I from LIVING WORLD to a DEAD EARTH: MARS in AMERICAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind Measurements of Martian Dust Devils from Hirise

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 6, EPSC-DPS2011-570, 2011 EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2011 c Author(s) 2011 Wind Measurements of Martian Dust Devils from HiRISE D. S. Choi (1) and C. M. Dundas (2) (1) Department of Planetary Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA ([email protected]) (2) United States Geological Survey, Flagstaff, AZ, USA Abstract servation crosses an active feature such as a dust devil, changes in the active feature are apparent from the We report direct measurements of the winds within three separate views. Treating the dust clouds as pas- Martian dust devils from HiRISE imagery. The cen- sive tracers of motion then allows for the direct mea- tral color swath of the HiRISE instrument observes surement of wind velocities. the surface by using separate CCDs and color filters in We utilize measurements from manual (hand-eye) rapid cadence. Active features, such as a dust devil, tracking of the clouds through image blinking, as appear in motion when serendipitously captured by well as automated correlation methods [9]. Typically, this region of the instrument. Our measurements re- manual measurements are more successful than au- veal clear circulation within the vortices, and that the tomated measurements. The relatively diffuse dust majority of overall wind magnitude within a dust devil clouds, combined with the static background terrain, 1 is between 10 and 30 m s− . cause the automated software to incorrectly report the movement as stationary. Successful automated results were obtained from images with more substantial dust 1. Introduction clouds and relatively featureless background terrain. Direct measurements of the winds within a Martian dust devil [1] are challenging to obtain. -

THE PLANETARY REPORT FAREWELL, SEPTEMBER EQUINOX 2017 VOLUME 37, NUMBER 3 CASSINI Planetary.Org CELEBRATING a LEGACY of DISCOVERIES

THE PLANETARY REPORT FAREWELL, SEPTEMBER EQUINOX 2017 VOLUME 37, NUMBER 3 CASSINI planetary.org CELEBRATING A LEGACY OF DISCOVERIES ATMOSPHERIC CHANGES C DYNAMIC RINGS C COMPLICATED TITAN C ACTIVE ENCELADUS ABOUT THIS ISSUE LINDA J. SPILKER is Cassini project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. IN 2004, Cassini, the most distant planetary seafloor. As a bonus, it has revealed jets of orbiter ever launched by humanity, arrived at water vapor and ice particles shooting out of Saturn. For 13 years, through its primary and fractures at the moon’s south pole. two extended missions, this spacecraft has These discoveries have fundamentally been making astonishing discoveries, reshap- altered many of our concepts of where life ing and changing our understanding of this may be found in our solar system. Cassini’s unique planetary system within our larger observations at Enceladus and Titan have made system of unique worlds. A few months ater exploring these ocean worlds a major focus for arrival, Cassini released Huygens, European planetary science. New insights from these dis- Space Agency’s parachuted probe built to coveries also have implications for potentially study the atmosphere and surface of Titan habitable worlds beyond our solar system. and image its surface for the very first time. In this special issue of The Planetary Report, a handful of Cassini scientists share some results from their studies of Saturn and its moons. Because there’s no way to fit every- thing into this slim volume, they’ve focused on a few highlights. Meanwhile, Cassini continues performing its Grand Finale orbits between the rings and the top of Saturn’s atmosphere, circling the planet once every 6.5 days. -

Selection of the Insight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript InSight Landing Site Paper v9 Rev.docx Click here to view linked References Selection of the InSight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N. Warner1,2, I. J. Daubar1, R. Fergason3, R. Kirk3, R. Beyer4, A. Huertas1, S. Piqueux1, N. E. Putzig5, B. A. Campbell6, G. A. Morgan6, C. Charalambous7, W. T. Pike7, K. Gwinner8, F. Calef1, D. Kass1, M. Mischna1, J. Ashley1, C. Bloom1,9, N. Wigton1,10, T. Hare3, C. Schwartz1, H. Gengl1, L. Redmond1,11, M. Trautman1,12, J. Sweeney2, C. Grima11, I. B. Smith5, E. Sklyanskiy1, M. Lisano1, J. Benardino1, S. Smrekar1, P. Lognonné13, W. B. Banerdt1 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109 2State University of New York at Geneseo, Department of Geological Sciences, 1 College Circle, Geneseo, NY 14454 3Astrogeology Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Dr., Flagstaff, AZ 86001 4Sagan Center at the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035 5Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302; Now at Planetary Science Institute, Lakewood, CO 80401 6Smithsonian Institution, NASM CEPS, 6th at Independence SW, Washington, DC, 20560 7Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Imperial College, South Kensington Campus, London 8German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Planetary Research, 12489 Berlin, Germany 9Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA; Now at Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA 98926 10Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996 11Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 12MS GIS Program, University of Redlands, 1200 E. Colton Ave., Redlands, CA 92373-0999 13Institut Physique du Globe de Paris, Paris Cité, Université Paris Sorbonne, France Diderot Submitted to Space Science Reviews, Special InSight Issue v. -

