“Even If It Means Our Battles to Date Are Meaningless” the Anime Gundam Wing and Postwar History, Memory, and Identity in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media

i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i Herlander Elias The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media LabCom Books 2012 i i i i i i i i Livros LabCom www.livroslabcom.ubi.pt Série: Estudos em Comunicação Direcção: António Fidalgo Design da Capa: Herlander Elias Paginação: Filomena Matos Covilhã, UBI, LabCom, Livros LabCom 2012 ISBN: 978-989-654-090-6 Título: The Anime Galaxy Autor: Herlander Elias Ano: 2012 i i i i i i i i Índice ABSTRACT & KEYWORDS3 INTRODUCTION5 Objectives............................... 15 Research Methodologies....................... 17 Materials............................... 18 Most Relevant Artworks....................... 19 Research Hypothesis......................... 26 Expected Results........................... 26 Theoretical Background........................ 27 Authors and Concepts...................... 27 Topics.............................. 39 Common Approaches...................... 41 1 FROM LITERARY TO CINEMATIC 45 1.1 MANGA COMICS....................... 52 1.1.1 Origin.......................... 52 1.1.2 Visual Style....................... 57 1.1.3 The Manga Reader................... 61 1.2 ANIME FILM.......................... 65 1.2.1 The History of Anime................. 65 1.2.2 Technique and Aesthetic................ 69 1.2.3 Anime Viewers..................... 75 1.3 DIGITAL MANGA....................... 82 1.3.1 Participation, Subjectivity And Transport....... 82 i i i i i i i i i 1.3.2 Digital Graphic Novel: The Manga And Anime Con- vergence........................ 86 1.4 ANIME VIDEOGAMES.................... 90 1.4.1 Prolongament...................... 90 1.4.2 An Audience of Control................ 104 1.4.3 The Videogame-Film Symbiosis............ 106 1.5 COMMERCIALS AND VIDEOCLIPS............ 111 1.5.1 Advertisements Reconfigured............. 111 1.5.2 Anime Music Video And MTV Asia......... -

Imagined Identity and Cross-Cultural Communication in Yuri!!! on ICE Tien-Yi Chao National Taiwan University

ISSN: 2519-1268 Issue 9 (Summer 2019), pp. 59-87 DOI: 10.6667/interface.9.2019.86 Russia/Russians on Ice: Imagined Identity and Cross-cultural Communication in Yuri!!! on ICE tien-yi chao National Taiwan University Abstract Yuri!!! on ICE (2016; 2017) is a Japanese TV anime featuring multinational figure skaters com- peting in the ISU Grand Prix of Figure Skating Series. The three protagonists, including two Russian skaters Victor Nikiforov, and Yuri Purisetsuki (Юрий Плисецкий), and one Japanese skater Yuri Katsuki (勝生勇利), engage in extensive cross-cultural discourses. This paper aims to explore the ways in which Russian cultures, life style, and people are ‘glocalised’ in the anime, not only for the Japanese audience but also for fans around the world. It is followed by a brief study of Russian fans’ response to YOI’s display of Russian memes and Taiwanese YOI fan books relating to Russia and Russians in YOI. My reading of the above materials suggests that the imagined Russian identity in both the official anime production and the fan works can be regarded as an intriguing case of cross-cultural communication and cultural hybridisation. Keywords: Yuri!!! on ICE, Japanese ACG (animation/anime, comics, games), anime, cross-cul- tural communication, cultural hybridisation © Tien-Yi Chao This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. http://interface.ntu.edu.tw/ 59 Russia/Russians on Ice: Imagined Identity and Cross-cultural Communication in Yuri!!! on ICE Yuri!!! on ICE (ユーリ!!! on ICE; hereinafter referred to as YOI)1 is a TV anime2 broadcast in Japan between 5 October and 21 December 2016, featuring male figure skaters of various nationalities. -

