In Flanders Fields Program Transcript.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kimball County, Nebraska

Kimball County, Nebraska Kimball Area Tourism Volume 8 WE HOPE YOU HAD A MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAVE A HAPPY NEW YEAR!! HOLIDAY OPEN HOUSE On December 16 th , we enjoyed hosting a Holiday Open House at the Visitor Center. We were thrilled to have Santa & Mrs. Claus take time out of their busy schedule to drop in for a visit. There was a great turn out and the meet and greet with some of the vendors showcased in our gift shop went wonderfully! We have really appreciated all the community support that we have received and we want to thank everyone who came in to join us. And we of course continue to appreciate all the visitors who stop in to see us on their travels. Visitors were able to play for door prizes, visit with the gift shop vendors, and meet Santa and Mrs. Claus at the Holiday Open House NEW YEAR, NEW THINGS IN KIMBALL There are a few items to share from the town of Kimball. The Bakery has new owners! We are happy to welcome Merrycakes into the current bakery building downtown Kimball. They will continue to offer the same wonderful donuts we know and love as well as amazing cookies, cakes and more. Make sure to get in early because they always sell out fast!! The new transit building renovations are well under way and everyone is excited to see how it will look when it is finished! It will be able to house the Kimball County Transit Service vehicles as well as office space and a conference room. -

November 25 1975 CSUSB

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Paw Print (1966-1983) CSUSB Archives 11-25-1975 November 25 1975 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint Recommended Citation CSUSB, "November 25 1975" (1975). Paw Print (1966-1983). Paper 185. http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint/185 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the CSUSB Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paw Print (1966-1983) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Weekly PewPrint, Tuesday, Nov. 25,1»75, page 2 From the editor's desk A word about the ft'ont cover. Many photos have appeared on the pages of each edition of the PawPrint because the old saying says that one picture says one thousand words, or something like that. Anyway one <rf the best (and easiest) ways to fill up a paper is with photos. The photos on the front page are just a few of the many that were taken by PawPrint photographers. This campus is full of interesting people and exciting things to do. These photos reflect the active people on this campus, the ones who are alive and making the most of their earthly existence. The photos were taken by John Whitehair and Keith Legerat. Last edition This is the last edition of the PawPrint for the fall quarter. We had a lot of fun bringing you all the latest campus news each week but with finals almost here, aU the staffers are magicaUy turning back into students who have a lot of studying to catch up on. -

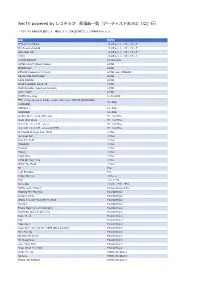

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Big Bang 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour in Seoul Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Bang 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop / Stage & Screen Album: 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul Country: South Korea Released: 2013 Style: Dance-pop, Pop Rap, K-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1304 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1891 mb WMA version RAR size: 1730 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 540 Other Formats: DTS MP4 AAC VOC MOD AIFF AA Tracklist Disc 01 | 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul 1 Tonight 2 Hands Up 3 Fantastic Baby 4 How Gee 5 Stupid Liar 6 High High 7 Strong Baby + 어쩌라고 (What Can I Do) 8 가라가라 고 (Gara Gara Go) 9 Cafe 10 Bad Boy 11 Blue 12 재미없어 (Ain't No Fun) 13 사랑먼지 (Love Dust) 14 Love Song 15 나만 바라봐 (Only Look At Me) + Wedding Dress + Where U At 16 날개 (Wings) 17 하루하루 (Haru Haru) 18 거짓말 (Lies) 19 마지막 인사 (Last Farewell) 20 붉은 노을 (Sunset Glow)(Encore) 21 천국 (Heaven)(Encore) 22 Bad Boy (Double Encore) 23 Fantastic Baby (Double Encore) Disc 02 | Special Features 1 Making Film Multi Angle - Bad Boy (Encore) G-Dragon / T.O.P / Taeyang / Daesung / 2 Seungri Companies, etc. Marketed By – KBS Media Inc. Distributed By – KBS Media Inc. Notes Live DVD footage from BIGBANG's 2012 Alive World Tour Concert at the Olympic Gymnastics Stadium in Seoul on March 2-4, 2012. - 2 DVD - Photobook - First press comes with YG Family Card - Poster Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8803581194524 Other: 2013-KDVD0002 Related Music albums to 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul by Big Bang Big Bang - Bigbang Best Collection (Korea Edition) YG Family - YG Family 2014 World Tour: Power (Concert In Seoul Live CD) Fairport Convention - Encore Encore Various - The Swing Era: Encore! Fairport Convention - Farewell, Farewell Big Bang - 2015 Bigbang World Tour [Made] In Seoul DVD The Platters - More Encore Of Golden Hits Big Bang - Special Edition. -

