Organised Phonology Data Supplement Wuvulu Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

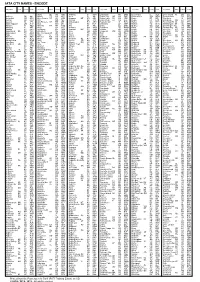

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB -

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea N.B. To check the official, current database of IATA Codes see: http://www.iata.org/publications/Pages/code-search.aspx City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Afore AFR Afore Airstrip Agaun AUP Aiambak AIH Aiambak Aiome AIE Aiome Aitape ATP Aitape Aitape TAJ Tadji Aiyura Valley AYU Aiyura Alotau GUR Ama AMF Ama Amanab AMU Amanab Amazon Bay AZB Amboin AMG Amboin Amboin KRJ Karawari Airstrip Ambunti AUJ Ambunti Andekombe ADC Andakombe Angoram AGG Angoram Anguganak AKG Anguganak Annanberg AOB Annanberg April River APR April River Aragip ARP Arawa RAW Arawa City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Arona AON Arona Asapa APP Asapa Aseki AEK Aseki Asirim ASZ Asirim Atkamba Mission ABP Atkamba Aua Island AUI Aua Island Aumo AUV Aumo Babase Island MKN Malekolon Baimuru VMU Baindoung BDZ Baindoung Bainyik HYF Hayfields Balimo OPU Bambu BCP Bambu Bamu BMZ Bamu Bapi BPD Bapi Airstrip Bawan BWJ Bawan Bensbach BSP Bensbach Bewani BWP Bewani Bialla, Matalilu, Ewase BAA Bialla Biangabip BPK Biangabip Biaru BRP Biaru Biniguni XBN Biniguni Boang BOV Bodinumu BNM Bodinumu Bomai BMH Bomai Boridi BPB Boridi Bosset BOT Bosset Brahman BRH Brahman 2 City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Buin UBI Buin Buka BUA Buki FIN Finschhafen Bulolo BUL Bulolo Bundi BNT Bundi Bunsil BXZ Cape Gloucester CGC Cape Gloucester Cape Orford CPI Cape Rodney CPN Cape Rodney Cape Vogel CVL Castori Islets DOI Doini Chungribu CVB Chungribu Dabo DAO Dabo Dalbertis DLB Dalbertis Daru DAU Daup DAF Daup Debepare DBP Debepare Denglagu Mission -

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Catalogue of South Seas

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Room 4201, Coombs Building College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia Telephone: (612) 6125 2521 Fax: (612) 6125 0198 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pambu Catalogue of South Seas Photograph Collections Chronologically arranged, including provenance (photographer or collector), title of record group, location of materials and sources of information. Amended 18, 30 June, 26 Jul 2006, 7 Aug 2007, 11 Mar, 21 Apr, 21 May, 8 Jul, 7, 12 Aug 2008, 8, 20 Jan 2009, 23 Feb 2009, 19 & 26 Mar 2009, 23 Sep 2009, 19 Oct, 26, 30 Nov, 7 Dec 2009, 26 May 2010, 7 Jul 2010; 30 Mar, 15 Apr, 3, 28 May, 2 & 14 Jun 2011, 17 Jan 2012. Date Provenance Region Record Group & Location &/or Source Range Description 1848 J. W. Newland Tahiti Daguerreotypes of natives in Location unknown. Possibly in South America and the South the Historic Photograph Sea Islands, including Queen Collection at the University of Pomare and her subjects. Ref Sydney. (Willis, 1988, p.33; SMH, 14 Mar.1848. and Davies & Stanbury, 1985, p.11). 1857- Matthew New Guinea; Macarthur family albums, Original albums in the 1866, Fortescue Vanuatu; collected by Sir William possession of Mr Macarthur- 1879 Moresby Solomon Macarthur. Stanham. Microfilm copies, Islands Mitchell Library, PXA4358-1. 1858- Paul Fonbonne Vanuatu; New 334 glass negatives and some Mitchell Library, Orig. Neg. Set 1933 Caledonia, prints. 33. Noumea, Isle of Pines c.1850s- Presbyterian Vanuatu Photograph albums - Mitchell Library, ML 1890s Church of missions. -

