The Social Context of Pinball: the Making of a Setting and Its Etiquette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World in an Amusement Arcade!

contents Founded in 2005 4th year Issue 28 March 2008 Editing AMUSEMENT TIME VIA A.CRISTIANO 4 80028 GRUMO NEVANO (NA) ITALY Editor in chief Dott.ENRICO D’ANIELLO Publisher PHANTASMATA GROUP Advertising, Marketing & Communication [email protected] Contact & News [email protected] Pag.4 Subscripton Sending a free request to [email protected] Amusement NEWS Subscribed Readers : 29.651 Supplement to registration N°59 del 30 Settembre 2005 del Tribunale di Napoli. From world All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission of the publisher is prohibited. Amusement Time © 2008 Pag.29 amusement events Amusement news from world Soundnet - Formerly Known As DT Productions DT Productions will from now on be known exclusively as Soundnet. Soundnet was previously the name used solely for the division of DT Productions that dealt with the digital jukebox industry. However, the name will now cover all the company's business supplying audio and audio/visual content to pubs, bars, shops and clubs. Soundnet sums up the business activity of the company and with a number of new audio, video and karaoke products set for release in 2008 it makes sense to standardise the business into only one brand for recognition purposes. Soundnet specialises in bespoke music and video compilations that capture a brand's unique personality. From mainstream pop to hardcore rock, every programme is carefully compiled from the exclusive library of 50,000 audio titles, 30,000 video titles and 5,000 karaoke tracks. The programming department sources all the content directly from the record labels at the same time as it is dispatched to radio and TV. -

ABSTRACT This Paper Offers a Social History of Funfairs and Arcades In

ABSTRACT This paper offers a social history of funfairs and arcades in mid-20th century urban England. Critiquing existing histories of games for often neglecting players and the specific locales in which games are played, it draws on both new cinema history and cultural studies’ conception of ‘radical contextualism’ to outline what the paper describes as a game’s ludosity. Ludosity, the paper proposes, condition or quality of game experience as shaped by a range of agents, institutions and contexts. Utilising mass observation records, it offers a detailed analysis of the ways in which social interactions influenced ludic experiences of pinball tables and crane machines and posits that games history needs to centre players in order to fully conceptualize games in history. KEYWORDS Games history; social history; arcades; pinball; cultural studies. INTRODUCTION Fun fairs and amusement arcades mushroomed in England’s cities during the 1930s and 40s, to the extent that The Guardian described a ‘fun fair craze’ (‘The Fun Fair Craze’, 1938, p.8). The Daily Mail, the mouthpiece of middle-England, breathlessly portrayed the sights and sounds of these new spaces: Click, click, click! The ball runs down the table, bounces against springs, falls into a slot, is shot back again. Bells ring. Lights appears. On a picturesque background figures dance to the evolutions of a rising score . A crowd gathers round, for the games as fascinating to watch as to play. (Crofton, 1939, p.10) In blending the mechanical and electrical systems with the social experiences specific to the English urban milieus, this description hints at the overarching and interconnected arguments 1 presented in this paper. -

