Donald George Moe-The St. Mark Passion of Reinhard Keiser: a Practical Edition with an Account of Its Historical Background [With] Volume II· Score

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reinhard Keiser (1674-1739) Markuspassion Passion Selon Saint Marc - St Mark Passion

ENSEMBLE JACQUES MODERNE Gli Incogniti - Amandine Beyer Jan Kobow ténor - Thomas e. Bauer basse - Joël Suhubiette direction Jan Kobow ténor (Evangelist) Thomas E. Bauer basse (Jesus) Ensemble Jacques Moderne Anne Magouët soprano (arias et Magd) David Erler alto (arias et Hohepriester) Stephan Van Dyck ténor (arias et Petrus) Guilhem Terrail alto (Judas, Kriegsknecht) Gunther Vandeven alto (Hauptmann) Olivier Coiffet ténor (Pilatus) Cécile Dibon soprano Cyprile Meier soprano Marc Manodritta ténor Didier Chevalier basse Christophe Sam basse Pierre Virly basse Gli Incogniti Amandine Beyer violon 1 Alba Roca violon 2 Marta Páramo alto 1 Ottavia Rausa alto 2 Francesco Romano théorbe Marco Ceccato violoncelle Baldomero Barciela violone Anna Fontana orgue et clavecin Mélodie Michel basson Antoine Torunczyk hautbois Joël Suhubiette direction TRACKS 2 PLAGES CD REINHARD KEISER (1674-1739) Markuspassion Passion selon Saint Marc - St Mark Passion De récentes recherches musicologiques permettent de penser que la « Markuspassion » n’est pas l’œuvre de Reinhard Keiser, essentiellement pour des raisons stylistiques. En revanche, l’attribution à un autre compositeur du XVIIème siècle tel que Nicolaus Bruhns ou Gottfried Keiser, le père de Reinhard Keiser, n’est pas encore avérée et cette question reste donc à ce jour non élucidée. Recent musicological research tends to suggest that the Markuspassion is not the work of Reinhard Keiser, essentially for stylistic reasons. However, it has not yet proved possible to attribute it positively to any other contemporary composer, such as Nicolaus Bruhns, or to Gottfried Keiser, Reinhard’s father, and so its paternity is currently uncertain. Die Ergebnisse jüngster musikwissenschaftlicher Forschungen lassen, vor allem aus stilistischen Gründen, durchaus vermuten, dass Reinhard Keiser nicht der wirkliche Urheber der „Markuspassion“ ist. -

Christoph Graupner

QUANTZ COLLEGIUM ~ CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER · VIOLA CONCERTO IN D MAJOR, GWV 314 CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER (1683-1760) CONCERTO IN D-DUR, GWV 314 FÜR VIOLA, ZWEI VIOLINEN, VIOLA UND BASSO CONTINUO SOLISTIN: AGATA ZIEBA (VIOLA) I. VIVACE ~ II. ADAGIO ~ III. VIVACE Das Schloss Favorite bei Rastatt ist das älteste und einzige nahezu unverändert erhalten gebliebene „Porzel- lanschloss“ Deutschlands. Seine Ausstattung und seine reichhaltigen Sammlungen machen es zu einem Ge- samtkunstwerk von europäischer Bedeutung. Vor über 300 Jahren erbaut unter Markgräfin Sibylla Augusta von Baden-Baden (1675-1733) nach Plänen des Hofbaumeisters Michael Ludwig Rohrer, beherbergen die prächtig ausgestatteten Räume wie einst zu Zeiten der Markgräfin deren kostbare Porzellan-, Fayence- und Glassamm- lung. Das Schloss mit seinem idyllischen Landschaftsgarten war ein Ort der Feste und der Jagd. Markgräfin Sibylla Augusta und ihr Sohn Ludwig Georg fanden hier Erholung abseits des strengeren höfischen Zeremoni- ells in der Rastatter Residenz. Die Ausstattung birgt eine verschwenderische Fülle spätbarocker Dekorationen und viele ungewöhnliche Details. Zentrum des „Lustschlosses“ ist, wie in fast jedem barocken Schloss, die „Sala Terrena“, der Gartensaal, der für Feierlichkeiten diente und in dem auch dieses Konzert stattfand. In Schloss Favorite Rastatt fand man da- für eine ungewöhnliche Form. Der achteckige Saal im Erdgeschoss mit seinen vier Wasserbecken und Brun- nenfiguren, die die vier Jahreszeiten darstellen, öffnet sich nach oben bis zur Kuppel. Seine Wände sind mit blau-weißen Fayence-Fliesen belegt, die sich im ganzen Gebäude wiederfinden. Das Schloss und sein Garten sind eines von 60 historischen Monumenten im deutschen Südwesten. Die Staatli- chen Schlösser und Gärten Baden-Württemberg öffnen, vermitteln, entwickeln und bewahren diese landeseige- nen historischen Monumente mit dem Anspruch, das kulturelle Erbe in seiner Authentizität zu bewahren, es mit Leben zu fül- len und es für zukünftige Generationen zu erhalten. -

