The Long-Run Impact of the Dissolution of the English Monasteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

Diocese of Chester Cycle of Prayer Sunday, 28 March to Saturday, 24

Diocese of Chester Cycle of Prayer Sunday, 28 March to Saturday, 24 April 2021 Sunday, 28 March 2021 Palm Sunday The disciples were weighed down. There had been dissension when the sons of Zebedee made a play for the places of authority at Christ's left and right. Soon there would be Jesus' dismaying words about the destruction of the Temple. Talk of his death would prompt them all to promises of death-defying loyalty. All too soon the promises will be found empty. Did they understand the donkey? The beast of common labour; rather than the war horse of power? Or were they weighed down with expectations of what a king's authority should look like? The palms gave Jesus and the animals the red-carpet treatment. No hoof or foot laid on bare cobbles. But didn't the disciples see that as a royal beginning, rather than the end of power plays? Jesus had sent them out (6.8) without money, nor extra shirt, nor food, or even a bag. Could there be a clearer instruction to leave the baggage behind? But it is so hard. The road of faith overturns our self-concern, forces us to leave our burdens aside, and calls us into unlikely, but joyful, company. Ours is a God of the brief encounter on the only journey that ultimately matters – the journey to him. And, lest the coming clouds of Friday obscure the way, we know also of two sad friends journeying to Emmaus who met their Risen Lord, and although they knew him not, it was like a fire burning within them. -

Chester Cathedral Strategic Plan 2018 – 2020

Chester Cathedral Strategic Plan 2018 – 2020 1 Contents 1. Foreword 2. About us 3. Our strategic framework 4. Delivering the vision 5. 2020 - 2030 Strategic planning 6. Contacts Photo Credits: Peter Smith 2 Foreword Chester Cathedral has been at the heart of the city of Chester for centuries and throughout its existence its custodians have developed strategies to deliver their vision. Today we continue in that tradition through this document, detailing our priorities for the next two transitional years and the development of a long term plan through to 2030. Chester Cathedral has developed significantly over the last 5 years; we have seen visitor numbers soar from 65,000 to over 300,000 in 2017. Our activities have broadened and deepened in their ambition and quality over this period. We have solved many of the core challenges which have curtailed the Cathedral’s development over the last few decades. It’s clear we still have a long way to go to achieve our vision for Chester and the Chester Diocese. With teamwork, a shared determination and great passion for our roles and the cathedral, I feel confident we will overcome our outstanding challenges and meet new ones as they come along. This is an exciting time to be part of Chester Cathedral. I look forward to watching it thrive through the period of this plan and to see the development of a long term sustainable strategy which will ensure a bright future for Chester Cathedral. The Revd Canon Jane Brooke Acting Dean 3 4 About us Chester Cathedral is a rare surviving example, in terms of condition and completeness, of a monastic complex transformed into a Cathedral. -

Statement of Needs

Diocese of Chester Statement of Needs Our diocese today 3 Who we are seeking 6 Our region 8 Cultural and social landscape 14 Ministry and mission 17 Finance and resources 30 Who’s who 31 Prayer 33 Contents 2 STATEMENT OF NEEDS 3 The Diocese of Chester The next Bishop of Chester will be joining a diocese in good heart, in a place where would like to express its Our there is much for which to treasure and thanks to Bishop Peter be thankful. diocese Forster who led and served The Diocese of Chester contains a rich this diocese for over 22 years. diversity of places, cultures and church traditions. Whilst there is an evangelical today centre of gravity to the diocese, there is a wide variety of traditions and a strong sense of family identity. Whoever is appointed must come with their eyes open and be able and willing to honour and embrace our distinctiveness and differences in tradition, theological conviction and opinion, for it is here that our greatest strength lies. STATEMENT OF NEEDS 4 The Diocese of Chester has retained a parish- Latest church statistics show an overall The next Bishop of Chester will focused approach, one that is well supported acceleration in previous trends towards and welcomed by clergy and laity alike. The decline and we are not neglectful or wilfully be joining the diocese at a time parish system is still believed in, and relatively blind to the reality we face. We seek a of great opportunity as we seek strong and healthy across the diocese. -

