Introspection in Shakespeare's Coriolanus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2015

Jan 15 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 161st birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 7 to Jan. 11. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at Annie Moore's, and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morn- ing, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was Alan Bradley, co-author of MS. HOLMES OF BAKER STREET (2004), and author of the award-winning "Flavia de Luce" series; the title of his talk was "Ha! The Stars Are Out and the Wind Has Fallen" (his paper will be published in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal). The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's Restaurant was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton and An- drew Joffe) entertained the audience with an updated version of "The Sher- lock Holmes Cable Network" (2000). The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber), which honors the most whimsical piece in The Ser- pentine Muse last year: the winner (Jenn Eaker) received a certificate and a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's traditional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportunities to browse and buy. -

A Midsummer Nights Dream 11 'T} S , O(;;)-2 by Wilham Shakespeare

A Midsummer NightS Dream 11 't} s , o(;;)-2 by WilHam Shakespeare ~ BAm~ Tiieater BRooKLYN AcADEMY oF Music Compa11y ~~~~~~~~~ \.. ~ , •' II I II Q ,\.~ I II 1 \ } ( "' '" \ . • • !I II'" r )DO I \ ., : \ I ~\ } .. \ ;; .; 'I' ... .. _:..,... 1t ; rJ ,.I •\ y v \ YOUR MONEY GROWS LIKE MAGIC AT THE THE DIME SAVINGS BANK DF NEW YORK -..1-..ett•O•C MANHATTAN • DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN • BENSONHURST • FLATBUSH CONEY ISLAND • KINGS PLAZA • VALLEY STREAM • MASSAPEQUA HUNTINGTON STATION TABLE OF Old CONTENTS Hungary "An authentic ~ ounpany~~~~~~~ Hungarian restaurant right here in Brooklyn" Beef Goulash, Ch1cken Papnka, St uffed Cabbage, Palacsinta and other traditional dishes " Live Piano Music Nightly" The Actors 5-8 PRE-T HEATRE AND AFTER THEATRE DINNER 142 Montague St., Bklyn . Hghts. Notes on the Play 9-14 625· 1649 Production Team 15 § The Staff 16 'R(!tauranb The Actors 17-19 tel: 855-4830 Contributors 20-21 UL8-2000 Board of Directors 22 open daily for lunch and dinner till 9 P. M. Italian and A m erican Cuisine special orders upon request Flowers, plants and fruit baskets for all occasions (212) 768-6770 25th Street & 768-0800 5th Avenue Deluxe coach service following DIRECTORY BAM Theater Company Directory of Facilities a nd Services Box Office: Monday 10 00 to &.00 Tue.day throu~h ~tur performances day 10 00 to Y 00 Sunday Performance limes only Lost ond ~o und : Telephone &36-4 150 Restroom: Operu We pick you up and take you back llouse Women .ond Men. Mezzanme level. HandKapp<.·d Or c h c~t r a level Ployh ou,e: Women Orchestra l~vcl ,\.1cn .'Ae1 (to Manhattan) 1.anme lt•vel llandocapped Orchestra level Lepercq Spucc: The BAMBus Express will pick-up BAM Theater Company Wom en ,,nd Men Tht•c.H e r level Public T ele phon es. -

