Using War Poetry to Compose Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kimball County, Nebraska

Kimball County, Nebraska Kimball Area Tourism Volume 8 WE HOPE YOU HAD A MERRY CHRISTMAS AND HAVE A HAPPY NEW YEAR!! HOLIDAY OPEN HOUSE On December 16 th , we enjoyed hosting a Holiday Open House at the Visitor Center. We were thrilled to have Santa & Mrs. Claus take time out of their busy schedule to drop in for a visit. There was a great turn out and the meet and greet with some of the vendors showcased in our gift shop went wonderfully! We have really appreciated all the community support that we have received and we want to thank everyone who came in to join us. And we of course continue to appreciate all the visitors who stop in to see us on their travels. Visitors were able to play for door prizes, visit with the gift shop vendors, and meet Santa and Mrs. Claus at the Holiday Open House NEW YEAR, NEW THINGS IN KIMBALL There are a few items to share from the town of Kimball. The Bakery has new owners! We are happy to welcome Merrycakes into the current bakery building downtown Kimball. They will continue to offer the same wonderful donuts we know and love as well as amazing cookies, cakes and more. Make sure to get in early because they always sell out fast!! The new transit building renovations are well under way and everyone is excited to see how it will look when it is finished! It will be able to house the Kimball County Transit Service vehicles as well as office space and a conference room. -

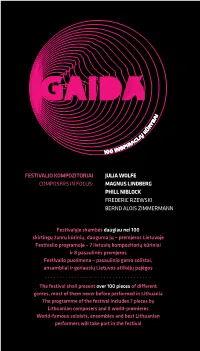

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

(Pdf) Download

ATHANASIOS ZERVAS | BIOGRAPHY BRIEF BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He holds a DM in composition and a MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with Frank Garcia, M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke, and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice “Bunky” Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner. Dr. Athanasios Zervas is an Associate Professor of music theory-music creation at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki Greece, Professor of Saxophone at the Conservatory of Athens, editor for the online theory/composition journal mus-e-journal, and founder of the Athens Saxophone Quartet. COMPLETE BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He has spent most of his career in Chicago and Greece, though his music has been performed around the globe and on dozens of recordings. He is a specialist on pitch-class set theory, contemporary music, composition, orchestration, improvisation, music of the Balkans and Middle East, and traditional Greek music. EDUCATION He holds a DM in composition and an MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen L. Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice ‘Bunky’ Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner; and jazz orchestration/composition with William Russo. RESEARCH + WRITING Dr. -

November 25 1975 CSUSB

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Paw Print (1966-1983) CSUSB Archives 11-25-1975 November 25 1975 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint Recommended Citation CSUSB, "November 25 1975" (1975). Paw Print (1966-1983). Paper 185. http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/pawprint/185 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the CSUSB Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paw Print (1966-1983) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Weekly PewPrint, Tuesday, Nov. 25,1»75, page 2 From the editor's desk A word about the ft'ont cover. Many photos have appeared on the pages of each edition of the PawPrint because the old saying says that one picture says one thousand words, or something like that. Anyway one <rf the best (and easiest) ways to fill up a paper is with photos. The photos on the front page are just a few of the many that were taken by PawPrint photographers. This campus is full of interesting people and exciting things to do. These photos reflect the active people on this campus, the ones who are alive and making the most of their earthly existence. The photos were taken by John Whitehair and Keith Legerat. Last edition This is the last edition of the PawPrint for the fall quarter. We had a lot of fun bringing you all the latest campus news each week but with finals almost here, aU the staffers are magicaUy turning back into students who have a lot of studying to catch up on. -