Document Cover Page

A Conductor’s Guide and a New Edition of Christoph Graupner's Wo Gehet Jesus Hin?, GWV 1119/39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Seal, Kevin Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 06:03:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645781 A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN?, GWV 1119/39 by Kevin M. Seal __________________________ Copyright © Kevin M. Seal 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by: Kevin Michael Seal titled: A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN, GWV 1119/39 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 3, 2020 John T Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Rex A. Woods Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

BMC 13 - Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767): Orchestral Music

BMC 13 - Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767): Orchestral Music Born in Magdeburg in 1681, Telemann belonged to a family that had long been connected with the Lutheran Church. His father was a clergyman, his mother the daughter of a clergyman, and his elder brother also took orders, a path that he too might have followed had it not been for his exceptional musical ability. As a child he showed considerable musical talent, mastering the violin, flute, zither and keyboard by the age of ten and composing an opera (Sigismundus) two years later to the consternation of his family (particularly his mother's side), who disapproved of music. However, such resistance only reinforced his determination to persevere in his studies through transcription, and modeling his works on those of such composers as Steffani, Rosenmüller, Corelli and Antonio Caldara. After preparatory studies at the Hildesheim Gymnasium, he matriculated in Law (at his mother's insistence) at Leipzig University in 1701. That he had little intention of putting aside his interest in music is evident from his stop at Halle, en route to Leipzig, in order to make the acquaintance of the young Handel, with whom he was to maintain a lifelong friendship. It was while he was a student at Leipzig University that a career in music became inevitable. At first it was intended that he should study language and science, but he was already so capable a musician that within a year of his arrival he founded the student Collegium Musicum with which he gave public concerts (and which Bach was later to direct), wrote operatic works for the Leipzig Theater; in 1703 he became musical director of the Leipzig Opera, and was appointed Organist at the Neue Kirche in 1704. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT SWR2 Musikstunde Ein Opernhaus für eine Stadt - Die Hamburger Gänsemarkt - Bühne 1678 – 1738 Folge II: Reinhard Keiser oder: Oper als politischer Kommentar Mit Sylvia Roth Sendung: 19. September 2017 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2017 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Musikstunde können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde mit Sylvia Roth 18. September - 22. September 2017 Ein Opernhaus für eine Stadt - Die Hamburger Gänsemarkt - Bühne 1678 – 1738 Folge II: Reinhard Keiser oder: Oper als politischer Kommentar Signet Einen wunderschönen guten Morgen von Sylvia Roth. Ich begrüße Sie zur zweiten Folge unserer Woche über die Hamburger Oper am Gänsemarkt – heute widmen wir uns unter anderem Reinhard Keiser und den politischen Inhalten seiner Werke. Musik 1: Johann Sigismund Kusser: Fanfare aus der Suite Nr. 4 in C-Dur (1'07) Aura musicale Leitung: Balász Mate M0340419 003 Hamburg, 1702. Zwischen St. Nicolai und St. Katharinen stochert Piet, der Fleetenkieker, den Müll aus dem Fleet. Dass Hamburg wegen seiner vielen kleinen Wasserkanäle, den Fleeten, gerne mit Venedig verglichen wird, ist ja schön und gut – aber was da alles an Müll zum Vorschein kommt, sobald bei Ebbe der Wasserspiegel sinkt! N Haufen Schiet .. -

"Mixed Taste," Cosmopolitanism, and Intertextuality in Georg Philipp

“MIXED TASTE,” COSMOPOLITANISM, AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN’S OPERA ORPHEUS Robert A. Rue A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2017 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig Gregory Decker © 2017 Robert A. Rue All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor Musicologists have been debating the concept of European national music styles in the Baroque period for nearly 300 years. But what precisely constitutes these so-called French, Italian, and German “tastes”? Furthermore, how do contemporary sources confront this issue and how do they delineate these musical constructs? In his Music for a Mixed Taste (2008), Steven Zohn achieves success in identifying musical tastes in some of Georg Phillip Telemann’s instrumental music. However, instrumental music comprises only a portion of Telemann’s musical output. My thesis follows Zohn’s work by identifying these same national styles in opera: namely, Telemann’s Orpheus (Hamburg, 1726), in which the composer sets French, Italian, and German texts to music. I argue that though identifying the interrelation between elements of musical style and the use of specific languages, we will have a better understanding of what Telemann and his contemporaries thought of as national tastes. I will begin my examination by identifying some of the issues surrounding a selection of contemporary treatises, in order explicate the problems and benefits of their use. These sources include Johann Joachim Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte zu spielen (1752), two of Telemann’s autobiographies (1718 and 1740), and Johann Adolf Scheibe’s Critischer Musikus (1737). -