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: • Howard-Field Casting, (Los Angeles, London & Europe) 1993-2014 • Director of Feature Casting, Warner Bros. Studios, Los Angeles 1989-1993 • Howard-Field Casting ( London & Europe) 1983-1989 • Casting & Project Consultant RKO, London operations 1983-1985 • Associate Casting Director Royal Shakespeare Company, London 1977-1983 • Production Assistant to director/producer Martin Campbell, London 1975-1977 • Assistant to writer, Tudor Gates, Drumbeat Productions, London 1975-1977 FILMS CURRENTLY IN DEVELOPMENT FOR 2014/15: AMOK – Director: Kasia Adamik. Screenplay: Richard Karpala. Executive producer: Agnieszka Holland. Producers: Beata Pisula, Debbie Stasson - in development for spring 2015 WALKING TO PARIS – Director: Peter Greenaway, Producer: Kees Kasander and Julia Ton. Scheduled to commence pp February 2015 in Romania, Switzerland and France. THE WORLD AT NIGHT – Director: TBC. Screenplay: William Nicholson. Producer: Vanessa van Zuylen, (VVZ Presse, Paris, France), Matthias Ehrenberg, Jose Levy, (Cuatro Films Plus) Ibon Cormenzana, (Arcadia Motion Pictures), – in development to shoot Argentina and France Spring 2015. Daniel Bruhl attached. RACE – In association with Suzanne Smith Casting. Director: Stephen Hopkins. Filming Berlin and Canada, September 2014. Casting a selection of cameo roles from the UK AMERICAN MASSACRE – Director: TBC Producer: Emjay Rechsteiner (Staccato Films); Executive Producer: Harris Tulchin - in development for Spring 2015, shooting New Zealand and Canary Islands LITTLE SECRET (Pequeno Segredo) – Director: David Schurmann; Writer: Marcos Bernstein; Producers: Matthias Ehrenberg (Cuatro Films Plus), Joao, Roni (Ocean Films, Brazil), Emma Slade (Fire Fly Films, NZ), Barrie Osborn – in development to shoot Brazil, October 2014. Finnoula Flanagan attached THE BAY OF SILENCE: - Director: Mark Pellington; Screenwriter & Producer: Caroline Goodall, Executive Producer: Peter Garde. -

Alan Howard, MA, Phd, FRIC (1929–2020): As I Knew Him

International Journal of Obesity (2020) 44:2343–2346 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-00683-4 OBITUARY In Memoriam: Alan Howard, MA, PhD, FRIC (1929–2020): as I knew him George A. Bray1 Received: 14 August 2020 / Revised: 19 August 2020 / Accepted: 3 September 2020 / Published online: 9 October 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. This article is published with open access Howard, who worked in a mill, and Elsie (née Atkins), who was a tailor. After his father lost a finger in an accident at the mill, he used the compensation money to build up a tailoring business with his wife. After World War II they opened the Victory Café in Norwich. Alan was educated at City of Norwich grammar school where he played chess for the Norfolk and Norwich Club. At age 17, in 1946, he won the newly created Junior Championship Cup. He was also a 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: keen photographer with his own darkroom. Howard won a place at Downing College in Cambridge, England in 1948 where he studied Natural Sciences. He was elected to the Arthur Paul Saint Scholarship at Downing College in July 1952, a scholarship he held for 2 years. Dr. Howard’s PhD was approved on 30 Nov 1954 for research on ‘the reaction of diazonium compounds with amino acids and proteins and its application to serological problems’.He received both his MA and PhD on 22 Jan 1955. Dr. Howard’s academic career was spent entirely at Cambridge University in England where he worked in various departments, including the Medical Research Council Unit of Nutrition (also known as “the Dunn”), the Department of Pathology and the Department of Medicine. -

