Collusive Litigation in the Early Years of the English Common Law: the Use of Mort D’Ancestor for Conveyancing Purposes C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

The British Historical Manuscripts Commission

THE BRITISH HISTORICAL MANUSCRIPTS COMMISSION V ' I HE establishment of the Royal Commission for Historical Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/7/1/41/2741992/aarc_7_1_m625418843u57265.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 Manuscripts in 1869 was an outgrowth of the concern for public records which had reached a climax only a few years earlier. As far back as 1661, William Prynne was appointed by Charles II to care for the public records in the Tower of London. Prynne described them as a "confused chaos, under corroding, putrifying cobwebs, dust and filth. ." In attempting to rescue them he employed suc- cessively "old clerks, soldiers and women," but all abandoned the job as too dirty and unwholesome. Prynne and his clerk cleaned and sorted them. He found, as he had expected, "many rare ancient precious pearls and golden records."1 Nevertheless, by 1800 the condition of the records was deplorable again, and a Record Commission was appointed for their custody and management. It was composed of men of distinction, was liberally supported, and it published various important documents. In spite of its work, the commission could not cope with the scattered records and unsuitable depositories. Of the latter, one was a room in the Tower of London over a gunpowder vault and next to a steam pipe passage; others were cellars and stables. The agitation aroused by the commission led to passage of the Public Records Act in 1838. The care and administration of the records was restored to the Mas- ter or Keeper of the Rolls, in conjunction with the Treasury depart- ment, with enlarged powers. -

Political Society in Cumberland and Westmorland 1471-1537

Political Society in Cumberland and Westmorland 1471-1537 By Edward Purkiss, BA (Hons). Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. School of History and Classics University of Tasmania. 2008. This Thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. 30 May, 2008. I place no restriction on the loan or reading of this thesis and no restriction, subject to the law of copyright, on its reproduction in any form. 11 Abstract The late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries have often been seen as a turning point in the development of the English state. At the beginning of the period the authority of the Crown was offset by powerful aristocratic interests in many regional areas. By the mid sixteenth century feudal relationships were giving way to a centrally controlled administration and government was reaching into regional political communities through direct connections between the Crown and local gentlemen. This thesis will trace these developments in Cumberland and Westmorland. It will argue that archaic aspects of government and society lingered longer here than in regions closer London. Feudal relationships were significant influences on regional political society well beyond the mid sixteenth century. This was a consequence of the area's distance from the centre of government and its proximity to a hostile enemy. -

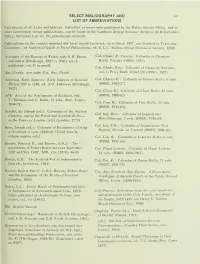

Bibliography and Xv List of Abbreviations

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY AND XV LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Full details of all Lists and Indexes, Calendars or transcripts published by the Public Record Office, and of other Government record publications, can be found in the handbook British National Archives (H.M. Stationery Office, Sectional List no. 24, periodically revised). Publications by the various national and local record societies, up to March 1957, are detailed in Texts and Calendars - an Analytical Guide to Serial Fhiblications, ed. E.L.C. Mullins (Royal Historical Society, 1958). Accounts of the Masters of Works, edd. H.M. Paton Cal. Chanc. R. Various: Calendar of Chancery and others (Edinburgh, 1957-). [Only vol. L Rolls, Various (HMSO, 1912) published; vol. II in proof]. Cal. Chanc. War.: Calendar of Chancery Warrants, Anc. Deeds: see under Cat. Anc. Deeds vol. i, Privy Seals 1244-1326 (HMSO, 1927) Anderson, Early Sources: Early Sources of Scottish Cal. Charter R.: Calendar of Charter Rolls, 6 vols. History 500 to 1286, ed. A.O. Anderson (Edinburgh, (HMSO, 1903-27) 1922) Cal. Close R.: Calendar of Close Rolls, 47 vols. APS: Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, edd. (HMSO, 1900-63) T. Thomson and C. Innes, 12 vols. (Rec. Comm., Cal. Fine R.: Calendar of Fine Rolls, 22 vols. 1844-75) (HMSO, 1911-63) Ayloffe, Sir Joseph (ed.): Calendars of the Ancient Cal. Inq. Misc.: Calendar of Inquisitions Charters, and of the Welch and Scottish Rolls.... Miscellaneous, 7 vols. (HMSO, 1916-69) in the Tower of London, [etc] (London, 1774) Cal. Inq. P.M.: Calendar of Inquisitions Post Bain, Joseph (ed.): Calendar of Documents relating Mortem, 19 vols, in 2 series (HMSO, 1904-56) to Scotland, 4 vols. -

