4 Overview of the Fraser River War (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

Green Tech Exchange Forum

Green Tech Exchange Forum May 25, 2016 SFU Harbor Centre Presentation Chief Patrick Michell Kanaka Bar Indian Band “What we do to the lands, we do to ourselves.” The Indigenous People of Canada All diverse with distinct languages, culture and history. Canada • Celebrating 150 Years on July 1 2017 • 630 Bands • Metis and Inuit too British Columbia • Joined Canada in 1871 • 203 Bands The Nlaka’pamux Nation Archeology indicates an indigenous population living on the land for 7,000 years +. 1808: First Contact with French NWC with arrival of Simon Fraser. • First named Couteau Tribe. • Later renamed the Thompson Indian. 1857-58: Fought Americans to standstill in the Fraser Canyon War 1876: 69 villages amalgamated into 15 Indian Bands under the Indian Act 1878: Reserve Land allocations Kanaka Bar Indian Band • One of the original Nlaka’pamux communities. • Webpage: www.kanakabarband.ca • 66 members on reserve, 150 off • Codified: Election, Membership and Governance Codes in 2013. • Leadership: an indefinite term but face recall every 3rd Thursday. Land Use Plan (March 2015). Community Economic Development Plan (March 2016). Bi-annual implementation plans. Holistic: what one does affects another Kanaka Bar Indian Band Organization Chart As at May 2, 2016 Kanaka Bar & British Columbia Clean Energy Sectors Large Hydro Geothermal Tidal Wave N/A Applicable some day? N/A N/A Biomass Solar Run of River Wind Considered: not yet? 1.5 Projects 1.5 Projects Concept Stage How are we doing this? BC Hydro (the buyer of electrons) Self-sufficiency (off grid) Net Metering: projects under 100Kw Generating electrons for office, can connect to grid. -

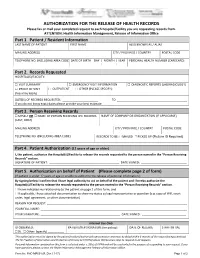

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

To Read an Excerpt from Claiming the Land

CONTENTS S List of Illustrations / ix Preface / xi INTRODUCTION Fraser River Fever on the Pacific Slope of North America / 1 CHAPTER 1 Prophetic Patterns: The Search for a New El Dorado / 13 CHAPTER 2 The Fur Trade World / 36 CHAPTER 3 The Californian World / 62 CHAPTER 4 The British World / 107 CHAPTER 5 Fortunes Foretold: The Fraser River War / 144 CHAPTER 6 Mapping the New El Dorado / 187 CHAPTER 7 Inventing Canada from West to East / 213 CONCLUSION “The River Bears South” / 238 Acknowledgements / 247 Appendices / 249 Notes / 267 Bibliography / 351 About the Author / 393 Index / 395 PREFACE S As a fifth-generation British Columbian, I have always been fascinated by the stories of my ancestors who chased “the golden butterfly” to California in 1849. Then in 1858 — with news of rich gold discoveries on the Fraser River — they scrambled to be among the first arrivals in British Columbia, the New El Dorado of the north. To our family this was “British California,” part of a natural north-south world found west of the Rocky Mountains, with Vancouver Island the Gibraltar-like fortress of the North Pacific. Today, the descendants of our gold rush ancestors can be found throughout this larger Pacific Slope region of which this history is such a part. My early curiosity was significantly moved by these family tales of adventure, my great-great-great Uncle William having acted as fore- man on many of the well-known roadways of the colonial period: the Dewdney and Big Bend gold rush trails, and the most arduous section of the Cariboo Wagon Road that traversed and tunnelled through the infamous Black Canyon (confronted by Simon Fraser just a little over 50 years earlier). -

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon Brian Pegg* Introduction ritish Columbia was created as a political entity because of the events of 1858, when the entry of large numbers of prospectors during the Fraser River gold rush led to a short but vicious war Bwith the Nlaka’pamux inhabitants of the Fraser Canyon. Due to this large influx of outsiders, most of whom were American, the British Parliament acted to establish the mainland colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858.1 The cultural landscape of the Fraser Canyon underwent extremely significant changes between 1858 and the end of the nineteenth century. Construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the Canadian Pacific Railway, the establishment of non-Indigenous communities at Boston Bar and North Bend, and the creation of the reserve system took place in the Fraser Canyon where, prior to 1858, Nlaka’pamux people held largely undisputed military, economic, legal, and political power. Before 1858, the most significant relationship Nlaka’pamux people had with outsiders was with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which had forts at Kamloops, Langley, Hope, and Yale.2 Figure 1 shows critical locations for the events of 1858 and immediately afterwards. In 1858, most of the miners were American, with many having a military or paramilitary background, and they quickly entered into hostilities with the Nlaka’pamux. The Fraser Canyon War initially conformed to the pattern of many other “Indian Wars” within the expanding United States (including those in California, from whence many of the Fraser Canyon miners hailed), with miners approaching Indigenous inhabitants * The many individuals who have contributed to this work are too numerous to list. -