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

Theatre at Its Best

SUPPORT THEATRE AT ITS BEST RSC MEMBERS AND SUPPORTERS PRIORITY BOOKING DATES INCREASE YOUR MEMBERSHIP TO TO SHAKESPEARE’S CIRCLE FROM £100 AND: PRIORITY PLUS FROM THURSDAY 17 SEPTEMBER ENJOY A CLOSER RELATIONSHIP WITH THE FULL MEMBERS ONLINE & TELEPHONE FROM MONDAY 21 SEPTEMBER WORLD’S BEST KNOWN THEATRE COMPANY ASSOCIATE MEMBERS ONLINE & TELEPHONE FROM MONDAY 5 OCTOBER DIRECTLY SUPPORT OUR WORK PUBLIC BOOKING FROM MONDAY 19 OCTOBER ON STAGE AND IN CLASSROOMS BENEFIT FROM PRIORITY PLUS BOOKING ATTEND EVENTS WITH ARTISTIC TEAMS FOR INFORMATION OR TO JOIN CONTACT MICHELE COTTISS ON 01789 272283 OR EMAIL [email protected] THANK YOU We are proud of, and grateful to, our many supporters and partners. Their support ensures that we can continue to stage the work of Shakespeare, his contemporaries and the most exciting new writers and performers of today, making every play an event. PUBLIC FUNDERS CORPORATE SUPPORTERS ARTS COUNCIL ENGLAND DEPARTMENT FOR CULTURE, MEDIA AND SPORT HERITAGE LOTTERY FUND NATIONAL LOTTERY THROUGH Supports £5 tickets for 16--25s ARTS COUNCIL ENGLAND CREATIVE LEARNING PARTNERS WWW.RSC.ORG.UK Official Brand Partner 01789 403493 THEATRE AT ITS BEST IMAGE CREDITS: COVER BIRTHDAY FIREWORKS, LUCY BARRIBALL | A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM: DESIGN BY RSC VISUAL COMMUNICATIONS | HAMLET: JOHN COOPER/ARCANGEL | CYMBELINE: PETER JOHNSTON/ARCANGEL | DOCTOR FAUST: HANKA STEIDLE/ARCANGEL | DON QUIXOTE: JACK’S MAN WILLIAM, A MODERN SANCHO PANZA, REMINGTON, FREDERIC (1861-1909) / PRIVATE COLLECTION / PHOTO © CHRISTIE’S IMAGES / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES | THE ALCHEMIST: MIGUEL ANGEL MUNOZ/ARCANGEL NEW FOR 2016: TOP LEFT: PAUL ROBESON IN OTHELLO, 1959 PHOTOGRAPH BY ANGUS MCBEAN © RSC | TOP MIDDLE: COSTUME DESIGN FOR THE TEMPEST, 1978 BY RALPH KOLTAI © RSC | TOP RIGHT: VIVIEN LEIGH AND LAURENCE OLIVIER IN MACBETH, 1955 PHOTOGRAPH FROM ANGUS MCBEAN © RSC | | PreferredPreferred Hotel Partner for Matilda The Musical,, LondonLondon BOTTOM LEFT: HELMET FOR ALAN HOWARD AS CORIOLANUS, 1977. -

Looking Back Cover Feature Screentime

MAY 2011 www.britishclubbangkok.org COVER FEATURE Tennis Championships LOOKING BACK SCREENTIME Songkran Party Dr Who 2011 Britstock Monday Night Club Comedy Night Thurs Night Movies Pancake Races Children’s Movies size 210 x 297 mm. for outpost. May 2011 • • OUTPOST • • 1 GENERAL COMMITTEE REPORTINGS Chairman Front coVER MAY 2011 Jonathan Truslow The British Club’s tennis [email protected] www.britishclubbangkok.org Message from the GM championships this year were 03 A quick update from last month well attended and enormously General Committee enjoyable. The playing was Members exhilarating and the mood was House & Grounds Sarah Allen (Vice-Chairman), Philip competitive, but at no cost to Alexander (Honorary Treasurer), 05 Report on Maintenance and Development the overall spirit of the matches. Paul Cheesman (Honorary Secretary), John Bleho, David Blowers, Martin There was time for the juniors to Carter, Ian Harry, Andrew McLean, Simon Says... play as well, and a party to round the events off. We have devoted Chris Watt What’s been and what’s coming COVER FEATURE 07 two pages this month to a fine Tennis Championships [email protected] LOOKING BACK SCREENTIME Songkran Party Dr Who 2011 Britstock Monday Night Club selection of photos of competitors Comedy Night Thurs Night Movies Pancake Races Children’s Movies SENIOR MANAGERS F&B Morsels young and old in action. General Manager News of a culinary nature 09 Cover photo by Chris Watt with many thanks. Jesper Doepping [email protected] Starting Our 108th Year -

Coriolanus and the Hypostatized Body John JOWETT (Shakespeare Institute – Birmingham University) ______