Marsupials and Rodents of the Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea Front Cover: a Recently Killed Specimen of an Adult Female Melomys Matambuai from Manus Island

Occasional Papers Museum of Texas Tech University Number xxx352 2 dayNovember month 20172014 TITLE TIMES NEW ROMAN BOLD 18 PT. MARSUPIALS AND RODENTS OF THE ADMIRALTY ISLANDS, PAPUA NEW GUINEA Front cover: A recently killed specimen of an adult female Melomys matambuai from Manus Island. Photograph courtesy of Ann Williams. MARSUPIALS AND RODENTS OF THE ADMIRALTY ISLANDS, PAPUA NEW GUINEA RONALD H. PINE, ANDREW L. MACK, AND ROBERT M. TIMM ABSTRACT We provide the first account of all non-volant, non-marine mammals recorded, whether reliably, questionably, or erroneously, from the Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea. Species recorded with certainty, or near certainty, are the bandicoot Echymipera cf. kalubu, the wide- spread cuscus Phalanger orientalis, the endemic (?) cuscus Spilocuscus kraemeri, the endemic rat Melomys matambuai, a recently described species of endemic rat Rattus detentus, and the commensal rats Rattus exulans and Rattus rattus. Species erroneously reported from the islands or whose presence has yet to be confirmed are the rats Melomys bougainville, Rattus mordax, Rattus praetor, and Uromys neobrittanicus. Included additional specimens to those previously reported in the literature are of Spilocuscus kraemeri and two new specimens of Melomys mat- ambuai, previously known only from the holotype and a paratype, and new specimens of Rattus exulans. The identity of a specimen previously thought to be of Spilocuscus kraemeri and said to have been taken on Bali, an island off the coast of West New Britain, does appear to be of that species, although this taxon is generally thought of as occurring only in the Admiralties and vicinity. Summaries from the literature and new information are provided on the morphology, variation, ecology, and zoogeography of the species treated. -

Download 676.32 KB

Social Safeguard Monitoring Report Semi-annual Report September 2020 Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Reporting period covering January-June 2020. Prepared by National Maritime Safety Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This semi-annual social monitoring report is a document of the Borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. National Maritime Safety Authority Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Project Number: 44375-013 Loan Number: 2978-PNG: Maritime and Waterways Safety Project Social Safeguard Monitoring Report Period Covering: January – June 2020 Prepared by: National Maritime Safety Authority September 2020 2 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1. PROJECT OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................... 6 2. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 361. National Seas Act 1977. Certified On: / /20

Chapter 361. National Seas Act 1977. Certified on: / /20 . INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA. Chapter 361. National Seas Act 1977. ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. PART I – PRELIMINARY. 1. Interpretation. “baseline” “low water elevation” “low water line” “miles” PART II – TERRITORIAL SEA. 2. Description of territorial sea. 3. Location of limits of territorial sea. 4. Baselines where no determination made. PART III – INTERNAL WATERS. 5. Description of internal waters. PART IV – OFFSHORE SEAS. 6. Description of offshore seas. PART V – ARCHIPELAGIC WATERS. 7. Description of archipelagic waters. “associated feature” “feature of the coastline” “low water point” “the Nukumanu Islands Archipelago” “the Tauu Islands Archipelago” PART VI – MISCELLANEOUS. 8. Location of lines in cases of doubt. PART VII – TRANSITIONAL. 9. Interim delimitation of archipelagic waters. SCHEDULE 1 – Principles for ascertaining baselines. SCHEDULE 2 – Interim delimitation of archipelagic waters. INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA. AN ACT entitled National Seas Act 1977, Being an Act to describe and provide for the demarcation of– (a) the territorial sea; and (b) the internal waters; and (c) the offshore seas; and (d) the archipelagic waters, for the purpose of asserting the rights of the State in relation to those areas. PART I. – PRELIMINARY. 1. INTERPRETATION. (1) In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears– “baseline” means territorial sea baseline; “low water elevation” means a naturally formed area of land surrounded by and above water at mean low water springs but submerged at high water; “low water line” means the low water line at mean low water springs; “miles” means international nautical miles. (2) For the purposes of this Act– (a) the eastern part of the island of New Guinea; and (b) each island under the sovereignty of the State, shall be deemed to have a separate continuous baseline. -

