Linguistics and Ethnology Against Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gordon Ramsay Uncharted

SPECIAL PROMOTION SIX DESTINATIONS ONE CHEF “This stuff deserves to sit on the best tables of the world.” – GORDON RAMSAY; CHEF, STUDENT AND EXPLORER SPECIAL PROMOTION THIS MAGAZINE WAS PRODUCED BY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL IN PROMOTION OF THE SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: CONTENTS UNCHARTED PREMIERES SUNDAY JULY 21 10/9c FEATURE EMBARK EXPLORE WHERE IN 10THE WORLD is Gordon Ramsay cooking tonight? 18 UNCHARTED TRAVEL BITES We’ve collected travel stories and recipes LAOS inspired by Gordon’s (L to R) Yuta, Gordon culinary journey so that and Mr. Ten take you can embark on a spin on Mr. Ten’s your own. Bon appetit! souped-up ride. TRAVEL SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: ALASKA Discover 10 Secrets of UNCHARTED Glacial ice harvester Machu Picchu In his new series, Michelle Costello Gordon Ramsay mixes a Manhattan 10 Reasons to travels to six global with Gordon using ice Visit New Zealand destinations to learn they’ve just harvested from the locals. In from Tracy Arm Fjord 4THE PATH TO Go Inside the Labyrin- New Zealand, Peru, in Alaska. UNCHARTED thine Medina of Fez Morocco, Laos, Hawaii A rare look at Gordon and Alaska, he explores Ramsay as you’ve never Road Trip: Maui the culture, traditions seen him before. and cuisine the way See the Rich Spiritual and only he can — with PHOTOS LEFT TO RIGHT: ERNESTO BENAVIDES, Cultural Traditions of Laos some heart-pumping JON KROLL, MARK JOHNSON, adventure on the side. MARK EDWARD HARRIS Discover the DESIGN BY: Best of Anchorage MARY DUNNINGTON 2 GORDON RAMSAY: UNCHARTED SPECIAL PROMOTION 3 BY JILL K. -

Kapampangan Language Endangerment Through Lexical

Kapampangan Lexical Borrowing from Tagalog: Endangerment rather than Enrichment Michael Raymon M. Pangilinan [email protected] Abstract It has sometimes been argued that the Kapampangan language will not be endangered by lexical borrowings from other languages and that lexical borrowings help enrich a language rather than endanger it. This paper aims to prove otherwise. Rather than being enriched, the socio-politically dominant Tagalog language has been replacing many indigenous words in the Kapampangan language in everyday communication. A number of everyday words that have been in use 20 years ago ~ bígâ (clouds), sangkan (reason), bungsul (to faint) and talágâ (artesian well) just to name a few ~ have all been replaced by Tagalog loan words and are no longer understood by most young people. This paper would present a list of all the words that have been replaced by Tagalog, and push the issue that lexical borrowing from a dominant language leads to endangerment rather than enrichment. I. Introduction At first glance, the Kapampangan language does not seem to be endangered. It is one of the eight major languages of the Philippines with approximately 2 million speakers (National Census and Statistics Office, 2003). It is spoken by the majority in the province of Pampanga, the southern half of the province of Tarlac, the northeast quarter of the province of Bataan, and the bordering communities of the provinces of Bulacan and Nueva Ecija (Fig. 1). It has an established literature, with its grammar being studied as early as 1580 by the Spanish colonisers (Manlapaz, 1981). It has also recently penetrated the electronic media: the first ever province-wide news in the Kapampangan language was televised in 2007 by the Pampanga branch of the Manila-based ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation. -