Farrell & Waatainen, 2020 Canadian Social Studies, Volume 51

Farrell & Waatainen, 2020 Canadian Social Studies, Volume 51, Issue No. 2 Face-to-Face with Place: Place-Based Education in the Fraser Canyon Teresa Farrell Instructor, Faculty of Education Vancouver Island University [email protected] Paula Waatainen Instructor, Faculty of Education Vancouver Island University [email protected] This work was supported by funding received from a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Exchange Grant, a Vancouver Island University Innovate Grant, and funds from the Faculty of Education, Vancouver Island University. Two instructors from the Faculty of Education at Vancouver Island University organized a three-day field experience with 35 pre-service teachers along the Fraser Canyon corridor, home of the Nlaka’pamux and Stó:lō Nations. We asked: How will an educational field experience in this place impact and inform pre-service teachers and researchers’ understanding of place- based education (PBE) in their practice? We explore the shift towards Indigenous perspectives that subtly wove its way through the work and how it framed new ways of thinking about place for our participants and new ways of considering decolonizing education for the instructor researchers. We conclude by arguing that PBE is necessitated by active, living relationship in place and provides opportunities for critical pedagogy grounded in Indigeneity. We also suggest that both Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators have a role to play in this work. “Is it not time to face place – to confront it, take off its veil and see its full face.” (Johnson and Murton, 2007, p. 127). On September 12, 2019, two instructor researchers traveled with 35 pre-service teachers to a place that lived in our minds and hearts: the Fraser Canyon corridor1, in what is now British Columbia, Canada. -

Lillooet-Lytton Tourism Diversification Project

LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT by Ric Careless, Executive Director Wilderness Tourism Association for the Fraser Basin Council with funding from the Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management February 2005 LILLOOET-LYTTON TOURISM PROJECT 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ..................................................................................4 1.1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Terms of Reference............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Study Area Description...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Local Economic Challenges............................................................................................................................... 8 2. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF TOURISM.....................................................................9 2.1 Tourism in British Columbia............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Nature-Based Tourism and Rural BC............................................................................................................ -

Download Download

Ames, Kenneth M. and Herbert D.G. Maschner 1999 Peoples of BIBLIOGRAPHY the Northwest Coast: Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson, London. Abbas, Rizwaan 2014 Monitoring of Bell-hole Tests at Amoss, Pamela T. 1993 Hair of the Dog: Unravelling Pre-contact Archaeological Site DhRs-1 (Marpole Midden), Vancouver, BC. Coast Salish Social Stratification. In American Indian Linguistics Report on file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. and Ethnography in Honor of Lawrence C. Thompson, edited by Acheson, Steven 2009 Marpole Archaeological Site (DhRs-1) Anthony Mattina and Timothy Montler, pp. 3-35. University of Management Plan—A Proposal. Report on file, British Columbia Montana Occasional Papers No. 10, Missoula. Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Andrefsky, William, Jr. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1976 Gulf of Georgia Archaeological Analysis (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, New York. Survey: Powell River and Sechelt Regional Districts. Report on Angelbeck, Bill 2015 Survey and Excavation of Kwoiek Creek, file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. British Columbia. Report in preparation by Arrowstone Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1977 An Archaeological Resource Archaeology for Kanaka Bar Indian Band, and Innergex Inventory of the Northeast Gulf of Georgia Region. Report on file, Renewable Energy, Longueuil, Québec. British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Angelbeck, Bill and Colin Grier 2012 Anarchism and the Adachi, Ken 1976 The Enemy That Never Was. McClelland & Archaeology of Anarchic Societies: Resistance to Centralization in Stewart, Toronto, Ontario. the Coast Salish Region of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Current Anthropology 53(5):547-587. Adams, Amanda 2003 Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, B.C. -