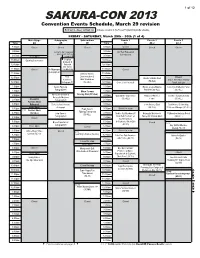

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Ilias Bulaid

Ilias Bulaid Ilias Bulaid (born May 1, 1995 in Den Bosch, Netherlands) is a featherweight Ilias Bulaid Moroccan-Dutch kickboxer. Ilias was the 2016 65 kg K-1 World Tournament Runner-Up and is the current Enfusion 67 kg World Champion.[1] Born 1 May 1995 Den Bosch, As of 1 November 2018, he is ranked the #9 featherweight in the world by Netherlands [2] Combat Press. Other The Blade names Titles Nationality Dutch Moroccan 2016 K-1 World GP 2016 -65kg World Tournament Runner-Up[3] 2014 Enfusion World Champion 67 kg[4] (Three defenses; Current) Height 178 cm (5 ft 10 in) Weight 65.0 kg (143.3 lb; Professional kickboxing record 10.24 st) Division Featherweight Style Kickboxing Stance Orthodox Fighting Amsterdam, out of Netherlands Team El Otmani Gym Professional Kickboxing Record Date Result Opponent Event Location Method Round Time KO (Straight 2019- Wei Win Wu Linfeng China Right to the 3 1:11 06-29 Ninghui Body) 2018- Youssef El Decision Win Enfusion Live 70 Belgium 3 3:00 09-15 Haji (Unanimous) 2018- Hassan Wu Linfeng -67KG Loss China Decision (Split) 3 3:00 03-03 Toy Tournament Final Wu Linfeng -67KG 2018- Decision Win Xie Lei Tournament Semi China 3 3:00 03-03 (Unanimous) Finals Kunlun Fight 67 - 2017- 66kg World Sanya, Decision Win 3 3:00 11-12 Petchtanong Championship, China (Unanimous) Banchamek Quarter Finals Despite winning fight, had to withdraw from tournament due to injury. Kunlun Fight 65 - 2017- Jordan Kunlun Fight 16 Qingdao, KO (Left Body Win 1 2:25 08-27 Kranio Man Tournament China Hook) 67 kg- Final 16 KO (Spinning 2017- Manaowan Hoofddorp, Win Fight League 6 Back Kick to The 1 1:30 05-13 Netherlands Sitsongpeenong Body) 2017- Zakaria Eindhoven, Win Enfusion Live 46 Decision 5 3:00 02-18 Zouggary[5] Netherlands Defends the Enfusion -67 kg Championship. -

GLORY CSR Report 2016

GLORY LTD. 1-3-1 Shimoteno, Himeji, Hyogo 670-8567, Japan Phone: +81-79-297-3131 Fax: +81-79-294-6233 http://www.glory-global.com For further information: Corporate Communications Department Phone: +81-79-294-6317 Fax: +81-79-299-6292 GLORY CSR Report 2016 Cover: GLORY produced Japan’s first coin counter, which was recognized as a Mechanical Engineering Heritage in 2015. For more details, see Special Report 2 on pages 9 and 10 of this report. GLORY at a Glance Editorial Policy Table of Contents Corporate name : GLORY LTD. Stock listings : Tokyo Stock Exchange (1st Section) The GLORY CSR Report 2016 aims to inform a wide range of Message from the President 3 Founded : March 1918 Number of employees : 3,244 (Group: 9,093) stakeholders about the CSR initiatives that GLORY LTD. and Note: As of March 31, 2016 Incorporated : November 1944 GLORY Group companies conducted during fiscal year 2015. Line of business : Development, manufacturing, sales, and maintenance of This report contains information in line with the Standard Capital : ¥12,892,947,600 money handling machines, data processing equipment, Disclosures of the Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, Version 4 peripheral devices, vending machines, automatic service set out by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). GLORY is also in equipment, etc. the process of identifying material issues in line with the relevant process defined by the GRI. Business Segments Special Report 1 outlines major CSR initiatives for each stakeholder category in the value chain. Special Report 2 Corporate Philosophy introduces the history of GLORY products. The GLORY CSR Report Customers Main Products and Goods and Management Creed 5 2016 also covers major efforts in fiscal year 2015 related to and Secure Soci environmental protection, social action, and corporate Safe ety Financial Market Open teller systems Cash monitoring cabinets Coin and banknote recyclers Security storage systems governance. -

