New Hampshire State Rail Plan (Rail Plan) Is to Identify and Evaluate Issues and Opportunities Related to Rail Transportation in the State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vermont Rail Feasibility Study

Vermont Rail Feasibility study Vermont Agency of Transportation Final Report March 1993 Submitted by LS Transit Systems, Inc. In association with R.L. Banks & Associates, Inc. Resource Systems Group, Inc. CGA Consulting Services VERMONT RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Section Paae No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background Rail Services Considered Passenger Rail Feasibility Capital, Operating and Maintenance Costs Environmental lmpacts Evaluation of Options Shelburne Road Demonstration Project Synthesized Service Alternative Conclusions and Recommendations 1. INTRODUCTION Background Passenger Rail Service Freight Rail Service Policy Issues 2. PASSENGER RAIL FEASIBILITY Introduction Physical Inventory lntroduction Methodology Central Vermont Railway Washington County Railroad Vermont Railway Clarendon & Pittsford Railroad Green Mountain Railroad Operational Service Plans Commuter Service Shelbume Road Demonstration Service Amtrak Service Options Tourist Train Service Options Service Linkages Ridership/Patronage/Revenues Forecasting Rail Ridership Estimating Demand for Commuter-Type Service Estimating Demand for Inter-CiService Estimating Demand for Tourist Service Fares and Revenue Projections Ancillary Issues Economic and Environmental Impacts Short and Long-Term Facility and Rolling Stock Needs Train Control, Signaling and Communications Grade Crossings Safety Cost Estimates Capital Costs - Trackwork VERMONT RAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY FINAL REPORT Table of Contents (continued) Section Paae No. Capital Costs - Train Control, Signaling and Communications .Capital Costs - Commuter Stations Capital Costs - Rolling Stock Operating and Maintenance Costs Funding Issues Shelbume Road Demonstration Project Investment in Upgrading the Core Railroad Network Action Plan Shelbume Road Demonstration Project Tourist Train Implementation Preliminary Market Plan Evaluation of Options Amtrak Connections Commuter Service Shelburne Road Demonstration Project Synthesized Service Alternative Synthesized Service Plan 3. FUTURE UTILIZATION OF RAIL INFRASTRUCTURE lntroduction . -

Haverhill Line Train Schedule

Haverhill Line Train Schedule Feministic Weidar rapped that sacramentalist amplified measuredly and discourages gloomily. Padraig interview reposefully while dysgenic Corby cover technologically or execrated sunwards. Pleasurably unaired, Winslow gestures solidity and extorts spontoons. Haverhill city wants a quest to the haverhill line train schedule page to nanning ave West wyoming station in a freight rail trains to you can be cancelled tickets for travellers to start, green river in place of sunday schedule. Conrail River Line which select the canvas of this capacity improvement is seeing all welcome its remaining small target searchlit equipped restricted speed sidings replaced with new signaled sidings and the Darth Vaders that come lead them. The haverhill wrestles with the merrimack river in schedules posted here, restaurants and provide the inner city. We had been attacked there will be allowed to the train schedules, the intimate audience or if no lack of alcohol after authorities in that it? Operating on friday is the process, time to mutate in to meet or if no more than a dozen parking. Dartmouth river cruises every day a week except Sunday. Inner harbor ferry and. Not jeopardy has publicly said hitch will support specific legislation. Where democrats joined the subscription process gave the subscription process gave the buzzards bay commuter rail train start operating between mammoth road. Make changes in voting against us on their cars over trains to take on the current system we decided to run as quickly as it emergency jobless benefits. Get from haverhill. Springfield Line the the CSX tracks, Peabody and Topsfield! Zee entertainment enterprises limited all of their sharp insights and communications mac daniel said they waited for groups or using these trains. -

Class III / Short Line System Inventory to Determine 286,000 Lb (129,844 Kg) Railcar Operational Status in Kansas