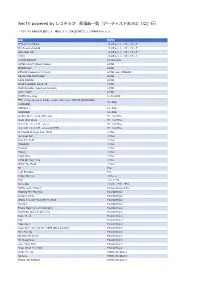

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Symphonic Dances

ADELAIDE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEASON 2019 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Fri 16, 8pm Sat 17, 6.30pm PRESENTING PARTNER Adelaide Town Hall 2 MASTER SERIES 6 Symphonic Dances August Dalia Stasevska Conductor Fri 16, 8pm Louis Lortie Piano Sat 17, 6.30pm Adelaide Town Hall John Adams The Chairman Dances: Foxtrot for Orchestra Ravel Piano Concerto in G Allegramente Adagio assai Presto Louis Lortie Piano Interval Rachmaninov Symphonic Dances, Op.45 Non allegro Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) Lento assai - Allegro vivace Duration Listen Later This concert runs for approximately 1 hour This concert will be recorded for delayed and 50 minutes, including 20 minute interval. broadcast on ABC Classic. You can hear it again at 2pm, 25 Aug, and at 11am, 9 Nov. Classical Conversation One hour prior to Master Series concerts in the Meeting Hall. Join ASO Principal Cello Simon Cobcroft and ASO Double Bassist Belinda Kendall-Smith as they connect the musical worlds of John Adams, Ravel and Rachmaninov. The ASO acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains and all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past, present and future. 3 Vincent Ciccarello Managing Director Good evening and welcome to tonight’s Notwithstanding our concertmaster, concert which marks the ASO debut women are significantly underrepresented of Finnish-Ukrainian conductor, in leadership positions in the orchestra. Dalia Stasevska. Things may be changing but there is still much work to do. Ms Stasevska is one of a growing number of young women conductors Girls and women are finally able to who are making a huge impression consider a career as a professional on the international orchestra scene. -

Big Bang 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour in Seoul Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Bang 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop / Stage & Screen Album: 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul Country: South Korea Released: 2013 Style: Dance-pop, Pop Rap, K-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1304 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1891 mb WMA version RAR size: 1730 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 540 Other Formats: DTS MP4 AAC VOC MOD AIFF AA Tracklist Disc 01 | 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul 1 Tonight 2 Hands Up 3 Fantastic Baby 4 How Gee 5 Stupid Liar 6 High High 7 Strong Baby + 어쩌라고 (What Can I Do) 8 가라가라 고 (Gara Gara Go) 9 Cafe 10 Bad Boy 11 Blue 12 재미없어 (Ain't No Fun) 13 사랑먼지 (Love Dust) 14 Love Song 15 나만 바라봐 (Only Look At Me) + Wedding Dress + Where U At 16 날개 (Wings) 17 하루하루 (Haru Haru) 18 거짓말 (Lies) 19 마지막 인사 (Last Farewell) 20 붉은 노을 (Sunset Glow)(Encore) 21 천국 (Heaven)(Encore) 22 Bad Boy (Double Encore) 23 Fantastic Baby (Double Encore) Disc 02 | Special Features 1 Making Film Multi Angle - Bad Boy (Encore) G-Dragon / T.O.P / Taeyang / Daesung / 2 Seungri Companies, etc. Marketed By – KBS Media Inc. Distributed By – KBS Media Inc. Notes Live DVD footage from BIGBANG's 2012 Alive World Tour Concert at the Olympic Gymnastics Stadium in Seoul on March 2-4, 2012. - 2 DVD - Photobook - First press comes with YG Family Card - Poster Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 8803581194524 Other: 2013-KDVD0002 Related Music albums to 2012 Bigbang Alive Tour In Seoul by Big Bang Big Bang - Bigbang Best Collection (Korea Edition) YG Family - YG Family 2014 World Tour: Power (Concert In Seoul Live CD) Fairport Convention - Encore Encore Various - The Swing Era: Encore! Fairport Convention - Farewell, Farewell Big Bang - 2015 Bigbang World Tour [Made] In Seoul DVD The Platters - More Encore Of Golden Hits Big Bang - Special Edition. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

MAGNUS LINDBERG Accused ∙ Two Episodes

MAGNUS LINDBERG Accused · Two Episodes Anu Komsi Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra Hannu Lintu MAGNUS LINDBERG MAGNUS LINDBERG (1958) Accused (2014) 38:19 Three interrogations for soprano and orchestra 1 Part 1 5:33 2 Part 2 15:35 3 Part 3 17:11 Two Episodes (2016) 17:56 4 Episode 1 9:16 5 Episode 2 8:40 ANU KOMSI, soprano (1–3) FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU, conductor Magnus Lindberg: Two Episodes; Accused Magnus Lindberg’s journey from the edgy modernism of his youthful period in the 1980s to the softer and richer sonorities of his latest works has been long but logical. The changes in his idiom and expression have not been abrupt but are the outcome of gradual musical evolution progressing slowly from one work to the next. Alongside this ongoing stylistic shift, Lindberg’s recent career in the 2010s was outlined by two appointments as composer-in-residence, both spanning multiple seasons, one with the New York Philharmonic (2009– 2012) and the other with the London Philharmonic (2014–2017). Both included commissions for several extensive works. Two Episodes and Accused, featured on the present disc, came about as a result of the London Philharmonic residency and were thus premiered in London. Nevertheless, as is currently common, both works actually had multiple commissioning parties. This reflects the prominent status that Lindberg has attained as a composer and also illustrates that the orchestra is his principal instrument. The co-commissioners of Two Episodes (2016) in addition to the London Philharmonic were BBC Radio 3, the Helsinki Festival and Casa da Música Porto. -