The British Historical Manuscripts Commission

THE BRITISH HISTORICAL MANUSCRIPTS COMMISSION V ' I HE establishment of the Royal Commission for Historical Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/7/1/41/2741992/aarc_7_1_m625418843u57265.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 Manuscripts in 1869 was an outgrowth of the concern for public records which had reached a climax only a few years earlier. As far back as 1661, William Prynne was appointed by Charles II to care for the public records in the Tower of London. Prynne described them as a "confused chaos, under corroding, putrifying cobwebs, dust and filth. ." In attempting to rescue them he employed suc- cessively "old clerks, soldiers and women," but all abandoned the job as too dirty and unwholesome. Prynne and his clerk cleaned and sorted them. He found, as he had expected, "many rare ancient precious pearls and golden records."1 Nevertheless, by 1800 the condition of the records was deplorable again, and a Record Commission was appointed for their custody and management. It was composed of men of distinction, was liberally supported, and it published various important documents. In spite of its work, the commission could not cope with the scattered records and unsuitable depositories. Of the latter, one was a room in the Tower of London over a gunpowder vault and next to a steam pipe passage; others were cellars and stables. The agitation aroused by the commission led to passage of the Public Records Act in 1838. The care and administration of the records was restored to the Mas- ter or Keeper of the Rolls, in conjunction with the Treasury depart- ment, with enlarged powers. -

FLH Journal 2013 (Pdf) Download

Journal of FRODSHAM AND DISTRICT HISTORY SOCIETY Issue No. 43 December 2013 CONTENTS History Society News 2 Wimark, the Anchoress of Frodsham – Pauline Lowrie 3-7 The Beauclerks of Kingsley – Colin Myles Wilson 8-10 Soldiers from Overseas at the Frodsham Hospital 1915-1919 Arthur R Smith 11-15 A Wartime Romance – Suzanne Parry 16-19 Historic Images Before 1914… the last years of peace And times of Empire Maurice Richardson 20-21 Two Clocks Unite...but not for long! Castle Park Clock’s Chiming Adventure – Dilys O’Neill 22-23 Clerical Tales – St Laurence Parish Church, Frodsham, and its Clergy Heather Powling 24-28 The Chester Cross – St. Luke’s Church Dunham-on-the-Hill Alan Pennell 29-31 And from the North a Great Army Came (Part II) – Ken Crouch 32-36 Archival News – Kath Hewitt 37-39 Programme of Meetings for 2014 40 Front cover picture: Dr Ellison, the Medical Officer, the Matron and a group of nurses at the Frodsham hospital during the First World War. On the left is Minnie May Duncalf whose life is described by Suzanne Parry in A Wartime Romance. The picture is from: Arthur Smith (2001) From Battlefield to Blighty – Frodsham Auxiliary Military Hospital 1915-1919 (Image enhanced by John Hughes, F&DPS). HISTORY SOCIETY NEWS Welcome to this 2013 edition of our History Society Journal President: Sir Alan Waterworth K.C.V.O Vice president: Mrs Joan Douglas Officers: Mrs E Wakefield, Hon. Chairman Dr K Gee, Hon. Secretary Mr A Wakefield, Hon. Treasurer Mrs M Dodd, Membership Secretary Committee: Mrs B Wainwright Mrs M Jones Mr B Keeble Mrs P Keeble Mrs D O’Neill Mr B Dykes Mrs D Coker Mr A Faraday This year we elected a new committee member, Mrs Deborah Coker, at the AGM and since then we have co-opted Mr Andrew Faraday to the committee. -

Political Society in Cumberland and Westmorland 1471-1537

Political Society in Cumberland and Westmorland 1471-1537 By Edward Purkiss, BA (Hons). Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. School of History and Classics University of Tasmania. 2008. This Thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. 30 May, 2008. I place no restriction on the loan or reading of this thesis and no restriction, subject to the law of copyright, on its reproduction in any form. 11 Abstract The late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries have often been seen as a turning point in the development of the English state. At the beginning of the period the authority of the Crown was offset by powerful aristocratic interests in many regional areas. By the mid sixteenth century feudal relationships were giving way to a centrally controlled administration and government was reaching into regional political communities through direct connections between the Crown and local gentlemen. This thesis will trace these developments in Cumberland and Westmorland. It will argue that archaic aspects of government and society lingered longer here than in regions closer London. Feudal relationships were significant influences on regional political society well beyond the mid sixteenth century. This was a consequence of the area's distance from the centre of government and its proximity to a hostile enemy. -