Bandai June New Product

Bandai June New Product ZZ II "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBF 1/144 Launching alongside the release of a new Gundam Build Fighters Try episode, the popular Z II is now available! Capable of transforming into its Wave Rider form, the model kit also comes with powerful large-scale weaponry. Set includes a large beam rifle, transformation replacement parts, and interchangeable hand. Runner x12. Foil Sticker x1. Instruction manual x1. Approximately 5.5" Tall Package Size: Approximately 12.2"x7.8"x3.1" MSRP: $27.99 Gyancelot "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBF 1/144 From the Gyan family, comes a new model kit featuring Gyancelot! With expert detailing on the shield and weapons, the color scheme and textures accurately reproduces the look from the anime! The large lance appears in the shape of the crest of the Principality of Zeon, and its blades can be opened or closed through the use of replacement parts. Set includes large lance, beam saber, shield, and interchangeable hands. Runner x11. Foil sticker x1. Instruction manual x1. Approx. 5" Tall Package Size: Approx. 11.7"x7.4"x3.0" MSRP: $19.99 Gya Eastern Weapons "Gundam Build Fighters", Bandai HGBC 1/144 This is a kit focusing on parts for hand-held weapons from the Build Custom series! The parts can be used to customize existing models from various 1/144 series. The large rifle from the HG 1/144 ZZ II can be combined with a newly molded clay bazooka and optional parts for the lance from the Gyancelot can be customized as well. -

Theme Exploration and Authorial Intent in Mobile Suit Gundam

Looking towards the future: Theme exploration and authorial intent in Mobile Suit Gundam Bachelor’s thesis Kim Ilomäki University of Jyväskylä Department of Language and Communication English 5.2020 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunta Kieli- ja viestintätieteiden laitos Tekijä – Author Kim Ilomäki Työn nimi – Title Looking towards the future: Theme exploration and authorial intent in Mobile Suit Gundam Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Englannin kieli Kandidaatintutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Toukokuu 2020 16 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Mobile Suit Gundam on vuonna 1979 julkaistu TV anime sarja, joka oli omana aikanaan erittäin vaikutusvaltainen ja joka jatkaa olemassaoloaan monissa eri muodoissa. Sarjaa on tutkittu ennenkin mutta tekijä Yoshiyuki Tominon pääteemasta ei ole tehty merkittävää tutkimusta. Tässä tutkimuksessa analysoidaan Yoshiyuki Tominon omin sanoin kuvaavaa teemaa; ’aikuiset ovat vihollisia.’ Sarjan tarina sijoittuu sci-fi tulevaisuuteen, jossa ihmiset ovat rakentaneet siirtokuntia avaruuteen Maan ympärille. Tarinan konflikti kertoo sodasta joka on syttynyt avaruudessa ja Maassa asuvien ihmisten välillä. Tarinan suurin vaikutus omalla ajallaan oli näyttää todenmukaista sodankäyntiä, jossa kumpikaan osapuoli sodassa ei ollut hyvä eikä paha. Tarinan päähenkilöt koostuvat nuorista henkilöistä jotka joutuvat ottamaan osaa sotaan vastoin heidän tahtoaan. Käytän aineistolähtöistä analyysia tuodakseni esiin toistuvia teemoja tarinassa -

Hypersphere Anonymous

Hypersphere Anonymous This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ISBN 978-1-329-78152-8 First edition: December 2015 Fourth edition Part 1 Slice of Life Adventures in The Hypersphere 2 The Hypersphere is a big fucking place, kid. Imagine the biggest pile of dung you can take and then double-- no, triple that shit and you s t i l l h a v e n ’ t c o m e c l o s e t o o n e octingentillionth of a Hypersphere cornerstone. Hell, you probably don’t even know what the Hypersphere is, you goddamn fucking idiot kid. I bet you don’t know the first goddamn thing about the Hypersphere. If you were paying attention, you would have gathered that it’s a big fucking 3 place, but one thing I bet you didn’t know about the Hypersphere is that it is filled with fucked up freaks. There are normal people too, but they just aren’t as interesting as the freaks. Are you a freak, kid? Some sort of fucking Hypersphere psycho? What the fuck are you even doing here? Get the fuck out of my face you fucking deviant. So there I was, chilling out in the Hypersphere. I’d spent the vast majority of my life there, in fact. It did contain everything in my observable universe, so it was pretty hard to leave, honestly. At the time, I was stressing the fuck out about a fight I had gotten in earlier. I’d been shooting some hoops when some no-good shithouses had waltzed up to me and tried to make a scene. -

Protoculture Addicts #61

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF WHAT'S GOING ON? ANIME & MANGA NEWS .......................................................................................................... 5 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager VIDEO & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................... 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES .............................................................................................................. 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 10 MODEL NEWS ...................................................................................................................... 47 Contributors Aaron Dawe Kevin Lilliard, James S. Taylor REVIEWS Layout LIVE-ACTION ........................................................................................................................ 15 MODELS .............................................................................................................................. 46 The Safe House MANGA .............................................................................................................................. 54 Cover PA PICKS ............................................................................................................................ -