National Seas Act 1977

136 INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA. CHAPTER No. 361. National Seas. GENERAL ANNOTATION. ADMINISTRATION. The administration of this Chapter was vested in the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade at the date of its preparation for inclusion. The present administration may be ascertained by reference to the most recent Determination of Titles and Responsibilities of Ministers made under Section 148(1) of the Constitution. TABLE OF CONTENTS. page. National Seas Act ………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Regulations …………………………………………………………………………………………….….– Subsidiary legislation ……………………………………………………………….…………………….11 Appendix- Source of Act. Prepared for inclusion as at 1/1/1980. 137 INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA. CHAPTER No. 361. National Seas Act. ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. PART I. PRELIMINARY. 1. Interpretation. "baseline" "low water elevation" "low water line" "miles". PART II. TERRITORIAL SEA. 2. Description of territorial sea. 3. Location of limits of territorial sea. 4. Baselines where no determination made. PART III. INTERNAL WATERS. 5. Description of internal waters. PART IV. OFFSHORE SEAS, 6. Description of offshore seas. PART V. ARCHIPELAGIC WATFRS. 7. Description of archipelagic waters. PART VI. MISCELLANEOUS. 8. Location of fines in cases of doubt. Prepared for inclusion as at 1/1/1980. 138 Ch. No. 361 National Seas PART VII. TRANSITIONAL. 9. Interim delimitation of archipelagic waters. SCHEDULES SCHEDULE 1.-Principles for Ascertaining Baselines. Sch. 1.1. –Interpretation of Schedule 1. Sch. 1.2. –General principle. Sch. 1.3. –Bays. Sch. 1.4. –Low water elevations. Sch. 1.5. –Rivers. SCHEDULE 2. –Interim Delimitation of Archipelagic Waters. INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA. CHAPTER No. 361. National Seas Act. Being an Act to describe and provide for the demarcation of— (a) the territorial sea; and (b) the internal waters; and (c) the offshore seas; and (d) the archipelagic waters, for the purpose of asserting the rights of the State in relation to those areas. -