Learning to Build a Wood Fired Earth Oven

Learning To Build A Wood Fired Earth Oven Dedicated to all lovers of planet Earth 1 | P a g e www.apieceofrainbow.com 3 weeks ago I attended an earth oven building class taught by one of the best teachers in this field, Kiko Denzer, at the fabulous Grain Gathering. Kiko and the event organizers graciously allowed me to share my amazing class experience. This article is not meant to be used as a building manual. If you are planning to build one, make sure to check out the indispensable resources here http://www.apieceofrainbow.com/build-a-wood- fired-earth-oven/#Helpful-Resources as well as safety and local building codes. During the 6 hour long class, we built 2 portable earth ovens, which were auctioned the next day. I learned so much about building with earth and other readily available materials. There's such simplicity and beauty to the process that I find deeply inspiring. The wood fired earth ovens(aka- cob ovens) are easy to build, and can give 12 hours of cooking after each firing, to make super delicious goodies from pizzas, bread, cookies to casseroles. 2 | P a g e www.apieceofrainbow.com Above is a top section of an earth oven. Materials, Design and Foundation The ovens we made measure about 24" in finished diameter, and have an inside cooking area of 12" diameter by 14" high. They each weigh about 250 lbs, and each took about two 5-gallon buckets of clay and sand mixture to build. If you want a larger oven, please adjust the materials accordingly. -

Development, Implementation and Testing of Language Identification System for Seven Philippine Languages

Philippine Journal of Science 144 (1): 81-89, June 2015 ISSN 0031 - 7683 Date Received: ?? ???? 2014 Development, Implementation and Testing of Language Identification System for Seven Philippine Languages Ann Franchesca B. Laguna1 and Rowena Cristina L. Guevara2 1Computer Technology Department, College of Computer Studies, De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila 2Electrical and Electronics Engineering Institute, University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City Three Language Identification (LID)approaches, namely, acoustic, phonotactic, and prosodic approaches are explored for Philippine Languages. Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) is used for acoustic and prosodic approaches. The acoustic features used were Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC), Perceptual Linear Prediction (PLP), Shifted Delta Cepstra (SDC) and Linear Prediction Cepstral Coefficients (LPCC). Pitch, rhythm, and energy are used as prosodic features. A Phone Recognition followed by Language Modelling (PRLM) and Parallel Phone Recognition followed by Language Modelling (PPRLM) are used for the phonotactic approach. After establishing that acoustic approach using a 32nd order PLP GMM-EM achieved the best performanceamong the combinations of approach and feature, three LID systems were built: 7-language LID,pair-wise LID and hierarchical LID; with average accuracy of 48.07%, 72.64% and 53.99%, respectively. Among the pair-wise LID systems the highest accuracy is 92.23% for Tagalog and Hiligaynon and the lowest accuracy is 52.21% for Bicolano and Tausug. In the hierarchical LID system, the accuracy for Tagalog, Cebuano, Bicolano, and Hiligaynon reached 80.56%, 80.26%, 78.26%, and 60.87% respectively. The LID systems that were designed, implemented and tested, are best suited for language verification or for language identification systems with small number of target languages that are closely related such as Philippine languages. -

Wege Zur Musik

The beginnings 40,000 years ago Homo sapiens journeyed up the River Danube in small groups. On the southern edge of the Swabian Alb, in the tundra north of the glacial Alpine foothills, the fami- lies found good living conditions: a wide offering of edible berries, roots and herbs as well as herds of reindeer and wild horses. In the valleys along the rivers they found karst caves which offered protection in the long and bleak winters. Here they made figures of animals and hu-mans, ornaments of pearls and musical instruments. The archaeological finds in some of these caves are so significant that the sites were declared by UNESCO in 2017 as ‘World Heritage Sites of Earliest Ice-age Art’. Since 1993 I have been performing concerts in such caves on archaic musical instruments. Since 2002 I have been joined by the percussion group ‘Banda Maracatu’. Ever since prehis- toric times flutes and drums have formed a perfect musical partnership. It was therefore natu- ral to invite along Gabriele Dalferth who not only made all of the ice-age flutes used in this recording but also masters them. The archaeology of music When looking back on the history of mankind, the period over which music has been docu- mented is a mere flash in time. Prior to that the nature of music was such that once it had fainted away it had disappeared forever. That is the situation for music archaeologists: The music of ice-age hunters and gatherers has gone for all time and cannot be rediscovered. Some musical instruments however have survived for a long time. -

