Arctic Simulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sommario Rassegna Stampa

Sommario Rassegna Stampa Pagina Testata Data Titolo Pag. Rubrica Marina Militare - Siti Web Assovela.it 29/04/2017 LA NAVAL ACADEMIES REGATTA CON FORMAT LIV 2 Altopascio.info 28/04/2017 [ REGIONE TOSCANA ] SCUOLA E MARE, GRIECO: "STUDENTI 3 PROTAGONISTI GRAZIE AD ACCADEMIA E TIRRENO" Cervianotizie.it 28/04/2017 VELA / BUON QUINTO POSTO DI MAGICA FATA ALLA TAPPA 5 LIVORNESE DEL CIRCUITO NAZIONALE J24 Farevela.net 28/04/2017 LE ACCADEMIE NAVALI IN REGATA A LIVORNO 7 Giornalelora.com 28/04/2017 LEGA ITALIANA VELA:PRESENTATI GLI EQUIPAGGI DELLA NAVAL 9 ACADEMIES REGATTA CON FORMAT LIV ALLA CERIMO Italiavela.it 28/04/2017 PRESENTATI GLI EQUIPAGGI DELLA NAVAL ACADEMIES REGATTA 13 Pressmare.it 28/04/2017 FIV: PRESENTATI GLI EQUIPAGGI PARTECIPANTI ALLA NAVAL 14 ACADEMIES REGATTA Toscana-Notizie.it 28/04/2017 SCUOLA E MARE, GRIECO: "STUDENTI PROTAGONISTI GRAZIE AD 15 ACCADEMIA E TIRRENO" Velaveneta.it 28/04/2017 LE ACCADEMIE NAVALI SI SFIDANO A SUON DI VIRATE A LIVORNO 16 Data 29-04-2017 Pagina Foglio 1 MENU 28/04/2017 LA NAVAL ACADEMIES REGATTA CON FORMAT LIV Home News Acronimi Sigle Nazioni DIXPLAY PRESENTATI IERI SERA GLI EQUIPAGGI PARTECIPANTI ALLA NAVAL ACADEMIES REGATTA CON FORMAT LIV ALLA CERIMONIA DI CONSEGNA DELLE BANDIERE In casa e, a maggior ragione in barca è possibile risparmiare corrente elettrica con le lampade a led Livorno, 28 aprile 2017 - Si è aperta ufficialmente ieri sera, con una straordinaria cerimonia di consegna delle http://www.dixplay.it bandiere caratterizzata da un'emozionante marzialità, la "Naval Academies Regatta" organizzata dall'Accademia Navale di Livorno nell'ambito della Settimana Velica Internazionale Accademia Navale e Città di Livorno. -

1 Hellenic Naval Academy (Hna) Erasmus+ Policy

HELLENIC NAVAL ACADEMY (HNA) ERASMUS+ POLICY STATEMENT Modern higher educational processes require the international cooperation of HNA with other Military and Civil Educational institutions of European countries and the rest of the world, in order to promote scientific research and expertise, military training, improve the educational operations at all levels - undergraduate, postgraduate - and to disseminate the cultural heritage between the countries. HNA adopted a strategy for the development of the cooperation that will be determined by high quality standards of the partner institutions, concerning students, staff (both Academic and Military) and educational and research infrastructures. The intentention of the HNA is to play a leading role at the development of inter-university cooperation at all subjects of naval science, technical engineering science, environmental science, basic sciences, law science, as well as economics and humanities. Particularly in the educational objective, HNA will endorse the cooperation in the Military Erasmus Initiative and expanded this with cooperation with other European Institutions (civil and military). Additionally in the research field, HNA will investigate the cooperation possibilities with recognized international institutions for the establishment of research infrastructures, which can improve the basic research capabilities of HNA, incorporate innovative applications for life improvement. The utilization of HNA’s high level human resources and the exceptional level of infrastructure are the key elements for the achievement of the objective of inter-university cooperation. The role of HNA is well established through history. It is one of the oldest institutions in Greece established in 1845. The important role of HNA not only in European, Balkan and Mediterranean countries but also in those of Middle East, Asia, Africa and American continents, can and must be emerged through rational planning and targeted strategy steps. -

GREECE Navy.Pdf

GREECE How to Become a Military Officer in the Greek Armed Forces: The basic education and training of the officers of the Greek Army, Navy and Air Force is primarily the responsibility of three respective academies. The national conscript service contributes also to the training of the future military elites. These academies, which are used to educate and train officers also for foreign armed forces, are now on the way to integrate the acquis of the European Higher Education Area in order to obtain the instruments, which will allow them developing further their exchange capacities. These academies, indeed, provide academic curricula at the first cycle level. In addition, the Army Academy proposes postgraduate curricula as a part of the intermediate – or advanced – education of the Greek officers. The Air Force Academy also intends to develop its educational offer in proposing in the future a master curriculum on flight safety. The vocational training of the future Greek and Cypriot military elites, since they are fully trained in the Greek institutions, is also assured by the academies, in cooperation with the specialist training centres. NAVY Hellenic Naval Academy (http://www.hna.gr/snd/index.html) Academic curricula Military specialisations Naval Sciences and Navigation Seamanship (specialisation offered Weapons (basic (basic education) for line officers or Branch School (Skaramagas, Athens) Bachelor Bachelor Anti-Submarine engineers) Communications Mechanical Engineering Number of cadets first year: 35 Total number of cadets: 200 -

