Rocking the Sochi Olympics Narrative: Boris Nemtsov and Putin's Sovereignty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPERATION NEMTSOV”: 307 Disinformation, Confusion MARCH and Some Worrying Hypotheses 2015

Centro de Estudios y Documentación InternacionalesCentro de Barcelona E-ISSN 2014-0843 D.L.: B-8438-2012 opiniónEuropa “OPERATION NEMTSOV”: 307 Disinformation, confusion MARCH and some worrying hypotheses 2015 Nicolás de Pedro, Research Fellow, CIDOB Marta Ter, Head of the North Caucasus department at the Lliga dels Drets dels Pobles he investigation into the assassination of Boris Nemtsov reminds previ- ous ones on high-profile political killings, although the uncertainties grow with every new revelation. The verified, documented connec- Ttion between the main suspect, Zaur Dadayev, and Ramzan Kadyrov, Chechen strongman and close ally of Putin strengthens the theory linking the crime to the Kremlin and suggests possible internal fighting within the state security apparatus. Nemtsov joins a long list of critics and opponents who have been assassinated in the last fifteen years. Among the most prominent are:Sergey Yushenkov, member of parliament for the Liberal Russia party (assassinated on April 17th, 2003); Yuri Shchekochikhin, journalist on the Novaya Gazeta (July 3rd, 2003); Paul Klebnikov, US journalist of Russian origin and editor of the Russian edition of Forbes (July 9th, 2004); Anna Politkovskaya, journalist for Novaya Gazeta (October 7th, 2006); Alexander Litvinenko, former KGB/FSB agent (November 23rd, 2006); and Na- talya Estemirova, human rights activist for the Chechen branch of the NGO Me- morial (July 15th, 2009). Each of these assassinations has its own particularities, but none has been properly explained and all of the victims were people who dis- comfited the Kremlin. Despite this, political motivations and possible connections with state apparatus are the only lines of investigation that have been systemati- cally ignored or explicitly denied in all of these cases. -

Boris Nemtsov 27 February 2015 Moscow, Russia

Boris Nemtsov 27 February 2015 Moscow, Russia the fight against corruption, embezzlement and fraud, claiming that the whole system built by Putin was akin to a mafia. In 2009, he discovered that one of Putin’s allies, Mayor of Moscow City Yury Luzhkov, BORIS and his wife, Yelena Baturina, were engaged in fraudulent business practices. According to the results of his investigation, Baturina had become a billionaire with the help of her husband’s connections. Her real-estate devel- opment company, Inteco, had invested in the construction of dozens of housing complexes in Moscow. Other investors were keen to part- ner with Baturina because she was able to use NEMTSOV her networks to secure permission from the Moscow government to build apartment build- ings, which were the most problematic and It was nearing midnight on 27 February 2015, and the expensive construction projects for developers. stars atop the Kremlin towers shone with their charac- Nemtsov’s report revealed the success of teristic bright-red light. Boris Nemtsov and his partner, Baturina’s business empire to be related to the Anna Duritskaya, were walking along Bolshoy Moskovo- tax benefits she received directly from Moscow retsky Bridge. It was a cold night, and the view from the City government and from lucrative govern- bridge would have been breathtaking. ment tenders won by Inteco. A snowplough passed slowly by the couple, obscuring the scene and probably muffling the sound of the gunshots fired from a side stairway to the bridge. The 55-year-old Nemtsov, a well-known Russian politician, anti-corrup- tion activist and a fierce critic of Vladimir Putin, fell to the ground with four bullets in his back. -

Russian Aggression Against Ukraine and the West’S Policy Response

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee Subcommittee on Europe and Regional Security Cooperation Statement for the Record Russian Aggression against Ukraine and the West’s Policy Response Steven Pifer Senior Fellow, Center on the United States and Europe The Brookings Institution March 4, 2015 1 Russian Aggression against Ukraine and the West’s Policy Response Introduction Mr. Chairman, Senator Shaheen, distinguished members of the subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to testify on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, and the U.S. and West’s policy response. What began as an internal Ukrainian political dispute became a Ukraine-Russia crisis in early 2014. Since then, Moscow has used military force to seize Crimea, supported armed separatists and ultimately sent regular Russian army units into eastern Ukraine. A ceasefire agreement was reached in Minsk last September, but the separatists and Russians failed to implement its terms. The Minsk II ceasefire agreed on February 12 may now be taking effect but seems fragile at best. Implementing other terms of the agreement will prove difficult. Driving Russia’s aggression has been a mix of geopolitical and domestic political considerations. The Kremlin’s goal over the past year appears to have been to destabilize and distract the Ukrainian government, in order keep that government from addressing its pressing economic, financial and other challenges as well as from drawing closer to the European Union through implementation of the EU-Ukraine association agreement. Beyond Ukraine, the United States and Europe face a broader Russia problem. Moscow has operated its military forces in a more provocative manner near NATO members and has asserted a right to “protect” ethnic Russians and Russian speakers wherever they are located and whatever their citizenship. -