A Multidisciplinary Study of a Burnt and Mutilated Assemblage of Human Remains from a Deserted Mediaeval Village in England

JASREP-00837; No of Pages 15 Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports xxx (2017) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep A multidisciplinary study of a burnt and mutilated assemblage of human remains from a deserted Mediaeval village in England S. Mays a,b,c,⁎, R. Fryer b, A.W.G. Pike b, M.J. Cooper d,P.Marshalla a Research Department, Historic England, United Kingdom b Archaeology Department, University of Southampton, UK c School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, UK d Ocean and Earth Science, National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton, UK article info abstract Article history: This work is a study of an assemblage of disarticulated human skeletal remains from a pit on the Mediaeval village Received 30 November 2016 site of Wharram Percy, England. The remains show evidence of perimortal breakage, burning and tool marks. The Received in revised form 13 February 2017 purpose of the study is to attempt to shed light on the human activity that might have produced the assemblage. Accepted 20 February 2017 The remains are subject to radiocarbon dating, strontium isotope analysis, and gross and microscopic osteological Available online xxxx examination. The assemblage comprises 137 bones representing the substantially incomplete remains of a min- imum of ten individuals, ranging in age from 2‐4yrstoN50 yrs at death. Both sexes are represented. Seventeen Keywords: fi Radiocarbon bones show a total of 76 perimortem sharp-force marks (mainly knife-marks); these marks are con ned to the Strontium isotope upper body parts. -

Australian Archaeology (AA) Editorial Board Meeting the AA Editorial Board Meeting Will Be Held on Thursday 7 December from 1.00 - 2.00Pm in Hopetoun Room on Level 1

CONFERENCE PROGRAM 6 - 8 December, Melbourne, Victoria Hosted by © Australian Archaeological Association Inc. Published by the Australian Archaeological Association Inc. ISBN: 978-0-646-98156-7 Printed by Conference Online. Citation details: J. Garvey, G. Roberts, C. Spry and J. Jerbic (eds) 2017 Island to Inland: Connections Across Land and Sea: Conference Handbook. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Archaeological Association Inc. Contents Contents Welcome 4 Conference Organising Committee 5 Volunteers 5 Sponsors 6 Getting Around Melbourne 8 Conference Information 10 Venue Floor Plan 11 Instructions for Session Convenors 12 Instructions for Presenters 12 Instructions for Poster Presenters 12 Social Media Guide 13 Meetings 15 Social Functions 16 Post Conference Tours 17 Photo Competition 19 Awards and Prizes 20 Plenary Sessions 23 Concurrent Sessions 24 Poster Presentations 36 Program Summary 38 Detailed Program 41 Abstracts 51 Welcome Welcome We welcome you to the city of Melbourne for the 2017 Australian Archaeological Association Conference being hosted by La Trobe University, coinciding with its 50th Anniversary. We respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the Kulin Nation, a place now known by its European name of Melbourne. We pay respect to their Elders past and present, and all members of the community. Melbourne has always been an important meeting place. For thousands of years, the Wurundjeri, Boonwurrung, Taungurong, Dja Dja Wurrung and the Wathaurung people, who make up the Kulin Nation, met in this area for cultural events and activities. Our Conference theme: ‘Island to Inland: Connections Across Land and Sea’ was chosen to reflect the journey of the First Australians through Wallacea to Sahul. Since then, people have successfully adapted to life in the varied landscapes and environments that exist between the outer islands and arid interior. -

When Did Humans Learn to Boil?