The Long-Run Impact of the Dissolution of the English Monasteries

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE LONG-RUN IMPACT OF THE DISSOLUTION OF THE ENGLISH MONASTERIES Leander Heldring James A. Robinson Sebastian Vollmer Working Paper 21450 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21450 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 2015 We would like to thank Daron Acemoglu, Robert Allen, Josh Angrist, Rui Esteves, Joe Ferrie, Jeremiah Dittmar, Regina Grafe, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Joel Mokyr, Kevin O'Rourke, Orlando Patterson, Daniel Smail, Beth Truesdale, Noam Yuchtman and seminar participants at Harvard, Northwestern, Brown, Oxford, Göttingen, Münster, Mannheim, Heidelberg, ETH Zürich, Delhi School of Economics, Hertie School of Governance, the 2014 EEA meetings, the 2015 CEPR-NYU Economic History Conference and the NBER Development of the American Economy meeting for helpful comments, Bruce Campbell, James Dowey and Max Satchell for kindly sharing their data and Giovanni Zambotti for GIS assistance. We would like to thank Johannes Bettin, Kathrin Ellieroth, Wiebke Gumboldt, Jakob Hauth, Thiviya Kumaran, Amol Pai, Timo Stibbe and Juditha Wojcik for valuable research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Leander Heldring, James A. Robinson, and Sebastian Vollmer. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. -

Naming Shirehampton and the Name Shirehampton

Naming Shirehampton and the name Shirehampton Richard Coates University of the West of England, Bristol Shirehampton is a village in southern Gloucestershire, England, which has been absorbed into the city of Bristol. It has expanded into a suburb with a population of 6867 in 1991 (census figure; the precise figure is not readily deducible from later census data).1 Its territory included, until 1917, what was marshland and is now Avonmouth port and suburb. The historical development of its name is easy to follow in broad but unrevealing terms, though there is a considerable amount of problematic detail. In this article I explore what it is possible to deduce about aspects of the processes involved in its evolution, which are not at all straightforward. The paper can also be taken as an object lesson in the lexical-semantic and phonological difficulties of historical onomastics, and in the pleasures of travelling unexpected byways in the history of onomastics and in cultural history. But historical onomastics, in the sense of establishing the etymology of a name, is not the same as exploring the history of a name, and not the same as the historiography of a name. In analysing Shirehampton and its name, we shall look at all of these techniques and processes in detail. In this article I attempt to explore the historical onomasiological questions of what this particular tract of ground has been called over the centuries, and why; the semasiological question of the use of the place’s name or names in derived names (commemoration); and the historiographical question of what scholars have deduced from the place’s name or names: first and foremost the history of the interpretation of the place’s name or names (changing views on its/their etymology, and the consequences of changes in such provisional knowledge), but also changing views about the identification (denotation) of the name or names featuring in the record, and some real-world consequences of that. -

Victoria County History Style Guidelines for Editors

Victoria County History Style Guidelines for Editors v.1 September 2019 2 Contents Using the guidelines 3 Abbreviations 4 Bibliography 11 Capitalization 14 Dates 24 Figures and Numerals 28 Money 32 Names 34 People 35 Surnames 40 Forenames 43 Places 46 Punctuation 51 References 54 Recommended Usages 99 3 Using the guidelines This set of style guidelines is intended to form the latest revision of what was known as the ‘Handbook for Contributors’. We aim for this document to reflect current practices which naturally evolve over time. Please contact the VCH Central Office if you wish to suggest amendments and updates to the VCH Style Guide. General principles roman As used in this style guide, roman is a typographical term designating a style of lettering (in any typeface) in which characters are vertical (as distinguished from italic). Indexing Further guidance relating to VCH house style is available from central office. Abbreviations used throughout this guide ODNB - Oxford Dictionary of National Biography ODWE - Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors OED - Oxford English Dictionary 4 Abbreviations The authority for most points concerning abbreviations is the Oxford Guide to Style, Chapter 3, Abbreviations and Symbols. Try to make the abbreviations as intelligible as possible, even at the expense of slightly greater length. Short words are best not abbreviated; do not, for example, reduce ‘Feudal’ to ‘Feud.’ or ‘July’ to ‘Jul.’ In references excessive use of abbreviations in infrequently cited works is to be avoided. Works or institutions that are commonly cited in a particular volume should, however, be heavily abbreviated in that volume. -

PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE (Now National Archives) Texts And

PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE (now National Archives) Texts and Calendars Calendar of the charter rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Public Record Office, Texts and Calendars (1903-27) Vol. I: 11 - 41 Hen. III, 1226 -57. Vol. II: 42 Hen. III – 28 Edw. I, 1257 – 1300. Vol. III: 29 Edw. I – 20 Edw. II, 1300 – 26. Vol. IV: 1 – 14 Edw. III, 1327 – 41. Vol. V: 15 Edw. III – 5 Hen. V, 1341 – 1417. Vol. VI: 5 Hen. VI – 8 Hen. VIII, 1427 – 1516, with an appendix of charters and fragments of charters, 1215 – 88. Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Henry III, Public Record Office, Texts and Calendars (1901-13) Vol. I: Years 1 – 9, 1216 – 25. Vol. II: Years 10 – 16, 1225 – 32. Vol. III: Years 17 – 31, 1232 - 47. Vol. IV: Years 32 – 42, 1247 - 58. Vol. V: Years 43 – 50, 1258 - 66. Vol. VI: Years 51 – 57, 1266 – 72, with additions for November 1242 – July 1243 and for July – December 1262. Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Edward I, Public Record Office, Texts and Calendars (1893-1901) Vol. I: Years 1 – 9, 1272 - 81. Vol. II: Years 10 – 20, 1281 – 92, omitting some letters tested abroad, 1286 – 7, calendared in Vol. VI above. Vol. III: Years 21 – 29, 1292 - 1301. Vol. IV: Years 32 – 35, 1301 - 7. Calendar of the patent rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, Edward II, Public Record Office, Texts and Calendars (1893-1901) Vol. I: Years 1 – 6, 1307 - 13. Vol. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Manuscript Sources Alnwick, Alnwick Castle Archives Muniments, D.i.1a (Percy cartulary). Durham, Durham Cathedral Muniments 4.11.Spec.55. London, British Library Additional Charters: 20,559. BL Loan 41 (Rufford cartulary). Cotton Manuscripts: Otho C viii (Nunkeeling cartulary); Vespasian E xviii (Kirkstead Cartulary), xix (Nostell cartulary). Harley Charters: 50.F.32; 55.E.13; 57.E.24. Lansdowne MS: 424 (Meaux cartulary). Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Dodsworth viii. Oxford, St. John’s College Library MS 320, Pilkington Misc. 39. Whitehaven, Cumbria Record Office D/CU/4/173: Curwens of Workington Hall. Printed Primary Sources II Cnut, in English Historical Documents, c. 500–1042, ed. and trans. D. Whitelock, 2nd edn (London, 1955), vol. 1, 455–67. Abstracts of the Charters and other Documents contained in the Chartulary of the Cistercian Abbey of Fountains, ed. W.T. Lancaster, 2 vols (Leeds, 1915). Ari Þorgilsson, Íslendingabók, ed. Jakob Benediktsson, Íslenzk Fornrit I (Reyjavík, 1968). Be Wifmannes Beweddung, in English Historical Documents, c. 500–1042, ed. and trans. D. Whitelock, 2nd edn (London, 1979), vol. 1, 467–8. Birch, W. de G., Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum, 6 vols (London, 1887–1900). Book of Fees, see Liber Feodorum. Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, illustrative of the History of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 1 A.D. 918–1206, ed. J.H. Round (London, 1899). Calendar of the Close Rolls preserved in the Public Record Office, prepared under the superintendence of the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Edward I., vol. v A.D. 1302– 1307, HMSO (London, 1908). -

THE CECIL PAPERS: FOUR CENTURIES of CUSTODIAL HISTORY Early Dispersal of the Papers