International Airport Codes

Airport Code Airport Name City Code City Name Country Code Country Name AAA Anaa AAA Anaa PF French Polynesia AAB Arrabury QL AAB Arrabury QL AU Australia AAC El Arish AAC El Arish EG Egypt AAE Rabah Bitat AAE Annaba DZ Algeria AAG Arapoti PR AAG Arapoti PR BR Brazil AAH Merzbrueck AAH Aachen DE Germany AAI Arraias TO AAI Arraias TO BR Brazil AAJ Cayana Airstrip AAJ Awaradam SR Suriname AAK Aranuka AAK Aranuka KI Kiribati AAL Aalborg AAL Aalborg DK Denmark AAM Mala Mala AAM Mala Mala ZA South Africa AAN Al Ain AAN Al Ain AE United Arab Emirates AAO Anaco AAO Anaco VE Venezuela AAQ Vityazevo AAQ Anapa RU Russia AAR Aarhus AAR Aarhus DK Denmark AAS Apalapsili AAS Apalapsili ID Indonesia AAT Altay AAT Altay CN China AAU Asau AAU Asau WS Samoa AAV Allah Valley AAV Surallah PH Philippines AAX Araxa MG AAX Araxa MG BR Brazil AAY Al Ghaydah AAY Al Ghaydah YE Yemen AAZ Quetzaltenango AAZ Quetzaltenango GT Guatemala ABA Abakan ABA Abakan RU Russia ABB Asaba ABB Asaba NG Nigeria ABC Albacete ABC Albacete ES Spain ABD Abadan ABD Abadan IR Iran ABF Abaiang ABF Abaiang KI Kiribati ABG Abingdon Downs QL ABG Abingdon Downs QL AU Australia ABH Alpha QL ABH Alpha QL AU Australia ABJ Felix Houphouet-Boigny ABJ Abidjan CI Ivory Coast ABK Kebri Dehar ABK Kebri Dehar ET Ethiopia ABM Northern Peninsula ABM Bamaga QL AU Australia ABN Albina ABN Albina SR Suriname ABO Aboisso ABO Aboisso CI Ivory Coast ABP Atkamba ABP Atkamba PG Papua New Guinea ABS Abu Simbel ABS Abu Simbel EG Egypt ABT Al-Aqiq ABT Al Baha SA Saudi Arabia ABU Haliwen ABU Atambua ID Indonesia ABV Nnamdi Azikiwe Intl ABV Abuja NG Nigeria ABW Abau ABW Abau PG Papua New Guinea ABX Albury NS ABX Albury NS AU Australia ABZ Dyce ABZ Aberdeen GB United Kingdom ACA Juan N. -

This Keyword List Contains Pacific Ocean (Excluding Great Barrier Reef)

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 3/2/2016 Pacific Ocean (without the Great Barrier Reef) This keyword list contains Pacific Ocean (excluding Great Barrier Reef) place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Pacific Ocean (without Great Barrier Reef)” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Cauit Reefs (13N123E0016) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Legaspi (13N123E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Manito Reef (13N123E0015) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Matalibong ( Bariis ) (13N123E0006) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Rapu Rapu Island (13N124E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Albay Gulf > Sto. Domingo (13N123E0002) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amalau Bay (14S170E0012) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > Amami-Gunto > Amami-Gunto (28N129E0001) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > American Samoa (14S170W0000) OCEAN BASIN > Pacific Ocean > American Samoa > Manu'a Islands (14S170W0038) OCEAN BASIN > -

Eau-Map-Es-1

139°30'E 141°0'E 142°30'E 144°0'E 145°30'E Sorol Atoll Olimarau Atoll Lamotrek Atoll N Atoll N ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 7 7 Elato Atoll Woleai Atoll Ifalik Atoll Eauripik Atoll N N ' ' 0 0 ° ° 6 6 Federated States of Micronesia FSM-ECS-FP01 FSM-ECS-FP02 N N ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 4 4 E E A FSM-ECS-FP03 A FSM-ECS-FP64 FSM-ECS-FP63 U U West Caroline Basin R R East Caroline Basin FSM-ECS-FP62 I I FSM-ECS-FP04 N N ' ' 0 0 ° ° 3 3 P FSM-ECS-FP24 P II FSM-ECS-FP61!> FSM-ECS-FP25 FSM-ECS-FP38 KK FSM-ECS-FP58 R N II N ' ' 0 !> 0 3 3 ° ° 1 FSM-ECS-FP60 1 S E Papua New Guinea Indonesia ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 Sae Island Banehan Island Manu Island S Aua Island S ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 1 1 Wuvulu Island 139°30'E 141°0'E 142°30'E 144°0'E 145°30'E Location Diagram The outer limit of the continental shelf of Federated States of Micronesia in the Eauripik Rise region showing the provisions of article 76 invoked Pacific Ocean Eauripik Rise Scale 1:1,250,000 100 200 0 350 Nautical Miles 0 60 Explanitory notes: 1. This map was created using ESRI ArcGIS and Geocap AS GIS software with spatially correct data referenced to the World Geodetic System 1984 Spheroid, Semimajor Axis: 6378137.000000, Semiminor Axis: 6356752.3142452, Inverse Flattening: 298.257224 Article 76 fixed points (outer limit) FSM territorial sea baseline Gridded Bathymetry (m) 0 2. -