And Abiogenesis

Historical Development of the Distinction between Bio- and Abiogenesis. Robert B. Sheldon NASA/MSFC/NSSTC, 320 Sparkman Dr, Huntsville, AL, USA ABSTRACT Early greek philosophers laid the philosophical foundations of the distinction between bio and abiogenesis, when they debated organic and non-organic explanations for natural phenomena. Plato and Aristotle gave organic, or purpose-driven explanations for physical phenomena, whereas the materialist school of Democritus and Epicurus gave non-organic, or materialist explanations. These competing schools have alternated in popularity through history, with the present era dominated by epicurean schools of thought. Present controversies concerning evidence for exobiology and biogenesis have many aspects which reflect this millennial debate. Therefore this paper traces a selected history of this debate with some modern, 20th century developments due to quantum mechanics. It ¯nishes with an application of quantum information theory to several exobiology debates. Keywords: Biogenesis, Abiogenesis, Aristotle, Epicurus, Materialism, Information Theory 1. INTRODUCTION & ANCIENT HISTORY 1.1. Plato and Aristotle Both Plato and Aristotle believed that purpose was an essential ingredient in any scienti¯c explanation, or teleology in philosophical nomenclature. Therefore all explanations, said Aristotle, answer four basic questions: what is it made of, what does it represent, who made it, and why was it made, which have the nomenclature material, formal, e±cient and ¯nal causes.1 This aristotelean framework shaped the terms of the scienti¯c enquiry, invisibly directing greek science for over 500 years. For example, \organic" or \¯nal" causes were often deemed su±cient to explain natural phenomena, so that a rock fell when released from rest because it \desired" its own kind, the earth, over unlike elements such as air, water or ¯re. -

Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of Volatiles in Permanently Cold Areas of Mercury’S North Polar Region

Icarus 281 (2017) 19–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of volatiles in permanently cold areas of Mercury’s north polar region ∗ M.L. Delitsky a, , D.A. Paige b, M.A. Siegler c, E.R. Harju b,f, D. Schriver b, R.E. Johnson d, P. Travnicek e a California Specialty Engineering, Pasadena, CA b Dept of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA c Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ d Dept of Engineering Physics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA e Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA f Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft during its flyby and orbital observations of Mercury in 2008– Received 3 January 2016 2015 indicated the presence of cold icy materials hiding in permanently-shadowed craters in Mercury’s Revised 29 July 2016 north polar region. These icy condensed volatiles are thought to be composed of water ice and frozen Accepted 2 August 2016 organics that can persist over long geologic timescales and evolve under the influence of the Mercury Available online 4 August 2016 space environment. Polar ices never see solar photons because at such high latitudes, sunlight cannot Keywords: reach over the crater rims. The craters maintain a permanently cold environment for the ices to persist. Mercury surface ices magnetospheres However, the magnetosphere will supply a beam of ions and electrons that can reach the frozen volatiles radiolysis and induce ice chemistry. -