When Did Humans Learn to Boil? JOHN D. SPETH Department of Anthropology, 101 West Hall, 1085 South University Avenue, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1107, USA; [email protected] submitted: 5 September 2014; accepted 4 April 2015 ABSTRACT The control of fire and the beginning of cooking were important developments in the evolution of human food- ways. The cooking techniques available to our ancestors for much of the Pleistocene would have been limited to simple heating and roasting. The next significant change in culinary technology came much later, when humans learned to wet-cook (i.e., “boil,” sensu lato), a suite of techniques that greatly increased the digestibility and nu- tritional worth of foods. Most archaeologists assume that boiling in perishable containers cannot pre-date the appearance of fire-cracked rock (FCR), thus placing its origin within the Upper Paleolithic (UP) and linking it to a long list of innovations thought to have been introduced by behaviorally modern humans. This paper has two principal goals. The first is to alert archaeologists and others to the fact that one can easily and effectively boil in perishable containers made of bark, hide, leaves, even paper and plastic, placed directly on the fire and without using heated stones. Thus, wet-cooking very likely pre-dates the advent of stone-boiling, the latter probably rep- resenting the intensification of an already existing technology. The second goal is to suggest that foragers might have begun stone-boiling if they had to increase the volume of foods cooked each day, for example, in response to larger average commensal-unit sizes. -

Brittany & Its Byways by Fanny Bury Palliser

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Brittany & Its Byways by Fanny Bury Palliser This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.guten- berg.org/license Title: Brittany & Its Byways Author: Fanny Bury Palliser Release Date: November 9, 2007 [Ebook 22700] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BRITTANY & ITS BYWAYS*** Brittany & Its Byways by Fanny Bury Palliser Edition 02 , (November 9, 2007) [I] BRITTANY & ITS BYWAYS SOME ACCOUNT OF ITS INHABITANTS AND ITS ANTIQUITIES; DURING A RESIDENCE IN THAT COUNTRY. BY MRS. BURY PALLISER WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS London 1869 Contents Contents. 1 List of Illustrations. 7 Britanny and Its Byways. 11 Some Useful Dates in the History of Brittany. 239 Chronological Table of the Dukes of Brittany. 241 Index. 243 Transcribers' Notes . 255 [III] Contents. CHERBOURG—Mont du Roule—Visit of Queen Victoria—Har- bour, 1—Breakwater—Dock-Yard, 2—Chantereyne—Hôpi- tal de la Marine, 3—Castle—Statue of Napoleon I.—Li- brary—Church of La Trinité, 4—Environs—Octeville, 5—Lace- school of the Sœurs de la Providence, 11. QUERQUEVILLE—Church of St. Germain, 5—Château of the Comte de Tocqueville, 6. TOURLAVILLE—Château, 7—Crêpes, 11. MARTINVAST—Château, 12. BRICQUEBEC—Castle—History, 12—Valognes, 14. ST.SAUVEUR-le-Vicomte—Demesne—History, 15—Cas- tle—Convent—Abbey, 16. PÉRI- ERS, 17—La Haye-du-Puits, 17—Abbey of Lessay—Mode of Washing—Inn-signs, 18—Church, 19. -

Earth (Fiji) Oven

Earth (Fiji) Oven The Activity: Build a Earth oven on an activity or camp Activity Type: Roles: Patrol Activity Activity Leaders Troop Activity Quartermasters Cooks The Crean Award: Discovery: Terra Nova: Patrol Activity Task/Role in Patrol Skills Patrol Activity Skills Endurance: Polar: Planning Patrol Activity Develop Teamwork Skills SPICES Physical Intellectual Plan Introduction This method of backwoods cooking is a great Patrol activity that requires patience and teamwork. It is a slow burning oven used by native people in the Fiji Islands. It is best suited to sandy soil conditions but will work anywhere. Fire lighting and cooking skills are required. Food will need to be prepared A shovel will also be required to dig the pit for the fire. You will need:- • Selection of food to be cooked – beef or fish, vegetables • Tinfoil • Cabbage leaves • Saw for cutting fire wood • Shovel for digging pit Do Step One Dig a pit about 1.5ft deep and 1ft x 1ft wide and line the bottom with stones. Step Two Light a fire inside pit let it burn for about 30 minutes. Step Three Cover the fire with a thin layer of earth. Step Four Place meat wrapped in tin foil or cabbage leaves on the thin layer of earth. Do Step Five Fill in the rest of the pit with earth. Step Six Light a second fire on top of the pit. Let it burn for about 1 hour for meat (less for fish). Step Seven Dig up the meat carefully. Step Eight Clean up and remember to Leave No Trace! Patrol Review Did you successfully build the oven? What was the hardest and easiest part ? Do you need to practice your fire lighting or cooking with foil skills more? What did you learn from it? What SPICES are relevant? Check them off on the next page Review SPICES. -