Bird's Eye View

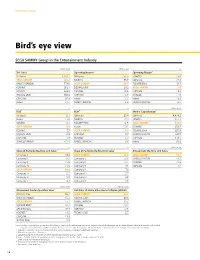

DETERMINATION Bird’s eye view SEGA SAMMY Group in the Entertainment Industry Billions of yen Billions of yen % Net Sales 1 Operating Income 1 Operating Margin 1 Nintendo 1,434.3 Nintendo 356.5 SANKYO 25.0 SEGA SAMMY 384.6 SANKYO 55.7 Nintendo 24.9 NAMCO BANDAI 378.5 SEGA SAMMY 36.7 SQUARE ENIX 14.7 KONAMI 262.1 SQUARE ENIX 28.2 SEGA SAMMY 9.5 SANKYO 222.6 KONAMI 18.6 CAPCOM 8.4 SQUARE ENIX 192.2 CAPCOM 5.5 KONAMI 7.1 CAPCOM 66.8 Heiwa 3.7 Heiwa 5.9 Heiwa 63.3 NAMCO BANDAI 1.8 NAMCO BANDAI 0.5 % % Billions of yen ROE 1 ROA 1, 2 Market Capitalization 4 Nintendo 17.7 Nintendo 20.4 Nintendo 4,434.2 Heiwa 13.0 SANKYO 12.4 SANKYO 451.3 SANKYO 9.1 SQUARE ENIX 11.5 SEGA SAMMY 320.6 SEGA SAMMY 8.8 Heiwa 9.1 KONAMI 258.7 KONAMI 7.3 SEGA SAMMY 8.5 SQUARE ENIX 235.8 SQUARE ENIX 6.3 CAPCOM 5.7 NAMCO BANDAI 227.7 CAPCOM 3.8 KONAMI 3 5.7 CAPCOM 119.5 NAMCO BANDAI –12.4 NAMCO BANDAI 0.6 Heiwa 95.9 % % Billions of yen Share of Pachinko Machine Unit Sales 5 Share of Pachislot Machine Unit Sales 5 Amusement Machine Unit Sales 1 Company S 18.0 SEGA SAMMY 21.3 SEGA SAMMY 45.1 Company S 17.2 Company S 13.6 NAMCO BANDAI 44.0 Company K 12.8 Company U 13.1 KONAMI 32.8 Company N 11.9 Company Y 9.5 CAPCOM 2.2 SEGA SAMMY 10.8 Company K 7.8 Company H 5.1 Company H 5.7 Company D 5.0 Company D 4.6 Company F 4.7 Company A 3.9 Billions of yen Millions of units Amusement Center Operation Sales 1 Unit Sales of Home Video Game Software (Global) ROUND ONE 82.1 SEGA SAMMY 26.7 NAMCO BANDAI 65.3 SQUARE ENIX 26.6 SEGA SAMMY 54.7 NAMCO BANDAI 22.7 SQUARE ENIX 6 52.2 KONAMI 20.2 AEON Fantasy 43.7 CAPCOM 12.5 ADORES 7 19.5 TECMO KOEI 5.7 CAPCOM 11.9 TECMO KOEI 3.3 Note: The above is intended to give an idea of the Group’s position in the industry and only covers companies for which information can be obtained from published documents, such as listed companies or over-the-counter (OTC) companies. -

History of Video Games-Wikipedia

History of video games From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Atari VCS was a popular home video game console in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Pictured is the four-switch model from 1980–1982. An Atari CX40 joystick controller, with a single button The history of video games goes as far back as the early 1950s, when academic computer scientists began designing simple games and simulations as part of their research or just for fun. At M.I.T. in the 1960s, professors and students played games such as 3D tic-tac-toe and Moon Landing. These games were played on computer such as the IBM 1560, and moves were made by means of punch cards. Video gaming did not reach mainstream popularity until the 1970s and 1980s, when video arcade games and gaming consoles using joysticks, buttons, and other controllers, along with graphics on computer screens and home computer games were introduced to the general public. Since the 1980s, video gaming has become a popular form of entertainment and a part of modern popular culture in most parts of the world. One of the early games was Spacewar!, which was developed by computer scientists. Early arcade video games developed from 1972 to 1978. During the 1970s, the first generation of home consoles emerged, including the popular game Pong and various "clones". The 1970s was also the era of mainframe computer games. The golden age of arcade video games was from 1978 to 1982. Video arcades with large, graphics- decorated coin-operated machines were common at malls and popular, affordable home consoles such as the Atari 2600 and Intellivision enabled people to play games on their home TVs. -

Designing Facility Layout Using Business Intelligence Approach: a Case Study in an Amusement Arcade