Magnetic Planets and Magnetic Planets and How Mars Lost Its

Magnetic Planets and How Mars Lost Its Atmosphere Bob Lin Physics Department & Space Sciences Laboratory Universityyf of Calif ornia, Berkeley Also (visiting) School of Space Research Kyung Hee University, Korea Thanks to the MGS, MAVEN, and LP teams Earth’s Magnetic Field The Earth’s Magnetosphere Explorer 35 (1967) Lunar Shadowing Apollo 15 Mission -1971 Lunar Rover -> <- Jim Arnold's Gamma-ray Spectrometer <- Apollo 15 Subsatellite -> <= SIM (Scientific Instrument Module) Lunar Shadowing <= Downward electrons <= Upward electrons <= Ratio of Upward to DdltDownward electrons Electron Reflection Electron Trajectory Converging Magnetic Fields Secondary Electron ---- ---- - dv||RemotelydU SensingdB Surface MagneticB Fields by m + e + μ = 0⇒sin 2 α = LP []1- eΔU E Planetary Electron Reflection Magnetometryc (PERM) dt ds ds BSurf Apollo 15 & 16 Subsatellites Electron Reflectometry OneHowever, of the the great Apollo surprises 15 & 16 from Subsatellite Apollo was magnetic the discovery data set of paleomagneticis very sparse and fields confined in the lunar within crust 35 degrees. Their existence of the suggestsequator. Attempts that magnetic to correlate fields atsurface the Moon magnetic were muchfields with strongerspecific geologic in the past features than they were are largely today. unsuccessful. Mars Observer (1992-3) – disappeared 3 days before Mars orbit insertion Mars Global Surveyy(or (MGS) 1996-2006 MGS Mag/ER team Current state of knowledge • Very strong crustal fields measured from orbit: – Discovered by MGS: ~10 times stronger -

The Mystery of Methane on Mars and Titan

The Mystery of Methane on Mars & Titan By Sushil K. Atreya MARS has long been thought of as a possible abode of life. The discovery of methane in its atmosphere has rekindled those visions. The visible face of Mars looks nearly static, apart from a few wispy clouds (white). But the methane hints at a beehive of biological or geochemical activity underground. Of all the planets in the solar system other than Earth, own way, revealing either that we are not alone in the universe Mars has arguably the greatest potential for life, either extinct or that both Mars and Titan harbor large underground bodies or extant. It resembles Earth in so many ways: its formation of water together with unexpected levels of geochemical activ- process, its early climate history, its reservoirs of water, its vol- ity. Understanding the origin and fate of methane on these bod- canoes and other geologic processes. Microorganisms would fit ies will provide crucial clues to the processes that shape the right in. Another planetary body, Saturn’s largest moon Titan, formation, evolution and habitability of terrestrial worlds in also routinely comes up in discussions of extraterrestrial biology. this solar system and possibly in others. In its primordial past, Titan possessed conditions conducive to Methane (CH4) is abundant on the giant planets—Jupiter, the formation of molecular precursors of life, and some scientists Saturn, Uranus and Neptune—where it was the product of chem- believe it may have been alive then and might even be alive now. ical processing of primordial solar nebula material. On Earth, To add intrigue to these possibilities, astronomers studying though, methane is special. -

Spacecraft Imaging for Amateurs an International Community of Space

Planetary Close-ups emily lakdawalla Spacecraft Imaging for Amateurs An international community of space This is Mars’s Big Sky Country, a windswept, nearly featureless plain. Tiny ripples in the rust-colored sand march farther than the eye can see, to a horizon so fl at one might be able to see the curvature of the planet. As far as anyone knows, those ripples have not budged in eons. But all is not still; gaze upward, and you might be surprised by the rapid motion overhead, where feathery cirrus clouds, frosty with bright crystals of water ice, fl oat on high Martian winds. The scene is from Meridiani Planum, composed from eight images captured by the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity just before she reached a deep crater named Victoria, on the 950th Martian day of her mission. But the beautiful image was not created by anyone on the Mars Exploration Rover team; no scientist would likely have Earthbound produced it, because it owes its beauty as much to art as it observers never does to science. see Mars as a The image is the collaborative creation of a whole crescent, but amateur-imagesmith community; six people, each from spacecraft do. a diff erent country, had a hand in it. Twelve hours after The author cre- Opportunity took the photos, the data had been received on ated this view Earth and posted to the internet. Within another 17 hours, from six images rover fans had found the photos, assembled the mosaic, taken by Viking and shaded the sand and sky based on color photos Oppor- Orbiter 2 in tunity had taken of a similar landscape the day before. -