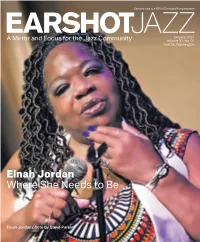

Elnah Jordan Where She Needs to Be

Earshot Jazz is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization January 2021 A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Volume 37, No. 01 Seattle, Washington Elnah Jordan Where She Needs to Be Elnah Jordan photo by Steve Parent Letter from the Director Now Serving Number 21! EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Happy New Year from everyone here at John Gilbreath Earshot Jazz! It almost seems like any MANAGING DIRECTOR glimpses of optimism for the coming year Karen Caropepe should be accompanied by a medal of valor MARKETING & DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATE for making it as far as we have through the Lucienne Aggarwal EARSHOT JAZZ EDITOR battleground of 2020. We hope that you and Lucienne Aggarwal yours are safe and healthy, and are able to EARSHOT JAZZ COPY EDITOR discern at least a glimmer of light at the end Caitlin Carter of this tunnel. CONTRIBUTING WRITERS I believe that we’ve all stepped significantly Ian Gwin, Willem de Koch, Paul Rauch CALENDAR EDITORS outside of our “normal” lives in this past John Gilbreath photo by Bill Uznay Carol Levin and Jane Emerson year, and that may ultimately be a use- PHOTOGRAPHY ful process for many of us. While the global pandemic essentially forced us Daniel Sheehan to pull back into ourselves, the isolation and focus on the essentials of life L AYO U T provided the time and the platform for serious introspection. The killing of Karen Caropepe George Floyd and others at the hands of the police, and the justifiable, even DISTRIBUTION overdue, outrage those killings brought about, was exacerbated by a political Karen Caropepe, Dan Dubie & Earshot Jazz volunteers system that was modeling behaviors that seemed hopelessly self-serving and SEND CALENDAR INFORMATION TO: fundamentally out of touch with the world around us. -

Japanese History in Salinas Chinatown April 29, 2011

National Steinbeck Center Exhibition Japanese History in Salinas Chinatown April 29, 2011 By Robert Danziger; [email protected] Sound Log Playlist: Day 1: The Bonsho Comes to Salinas 0:00 - 0:49 Bonsho 0:29 - 1:40 Japanese Train 1:25 - 1:44 Foghorn 1:52 - 2:23 Asian Kids 1:48 - 2:51 Parade crowd and Buddhist Temple courtyard 2:18 - 2:44 First Striking of the Bell 2:27 - 3:07 Kendo - Ritual Counting 2:58 - 4:53 Gendai ni Ikiru; San Jose Taiko; Rhythm Journey; 2005 4:45 - 5:16 Asian Kids 4:53 – 5:09 Studebaker driving away 4:57 - 5:36 Mochi Making 5:27 - 7:19 Yuyake Koyake (Sunset Glow); Victor Jidou Gasshoudan; 2007 7:15 - 7:27 Light Applause and record player needle drop 7:22 - 8:43 Kawa No Nagare No Youni; Nihonmachi: The Place to Be; Original Cast Recording 8:24 - 8:59 Train passes on the nearby tracks 8:48 - 9:41 Bahay Kubo (YouTube); Images of the Phillipines; 9:35 - 10:05 Kansho sounds people to attend a service in the Temple 9:56 - 10:54 Meciendo; Maria Del Rey; Lullabies of Latin America; 1999 10:33 - 10:51 Sports sequence. Girls and boys basketball, volley ball, kendo, tennis, golf, skeet shooting, baseball, football and other sports are all depicted in family memoirs and pictures. 10:44 – 10:50 Playing Hanafudo, a card game 10:43 - 11:10 Stormy weather runoff, 10:57 - 10:59 Wind chimes in the Temple courtyard 11:07 - 11:10 Baby 11:05 - 12:22 Mido Mountain; Yo-Yo Ma; Essential Yo-Yo Ma; 2004 11:12 - 11:33 Birds of the area Sleeping Time Day 2 -back to work 12:18 - 12:28 Rooster 12:17 - 12:38 Birds 12:21 - 13:50 Plowing Sequence. -