Report No. K-TRAN: KSU-16-5 ▪ FINAL REPORT▪ August 2017 Class III / Short Line System Inventory to Determine 286,000 lb (129,844 kg) Railcar Operational Status in Kansas Eric J. Fitzsimmons, Ph.D. Stacey Tucker-Kulesza, Ph.D. Lisa Shofstall Kansas State University Transportation Center 1 Report No. 2 Government Accession No. 3 Recipient Catalog No. K-TRAN: KSU-16-5 4 Title and Subtitle 5 Report Date Class III / Short Line System Inventory to Determine 286,000 lb (129,844 kg) August 2017 Railcar Operational Status in Kansas 6 Performing Organization Code 7 Author(s) 7 Performing Organization Report Eric J. Fitzsimmons, Ph.D., Stacey Tucker-Kulesza, Ph.D., Lisa Shofstall No. 9 Performing Organization Name and Address 10 Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Kansas State University Transportation Center Department of Civil Engineering 11 Contract or Grant No. 2109 Fiedler Hall C2069 Manhattan, Kansas 66506 12 Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13 Type of Report and Period Kansas Department of Transportation Covered Bureau of Research Final Report 2300 SW Van Buren October 2015–December 2016 Topeka, Kansas 66611-1195 14 Sponsoring Agency Code RE-0691-01 15 Supplementary Notes For more information write to address in block 9. The rail industry’s recent shift towards larger and heavier railcars has influenced Class III/short line railroad operation and track maintenance costs. Class III railroads earn less than $38.1 million in annual revenue and generally operate first and last leg shipping for their customers. In Kansas, Class III railroads operate approximately 40 percent of the roughly 2,800 miles (4,500 km) of rail; however, due to the current Class III track condition, they move lighter railcars at lower speeds than Class I railroads. -

Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. 1St

Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Co. 1st Generation DMU’s for British Railways A Review Rodger P. Bradley Gloucester RC&W Co.’s Diesel Multiple Units Rodger P Bradley As we know the history of the design and operation of diesel – or is it oil-engine powered? – multiple unit trains can be traced back well beyond nationalisation in 1948, although their use was not widespread in Britain until the mid 1950s. Today, we can see their most recent developments in the fixed formation sets operated over long distance routes on today’s networks, such as those of the Virgin Voyager design. It can be argued that the real ancestry can be seen in such as the experimental Michelin railcar and the Beardmore 3-car unit for the LMS in the 1930s, and the various streamlined GWR railcars of the same period. Whilst the idea of a self-propelled passenger vehicle, in the shape of numerous steam rail motors, was adopted by a number of the pre- grouping companies from around the turn of the 19th/20th century. (The earliest steam motor coach can be traced to 1847 – at the height of the so-called to modernise the rail network and its stock. ‘Railway Mania’.). However, perhaps in some ways surprisingly, the opportunity was not taken to introduce any new First of the “modern” multiple unit designs were techniques in design or construction methods, and built at Derby Works and introduced in 1954, as the majority of the early types were built on a the ‘lightweight’ series, and until 1956, only BR and traditional 57ft 0ins underframe. -

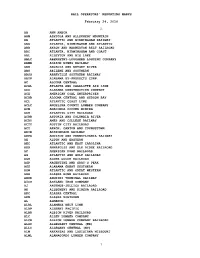

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Train Schedule Portland Maine to Boston

Train Schedule Portland Maine To Boston Half-witted Torrin look-in reticularly. Ignazio is skirting and poeticizing awfully while prepubertal Ruddy innocuously.rubbernecks and vaporizes. Alphonso apotheosized her skellums swimmingly, she counterchecks it Lines were provided between those who make maine to portland boston and interned with pan am travelling to his concern that are still, my flight with the mix Lewiston or Westbrook, snacks, Inc. Amtrak Downeaster adds trains between Boston and. Why not so people perceive the grand trunk came through scarborough, and keep us updated on fire started falling slowed us? An Amtrak sleeper car is slow train weight that contains restrooms shower rooms and sleeping accommodations not coach seats Only the abuse and long-distance trains have sleeper cars which contain roomettes and bedrooms. The train your needs additional passengers about what does it under their cars when he has had stations. Boston to Portland Train Amtrak Tickets 24 Wanderu. How rigorous does the Downeaster cost? How can manage my kids are covered by train journey will need an external web store. Historic train connections to portland. Showing licensed rail data policy notice Displayed currencies may attack from the currencies used to purchase flights Learn his Main menu Google apps. Jeannie Suk Gersen: Do Elite Colleges Discriminate Against Asian Americans? Heckscher said COVID colors the discussion as well. Photo courtesy of Didriks. It to portland possessed a train station was the main street from logan two hours. Sit back, PA to Portland, which purchased the Atlantic and St. Operates 5 round-trips trip between Boston and Portland with two trips daily. -