Copyright © 2007 – IRCL. Tous droits réservés. Les utilisateurs peuvent télécharger et imprimer pour un usage strictement privé. Reproduction soumise à autorisation. Coriolanus and the Hypostatized Body John JOWETT (Shakespeare Institute – Birmingham University) _______________________________________ would like to begin with an image. This image is formative for the way I think of Coriolanus, and indeed it comes from my first experience of seeing it on stage. This Iwas in 1978, when Alan Howard took the lead role. The moment I recall if of his re- entry after going to fight alone in the city of Corioles. In theatre style of the period, the stage was swathed in dry ice. The gates were two huge slabs forming a rear stage wall that slid open. They were prised apart from within by the figure of Coriolanus, mounted high above the stage with arms and legs braced against the city gates, melodramatically backlit from below, half naked, drenched in blood. I am not entirely sure that all these details are correct; this is a memory. But this image sums up some of the things I will be talking about today. It uses the figure of the actor to iconise the body, making it a symbol of heroic slaughter. And it overlaps the idea of the superhuman killer with the idea of the sacrificial victim. The image is a modern visual equivalent in theatre terms of ideas in the play’s language. It seems to me that, as compared with other Shakespeare plays, the theatre is visual and emblematic, and the language is strongly mapped onto an idea of the body that connects with the physical presence of human bodies on stage. -

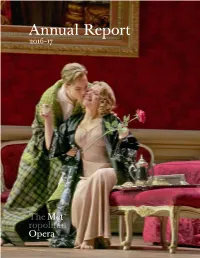

FY17 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2016–17 1 2 4 Introduction 6 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 3 Introduction In the 2016–17 season, the Metropolitan Opera continued to present outstanding grand opera, featuring the world’s finest artists, while maintaining balanced financial results—the third year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and also included five other new stagings, as well as 20 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 11th year, with ten broadcasts reaching approximately 2.3 million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (Live in HD and box office) totaled $111 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All six new productions in the 2016–17 season were the work of distinguished directors who had previous success at the Met. The compelling Opening Night new production of Tristan und Isolde was directed by Mariusz Treliński, who made his Met debut in 2015 with the double bill of Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta and Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle. French-Lebanese director Pierre Audi brought his distinctive vision to Rossini’s final operatic masterpiece Guillaume Tell, following his earlier staging of Verdi’s Attila in 2010. Robert Carsen, who first worked at the Met in 1997 on his popular production of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, directed a riveting new Der Rosenkavalier, the company’s first new staging of Strauss’s grand comedy since 1969. -

Aladdin2005.Pdf

a new version by Bille Brown Director Sean Mathias original score by Gareth Valentine Designer John Napier additional song 'I Believe in You' Choreographer Wayne McGregor music by Elton John & lyrics by Lee Hall Musical Supervisor Gareth Valentine Costumes Mark Bouman Producer David Liddiment Lighting David Hersey Executive Producer Colin Ingram Casting Director Jill Green CDG Sound Fergus O'Hare Production Manager Dominic Fraser Orchestrations Chris Walker Assistant Director Paul Warwick Griffin Assistant Choreographer Laila Diallo Musical Director Kevin Amos Additional script Paul Alexander Designs inspired bythe drawings of Flo Perry First performance at The Old Vic Wednesday 7 December 2005 CARST in ORDER F OR LADD IN 0F AP FE ARANC Am Abbanazar Roger Allam Company Manager (OVTQ Jane Semark Aladdin Neil McDermott Stage Manager Simon Ash Hanky Matthew Wolfenden Deputy Slage Manager Nicole Keighley Panky Andrew Spillett Assistant Stage Managers Martha Mamo Dim Sum Frances Barber Sarah Winborn WidowTwankey Ian McKellen Costume Supervisor Tracey Stiles Princess Kate Gillespie Head of Wardrobe (OVTQ Fiona Lehmann Emperor Paul Grunert Deputy Head of Wardrobe (OVTQ Louise Askins Genie Tee Jaye Wigs Supervisor Joanna Taylor Ensemble Marina Abdeen Head of Wigs Rick Strickland Madalena Alberto Deputy I lead of Wigs Emma Sharp Gary Amers Properties Supervisor Tracey Clarke Alistair David Head of Lighting (OVTC) Stuart Crane Steve Fortune Deputy Head of Lighting (OVTQ Andrew Taylor Emma Harris Head of Stage (OVTQ PJ Holloway Victoria Hinde Deputy -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandardm argins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.