Ismert K-Pop Előadók Dalai 5

Ismert előadók híresebb dalai - 5 Írta: Edina holmes Mi is az a K-pop? VIII. Zene k-pop 094 Ezzel a résszel befejezzük az ismerkedést a k-pop dalokkal az első generációtól mostanáig. A változatosság érdekében nemcsak egy generációt veszünk végig a cikkben, hanem az összesből sze- mezgetünk időrendi sorrendben. Vágjunk is bele! A dalokat meghallgathatjátok az edinaholmes. com-on előadók szerinti lejátszólistákban. Psy Aktív évek: 2001-napjainkig Ügynökség: P Nation Híresebb dalai: Bird, The End, Champion, We Are The One, Delight, Entertainer, Right Now, Shake It, Gangnam Style, Gentleman, Daddy, Napal Baji, New Face, I Luv It Big Bang Sechs Kies Tagok száma: 4 J. Y. Park Tagok száma: 4 Aktív évek: 2006-napjainkig Aktív évek: 1994-napjainkig Aktív évek: 1997-2000; 2016-napjainkig Lee Hyori Ügynökség: YG Ügynökség: JYP Ügynökség: YG Aktív évek: 2003-napjainkig Híresebb dalaik: Lies, Last Farewell, Haru Haru, Híresebb dalai: Don’t Leave Me, Elevator, Híresebb dalaik: School Byeolgok, Ügynökség: Esteem Sunset Glow, Tonight, Love Song, Blue, Bad Boy, She Was Pretty, Honey, Kiss, Your House, Pom Saeng Pom Sa, Chivalry, Road Fighter, Híresebb dalai: 10 Minutes, Toc Toc Toc, Fantastic Baby, Monster, Loser, Bae Bae, Someone Else, You’re The One, Who’s Your Reckless Love, Couple, Com’ Back, Hunch, U-Go-Girl, Swing, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Bang Bang Bang, If You, Let’s Not Fall In Love, Mama?, I’m So Sexy, Fever, When We Disco Three Words, Be Well, Something Special Miss Korea, Bad Girls, Seoul, Black Fxxk It, Last Dance, Flower Road AniMagazin Tartalomjegyzék △ Zene k-pop 095 Legendás K-pop zenék - vol 8. -

Spring 2020 Plant Sale

2020 PLANT CATALOG ONLINE SPRING Presale online shopping begins April 27 at 10 a.m. Member & volunteer online shopping is between April 28 at 10 a.m. and May 1 at 4 p.m. This catalog is not an order form. TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquatics .................................... 1 Container Garden in a Bag .......... 3 Fruits, Berries & Vegetables ........... 4 Grown at the Gardens ................. 7 Herbs ...................................... 14 Houseplants ............................. 15 Plant Select ® ............................ 16 Rock Alpine ............................. 17 Seeds ...................................... 18 Specialty Succulents .................. 20 Summer Bulbs ........................... 21 The Shop at the Gardens ........... 22 Poppy by Sue Carr, 2019, acrylics. Denver Botanic Gardens School of Botanical Art & Illustration. PRESENTING SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSORS 10th & York Street botanicgardens.org AQUATICS PRICE RANGE: $5-$35 | Colorado may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think of aquatic plants, but anyone who has visited the Monet Pool in August knows they can flourish in ponds and water features in this area. You’ll find a wide variety of aquatic plants, some of which were grown on site. * Selections may vary depending on availability. American Frogbit Japanese Iris, Hall of Marble Arrowhead Japanese Iris, Melody Australia Canna Japanese Iris, Sorcerer’s Triumph Aztec Arrowhead Japanese Iris, Violet Bengal Tiger Canna Japanese Primrose Black Coral Taro Lavender Musk Blue Flag Iris Lemon Bacopa Blue -

Tải Truyện Hành Trình Của Yêu Nghiệt Trong Showbiz | Chương 22

Trang đọc truyện online truyenhayhoan.com Hành Trình Của Yêu Nghiệt Trong Showbiz Chương 22 : Chương 23 Chương 22: Ở chung đi, vì tình yêu 001sho_zps38c1be7f.jpg “Tình yêu bắt đầu là ngọt ngào, sau đó thì sao?” – Kim Yoo Jin Thời gian chia ly luôn sẽ đến. Đã đến lúc hai người phải trở về ký túc xá của mình. “Uhey, khi nào thì em có thể chuyển ra? Nghe nói hai chị gái kia của em đều có thể tùy ý chuyển ra ngoài ở rồi.” Ôm Uhey, hai người ở một góc nhỏ đầu đường, khe khẽ nói nhỏ. Kwon Ji Yong hôm nay đặc biệt thích cọ đầu hai bên má Uhey, giống như con mèo lông vàng cầu được âu yếm vậy. “Uhm, có lẽ là tháng sau.” Cô cũng chuẩn bị mua phòng, nhuận bút mấy bài hát khá nhiều, tuy rằng tiền đóng CF..vv.. cô đều đưa về trong nhà, nhưng cái kho tiền nhỏ của mình thì vẫn tích tụ được không ít. Lúc trước vì tuổi nên cô chưa thể tùy tiện mua phòng ra ở riêng, hơn nữa ký túc xá dù sao cũng khiến Uhey có cảm giác ấm áp. Ga Hee và Dam Bi có thời gian sẽ về đó qua đêm, mấy chị em mua đồ ăn vặt tám chuyện đêm cũng rất hài lòng. “Tháng sau? Tháng sau tốt lắm.” Tên Yong nào đó hồi phục lại hơn nữa điểm hp*, đến lúc đó thế nào cũng phải lừa U Bảo đến nhà trọ của mình mới được. -

Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Disease-Like Uveitis Following Nivolumab

Kikuchi et al. BMC Ophthalmology (2020) 20:252 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01519-5 CASE REPORT Open Access Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease-like uveitis following nivolumab administration treated with steroid pulse therapy: a case report Ryo Kikuchi1, Tatsukata Kawagoe1,2* and Kazuki Hotta1 Abstract Background: Immune checkpoint inhibitors can cause various adverse effects. Recently it has been shown that Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) disease-like uveitis can occur in patients treated with nivolumab. Case presentation: A 69-year-old man developed bilateral panuveitis after nivolumab treatment for recurrent hypopharyngeal cancer. Slit lamp examination revealed bilateral granulomatous keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells and partial synechiae. Fundus examination revealed bilateral optic disc edema and diffuse serous retinal detachment. His human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing showed HLA-DRB1*04:05 allele. A lumbar puncture did not demonstrate pleocytosis. Bilateral sub-tenon injections of triamcinolone acetonide were initiated. As his panuveitis did not regress completely, steroid pulse therapy was administered. That therapy led to the resolution of his serous retinal detachment and to rapid improvement in his vision. Following this, we treated him with 50 mg/ day of prednisolone for 1 week and then reduced it by 5 mg every week. No bilateral uveitis relapse had occurred by his 3-month follow-up; however, he subsequently died because of his cancer. Conclusion: To our knowledge, this is the first report of a patient with NVKH who underwent a lumbar puncture. Unlike VKH, our case did not show meningismus or pleocytosis. NVKH may, therefore, have a different etiology from VKH. In cases of NVKH with posterior uveitis, steroid pulse therapy may be considered as a treatment option, as it is in VKH. -

Using War Poetry to Compose Songs

The Studio: online composition resources Resource for teachers: Using war poetry to compose songs Introduction Poetry can be a rich source of inspiration for musical composition. As well as thematic ideas, poetry text can suggest its own rhythms or word painting (music that literally sounds like the words being sung), so is great for young composers as a framework for creative composition. In this project, we are inspired by Magnus Lindberg’s work Triumf att finnas till (Triumph to Exist), premiered by the London Philharmonic Orchestra in November 2018, which uses First World War poetry as its starting point. As this year marks the centenary of the end of the First World War, music director and educator Ros Savournin follows the same brief as Lindberg, and offers a 5-7- session musical composition project for KS3 using First World War poetry as the starting point to create songs. This project, while musical, has great cross-curricular links with history and English. Resources needed: Images of the First World War (at the end of this document) In Flanders Fields words (at the end of this document) Instruments to aid composition: keyboards, percussion, or students’ own instruments Our inspiration: Magnus Lindberg – Triumf att finnas till… (Triumph to Exist, 2018) Magnus Lindberg (1958– ) is a Finnish composer, pianist and conductor. He was the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s Composer-in-Residence from 2014–2017. Commissioned by the LPO, his work Triumf att finnas till… (“Triumph to exist”) honours the centenary of the end of the First World War, and was premiered on 10 November 2018, the eve of Remembrance Sunday. -

Cultivars in the Genus Chaenomeles Claude Weber

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 23 APRIL 5, 1963 NUMBER 3 CULTIVARS IN THE GENUS CHAENOMELES CLAUDE WEBER THE GENUS CHAENOMELES includes the plants commonly known as Japanese or Flowering Quinces, or Japonicas. They are shrubs with bright and showy flowers, blooming normally in the early spring, before the leaves come out, at a time when few other flowers are available in the garden. For this reason, the Flowering Quinces have been popular ever since the first species was introduced to European gardens at the end of the eighteenth century. Before its introduction into Europe, the botanist Thunberg had seen a Flowering Quince growing in Japan. He thought it was a new kind of pear tree, and de- scribed it, in 1784, as Pyrus japonica. A few years later, in 1796, Sir Joseph Banks, director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, introduced the first Japanese Quince into England, assuming it was Thunberg’s species. In 1807, Persoon recognized that because of its numerous seeds this species did not belong to the genus Pyrus, but rather to Cydonia, the common Quince. The plant therefore became known as Cydonia japonica (Thunb.) Pers. In 1822 Lindley established the genus Chaenomeles, distinguishing it from Cydonia primarily by the character of the fruits. Subsequent observations and studies have confirmed Lindley’s opinion, yet some nurserymen still continue to list the species of Chaenomeles under Cydonia. Chaenomeles possesses reniform stipules; short, entire, glandless sepals erect at anthesis; stamens in two rows; completely fused carpels; and styles fused at the base forming a column.