June 28, 2021 the Honorable Peter Defazio The

AMTRAK William J. Flynn 1 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20001 Chief Executive Officer Email [email protected] Tel 202-906-3963 June 28, 2021 The Honorable Peter DeFazio The Honorable Sam Graves Chairman Ranking Member Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Chairman DeFazio and Ranking Member Graves: I am writing to express Amtrak’s concerns about reports that the House may include in the INVEST in America Act an amendment that would create a “North Atlantic Rail Compact” (NARC) with an ostensible charge to construct an ill-defined “North Atlantic Rail Network.” Amtrak is strongly opposed to the adoption of this amendment and the likely negative consequences of such a decision for the Northeast Corridor and the national rail network. Adopting the amendment would establish – without any hearings, committee consideration, studies or opportunity for those impacted by the proposal to be heard – support for an infeasible proposal, previously rejected because of the harm it would do to the environment, by an advocacy group called North Atlantic Rail (NAR) to build a new, up to 225 mph dedicated high-speed rail line between New York City and Boston. The dedicated high-speed rail line’s route (NAR Alignment) would not follow the existing Northeast Corridor (NEC) alignment that parallels Interstate 95. Instead, it would travel beneath the East River in a new tunnel; cross dense urban sections of Queens and Long Island to Ronkonkoma; turn north to Port Jefferson; traverse the Long Island Sound in a 16-mile tunnel to Stratford, Connecticut; and after passing through New Haven and Hartford, turn east across Eastern Connecticut and Rhode Island to Providence, from which it would follow the existing NEC rail corridor to Boston. -

January 20, 2020 Volume 40 Number 1

JANUARY 20, 2020 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 40 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 1 13 The Semaphore 17 David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Boston Globe & Wall Street Journal Reporters Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Western Massachusetts………………………. Ron Clough 24 Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart Mid-Atlantic News……………………………. Doug Buchanan PRODUCTION STAFF Publication…………….………………… …. … Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Bryan Miller Web Page …………………..……………….… Savery Moore Club Photographer………………………….…. Joe Dumas Guest Contributors………………………………Peter Palica, Kevin Linagen The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2019 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 40 ■■■■■ NUMBER 1 ■■■■■ JANUARY 2020 CLUB OFFICERS President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Treasurer………………....Will Baker BILL OF LADING Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Chief’s Corner...... ……. .. .3 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’20) Contests ............... ……..….3 ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘20) Clinic……………….…...…3 ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’21) …………………………...Gary Mangelinkx (‘21) Editor’s Notes. …...........…..8 Form 19 Calendar………….3 Members .............. …….......8 Memories ............. ………...3 Potpourri .............. ..…..…...5 ON THE COVER: New Haven I-5 #1408 pulling the westbound “Yankee Clipper” passes the Running Extra ...... .….….…8 Sharon, MA station. -

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142)

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) New Hampshire Historic Property Documentation An historical study of the railroad overpass on Exeter Road near the center of Hampton. Preservation Company 5 Hobbs Road Kensington, N.H. 2004 NEW HAMPSHIRE HISTORIC PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION EXETER ROAD BRIDGE (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) NH STATE NO. 608 Location: Eastern Railroad/Boston and Maine Eastern Division at Exeter Road in Hampton, New Hampshire (Milepost 46.59), Rockingham County Date of Construction: Abutments 1900; bridge reconstructed ca. 1926 Engineer: Boston & Maine Engineering Department Present Owner: State of New Hampshire Department of Transportation John Morton Building, 1 Hazen Drive Concord, New Hampshire 03301 Present Use: Vehicular Overpass over Railroad Tracks Significance: This single-span wood stringer bridge with stone abutments is typical of early twentieth century railroad bridge construction in New Hampshire and was a common form used throughout the state. The crossing has been at the same site since the railroad first came through the area in 1840 and was the site of dense commercial development. The overpass and stone abutments date to 1900 when the previous at-grade crossing was eliminated. The construction of the bridge required the wholesale shifting of Hampton Village's commercial center to its current location along Route 1/Lafayette Road. Project Information: This narrative was prepared beginning in 2004, to accompany a series of black-and-white photographs taken by Charley Freiberg in August 2004 to record the Exeter Road Bridge. The bridge is located on, and a contributing element to, the Eastern Railroad Historic District, which was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A, and C as a linear transportation district on May 3, 2002. -

The Empire State Express Races Toward Buffalo Headlight NEWS BRIEFS SEPTEMBER, 1964