THE CECIL PAPERS: FOUR CENTURIES OF CUSTODIAL HISTORY Early dispersal of the papers Historians of the Elizabethan and early Stuart period very quickly become aware of the dispersal of the papers of Lord Burghley and Robert Cecil amongst several different collections. These are chiefly those of the former State Paper Office at The National Archives, the Lansdowne Collection at the British Library and the Cecil Papers at Hatfield House. The State Paper Office originated in Queen Elizabeth's reign and some of Burghley's papers no doubt were always kept there or in his office at Whitehall. Many others were to hand in his own house: according to his will, his political papers concerning 'affaires of Counsell or state' were kept in his study over the porch and in certain other specified rooms in his London mansion, Burghley House. These papers he bequeathed to his son and political heir, Robert Cecil, who was Secretary of State at the time of his death. In due course they were moved to Salisbury House, which was built by Robert soon afterwards on the opposite side of the Strand. At the instigation of Robert Cecil, the powers of the State Paper Office were reinforced in 1610. One of his secretaries, Levinus Munck, and Thomas Wilson, his man of business, were appointed 'Keepers and Regesters' of the papers and records concerning matters of state and Council. The patent makes reference to the careful endeavours of Robert Earl of Salisbury, our Principal Secretary and our High Treasurer of England, to reduce all such papers, as well those that heretofore remained in the custody of Sir Thomas Lake, Knight, being the papers of some of the Principal Secretaries of our Predecessors, as also some such papers as he shall think fit to depart with, being either such as he hath collected of his own times, or such as were left to him from his late father the Lord Burghley, then Lord High Treasurer of England, into a set form or library, in some convenient place within our palace of Whitehall . -

The Case of the Medieval Irish Chancery Rolls

ILS 2013[13-14] 29/04/2013 19:11 Page 281 Reconstructing the past: the case of the medieval Irish chancery rolls PETER CROOKS* As we stood near the gate there was a loud shattering explosion … The munitions block and a portion of Headquarters block went up in flames and smoke … The yard was littered with chunks of masonry and smouldering records; pieces of white paper were gyrating in the upper air like seagulls. The explosion seemed to give an extra push to roaring orange flames which formed patterns across the sky. Fire was fascinating to watch; it had a spell like running water. Flame sang and conducted its own orchestra simultaneously. It can’t be long now, I thought, until the real noise comes. Ernie O’Malley, The Singing Flame 1 It is regrettable that so articulate an eyewitness as Ernie O’Malley (1897– 1959), sometime Irish revolutionary and self-styled aesthete, should have been utterly insensible to the iniquity of the event he describes: the cataclysmic fire at the Four Courts, Dublin, in 1922. 2 O’Malley’s ‘munitions block’ was in reality the record treasury of the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), part of the Four Courts complex occupied by IRA ‘Irregulars’ during the Easter vacation of 1922. After temporising for over two months, Free State forces began to shell the Four Courts on 28 June, and Ireland slipped into * Earlier versions of this paper were delivered in University College Dublin in November 2008 and as the Irish Legal History Society Spring discourse in February 2009. -

SN:5694 - Electronic Edition of Domesday Book: Translation, Databases and Scholarly Commentary, 1086

This document has been created by the History Data Service and is based on information supplied by the depositor SN:5694 - Electronic Edition of Domesday Book: Translation, Databases and Scholarly Commentary, 1086 Bibliography This is not a reading list for Domesday Book and is in no way intended to supplant Bates, A Bibliography of Domesday Book (1986), which can be supplemented by Hallam, 'Some Current Domesday Research Trends and Recent Publications', in Hallam and Bates, Domesday Book, pp. 191-198. The present list contains fuller details of books and articles cited in the notes where they have been given only short titles. This is essentially a working bibliography for those re-editing the Phillimore printed edition of Domesday Book and some books and articles are included relating to counties whose revision has yet to be published. The whole bibliography will receive a full revision, when completed. It has been the policy of this revision to expand all abbreviations (so, for example, UVL is now 'ultra-violet lamp'). The only remaining abbreviation of a book-title is VCH (Victoria County History). Contibutors to the notes are, however, referred to by their initials: Books and Articles cited in the Notes • Abels, 'Introduction', Bedfordshire Domesday ... R.P. Abels, 'An Introduction to the Bedfordshire Domesday', A. Williams and G. H. Martin (eds.), The Bedfordshire Domesday (London, 1991) pp. 1-53 • Abels, 'Introduction', Hertfordshire Domesday ... R.P. Abels, 'An Introduction to the Hertfordshire Domesday', A. Williams and G. H. Martin (eds.), The Hertfordshire Domesday (London, 1991) pp. 1-36. • Abels, 'Sheriffs'… Richard Abels, 'Sheriffs, Lord-seeking and the Norman Settlement of the South-East Midlands', Anglo-Norman Studies, 19 (1997) pp.