre and the Bjerknes in climate change adaptation in Svalbard. -

University of Copenhagen FACULTY of SOCIAL SCIENCES Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY of COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3

Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Jacobsen, Marc Publication date: 2019 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Jacobsen, M. (2019). Arctic identity interactions: Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies. Download date: 11. okt.. 2021 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE university of copenhagen FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES faculty of social sciences UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN · DENMARK PHD DISSERTATION 2019 · ISBN 978-87-7209-312-3 MARC JACOBSEN Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies and Denmark’s Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s identity interactions Arctic Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies PhD Dissertation 2019 Marc Jacobsen Arctic identity interactions Reconfiguring dependency in Greenland’s and Denmark’s foreign policies Marc Jacobsen PhD Dissertation Department of Political Science University of Copenhagen September 2019 Main supervisor: Professor Ole Wæver, University of Copenhagen. Co-supervisor: Associate Professor Ulrik Pram Gad, Aalborg University. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

British Columbia 1858

Legislative Library of British Columbia Background Paper 2007: 02 / May 2007 British Columbia 1858 Nearly 150 years ago, the land that would become the province of British Columbia was transformed. The year – 1858 – saw the creation of a new colony and the sparking of a gold rush that dramatically increased the local population. Some of the future province’s most famous and notorious early citizens arrived during that year. As historian Jean Barman wrote: in 1858, “the status quo was irrevocably shattered.” Prepared by Emily Yearwood-Lee Reference Librarian Legislative Library of British Columbia LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BACKGROUND PAPERS AND BRIEFS ABOUT THE PAPERS Staff of the Legislative Library prepare background papers and briefs on aspects of provincial history and public policy. All papers can be viewed on the library’s website at http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/ SOURCES All sources cited in the papers are part of the library collection or available on the Internet. The Legislative Library’s collection includes an estimated 300,000 print items, including a large number of BC government documents dating from colonial times to the present. The library also downloads current online BC government documents to its catalogue. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the Legislative Library or the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. While great care is taken to ensure these papers are accurate and balanced, the Legislative Library is not responsible for errors or omissions. Papers are written using information publicly available at the time of production and the Library cannot take responsibility for the absolute accuracy of those sources. -

UK and Colonies

This document was archived on 27 July 2017 UK and Colonies 1. General 1.1 Before 1 January 1949, the principal form of nationality was British subject status, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the Crown's dominions. On and after this date, the main form of nationality was citizenship of the UK and Colonies, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the UK and Colonies. 2. Meaning of the expression 2.1 On 1 January 1949, all the territories within the Crown's dominions came within the UK and Colonies except for the Dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, India, Pakistan and Ceylon (see "DOMINIONS") and Southern Rhodesia, which were identified by s.1(3) of the BNA 1948 as independent Commonwealth countries. Section 32(1) of the 1948 Act defined "colony" as excluding any such country. Also excluded from the UK and Colonies was Southern Ireland, although it was not an independent Commonwealth country. 2.2 For the purposes of the BNA 1948, the UK included Northern Ireland and, as of 10 February 1972, the Island of Rockall, but excluded the Channel Islands and Isle of Man which, under s.32(1), were colonies. 2.3 The significance of a territory which came within the UK and Colonies was, of course, that by virtue of a connection with such a territory a person could become a CUKC. Persons who, prior to 1 January 1949, had become British subjects by birth, naturalisation, annexation or descent as a result of a connection with a territory which, on that date, came within the UK and Colonies were automatically re- classified as CUKCs (s.12(1)-(2)). -