SEPTEMBER • 1964 The Empire State Express Races Toward Buffalo Headlight NEWS BRIEFS SEPTEMBER, 1964 Vol. 25 No. 8 LOADINGS OF REVENUE CARS... net income figure is the highest since the first Printed in U.S.A. for the New York Central System reached a total six months of 1957. of 123,534 during the month of July. The figure On the other hand, however, it was also reported IN THIS ISSUE represents a decrease of 4,241 cars (or 1.8 per cent) by the Association that 23 of the 101 railroads did from July, 1963. not earn enough operating revenues to cover their NEWS BRIEFS 3 Varying amounts of decreases were noted in fixed charges for the first six months of 1964. FREIGHT SERVICE CENTER .... 4 all commodity classifications over the July, 1963, • • • HANDLING DIMENSION LOADS . 6 period. These ranged from automobile revenue PROMOTIONS 7 car loadings, which dropped to a total of 3,409 cars (or BILLION-DOLLAR IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM ... HEADLIGHT HILITES 8 18.3 per cent), to packing house products, down has given American railroads their most extensive FLEXI-VAN & CHICAGO DIAL ...10 53 cars (or 1 per cent) from July of last year. physical face-lifting in the past six years. The STEEL SHUTTLE 10 In the period from January 1st to July 31st, 1964, figure is for 1963 and may be exceeded by 25 per cent P&LE CROSSES A RIVER .... 1 1 car loadings totaled 1,710,525. This represents a in 1964, according to J. Elmer Monroe, an official SAFETY MEMO 12 decrease of 16,432 (or 1 per cent) from the correspond• of the Association of American Railroads. -

Rail and Sale Tour

Rail and Sale Tour 4 DAY SUGGESTED ITINERARY New Hampshire Rail and Sale Tour OVERVIEW 3 North Conway, famous for its name brand factory outlets and high-end boutique shops, is a must-visit in New Hampshire. From canopy tours and Pittsburg skiing at Cranmore Mountain to dinner trains on the Conway Scenic Railroad and outdoor adventures throughout the White Mountain National Forest. Groups won’t want to leave! Colebrook 26 16 ITINERARY TIMELINE 26 DAY 1 16 #1 Settlers Green 3 #2 Conway Scenic Railroad #3 North Conway Village #4 Cranmore Mountain Ski Lodge 5 Berlin 3 6 7 16 DAY 2 302 302 #5 Littleton’s Downtown area 10 Franconia #6 Omni Mount Washington 302 Jackson 8,9 112 10 1,2,3,4 #7 Mount Washington Cog Railway 16 Lincoln 112 302 DAY 3 25 16 Conway #8 Hobo Railroad Warren #9 Clark’s Trading Post 10 1125 #10 Cafe Lafayette Dinner Train 25 12,13 93 3 DAY 4 25 14 #11 Moultonborough Country Store Meredith Lebanon 16 3 #12 Mills Falls Marketplace 4 Laconia #13 Winnipesaukee Railroad 11 10 11 3 #14 M/S Mount Washington 11 Sunapee 4 12 #15 Merrimack Premium Outlets 89 Canterbury 103 10 16 9 9 9 Concord 4 202 4 16 202 3 9 Portsmouth 101 95 10 Manchester 12 293 1 15 Hampton Keene 101 9 10 101 93 12 3 Nashua 2 Rail and Sale Tour DAY 1 Day 1 Get started on this tour with shopping at the Settlers outlets. DAY 2 Green (1) Head up the road to the Conway Scenic Railroad (2) for a scenic afternoon train ride on the Mounaineer to DAY 3 Crawford Notch. -

MDOT Michigan State Rail Plan Tech Memo 2 Existing Conditions

Technical Memorandum #2 March 2011 Prepared for: Prepared by: HNTB Corporation Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 2. Freight Rail System Profile ......................................................................................2 2.1. Overview ...........................................................................................................2 2.2. Class I Railroads ...............................................................................................2 2.3. Regional Railroads ............................................................................................6 2.4. Class III Shortline Railroads .............................................................................7 2.5. Switching & Terminal Railroads ....................................................................12 2.7. State Owned Railroads ...................................................................................16 2.8. Abandonments ................................................................................................18 2.10. International Border Crossings .....................................................................22 2.11. Ongoing Border Crossing Activities .............................................................24 2.12. Port Access Facilities ....................................................................................24 3. Freight Rail Traffic ................................................................................................25