Of the Conventional Wisdom

M ASSAC H US E TTS INSTITUT E O F T E C H NO L O G Y M ASSAC H US E TTS INSTITUT E O F T E C H NO L O G Y December 2007 M IT Ce NT er F O R I NT er NATIONA L S TU D I E S 07-22 of the Conventional Wisdom Russia: An Energy Superpower? Carol R. Saivetz MIT Center for International Studies s Vladimir Putin nears the end of his second term as Russian Apresident, it is clear that energy exports have become a major component of a resurgent Russia’s foreign policy. According to the conventional wisdom, Russia’s vast resources make it a superpower to be reckoned with. Not only is it a major supplier of natural gas to the states of the former Soviet Union, it sells oil and natural gas to Europe and it has made new contract commitments for both oil and gas to China. Additionally, as the January 2006 cut-off of gas to Ukraine, the January 2007 oil and gas cut-off to Belarus, and Gazprom’s threat (again) to Ukraine in the wake of the September 2007 parliamentary elections indicate, Russia is willing to use its resources for political purposes. The conventional wisdom continues that none of this is surprising. Putin acceded to the Russian presidency resolved to restore Russia’s superpower status and to use energy Center for International Studies to that end. The Russian Federation’s Energy Strategy, dated August 28, 2003, formally Massachusetts Institute of Technology Building E38-200 states that Russia’s natural resources should be a fundamental element in Moscow’s diplo- 292 Main Street macy and that Russia’s position in global energy markets should be strengthened.1 In his Cambridge, MA 02139 own dissertation, Putin argued that the energy sector should be guided by the state and T: 617.253.8093 used to promote Russia’s national interests.2 And, the rector of the Mining Institute in F: 617.253.9330 which Putin wrote his dissertation and currently one of his energy advisors wrote: “In the [email protected] specific circumstances the world finds itself in today, the most important resources are web.mit.edu/cis/ hydrocarbons . -

Gazprom's New Weakness Offers Opportunity by Anders Åslund

CASE Network E-briefs 6/2009 June 2009 Gazprom's New Weakness Offers Opportunity By Anders Åslund Gazprom has gone from being a great commercial hope Gazprom also lacks a comparative advantage in the to an ailing giant. Gazprom's owners need to face up to transportation of gas. No other company has so many the crisis and institute reforms. explosions on major pipelines. Moreover, Gazprom is notorious for including shady intermediaries, which A year ago, Gazprom was the third‐most valuable later prompt the company to shut off its deliveries. company in the world with a market capitalization of over $350 billion. Today, it has shrunk by two‐thirds to Finally, few companies procure at more excessive about $120 billion, declining to become the world's prices. When Gazprom built Blue Stream, Hermitage 40th‐largest company, even though it still accounts for Capital Management showed that Gazprom's cost per about 20 percent of Russia's market capitalization and kilometer of pipeline was three times greater than on roughly 10 percent of its gross domestic product. the Turkish side. This seems to be a standard excess cost for Gazprom. In the first quarter, the country's gas exports plunged by 56 percent from last year, compelling Gazprom to cut its Gazprom's only comparative advantage is its control of production ever more. During the first 10 days of May, it one‐quarter of the world's gas reserves, but these plummeted by 34 percent. Even in the fourth quarter of reserves do not actually belong to the company. They 2008 ‐‐ when production, exports and prices were still are only licenses granted by the government. -