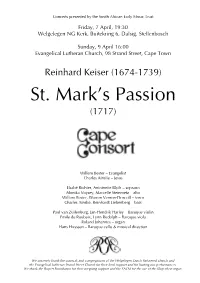

Reinhard Keiser, St Mark's Passion

Concerts presented by the South African Early Music Trust Friday, 7 April, 19:30 Welgelegen NG Kerk, Buitekring 6, Dalsig, Stellenbosch Sunday, 9 April 16:00 Evangelical Lutheran Church, 98 Strand Street, Cape Town Reinhard Keiser (1674-1739) St. Mark’s Passion (1717) Willem Bester – Evangelist Charles Ainslie – Jesus Elsabé Richter, Antoinette Blyth – soprano Monika Voysey, Marcelle Steinmetz – alto Willem Bester, Warren Vernon-Driscoll – tenor Charles Ainslie, Reinhardt Liebenberg – bass Paul van Zuilenburg, Jan-Hendrik Harley – Baroque violin Emile de Roubaix, Lynn Rudolph – Baroque viola Roland Johannes – organ Hans Huyssen – Baroque cello & musical direction We sincerely thank the councils and congregations of the Welgelegen Dutch Reformed church and the Evangelical Lutheran Strand Street Church for their kind support and for hosting our performances. We thank the Rupert Foundation for their on-going support and the SACM for the use of the Klop chest organ. Programme Notes Much speculation surrounds the life of the German Baroque composer Reinhard Keiser. Schooled at the famous Thomasschule in Leipzig, where he studied with Schelle and Kuhnau, he rose to fame as a highly prolific and extremely popular opera composer. After a short sojourn in Braunschweig he worked mainly in Hamburg and – together with Telemann and Händel – made a considerable contribution to the city’s reputation as Germany’s prime operatic centre during the early 18th century. It was only in 1728, after many failed attempts to attain a permanent tenure that, at the age of 54, he was finally appointed cantor of Hamburg’s cathedral – as successor to his friend Johann Mattheson. In stark contrast to his current obscurity, Keiser’s contemporaries eulogized about his proficiency and inventiveness, the spontaneity and naturalness of his melodies, as well as the dramatic and rhetorical effect of his instrumentations. -