Resolution to Prevent Death of Kapampangan Langauge

RESOLUTION FOR THE ENACTMENT OF MEASURES TO PREVENT THE DEATH OF THE KAPAMPANGAN LANGUAGE Whereas more than 50% of the 7,000 languages spoken in the world may disappear in this century as less than a quarter of those languages are currently used in schools and in cy- berspace, and most are used only sporadically. Whereas the deterioration of Kapampangan, Waray, Pangasinan, Cebuano, Hiligaynon and other Philippine languages has been around since the term of President Quezon with the creation of a national language. This sad situation was further aggravated during the time of President Marcos, with the replacement of the mother tongue as medium of instruction in Grades I and II by the national language in addition to its already having a subject for itself in the curriculum. Whereas these two factors contribute greatly to their deterioration, prompting people to think that they have been virtually sentenced to DEATH by a state that wishes to have just one unified nation devoid of ethnic diversity. In 1985, a prominent Kapampangan civic leader and author predicted that Kapampangan would be dead in a hundred years. Based on observa- tions among the youngest schoolchildren in preschools and elementary schools, pupils who speak Kapampangan are now increasingly a minority. And their children will almost certainly be Tagalog. The death of Kapampangan may be much closer than we realize. Whereas cultural diversity is closely linked to linguistic diversity, as indicated in the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity and its action plan (2001), the Con- vention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005). -

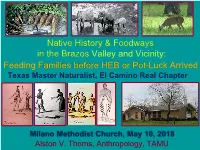

Historical and Archaeological Glimpses Into Ancient Native

Native History & Foodways in the Brazos Valley and Vicinity: Feeding Families before HEB or Pot-Luck Arrived Texas Master Naturalist, El Camino Real Chapter Milano Methodist Church, May 10, 2018 Alston V. Thoms, Anthropology, TAMU Tyler San Antonio Brazos County & the Post Oak Savannah, from San Antonio to Tyler, are environmentally similar to the oak-hickory-pine forests of eastern North America and hence more like Atlanta, GA than Amarillo, TX How to feed 30 this weekend, w/out HEB? How to feed 30 this weekend, w/out HEB? How to feed 30 this weekend, w/out HEB? Paleo-Indian Period prior to 10,000 years ago Acutualistic experiment results: 27 students attending a field school in South Africa, and working in groups of 3-5, broke these semi-fresh bones into small pieces in 15 minutes Field school and photographs by Dr. Lucinda Backwell, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2003 Mammoth bones, Duewall-Newberry site, Brazos River, near College Station Hunter-Gatherers-Fishers: Archaic Period: 10,000/8000 – 3500/1300 B.P. People worked down food chain (to smaller terrestrial animals, fish, & plants) for primary subsistence, exploiting more comparatively high-cost foods Hunter-Gatherers-Fishers of Late Pre- Columbian period & early Post-Columbian (aka Late-“Prehistoric” or “Formative” in areas w/ agriculture) ca. 2000/1300-150 B.P. Introduction of bow & arrow; sometimes pottery and/or agriculture into “Historic” era Late Pre-Columbian groups were immediate predecessors of historic-era “tribes” Agri- culture Little, if any, evidence for Agri- Agri- pre-Columbian culture culture Agri- agriculture culture west of Trinity Hunting River, as Agri- & agriculture culture Gathering never developed there and H&G lifeways persisted into Historic era Yegua Creek Archaeological Project late 1600s early 1700s Yerpibame Payaya Mixcal Xarame Post Oak Savannah is food-rich with a comparative abundance of deer and a variety of root food, as well as nuts, fruits, and berries, and some fish Cabeza de Vaca’s trek across S-C.