Cycle of Prayer

Cycle of Prayer 08 September 2019 - 11 January 2020 Diocese of Chester Key: C = Clergy LM = Licensed Lay Minister (Reader) (Pastoral Worker) (Youth Worker) Diocesan entries from the Anglican Cycle of Prayer are in italics. Chester Diocesan Board of Finance. Church House, 5500 Daresbury Park, Daresbury, Warrington WA4 4GE. Tel: 01928 718834 Chester Diocesan Board of Finance is a company limited by guarantee registered in England (no. 7826) Registered charity (no. 248968) Foreword I’ll never forget, after a long walk with my Dad, in Pendle, Lancashire, sipping a pint in a pub and chatting to the locals. Five minutes later I was surprised to turn to see my Dad placing his arthritic hand into the dirty palms of a particularly burly local farmer as they bowed their heads in prayer. I didn’t quite know where to look or what to do, so I lowered my head and kept quiet. It seemed like the right thing to do, and it helped me avoid the gaze of the growing number of amused boozy onlookers. That was my first and slightly embarrassing introduction to prayer. Since then I’ve travelled a long way, but I still remember the first tentative steps I took for myself. I also remember just how uncomfortable and alien praying felt to me. For those well versed in the lifelong discipline of prayer, it can perhaps be easy to forget just how strange the whole thing can be to start. I am grateful to one good colleague from many years ago who shared with me the William Temple quote: ‘When I pray, coincidences happen, when I don’t they don’t.’ As you pray during this period, please pray for those who are just starting and giving it a go. -

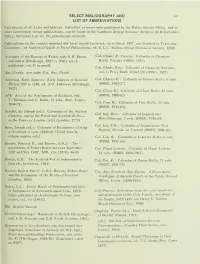

Bibliography and Xv List of Abbreviations

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY AND XV LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Full details of all Lists and Indexes, Calendars or transcripts published by the Public Record Office, and of other Government record publications, can be found in the handbook British National Archives (H.M. Stationery Office, Sectional List no. 24, periodically revised). Publications by the various national and local record societies, up to March 1957, are detailed in Texts and Calendars - an Analytical Guide to Serial Fhiblications, ed. E.L.C. Mullins (Royal Historical Society, 1958). Accounts of the Masters of Works, edd. H.M. Paton Cal. Chanc. R. Various: Calendar of Chancery and others (Edinburgh, 1957-). [Only vol. L Rolls, Various (HMSO, 1912) published; vol. II in proof]. Cal. Chanc. War.: Calendar of Chancery Warrants, Anc. Deeds: see under Cat. Anc. Deeds vol. i, Privy Seals 1244-1326 (HMSO, 1927) Anderson, Early Sources: Early Sources of Scottish Cal. Charter R.: Calendar of Charter Rolls, 6 vols. History 500 to 1286, ed. A.O. Anderson (Edinburgh, (HMSO, 1903-27) 1922) Cal. Close R.: Calendar of Close Rolls, 47 vols. APS: Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, edd. (HMSO, 1900-63) T. Thomson and C. Innes, 12 vols. (Rec. Comm., Cal. Fine R.: Calendar of Fine Rolls, 22 vols. 1844-75) (HMSO, 1911-63) Ayloffe, Sir Joseph (ed.): Calendars of the Ancient Cal. Inq. Misc.: Calendar of Inquisitions Charters, and of the Welch and Scottish Rolls.... Miscellaneous, 7 vols. (HMSO, 1916-69) in the Tower of London, [etc] (London, 1774) Cal. Inq. P.M.: Calendar of Inquisitions Post Bain, Joseph (ed.): Calendar of Documents relating Mortem, 19 vols, in 2 series (HMSO, 1904-56) to Scotland, 4 vols. -

Naming Shirehampton and the Name Shirehampton

Naming Shirehampton and the name Shirehampton Richard Coates University of the West of England, Bristol Shirehampton is a village in southern Gloucestershire, England, which has been absorbed into the city of Bristol. It has expanded into a suburb with a population of 6867 in 1991 (census figure; the precise figure is not readily deducible from later census data).1 Its territory included, until 1917, what was marshland and is now Avonmouth port and suburb. The historical development of its name is easy to follow in broad but unrevealing terms, though there is a considerable amount of problematic detail. In this article I explore what it is possible to deduce about aspects of the processes involved in its evolution, which are not at all straightforward. The paper can also be taken as an object lesson in the lexical-semantic and phonological difficulties of historical onomastics, and in the pleasures of travelling unexpected byways in the history of onomastics and in cultural history. But historical onomastics, in the sense of establishing the etymology of a name, is not the same as exploring the history of a name, and not the same as the historiography of a name. In analysing Shirehampton and its name, we shall look at all of these techniques and processes in detail. In this article I attempt to explore the historical onomasiological questions of what this particular tract of ground has been called over the centuries, and why; the semasiological question of the use of the place’s name or names in derived names (commemoration); and the historiographical question of what scholars have deduced from the place’s name or names: first and foremost the history of the interpretation of the place’s name or names (changing views on its/their etymology, and the consequences of changes in such provisional knowledge), but also changing views about the identification (denotation) of the name or names featuring in the record, and some real-world consequences of that. -