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Sao Paulo, Brazil, April 5 - 8, 2021 Designing Facility Layout Using Business Intelligence Approach: A Case Study in an Amusement Arcade Tanti Octavia, Siana Halim and Christian Alianto Industrial Engineering Department Petra Christian University Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper discus a facility layout design in an amusement arcade in Surabaya. In this arcade, there are many idle game machines, since the customers only play in certain games. This problem is difficult to resolve since playing patterns and game categories have not been acknowledged. Business intelligence are used to analyze play patterns so that the game machines layout could be proposed. The proposed layout of game machines also applies the concept of store’s layout. The purpose of this study is to propose game machine layout considering the playing patterns and categories. The results of this study are to develop a new layout design with considering age. The new layout design is to juxtapose the game machine which has the biggest revenue in a category with game machine which has the smallest revenue from other categories. These juxtapositions do not cost any money because they are done during working hours and using manpower. The proposed layout attracts customers spend their money to play. Keywords Business Intelligence, Data Mining, Facility Layout, Power BI 1. Introduction Traditionally, the main objective of facility layout problem is to minimize the total material flow cost. Facilities layout design refers to the arrangement of all equipment, machinery and furnishings within a building envelope after considering various objectives of the facility (Riedel 2011). -

NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc

NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. Annual Report NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. 2010 www.bandainamco.co.jp/ Annual Report 2010 NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. Printed in Japan Profile The BANDAI NAMCO Group develops entertainment-related products and services in a wide range of fields, including toys, game software, arcade game machines, visual content, music content, and amuse- ment facilities. We aim to become a “Globally Recognized Entertainment Group” by establishing a strong operational foundation in Japan while aggressively developing operations in overseas markets to secure future growth. Our Mission Statement Dreams, Fun and Inspiration “Dreams, Fun and Inspiration” are the Engine of Happiness. Through our entertainment products and services, BANDAI NAMCO will continue to provide “Dreams, Fun and Inspiration” to people around the world, based on our boundless creativity and enthusiasm. Our Vision The Leading Innovator in Global Entertainment As an entertainment leader across the ages, BANDAI NAMCO is constantly exploring new areas and heights in entertainment. We aim to be loved by people who have fun and will earn their trust as the “Leading Innovator in Global Entertainment.” RESTART In April 2010, the BANDAI NAMCO Group launched the Restart Plan to counter the lengthening economic slump and the Group’s declining performance. Under the Restart Plan, the Group will work to bolster its operational foundation to support the implementation of the current Mid-term Business Plan. Goals of the Restart Plan • Transforming into a speedy group • Improving -

NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. Printed in Japan Annual Report 2009 AC Adiholdings Inc

NAMCO BANDAINAMCO Inc. Holdings Aiming to be a “Globally Recognized Annual Report 2009 Entertainment Group” Globally Recognized The BANDAI NAMCO Group develops entertainment-related products and services in a wide range of fields, including toys, video game software, arcade game machines, visual and music products, and amusement facilities. We aim to be a “Globally Recognized Entertainment Group” by establishing a strong operational Entertainment foundation in the domestic market, while aggressively developing operations in overseas markets to secure future growth. Moving forward, the BANDAI NAMCO Group will continue to provide “Dreams, Fun and Inspiration” to people around the Group world through entertainment based on creativity and boundless enthusiasm. NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. www.bandainamco.co.jp Printed in Japan Annual Report 2009 NAMCO BANDAINAMCO Inc. Holdings Aiming to be a “Globally Recognized Annual Report 2009 Entertainment Group” Globally Recognized The BANDAI NAMCO Group develops entertainment-related products and services in a wide range of fields, including toys, video game software, arcade game machines, visual and music products, and amusement facilities. We aim to be a “Globally Recognized Entertainment Group” by establishing a strong operational Entertainment foundation in the domestic market, while aggressively developing operations in overseas markets to secure future growth. Moving forward, the BANDAI NAMCO Group will continue to provide “Dreams, Fun and Inspiration” to people around the Group world through entertainment based on creativity and boundless enthusiasm. NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. www.bandainamco.co.jp Printed in Japan Annual Report 2009 Our Mission Statement Our Vision Corporate Data 70 71 As of March 31,2009 NAMCO BANDAI Holdings Inc. -