Graupner US 11/6/08 10:03 Page 4

570459 bk Graupner US 11/6/08 10:03 Page 4 Also available: Johann Christoph GRAUPNER Partitas for Harpsichord 8.557884 8.570335 Partita in A major Partita in C minor Partita in F minor Get this free download from Classicsonline! Fischer: Euterpe (Suite No. 6): Chaconne (‘Winter’) Copy this Promotion Code NaxZWO8e52fI and go to http://www.classicsonline.com/mpkey/fis36_main. Downloading Instructions Chaconne in A major 1 Log on to Classicsonline. If you do not have a Classicsonline account yet, please register at http://www.classicsonline.com/UserLogIn/SignUp.aspx. 2 Enter the Promotion Code mentioned above. 3 On the next screen, click on “Add to My Downloads”. Naoko Akutagawa 8.570459 4 570459 bk Graupner US 11/6/08 10:03 Page 2 Johann Christoph Graupner (1683-1760) nearly contemporaries and barely out of their teens, en rondeau element of an opening “theme” repeated in Partitas for Harpsichord duelling at the harpsichord in the orchestra pit of the the middle and at the end) comes at the end of one of the Hamburg opera after a frustrating rehearsal. longest of the partitas, which already has two of In 1722 the town council of Leipzig was searching for a and performance of large-scale vocal and orchestral Graupner’s partitas are stylistically more advanced Graupner’s favoured final movements: a set of new cantor for the church of St Thomas. They first works, the great mass of which (including 1442 than Handel’s, simply because they were in all variations and a gigue. To add the chaconne would accepted the application of the most famous musician in cantatas) are only now being catalogued. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 Musikstunde Ein Opernhaus für eine Stadt – Die Hamburger Gänsemarktoper 1678 – 1738 (5) Von Sylvia Roth Sendung: 14. Februar 2020 9.05 Uhr Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2017 SWR2 können Sie auch im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de und auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App hören – oder als Podcast nachhören: Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de Die SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen mindestens sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app SWR2 Musikstunde mit Sylvia Roth 10. Februar 2020 – 14. Februar 2020 Ein Opernhaus für eine Stadt – Die Hamburger Gänsemarktoper 1678 – 1738 Folge V: Das Ende Einen wunderschönen guten Morgen zur letzten Folge unserer Hamburger Woche über die Gänsemarktoper. Dazu begrüßt sie Sylvia Roth. Schön, dass Sie wieder dabei sind! Georg Friedrich Händel: Rodrigo, Gigue The Parley of Instruments, Leitung: Peter Holman Titel CD: Händel in Hamburg, Music from Almira, Daphne, Nero, Florindo, Hyperion, CDH55324, LC 9451 M0322252 030 Hamburg, 1733. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT SWR2 Musikstunde „Georg Philipp Telemann - eine musikalische Begegnung“ (1-5) V. „...da ich in voller Arbeit sitze“ - Musikdirektor in Hamburg Mit Antonie von Schönfeld Sendung: 23. Juni 2017 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2017 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Musikstunde können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde mit Antonie von Schönfeld 19. Juni – 23. Juni 2017 „Georg Philipp Telemann - eine musikalische Begegnung“ (1-5) V. „...da ich in voller Arbeit sitze“ - Musikdirektor in Hamburg Signet und zu diesem letzten Abschnitt unserer Lebensreise mit diesem vielseitigen Barockkomponisten, dessen Todestag sich am kommenden Sonntag zum 250. Mal jährt, begrüßt Sie - AvS Im Herbst des Jahres 1721 tritt Georg Philipp Telemann in Hamburg seine Stelle als Musikdirektor der fünf Hauptkirchen und Kantor am Johanneum an. Als er einige Jahre später, 1728, den ersten Teil des „Getreuen Music-Meisters“ -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 Musikstunde Ein Opernhaus für eine Stadt – Die Hamburger Gänsemarktoper 1678 – 1738 (4) Von Sylvia Roth Sendung: 13. Februar 2020 9.05 Uhr Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2017 SWR2 können Sie auch im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de und auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App hören – oder als Podcast nachhören: Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de Die SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen mindestens sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app SWR2 Musikstunde mit Sylvia Roth 10. Februar 2020 – 14. Februar 2020 Ein Opernhaus für eine Stadt – Die Hamburger Gänsemarktoper 1678 – 1738 Folge IV: Georg Philipp Telemann oder: Oper als Repräsentation Mit Sylvia Roth und der Hamburger Oper am Gänsemarkt, guten Morgen! Heute steht nicht nur Georg Philipp Telemann im Zentrum des Interesses, sondern auch das repräsentative Gesicht des frühen Opernhauses an der Alster. Georg Philipp Telemann: „Der neumodische Liebhaber Damon“, Tanz der Faune (0'58) La Stagione Frankfurt, Leitung: Michael Schneider CD: Telemann, Damon, WDR / Deutschlandradio / cpo 999 429-2, LC 8492 Hamburg, 1722. -

Johann David Heinichen: Hidden Genius of the Baroque by Andrew Hartman

Johann David Heinichen: Hidden Genius of the Baroque by Andrew Hartman The Baroque Era The history of classical music is typically divided into several major periods. The Baroque era, generally classified as between 1600 -1750, is of critical importance for several reasons. It was the first era to introduce large-scale instrumental forces into classical music. Prior to the Baroque era, most music was either for unaccompanied voices, chorus and organ, or instrumental music using a single instrument, such as the organ, lute or harpsichord. In the Baroque era for the first time massed instrumental forces were both joined with choral forces, and exhibited independently. In the Medieval and Renaissance eras the venues where music was performed were mainly limited to houses of worship, or court settings under royal patronage. The rise of an infrastructure and audience for instrumental music outside the church or the drawing rooms of kings and queens had to wait for the Baroque era. Likewise for the performance of opera. First in Italy, where composers such as Cavalli thrilled audiences during Venetian Carnival, and later with Handel’s opera company in London, a widespread audience for operatic music outside of court settings began in the Baroque. Obviously this change did not happen overnight, and overlapped with the old model of royal and aristocratic patronage. One need only mention Haydn at Esterhazy to demonstrate the staying power of the older model. Yet it was the Baroque era that gave rise to these important changes in the way classical music was created and consumed by the public. Additionally, it was in the Baroque era that for the first time a body of masterpieces was composed that would outlast their creators with a mass public.