The Cariboo Wagon Road

THE CARIBOO WAGON ROAD he success of the Cariboo goldfields necessitated the further Timprovement of the roads to the Cariboo. In May 1862, Colonel Richard C. Moody advised Governor James Douglas that the Yale to Cariboo route through the Fraser Canyon was the best to adapt for the general development of the country and that it was imperative its construction start at once. The governor concurred and it was decided that the road would be a full 18-feet wide in order to accommodate wagons going and coming from the goldfields and thus it came to be known as the Cariboo Wagon Road. The builders were to be paid large cash subsidies as work progressed and upon completion of their sections were to be granted permission to collect tolls from the travelers for the following 5 years. Captain John Marshall Grant of the Royal Engineers, with a force of sappers, miners, and civilian labor, was to construct the first six miles out of Yale, while Thomas Spence was to extend the road the next seven miles to Chapman’s Bar, at a cost of $47,000. From here, Joseph William Trutch, Spence’s partner, was to tackle the section to a point that would become Boston Bar, a distance of 12 miles, at a cost of $75,000. From here, Spence would continue the road to Lytton. Walter Moberly, a successful engineer, with Charles Oppenheimer, a partner in the great mercantile firm ROYAL ENGINEER'S BUCKLE & BUTTONS. COURTESY WERNER KASCHEL of Oppenheimer Brothers, and Thomas B. Lewis accepted the challenge to build the section from Lytton until the road joined a junction with the wagon road to be built by Gustavus Blin Wright and John Colin Calbreath from Lillooet to Watson’s stopping house. -

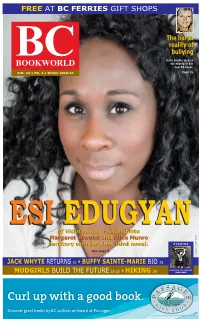

Esi Edugyan's

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS TheThe harshharsh realityreality ofof BC bullying bullying Holly Dobbie tackles BOOKWORLD the misery in her new YA novel. VOL. 32 • NO. 4 • Winter 2018-19 PAGE 35 ESIESI EDUGYANEDUGYAN ofof VictoriaVictoria hashas rocketedrocketed intointo MargaretMargaret AtwoodAtwood andand AliceAlice MunroMunro PHOTO territoryterritory withwith justjust herher thirdthird novel.novel. STAMINA POPPITT See page 9 TAMARA JACK WHYTE RETURNS 10 • BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE BIO 25 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT BUILD THE FUTURE 22-23 • 26 MUDGIRLS HIKING #40010086 Curl up with a good book. Discover great books by BC authors on board at Passages. Orca Book Publishers strives to produce books that illuminate the experiences of all people. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. We aim to help young readers see themselves refl ected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and the authors that we work with. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world. The World Around Us series 9781459820913 • $19.95 HC 9781459816176 • $19.95 HC 9781459820944 • $19.95 HC 9781459817845 • $19.95 HC “ambitious and heartfelt.” —kirkus reviews The World Around Us Series.com The World Around Us 2 BC BOOKWORLD WINTER 2018-2019 AROUNDBC TOPSELLERS* BCHelen Wilkes The Aging of Aquarius: Igniting Passion and Purpose as an Elder (New Society $17.99) Christine Stewart Treaty 6 Deixis (Talonbooks $18.95) Joshua -

Chinese Settlement in Canada

1 Chinese Settlement in Canada 1788-89: The first recorded Asians to arrive in Canada were from Macau and Guangdong province in Southern China. They were sailors, smiths, and carpenters brought to Vancouver Island by the British Captain John Meares to work as shipwrights. Meares transported 50 Chinese workers in 1788 and 70 more in 1789, but shortly thereafter his entire Chinese crew was captured and imprisoned when the Spanish seized Nootka Sound. What happened to them is a mystery. There are reports John Meares, the British captain who that some were taken as forced labourers to Mexico, that brought the first known Chinese to some escaped, and that some were captured by the Canada Nootka people and married into their community. The Fraser Canyon Gold Rush In 1856, gold was found near the Fraser River in the territory of the Nlaka’pamux First Nations people. Almost immediately, the discovery brought tens of thousands of gold miners to the region, many of them prospectors from California. This event marked the beginnings of white settlement on British Columbia’s mainland. Chinese man washing gold in the Fraser River (1875) Credit: Library and Archives Canada / PA-125990 By 1858, Chinese gold miners had also started to arrive. Initially they too came from San Francisco, but ships carrying Chinese from Hong Kong soon followed. By the 1860s, there were 6000-7000 Chinese people living in B.C. The Gold Rush brought not only Chinese miners to Western Canada, but also the merchants, labourers, domestics, gardeners, cooks, launderers, and other service industry workers needed to support the large mining communities that sprang up wherever gold was discovered.