The Sandown Amusement Arcades

THE SANDOWN AMUSEMENT ARCADES By Dave Bambrough 2013 (part one) The idea for an “Amusement Park” in Culver Road was initiated by one Mrs Gertrude Emma Taylor, married for 45 years with 10 children (this may have been exaggeration to suit the moment, as only two of her off spring attended her funeral) and a resident of Shanklin. A late challenge for someone not exactly in their prime of life, without doubt a lady of visionary qualities. A property owner in Surrey before moving to the Island, she also owned East Cliff Social Club, a Café in Shanklin and lived in a large house named La Turbie, Culver Road, Shanklin. Previous to Amusement Arcades an early form of light amusement for holidaymakers came by way of a game named “Bubbles”. Site competition for this was by way of tenders to the local Council as portrayed in the November 1924 caption. The game, a simple one, with several competing players were required to catch 3 ping pong type balls in a net on the end of a long stick, the first player to do so won a prize. The proposed first amusement site in Sandown had formerly been home to Sandown Coastguard Boathouse. (Kelly’s 1924/5 Isle of Wight directories listed it as “in operation” with Joseph Butterfield the Chief Officer in charge). The Coast Guard Station stood on land later occupied by “Dragonetti’s” hot dog stall, (for those that remember) adjacent to this stood the seven Coast Guard cottages, which were in turn adjacent to the Boathouse, which occupied the land the Amusement Park was to be built on. -

Twilight of the Seaside Amusement Arcade

Twilight of the seaside amusement arcade Amusement arcades have been largely overlooked within the broader literature on tourism and leisure pursuits and attractions. Furthermore the contribution of the amusement arcade to the character and experience of British seaside resorts has not been considered. The amusement arcade industry is currently divided into a number of distinctive sectors, of which the family oriented arcades found at Britain's coastal resorts are one. Amusement arcades are generally considered to be a traditional and quintessential part of British seaside resorts. However, the seaside arcades are facing challenging times putting the amusements, and the buildings in which they are housed, increasingly at risk. Amusement arcades originally developed from travelling fairs, with the first British examples appearing in the early 19th century in the form of games stalls and shows. The first automated machine of any kind is considered to be a stamp vendor patented in 1857 and by the end of the 19th century there was evidence of automated entertainment machines in the UK. During this period many former travelling showman decided to settle in seaside resorts and establish ‘sports’ arcades or ‘gaff shops’ and it is in this context that automated machines started to appear in funfairs and on piers along the British coast. These early machines included automated fortune-tellers, shooting ranges, strength-testers and kinematographs. During the early 20th century formal arcades featuring a collection of permanent automated machines such as mutoscopes, automated football, punchballs and mechanical clowns appeared in many resorts. They were usually situated along a resort’s promenade, with the first purpose-built amusement arcade generally considered to be Barron’s ‘Paradium’, located on Marine Parade in Great Yarmouth, which was opened in 1902. -