Prayer Diary May 2012 V2.Pub

Thursday 24th Workplace Chaplain—The Revd Chris Cullwick John and Charles Wesley, Please pray for: developing new chaplaincies eg in sport; enlisting yet more volunteers eg Street Diocese of York Prayer Diary --- May 2012 evangelists, Diocese of York Prayer Diary -- May 2012 hymn writers, Angels; the growing partnership with York St John University now offering supervision, 1791 and 1788 resources and training to support chaplaincy in the region and a launch conference event in Tuesday 1st Bishopthorpe Palace Philip and September; sustainability beyond next year when current BMO ends. James , Apostles The Archbishop of York, The Most Revd and Right Honourable Dr John Sentamu. Diocese of Chotanagpur (North India), Bishop B Baskey Chief of Staff: The Revd Malcolm Macnaughton, Chaplain Researcher: The Revd Dr Daphne Green, Friday 25th University of York St John Domestic Chaplain: The Revd Richard Carew and all the Staff at the Palace. The Venerable Please pray for the Archbishop and for all the staff working in support of the Archbishop’s Bede, monk, The Revd Lucas Njenga scholar, ministry in the Diocese, Province and Nation. historian, 735 Please pray for the students at this time when they are coming to the end of their studies. Also Diocese of Central Florida (IV The Episcopal Church), Bishop John Howe Aldhelm, bishop, for the safety of students who are in placements in Bangladesh, Uganda, Tanzania. Please pray 709 for the continuing strength of the community in the University. Wednesday2nd York Deanery Athanasius, Diocese of Christ the King (Southern Africa), Bishop Peter Lee bishop, teacher Rural Dean: The Revd Terence McDonagh of the faith, 373 Please pray for Terence McDonough who has taken on the role of Rural Dean of York from the Saturday 26th York Hospital Augustine, end of April 2012. -

Chester Diocesan Board of Finance

Chester Diocesan Board of Finance Annual Report and Financial Statements 2015 Diocese of Chester Cover Photo: Quilted wall hanging by Joanne Ridley Chester Diocesan Board of Finance Annual Report and Financial Statements 2015 Company limited by guarantee registered in England (no 7826) Registered charity (no 248968) Bankers: Auditors: National Westminster Bank plc BDO LLP 33 Eastgate Street 3 Hardman Street Chester Spinningfields CH1 1LG Manchester M3 3AT Charity Bank Solicitors: 182 High Street Tonbridge Cullimore Dutton Kent 20 White Friars TN9 1BE Chester CH1 1XS Investment managers: CCLA Investment Management Limited Senator House 85 Queen Victoria Street London EC4V 4ET Chester Diocesan Board of Finance Annual Report and Financial Statements 2015 Registered Office: Church House, 5500 Daresbury Park, Daresbury, Warrington WA4 4GE Telephone: (01928) 718 834 Chester Diocesan Board of Finance is the financial executive of the Church of England in the Diocese of Chester. It is a company limited by guarantee registered in England (no 7826) and is a registered charity (no 248968) Index Report of the trustees, incorporating the Strategic Report Membership of the Board 2 Chairman’s statement 3 Highlights of the year 4 Aims and Activities 5 Strategic report 6 Clergy 6 Assisting Parochial Church Councils 8 Parish Mission 8 Education 9 Social Responsibility 11 Ministry Development 12 Grants 12 Foxhill Spiritual Retreat and Conference 13 World Mission 13 Bishop of Stockport 14 Financial Review 14 Plans for future periods 15 Risk Management 15 Background information 16 Legal information 21 Statement of trustees’ responsibilities 22 Independent auditors’ report 23 Financial Statements Statement of Financial Activities 24 Balance Sheet 25 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Notes to the accounts 27 1 Membership of the Board (The trustees of the charity and the directors of the charitable company are the same.) Trustees/Directors served for the full year, except where shown.