Continuing to Innovate with a Focus on Global Business Initiatives Aligned with Changes in Our Markets

NEWSLETTER September 2018 BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Mirai-Kenkyusho 5-37-8 Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-0014 Mitsuaki Taguchi Interview with the President President & Representative Director, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Continuing to innovate with a focus on global business initiatives aligned with changes in our markets Under the Mid-term Plan, the Group announced a mid-term vision of CHANGE for the NEXT — Empower, Gain Momentum, and Accelerate Evolution, and launched a five-Unit system. In the first quarter, the Group achieved record-high sales. In these ways, the Mid-term Plan has gotten off to a favorable start. In this issue of the newsletter, BANDAI NAMCO Holdings’ President Mitsuaki Taguchi discusses the future results forecast and the situation with each of the Group’s Units. How were the results in the first What is the outlook for the future? for the mature fan base, BANDAI SPIRITS quarter? Taguchi: In our industry, the environment is CO., LTD., a new company that consolidates Taguchi: In the first quarter of FY2019.3, in undergoing drastic changes, and it is difficult the mature fan base business of the Toys and comparison with the same period of the previous to forecast all of the future trends based on Hobby Unit, started fullscale operation. With year, each business recorded favorable overall three months of results. Considering bolstered a separate organizational structure and a clarified progress with core IP* and products/services, marketing and promotion for businesses mission, the sense of speed in this business despite differences in the home video game recording favorable results; recent business has increased. -

Aachi Wa Ssipak Afro Samurai Afro Samurai Resurrection Air Air Gear

1001 Nights Burn Up! Excess Dragon Ball Z Movies 3 Busou Renkin Druaga no Tou: the Aegis of Uruk Byousoku 5 Centimeter Druaga no Tou: the Sword of Uruk AA! Megami-sama (2005) Durarara!! Aachi wa Ssipak Dwaejiui Wang Afro Samurai C Afro Samurai Resurrection Canaan Air Card Captor Sakura Edens Bowy Air Gear Casshern Sins El Cazador de la Bruja Akira Chaos;Head Elfen Lied Angel Beats! Chihayafuru Erementar Gerad Animatrix, The Chii's Sweet Home Evangelion Ano Natsu de Matteru Chii's Sweet Home: Atarashii Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Ha Ao no Exorcist O'uchi Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Jo Appleseed +(2004) Chobits Appleseed Saga Ex Machina Choujuushin Gravion Argento Soma Choujuushin Gravion Zwei Fate/Stay Night Aria the Animation Chrno Crusade Fate/Stay Night: Unlimited Blade Asobi ni Iku yo! +Ova Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Works Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Clannad Figure 17: Tsubasa & Hikaru Azumanga Daioh Clannad After Story Final Fantasy Claymore Final Fantasy Unlimited Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children B Gata H Kei Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Baccano! R2 Freedom Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Colorful Fruits Basket Bakemonogatari Cossette no Shouzou Full Metal Panic! Bakuman. Cowboy Bebop Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu + TSR Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Coyote Ragtime Show Furi Kuri Irohanihoheto Cyber City Oedo 808 Fushigi Yuugi Bakuretsu Tenshi +Ova Bamboo Blade Bartender D.Gray-man Gad Guard Basilisk: Kouga Ninpou Chou D.N. Angel Gakuen Mokushiroku: High School Beck Dance in -

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fred A

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-SIX This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archcological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents. GEORGE WASHINGTON BIRTHPLACE National Monument Virginia by J. Paul Hudson NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 26 Washington, D. C, 1956 The National Park System, of which George Washington Birthplace National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Qontents Page JOHN WASHINGTON 5 LAWRENCE WASHINGTON 6 AUGUSTINE WASHINGTON 10 Early Life 10 First Marriage 10 Purchase of Popes Creek Farm 12 Building the Birthplace Home 12 The Birthplace 12 Second Marriage 14 Virginia in 1732 14 GEORGE WASHINGTON 16 THE DISASTROUS FIRE 22 A CENTURY OF NEGLECT 23 THE SAVING OF WASHINGTON'S BIRTHPLACE 27 GUIDE TO THE AREA 33 HOW TO REACH THE MONUMENT 43 ABOUT YOUR VISIT 43 RELATED AREAS 44 ADMINISTRATION 44 SUGGESTED READINGS 44 George Washington, colonel of the Virginia militia at the age of 40. From a painting by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy, Washington and Lee University. IV GEORGE WASHINGTON "... His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives .