Naming Shirehampton and the Name Shirehampton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

Shirehampton Remount Depot

Shirehampton Remount Depot During World War I the main form of transport for troops, munitions and supplies was the horse or mule. The military effort on the Western Front from August 1914 to November 1918 required a continual supply of these animals. Several Remount Depots were set up across the UK to help maintain this supply. Shirehampton was one of the largest and over 300,000 horses passed through Shirehapmton and Avonmouth between 1914 and 1918. There are no surviving physical remains and very few very few These images are used courtesy of the Shirehampton Book of images of the Remount Depot. Remembrance At the beginning of the war most of these http://shirehamptonbookofremembrance.webs.com/ horses came from British farms, but this supply was quickly exhausted. By 1915 most of the animals were shipped over from Canada or the US to be stabled at Shirehampton before they were sent to the front as required. Through the Heritage Lottery funded Shirehampton and Avonmouth All Our Stories project Myers-Insole Local Learning (MILL) aim to uncover stories of the men, their families and their experiences of the remount depot. These stories will There are a few drawings of the remount depot made by These two show buildings of the vetinary hospital that was part be presented on a World War I layer on Samuel Loxton immediately after the war in 1919. of the site and appears to have continued in use for a time. bristol.gov.uk/knowyourplace and will also be accessible at www.locallearning.org.uk. www.locallearning.org.uk Shirehampton Remount Depot A plan of the Shirehampton Remount Depot made in 1914 with later amendments held in the Building Plan books at Bristol Record Office (BRO BP Vol64a f56). -

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

Surrey Feet of Fines 1558-1760 Courtesy of Findmypast

Feet of Fines – Worcester references plus William Worcester publications: http://www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk Abstracts of Feet of Fines: Introduction The aim of this project is to provide abstracts of the medieval feet of fines that have not yet been published, for the period before 1509. A list of published editions, together with links to the abstracts on this site, can be found here. Alternatively, the abstracts can be searched for entries of interest. Background In the late 12th century a procedure evolved for ending a legal action by agreement between the parties. The agreement was known as a final concord (or fine). Originally this was a means of resolving genuine disputes, but by the middle of the 13th century the fine had become a popular way of conveying freehold property, and the legal action was usually a fictitious one, initiated with the cooperation of both parties. This procedure survived until the 1830s. Originally, each party would be given a copy of the agreement, but in 1195 the procedure was modified, so that three copies were made on a single sheet of parchment, one on each side and one at the foot. The copies would then be separated by cutting the parchment along indented (wavy) lines as a precaution against forgery. The right and left hand copies were given to the parties and the third copy at the foot was retained by the court. For this reason the documents are known as feet of fines. The following information is available online: Court of Common Pleas, General Eyres and Court of King's Bench: Feet of Fines Files, Richard I - Henry VII (to 1509) and Henry VIII - Victoria (from 1509) (descriptions of class CP 25 in The National Archives online catalogue) Land Conveyances: Feet of Fines, 1182-1833 (National Archives information leaflet) [Internet Archive copy from August 2004] CP 25/1/45/76, number 9. -

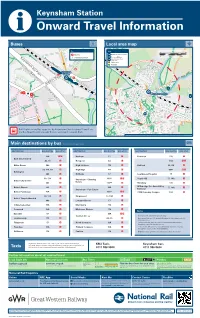

Keynsham Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Keynsham Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Key Key km 0 0.5 A Bus Stop LC Keynsham Leisure Centre 0 Miles 0.25 Station Entrance/Exit M Portavon Marinas Avon Valley Adventure & WP Wildlife Park istance alking d Cycle routes tes w inu 0 m Footpaths 1 B Keynsham C Station A A bb ey Pa r k M D Keynsham Station E WP LC 1 1 0 0 m m i i n n u u t t e e s s w w a a l l k k i i n n g g d d i i e e s s t t c c a a n n Rail Replacement Bus stops are by Keynsham Church (stops D and E on the Bus Map) Stop D towards Bristol, and stop E towards Bath. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at October 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP 19A A E Hanham 17 C Radstock 178 E Bath City Centre ^ A4, 39 E Hengrove A4 D 19A A E Bilbie Green 349 D High Littleton 178 E Saltford 39, A4 E 39, 178, A4 D Highridge A4 D 664* B E Brislington 349 E Hillfields 17 C Southmead Hospital 17 C 39, 178 D 663* B E Staple Hill 17, 19A C Keynsham - Chandag Bristol City Centre Estate 349 E 178** E Timsbury 178 E Willsbridge (for Avon Valley Bristol Airport A4 D 349 E 17, 19A C Keynsham - Park Estate Railway) Bristol Parkway ^ 19A C 665* B E UWE Frenchay Campus 19A C 39, 178 D Kingswood 17, 19A C Bristol Temple Meads ^ 349 E Longwell Green 17 C Cribbs Causeway 19A C Marksbury 178 E Downend 19A C Midsomer Norton 178 E Notes Eastville 17 C 19A A E Newton St Loe Bus routes 17, 39 and A4 operate daily. -