ESG Perspectives June 2019 Svalbard Sojourn an Arctic

June 2019 ESG Perspectives ™ SVALBARD SOJOURN: AN ARCTIC EXPERIENCE by Bob Smith, President & CIO islands are 60% glaciated with some of the world’s fastest-moving glaciers. The balance of the region is 30% barren ground, and 10% is covered with very low ground vegetation. In contrast to other Arctic regions, the Svalbard has no indigenous population and there is no historical evidence that the Vikings settled in the area during their time. In fact, it was the 1596 Dutch expedition of Willem Barents who discovered and drew maps of the region before his ship was crushed by freezing sea ice leading to his untimely death. However, the work of this expedition survived, and it led to the exploration of the region by other European countries over the Photo of Bob Smith in Kungsfjord, Svalbard centuries. This eventually gave rise to the exploitation It is said that what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay of the natural resources of the region as a destination in the Arctic. That is because this region provides for whalers, fur trappers, and seal hunters, as well as essential global climate regulation and substantial other animal-based products. With the industrialization ecosystem benefits to humanity outside and beyond of Europe and the arrival of steel-hulled ships in the its boundaries. Indeed, the Arctic environment, and early 1900s, this region also eventually became a source human society and its economic activities are deeply for industrial minerals and, in particular, coal. connected to each other, representing a pivotal link in a complex adaptive global ecosystem. -

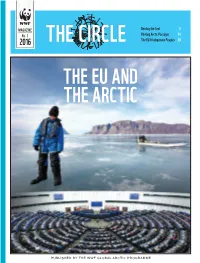

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

Written Exam SH-201 the History of Svalbard the University Centre in Svalbard, Monday 6 February 2012

Written exam SH-201 The History of Svalbard The University Centre in Svalbard, Monday 6 February 2012 The exam is a 3 hour written test. It consists of two parts: Part I is a multiple choice test of factual knowledge. Note: This sheet with answers to part I shall be handed in. Part II (see below) is an essay part where you write extensively about one of two alternative subjects. No aids except dictionary are permitted. You may answer in English, Norwegian, Swedish or Danish. 1 2 Part I counts approximately /3 and part II counts /3 of the grade at the evaluation, but adjustment may take place. Both parts must be passed in order to pass the whole exam. Part I: Multiple choice test. Make only one cross for each question. In what year was Bjørnøya discovered by Willem 1. 1569 1596 1603 Barentsz? 2. When did land-based whaling end on Svalbard? ca. 1630 ca. 1680 ca. 1720 Which geographical region did most Russian 3. Pechora Murmansk White Sea hunters and trappers come from? When did Norwegian hunters and trappers start 4. ca. 1700 the 1750s the 1820s going to Svalbard regularly? From when dates the first map to show the whole 5. 1598 1714 1872 Svalbard archipelago? A famous scientific expedition visited Svalbard in 6. Chichagov Fram 1838–39. Which name is it known under? Recherche Svalbard was for a long time a no man’s land. In 7. Norway Sweden Russia 1871, who took an initiative to annex the islands? 8. When did Norway formally take over sovereignty? 1916 1920 1925 When was the Sysselmann (Governor of Svalbard) 9. -

Reputations on the Line in Van Diemen's Land

REPUTATIONS ON THE LINE IN VAN DIEMEN’S LAND: a dissertation on the general theme of the Rule of Law as it emerged in a young penal colony with particular emphasis on the law of defamation by ROSEMARY CONCHITA LUCADOU-WELLS LLB., (Queensland), B.Ed., (Tasmania), MA., (Murdoch), PhD., (Deakin) This thesis is presented for the degree of Master of Laws of Murdoch University, 2012. I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Rosemary Conchita Lucadou-Wells ABSTRACT This research focuses on the development of the jurisprudence of the infant colony of Van Diemen’s Land now known as Tasmania, with particular interest on the law of defamation. During the first thirty years of this British penal colony its population was subject to changes. There were the soldiery, who provided the basis of government headed by a Lieutenant Governor, the indigenous people, the convicts, and gradually an influx of settlers who came enthused by governmental promises of grants of land. In addition to these free settlers there were a selection of convicts who, under a process of something akin to manumission under Roman Law, became upon completion of their sentence, eligible for freedom and possibly a grant of land. There developed a spirit of competition amongst the settlers, each wanted to become more successful than the others. The favourite means of distinguishing oneself was the uttering or publication of damaging words against a person who was perceived to be a rival.