AIAA Fellows

AIAA Fellows The first 23 Fellows of the Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences (I) were elected on 31 January 1934. They were: Joseph S. Ames, Karl Arnstein, Lyman J. Briggs, Charles H. Chatfield, Walter S. Diehl, Donald W. Douglas, Hugh L. Dryden, C.L. Egtvedt, Alexander Klemin, Isaac Laddon, George Lewis, Glenn L. Martin, Lessiter C. Milburn, Max Munk, John K. Northrop, Arthur Nutt, Sylvanus Albert Reed, Holden C. Richardson, Igor I. Sikorsky, Charles F. Taylor, Theodore von Kármán, Fred Weick, Albert Zahm. Dr. von Kármán also had the distinction of being the first Fellow of the American Rocket Society (A) when it instituted the grade of Fellow member in 1949. The following year the ARS elected as Fellows: C.M. Bolster, Louis Dunn, G. Edward Pendray, Maurice J. Zucrow, and Fritz Zwicky. Fellows are persons of distinction in aeronautics or astronautics who have made notable and valuable contributions to the arts, sciences, or technology thereof. A special Fellow Grade Committee reviews Associate Fellow nominees from the membership and makes recommendations to the Board of Directors, which makes the final selections. One Fellow for every 1000 voting members is elected each year. There have been 1980 distinguished persons elected since the inception of this Honor. AIAA Fellows include: A Arnold D. Aldrich 1990 A.L. Antonio 1959 (A) James A. Abrahamson 1997 E.C. “Pete” Aldridge, Jr. 1991 Winfield H. Arata, Jr. 1991 H. Norman Abramson 1970 Buzz Aldrin 1968 Johann Arbocz 2002 Frederick Abbink 2007 Kyle T. Alfriend 1988 Mark Ardema 2006 Ira H. Abbott 1947 (I) Douglas Allen 2010 Brian Argrow 2016 Malcolm J. -

The Analysis of Life Struggle in Andy Weir's

THE ANALYSIS OF LIFE STRUGGLE IN ANDY WEIR‘S NOVEL THE MARTIAN A THESIS BY ALEMINA BR KABAN REG. NO. 140721012 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA THE ANALYSIS OF LIFE STRUGGLE IN ANDY WEIR‘S NOVEL THE MARTIAN A THESIS BY ALEMINA BR KABAN REG. NO. 140721012 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Drs. Parlindungan Purba,M.Hum. Riko Andika Pohan, S.S., M.Hum. NIP.1963021619 89031003001 NIP. 1984060920150410010016026 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head, Secretary, Prof. T.Silvana Sinar,Dipl.TEFL,MA.,Ph.D Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A. Ph.D. NIP. 19571117 198303 2 002 NIP. 19750209 200812 1 002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara, Medan. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on July 6th, 2018 Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP.19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D __________________ Drs. Parlindungan Purba, M.Hum. -

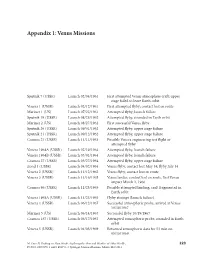

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Infrared Experiments for Spaceborne Planetary Atmospheres Research Full Report

NASA Technical Memorandum 84414 Infrared Experiments for Spaceborne Planetary Atmospheres Research Full Report Infrared Experiments Working Group NOVEMBER 1981 NASA NASA Technical Memorandum 84414 Infrared Experiments for Spaceborne Planetary Atmospheres Research Full Report Infrared Experiments Working Group Jet Propulsion Laboratory Pasadena, California NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Information Branch 1981 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Summary of Principal Conclusions and Recommendations Chapter I The Role of Infrared Sensing in Atmospheric Science Chapter II Review of Existing Infrared Measurement Techniques Chapter III Critical Comparison of Proposed Measurement Techniques Chapter IV Conclusions and Recommended Instrument Developments Appendices: A Critical Technologies B Applicability of Atmospheric Infrared Instrumentation to Surface Science C Supporting Studies in Data Analysis and Numerical Modeling D Description of Planned Earth Orbital Platforms ii PREFACE Experiments conducted in the infrared spectral region provide a powerful tool for the study of the composition, structure and dynamics of planetary atmospheres. However, the field has become highly complex, especially that part associated with spacecraft sensing, and the range of technologies used so diverse that it is difficult to determine which of the available methods for making a particular measurement is to be preferred, even for those deeply involved in the field. Unfortunately, the realities of the age demand that some selectivity be employed; not all approaches can be supported. Furthermore, the chosen methods are generally sufficiently untried that long pre-flight developments are neces- sary if viable proposals are to be written for future flight opportunities. These considerations clearly lead to a program of developments which must be coordinated on a national scale.