RUSSIA WATCH No.2, August 2000 Graham T

RUSSIA WATCH No.2, August 2000 Graham T. Allison, Director Editor: Ben Dunlap Strengthening Democratic Institutions Project Production Director: Melissa C..Carr John F. Kennedy School of Government Researcher: Emily Van Buskirk Harvard University Production Assistant: Emily Goodhue SPOTLIGHT ON RUSSIA’S OLIGARCHS On July 28 Russian President Vladimir Putin met with 21 of Russia’s most influ- ential businessmen to “redefine the relationship between the state and big busi- ness.” At that meeting, Putin assured the tycoons that privatization results would remained unchallenged, but stopped far short of offering a general amnesty for crimes committed in that process. He opened the meeting by saying: “I only want to draw your attention straightaway to the fact that you have yourselves formed this very state, to a large extent through political and quasi-political structures under your control.” Putin assured the oligarchs that recent investi- The Kremlin roundtable comes at a crucial time for the oligarchs. In the last gations were not part of a policy of attacking big business, but said he would not try to restrict two months, many of them have found themselves subjects of investigations prosecutors who launch such cases. by the General Prosecutor’s Office, Tax Police, and Federal Security Serv- ice. After years of cozying up to the government, buying up the state’s most valuable resources in noncompetitive bidding, receiving state-guaranteed loans with little accountability, and flouting the country’s tax laws with imp u- nity, the heads of some of Russia’s leading financial-industrial groups have been thrust under the spotlight. -

Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam As a Tool of the Kremlin?

Notes de l’Ifri Russie.Nei.Visions 99 Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam as a Tool of the Kremlin? Marlène LARUELLE March 2017 Russia/NIS Center The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the few French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European and broader international debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. This text is published with the support of DGRIS (Directorate General for International Relations and Strategy) under “Observatoire Russie, Europe orientale et Caucase”. ISBN: 978-2-36567-681-6 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2017 How to quote this document: Marlène Laruelle, “Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam as a Tool of the Kremlin?”, Russie.Nei.Visions, No. 99, Ifri, March 2017. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15—FRANCE Tel.: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00—Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Ifri-Bruxelles Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 1000—Brussels—BELGIUM Tel.: +32 (0)2 238 51 10—Fax: +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Russie.Nei.Visions Russie.Nei.Visions is an online collection dedicated to Russia and the other new independent states (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). -

Russia 2020 Human Rights Report

RUSSIA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Russian Federation has a highly centralized, authoritarian political system dominated by President Vladimir Putin. The bicameral Federal Assembly consists of a directly elected lower house (State Duma) and an appointed upper house (Federation Council), both of which lack independence from the executive. The 2016 State Duma elections and the 2018 presidential election were marked by accusations of government interference and manipulation of the electoral process, including the exclusion of meaningful opposition candidates. On July 1, a national vote held on constitutional amendments did not meet internationally recognized electoral standards. The Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Security Service, the Investigative Committee, the Office of the Prosecutor General, and the National Guard are responsible for law enforcement. The Federal Security Service is responsible for state security, counterintelligence, and counterterrorism, as well as for fighting organized crime and corruption. The national police force, under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, is responsible for combating all crime. The National Guard assists the Federal Security Service’s Border Guard Service in securing borders, administers gun control, combats terrorism and organized crime, protects public order, and guards important state facilities. The National Guard also participates in armed defense of the country’s territory in coordination with Ministry of Defense forces. Except in rare cases, security forces generally report to civilian authorities. National-level civilian authorities have, at best, limited control over security forces in the Republic of Chechnya, which are accountable only to the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov. Members of the Russian security forces committed numerous human rights abuses. -

A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects the Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society

The Russian Opposition: A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects The Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society By Julia Pettengill Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 1 First published in 2012 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society 8th Floor – Parker Tower, 43-49 Parker Street, London, WC2B 5PS Tel: 020 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2012 All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its directors Designed by Genium, www.geniumcreative.com ISBN 978-1-909035-01-0 2 About The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society: A cross-partisan, British think-tank. Our founders and supporters are united by a common interest in fostering a strong British, European and American commitment towards freedom, liberty, constitutional democracy, human rights, governmental and institutional reform and a robust foreign, security and defence policy and transatlantic alliance. The Henry Jackson Society is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales under company number 07465741 and a charity registered in England and Wales under registered charity number 1140489. For more information about Henry Jackson Society activities, our research programme and public events please see www.henryjacksonsociety.org. 3 CONTENTS Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 5 About the Author 6 About the Russia Studies Centre 6 Acknowledgements 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 11 CHAPTER -