A Stylistic Analysis of Alexander Tcherepnin's Piano Concerto No. 4, Op

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2020 A Stylistic Analysis of Alexander Tcherepnin's Piano Concerto No. 4, Op. 78, With an Emphasis on Eurasian Influences Qin Ouyang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Ouyang, Q.(2020). A Stylistic Analysis of Alexander Tcherepnin's Piano Concerto No. 4, Op. 78, With an Emphasis on Eurasian Influences. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5781 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN 'S PIANO CONCERTO NO. 4, OP. 78, WITH AN EMPHASIS ON EURASIAN INFLUENCES by Qin Ouyang Bachelor of Arts Shanghai Conservatory, 2010 Master of Music California State University, Northridge, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2020 Accepted by: Charles Fugo, Major Professor Phillip Bush, Committee Member Joseph Rackers, Committee Member David Garner, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Qin Ouyang, 2020 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. Charles Fugo, my major professor, for his valuable advice and considerate guidance. A work of this weight would not come to fruition without his patience and encouragement. I extend my thanks to Dr. -

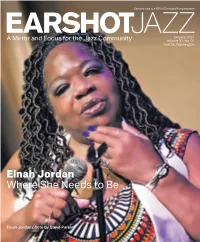

Elnah Jordan Where She Needs to Be

Earshot Jazz is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization January 2021 A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Volume 37, No. 01 Seattle, Washington Elnah Jordan Where She Needs to Be Elnah Jordan photo by Steve Parent Letter from the Director Now Serving Number 21! EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Happy New Year from everyone here at John Gilbreath Earshot Jazz! It almost seems like any MANAGING DIRECTOR glimpses of optimism for the coming year Karen Caropepe should be accompanied by a medal of valor MARKETING & DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATE for making it as far as we have through the Lucienne Aggarwal EARSHOT JAZZ EDITOR battleground of 2020. We hope that you and Lucienne Aggarwal yours are safe and healthy, and are able to EARSHOT JAZZ COPY EDITOR discern at least a glimmer of light at the end Caitlin Carter of this tunnel. CONTRIBUTING WRITERS I believe that we’ve all stepped significantly Ian Gwin, Willem de Koch, Paul Rauch CALENDAR EDITORS outside of our “normal” lives in this past John Gilbreath photo by Bill Uznay Carol Levin and Jane Emerson year, and that may ultimately be a use- PHOTOGRAPHY ful process for many of us. While the global pandemic essentially forced us Daniel Sheehan to pull back into ourselves, the isolation and focus on the essentials of life L AYO U T provided the time and the platform for serious introspection. The killing of Karen Caropepe George Floyd and others at the hands of the police, and the justifiable, even DISTRIBUTION overdue, outrage those killings brought about, was exacerbated by a political Karen Caropepe, Dan Dubie & Earshot Jazz volunteers system that was modeling behaviors that seemed hopelessly self-serving and SEND CALENDAR INFORMATION TO: fundamentally out of touch with the world around us. -

A Summer of Concerts Live on WFMT

A summer of concerts live on WFMT Thomas Wilkins conducts the Grant Park Music Festival from the South Shore Cultural Center Friday, July 29, 6:30 pm Air Check Dear Member, The Guide Greetings! Summer in Chicago is a time to get out and about, and both WTTW and WFMT are out in The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT the community during these warmer months. We’re bringing PBS Kids walk-around character Nature Renée Crown Public Media Center Cat outdoors to engage with kids around the city and suburbs, encouraging them to discover the 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue natural world in their own back yards; and we recently launched a new Chicago Loop app, which you Chicago, Illinois 60625 can download to join Geoffrey Baer and explore our great city and its architectural wonders like never Main Switchboard before. And on musical front, WFMT is proud to bring you live summer (773) 583-5000 concerts from the Ravinia and Grant Park festivals; this month, in a first Member and Viewer Services for the station, we will be bringing you a special Grant Park concert from (773) 509-1111 x 6 the South Shore Cultural Center with the Grant Park Orchestra led by WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 guest conductor Thomas Wilkins. Remember that you can take all of this Chicago Production Center content with you on your phone. Go to iTunes to download the WTTW/ (773) 583-5000 PBS Video app, the new WTTW Chicago’s Loop app, and the WFMT app for Apple and Android.