Hands on Media History;A New Methodology in the Humanities And

9 EXTENDED PLAY Hands on with 40 years of English amusement arcades Alex Wade Amusement arcades are historically viewed as an unflattering venue where devi ancy and dereliction run as free as the youth who populate them (see e.g. Fisher 1995; Huff and Collinson 1987). Popular books of the time reflect this, from the tongue-in-cheek narrative interpretation of Rubin’s Defending the Galaxy (1982), to Amis’s graphic – both visually and linguistically – Invasion of the Space Invad ers (1982), to Sudnow’s cold-war bad-trip of Breakout addiction Pilgrim in the Microworld (1983). Each documents and reinforces the popular notion of arcades as arenas where, as distinguished game designer Al Alcorn observes, “naughty things might happen” (Alcorn 2014, 25). The end result was a moral panic, which found its political manifestation in George Foulkes’ infamous campaign to limit “the menace of video games” (Haddon 1988, 60), via the United King dom parliament in the Control of Space Invaders (and other electronic games) Bill (Foulkes 1981, cc287). This popular and political attention piqued the interest of sociologists, psychologists, and criminologists. The videogame amusement arcade became a favoured and fevered site of academic study, which, to the delight of writers and the panic of politicians and parents reinforced the notion that arcades were a locus of dubious, unethical, and perhaps even illegal behaviour. A large- scale study by the Centre for Leisure Research in the UK found that 80% of 2739 respondents disagreed that amusement arcades provided young people with a safe place to go, while 59% of the same cohort agreed that young people should be banned from amusement arcades (Centre for Leisure Research 1990). -

Sacona India: US Domestic Market Entry Strategy

Jered Gaspard Clara Villain Pauline Singh Suresh Banothu X-culture Project Sacona India: US Domestic Market Entry Strategy 11/17/2016 Executive Summary Sacona India, a competitor in the Indian arcade amusements industry, began operating in 2007 with offerings including a unique lineup of video game machines based on home video game consoles and several physical sports-based games in which the user’s body is part of the action. Since 2012, Sacona has renewed its focus on these physical sports games, and is seeking entry into new markets to build the brand into an international name. The firm sets itself apart from competitors through the self-developed high-quality mechatronics technology in its sports gaming products. By engineering the units around easily-accessible standard parts, overall service costs are decreased, reducing the products’ total cost of ownership. In this analysis we have given an overview of the arcade amusements industry from the standpoint of today’s major players, and used their market research data to identify viable markets for Sacona’s entry. After selecting the United States domestic market as the most potentially profitable market, we have given an overview of the general US economic situation, the arcade industry in the US, and its legal and regulatory environments. We have recommended what we believe is the optimal mode of market entry--direct export--and identified a number of potential distributors in the US market that can help to get Sacona’s products in front of consumers. After presenting a breakdown of logistics and trade regulations applicable to international commerce between India and the US, we have used the available pricing and regulatory information to recommend a specific product on which to focus--Dodge Ball--and a recommended pricing structure. -

Intellectual Properties Current Assets Securities and Goodwill

the GROUP Management Resources Creating Entertainment Value Entertainment companies recognize intel- Assets lectual properties obtained through the Total investments and acquisition of companies in investment other assets Intellectual Properties Current assets securities and goodwill. However, they do Intellectual properties obtained through acqui- not recognize intellectual properties they Noncurrent assets The SEGA SAMMY Group boasts diverse intellectual properties, which such operating companies as sitions recognized as Current assets have created in-house or licensed as assets. intellectual properties SEGA and Sammy have created during their long histories. These intellectual properties have transcended Noncurrent assets Therefore, if such intangible assets were created in-house; licensed Asset value not shown generations and earned strong endorsement worldwide. We have ensured our intellectual properties taken into account, asset values would be intellectual properties in balance sheets create long-term entertainment value through multifaceted rollouts catering to current needs. higher than fi nancial statements show. not recognized Intellectual Property Creation, Acquisition, and Development the PAST the PRESENT We build our intellectual property portfolio based on a fl exible approach that incorporates intellectual properties created in-house, intellectual properties obtained through mergers and acquisitions (M&As), and major intellectual properties licensed from third parties. At the same time, we advance multifaceted rollouts of intellectual properties to increase points of contact with users and the value of intellectual properties continuously. Sonic Lost World ©SEGA Packaged game software Multifaceted rollout Sonic Arcade Sonic Dash ©SEGA ©SEGA ©SEGA Networks Intellectual First Pachislot and Packaged game Amusement Total Cumulative unit sales / Amusement arcade Digital game Toys machines Digital games property title appearance pachinko machines software arcade machines editions downloads Sonic the Hedgehog 1991 — Approx.