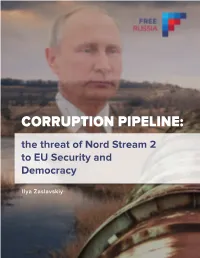

CORRUPTION PIPELINE: the Threat of Nord Stream 2 to EU Security and Democracy

CORRUPTION PIPELINE: the threat of Nord Stream 2 to EU Security and Democracy Ilya Zaslavskiy Ilya Zaslavskiy | Corruption Pipeline: The Threat of Nord Stream 2 to EU Security and Democracy | Free Russia Foundation, 2017 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 NS2 AS A TOOL OF KREMLIN’S POLITICAL INFLUENCE AGAINST NEIGHBORS AND CORRUPTION 4 ACTUAL RESULTS OF NORD STREAM 1 7 ROOTS OF GAZPROM’S APPEASEMENT IN EUROPE 10 IMPLICATIONS OF NS2 FOR WESTERN POLICY-MAKERS 16 Corruption Pipeline: The Threat of Nord Stream 2 CONTENTS to EU Security and Democracy I. INTRODUCTION his paper is a continuation of publications on security architecture. This Moscow-led pipeline Tthe Kremlin’s subversive activity in Europe seemingly being served as a free and lucrative prepared by Free Russia Foundation. The first gift to European energy corporations in reality paper, The Kremlin’s Gas Games in Europe, comes at the expense of taxpayers and the published jointly with the Atlantic Council, reasonable long-term development of gas looked at Gazprom’s overall current tactics in resources in Russia. Nord Stream 1 and 2 have Europe, including its pipeline plans, energy already started bringing the Kremlin’s business propaganda, and other policies.1 However, after practices and political cooptation to Europe, and our presentations in the US and Europe earlier they will further undermine EU aspirations for this year,2 we realized that a separate paper better governance, democratic institutions and specifically focused on certain aspects of Nord security. Stream 2 was required. To understand why this development is accepted Gazprom and its Western partners that are slated in Germany, and meets with weak and confused to benefit from Nord Stream 2 are aggressively resistance in the EU, it is important to look at advancing the pipeline as a purely commercial the roots of the friendship between big Western project that will only bring benefits to Europe. -

Committee Secretary Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade PO Box 6021 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600, Australia

Committee Secretary Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade PO Box 6021 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600, Australia 30 January 2020 Dear Members of the Committee, It is my privilege to write to you as part of your ongoing Parliamentary inquiry in strong support of the passage of legislation comparable to the United States Magnitsky Act of 2012. By way of brief background, I am a Russian journalist, historian, and political activist, and was a candidate for the Russian Parliament representing the pro-democracy opposition. For more than fifteen years, I had the honour of working with the late Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, and I currently chair the Boris Nemtsov Foundation for Freedom. Below this letter you will find an addendum with a more detailed biography for your reference. On 31 December 2019, Russia marked two decades under Vladimir Putin’s rule. An entire generation has grown up not knowing any other ruler or political reality. These years have been marked, above all, by the dismantling of political freedoms and of our country’s nascent democratic institutions. Freedom of the media has been the first target of Mr. Putin’s regime, with all independent nationwide television channels shut down or taken over within the first three years. Today, Russian television – still the primary source of information for the majority of citizens – provides a continuous propaganda drumbeat, with laudatory coverage of the authorities and with attacks on the Kremlin’s opponents who are denounced as “traitors” and “foreign agents”. Indeed, “foreign agent” is now an official designation, introduced by a recent law designed to target non-governmental organisations. -

On December 31, 1999,Yeltsin's Russia Became Putin's Russia

PROLOGUE n December 31, 1999,Yeltsin’s Russia became Putin’s Russia. Boris Yeltsin—a political maverick who until the end tried to Oplay the mutually exclusive roles of democrat and tsar, who made revolutionary frenzy and turmoil his way of survival—unexpect- edly left the Kremlin and handed over power, like a New Year’s gift, to Vladimir Putin, an unknown former intelligence officer who had hardly ever dreamed of becoming a Russian leader. Yeltsin—tired and sick, disoriented and having lost his stamina— apparently understood that he could no longer keep power in his fist. It was a painful and dramatic decision for a politician for whom nonstop struggle for power and domination was the substance of life and his main ambition. His failing health and numerous heart attacks, however, were not the main reasons behind his unexpected resignation. The moment came when Yeltsin could not control the situation much longer and—more important—he did not know how to deal with the new challenges Russia was facing. He had been accustomed to making breakthroughs, to defeating his enemies, to overcoming obstacles. He was not prepared for state building, for the effort of everyday governance, for consensus making, for knitting a new national unity. By nature he was a terminator, not a transformational leader. It was time for him to gra- ciously bow out and hand over power to his successor. And Russia had to live through a time of real suspense while the Kremlin was preparing the transfer of power. The new Russian leader Vladimir Putin has become a symbol of a staggering mix of continuity and change.