Local Resident Submissions to the Bristol City Council Electoral Review

Local resident submissions to the Bristol City Council electoral review This PDF document contains local resident submissions with surnames B. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. 13 February 2015 I have lived in Westbury on Trym village since 1991 first with my parents and then more recently with my own family. I have always valued the community which flows out from the historical village centre, under the new boundaries my home would no longer be part of this community and I would consider this a great personal loss. Surely the history and heritage of Westbury Village should carry some weight and significance when considering new ward boundaries. I fail to understand how it can be seen as acceptable to have the heart of Westbury on Trym Village boundaries moved to fall under the ward of Henleaze, which does not have the historic significance and village community. Also why it is acceptable for the downsized remaning part of Westbury Village to have only one councillor but this is not ok for any other ward. I therefore support the proposal to have a partnership ward with Henleaze and to share 3 councillors between us. I understand this is the only way to maintain the historical identity and preserve the integrity of the whole village. If other proposed changes were to go ahead I have concern for the value of my property as it would be separated from the historic village centre and fear that at some future date could be absorbed onto other wards. I would also like to include the following good reasons -

Keynsham Report

AVON EXTENSIVE URBAN SURVEY ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT REPORT KEYNSHAM DECEMBER 1999 AVON EXTENSIVE URBAN AREAS SURVEY - KEYNSHAM ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by Emily La Trobe-Bateman. I would like to thank the following people for their help and support: Vince Russett, project manager (Avon County Archaeologist subsequently North Somerset Archaeologist) and Dave Evans (Avon Sites and Monuments Officer, subsequently South Gloucestershire Archaeologist) for their comments on the draft report; Pete Rooney and Tim Twiggs for their IT support, help with printing and advice setting up the Geographical Information System (GIS) database; Bob Sydes (Bath and North East Somerset Archaeologist), who managed the final stages of the project; Nick Corcos for making the preliminary results of his research available and for his comments on the draft report; Lee Prosser for kindly lending me a copy of his Ph.D.; David Bromwich for his help locating references; John Brett for his help locating evaluations carried out in Keynsham.. Special thanks go to Roger Thomas, Graham Fairclough and John Scofield of English Heritage who have been very supportive throughout the life of the project. Final thanks go to English Heritage whose substantive financial contribution made the project possible. BATH AND NORTH EAST SOMERSET COUNCIL AVON EXTENSIVE URBAN AREAS SURVEY - KEYNSHAM CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The aims of the report 1 1.2 Major sources of evidence 1 1.3 A brief history of Keynsham 3 2.0 Prehistoric archaeology (pre-AD 47) 8 2.1 Sources -

Avon Bird Report 2008

AVON BIRD REPORT 2008 AVON ORNITHOLOGICAL GROUP Front cover: Great Crested Grebe. Photograph by Richard Andrews. Rear cover: Map of the Avon area computer generated by S. Godden, Dept. of Geography, University of Bristol. Text drawings by R.M. Andrews, J.P. Martin, R.J. Prytherch, B.E. Slade, the late L.A. Tucker and Anon. Typeset in WORD 2007 and printed by Healeys, Ipswich ISSN Number – 0956-5744 2 Avon Bird Report 2008 CONTENTS BTO advert Front cover Avon Ornithological Group (AOG) Front cover Editorial H.E. Rose 3 A guide to the records required by the Avon Bird Report 4 Species and subspecies for which descriptions are required 5 A review of 2008 R.J. Higgins 7 Weather in 2008 R.L. Bland 11 Migrant date summary 14 Introduction to systematic list 15 Contributors of records 18 Systematic list Swans and geese R. Mielcarek 19 Ducks M.S. Ponsford 23 Game birds R. Mielcarek 36 Divers to Spoonbill R.J. Higgins 38 Raptors B. Lancastle 45 Water Rail to Crane R. Mielcarek 53 Waders H.E. Rose 56 Skuas to Auks R.M. Andrews 71 Doves to Woodpeckers R. Mielcarek 83 Passerines, Larks to Dipper J. P. Martin 91 Passerines, Wren to Buntings R.L. Bland 97 Escaped, released and hybrid birds R Mielcarek 126 Birds of the Downs, 1994 - 2008 R.L. Bland 127 Metal pollution in Bristol: An assessment using bird of prey S. M. Murgatroyd 137 feathers Bitterns breeding at Chew Valley Lake 1997 - 2001 K. E. Vinicombe 143 Black-necked Grebes breeding at Chew Valley Lake in 1998 K. -

River Avon, Road & Rail Walk

F e r r y Riverside Heritage Walks R o 8 a d River Avon, Road 1 Old Lock & Weir / The Chequers & Rail Walk Londonderry 7 Wharf Riverside walk rich in historic and wildlife interest. Optional extension loop A4 exploring hidden woodlands and geology A 41 Somerdale 75 6 Route Description: Hanham pubs to Keynsham Lock or complete loop 2 1 Head east along the 60 mins 5 River Avon Trail. Loop: 100 mins Key 3 Route 4 See traces of the old 2 m / 3.25 km Route guide Londonderry Wharf Loop: 4.5 / 7.25 km 1 The Lock Keeper River Avon Trail and The Dramway Level, grassy Short cut that once carried paths coal from Kingswood Loop: Some steep Refreshments Keynsham to the river. Look out steps, rough ground Shop for cormorants. and high stiles Pub You will see the development at former Cadbury’s Somerdale factory Arrive at Keynsham Lock on the – the site of a Roman town. Kennet & Avon Canal. Continue 2 beneath the old bridge beside The Lock Keeper pub, and up onto the bridge. You can now retrace your steps to the start or continue on loop walk. Drop down along the path over When you have crossed both the rail Route extension the wild grassland, keeping the 5 and river bridge, turn right and zig- Turn left and left again to road close by on your right. zag uphill to find a wooden stile. arrive on the main road The grassy path is bordered by Cross here and drop down sharply (A4175). -

Catalogue of Adoption Items Within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window

Catalogue of Adoption Items within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window The cloister Windows were created between 1916 and 1999 with various artists producing these wonderful pictures. The decision was made to commission a contemplated series of historical Windows, acting both as a history of the English Church and as personal memorials. By adopting your favourite character, event or landscape as shown in the stained glass, you are helping support Worcester Cathedral in keeping its fabric conserved and open for all to see. A £25 example Examples of the types of small decorative panel, there are 13 within each Window. A £50 example Lindisfarne The Armada A £100 example A £200 example St Wulfstan William Caxton Chaucer William Shakespeare Full Catalogue of Cloister Windows Name Location Price Code 13 small decorative pieces East Walk Window 1 £25 CW1 Angel violinist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW2 Angel organist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW3 Angel harpist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW4 Angel singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW5 Benedictine monk writing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW6 Benedictine monk preaching East Walk Window 1 £50 CW7 Benedictine monk singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW8 Benedictine monk East Walk Window 1 £50 CW9 stonemason Angel carrying dates 680-743- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW10 983 Angel carrying dates 1089- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW11 1218 Christ and the Blessed Virgin, East Walk Window 1 £100 CW12 to whom this Cathedral is dedicated St Peter, to whom the first East Walk Window 1 £100 CW13 Cathedral was dedicated St Oswald, bishop 961-992, -

Level 1: Citywide Strategic Flood Risk Assessment

Level 1 – Citywide Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Contents Purpose of the document .................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Background and strategic planning ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Context .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Planning Policy ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.4 Applying the Sequential Test ............................................................................................... 8 1.5 Flood Risk Management Plan .............................................................................................. 8 1.6 Flood risk and water management policy and guidance ................................................. 9 2.0 Flood risk in Bristol .................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Sources of flooding ................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 River systems and watercourses in Bristol ...................................................................... 10 2.3 Geology ................................................................................................................................