Alternativeislandnamesmel.Pdf

Current Name Historical Names Position Isl Group Notes Abgarris Abgarris Islands, Fead Islands, Nuguria Islands 3o10'S 155oE, Bismarck Arch. PNG Aion 4km S Woodlark, PNG Uninhabited, forest on sandbar, Raised reef - being eroded. Ajawi Geelvink Bay, Indonesia Akib Hermit Atoll having these four isles and 12 smaller ones. PNG Akiri Extreme NW near Shortlands Solomons Akiki W side of Shortlands, Solomons Alcester Alacaster, Nasikwabu, 6 km2 50 km SW Woodlark, Flat top cliffs on all sides, little forest elft 2005, PNG Alcmene 9km W of Isle of Pines, NC NC Alim Elizabeth Admiralty Group PNG Alu Faisi Shortland group Solomons Ambae Aoba, Omba, Oba, Named Leper's Island by Bougainville, 1496m high, Between Santo & Maewo, Nth Vanuatu, 15.4s 167.8e Vanuatu Amberpon Rumberpon Off E. coast of Vegelkop. Indonesia Amberpon Adj to Vogelkop. Indonesia Ambitle Largest of Feni (Anir) Group off E end of New Ireland, PNG 4 02 27s 153 37 28e Google & RD atlas of Aust. Ambrym Ambrim Nth Vanuatu Vanuatu Anabat Purol, Anobat, In San Miguel group,(Tilianu Group = Local name) W of Rambutyo & S of Manus in Admiralty Group PNG Anagusa Bentley Engineer Group, Milne Bay, 10 42 38.02S 151 14 40.19E, 1.45 km2 volcanic? C uplifted limestone, PNG Dumbacher et al 2010, Anchor Cay Eastern Group, Torres Strait, 09 22 s 144 07e Aus 1 ha, Sand Cay, Anchorites Kanit, Kaniet, PNG Anatom Sth Vanuatu Vanuatu Aneityum Aneiteum, Anatom Southernmost Large Isl of Vanuatu. Vanuatu Anesa Islet off E coast of Bougainville. PNG Aniwa Sth Vanuatu Vanuatu Anuda Anuta, Cherry Santa Cruz Solomons Anusugaru #3 Island, Anusagee, Off Bougainville adj to Arawa PNG Aore Nestled into the SE corner of Santo and separated from it by the Segond Canal, 11 x 9 km. -

National Seas Act (Chapter 361) INDEPENDENT STATE of PAPUA

National Seas Act (Chapter 361) INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA. CHAPTER No. 361. National Seas Act. Being an Act to describe and provide for the demarcation of— (a) the territorial sea; and (b) the internal waters; and (c) the offshore seas; and (d) the archipelagic waters, for the purpose of asserting the rights of the State in relation to those areas. PART I.—PRELIMINARY. 1. Interpretation. (1) In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears— "baseline" means territorial sea baseline; "low water elevation" means a naturally formed area of land surrounded by and above water at mean low water springs but submerged at high water; "low water line" means the low water line at mean low water springs; "miles" means international nautical miles. (2) For the purposes of this Act— (a) the eastern part of the island of New Guinea; and (b) each island under the sovereignty of the State, shall be deemed to have a separate continuous baseline. PART II.—TERRITORIAL SEA. 2. Description of territorial sea. The territorial sea of the State comprises all the waters, being waters forming part of the offshore seas, contained between the baselines and the outer-limit lines except for any such waters proclaimed under this section by the Head of State, acting on advice, not to form part of the territorial sea. 3. Location of limits of territorial sea. (1) In this section "limit point" means a point that is 12 miles seaward from the nearest point on a baseline. (2) For the purposes of Section 2— (a) the location of a baseline or a part of a baseline may be determined by the Head of State, acting on advice, by notice in the National Gazette; and (b) an outer-limit line is the line every point of which is a limit point.