Curriculum Vitae of Lieutenant Nikolaos Petrakos HN

Curriculum Vitae of Admiral Evangelos Apostolakis HN CHIEF of Hellenic National Defence General Staff Admiral Evangelos Apostolakis HN, was born in Rethymnon Crete on May 14th, 1957. He joined the Hellenic Naval Academy in 1976 and was commissioned as Ensign of the Hellenic Navy in July 1980. He was promoted to: Lieutenant Junior Grade 1983 Lieutenant 1987 Lieutenant Commander 1992 Commander 1997 Captain 2004 Commodore 2009 Rear Admiral 2011 Vice Admiral 2012 Admiral 2015 He has completed the Underwater Demolitions Team School of the Hellenic Navy and he is a graduate of the Advance Mine Warfare School (Belgium), Amphibious Warfare School USMC (USA) and Hellenic Navy War College. His sea duty assignments include various tours. He served mainly on Destroyers and Amphibious ships as Communication, Navigation and Operations Officer. He served as the Commanding Officer of MSC HS ATALANTI, MSC HS KISSA and FFGH HS NAVARINON. His shore and staff assignments include service as Deputy Commander and Commander of the Underwater Demolition Command, Adjutant of the Minister of National Defence, Director of Administration of Souda Naval Base, Chief of Staff of Senior Naval Command Aegean and Deputy Chief of Staff STRIKEFORNATO. As Commodore he assumed duties of Director of the Hellenic Navy General Staff Personnel Branch. As Rear Admiral he was assigned Deputy Commander in Chief of Hellenic Fleet and Chief of Staff of Hellenic National Defence General Staff. Promoted to Vice Admiral, he served as Deputy Chief of Hellenic National Defence General Staff. On March 7th 2013, he was appointed Chief of Hellenic Navy General Staff. On September 15th 2015, upon decision of the Governmental Council for Foreign Affairs and Defence, he assumed the duty of Chief of Hellenic National Defence General Staff and was promoted to Admiral. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

WP6 Implementation of Recommendations

Ref. Ares(2020)6696168 - 13/11/2020 HORIZON 2020 D8.2 External Advisory Board (EAB) Report, Version 2 Augmented Reality Enriched Situation awareness for Border security ARESIBO – GA 833805 Deliverable Information Deliverable Number: D8.2 Work Package: #8 Date of Issue: 05/11/2020 Document Reference: N/A Version Number: 1.0 Nature of Deliverable: Dissemination Level of Deliverable: Report Public Author(s): Fraunhofer IML Keywords: External Advisory Board, Stakeholder, external experts Abstract: The EAB Activity Report describes the selection process of the EAB in ARESIBO as well as responsibilities, limitations and characteristics. In addition, this second report describes the involvement of the EAB in the first half of the project. The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 833805. D8.2 EAB Report V2 Legal Disclaimer This document reflects only the views of the author(s). The European Commission is not in any way responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. The information in this document is provided “as is”, and no guarantee or warranty is given that the information is fit for any particular purpose. The above referenced consortium members shall have no liability for damages of any kind including without limitation direct, special, indirect, or consequential damages that may result from the use of these materials subject to any liability which is mandatory due to applicable law. © 2020 by ARESIBO Consortium. Disclosure Statement The information contained in this document is the property of ARESIBO Consortium and it shall not be reproduced, disclosed, modified or communicated to any third parties without the prior written consent of the abovementioned entities. -

Hellenic Naval Academy Athens – Greece Invitation

HELLENIC NAVAL ACADEMY ATHENS – GREECE INVITATION TO MARITIME SECURITY COMMON MODULE (European initiative for the exchange of young military officers, inspired by Erasmus) Dear Colleagues, The Hellenic Naval Academy under the auspices of the European Security and Defence College, in the framework of the European initiative for the exchange of young military officers, inspired by Erasmus, has the honour to organise a “Maritime Security” Common Module. The module consists of an e-Learning part, as well as a residential session, that would be held in the Hellenic Naval Academy, from 23 to 27 April 2018, both parts being compulsory. The Module is based on the EMILYO Maritime Security Standard Curriculum. Its aim is to introduce the participants in the contemporary maritime security environment, and to familiarize them with Maritime Security Concepts. The Module will also provide a general knowledge of the European Union Maritime Security Strategy, its history and development, its main principles along with the challenges of its implementation. We would be pleased if you would accept this invitation and nominate suitable candidates for this training activity. For further details, regarding the course and administrative information, please refer to the attachments. Looking forward to welcoming European Cadets, Young Military and Coastguard Officers, during the residential phase of the “Maritime Security” Common Module. Attachments - Administrative information - Application form - Module presentation HELLENIC NAVAL ACADEMY ATHENS – GREECE MARITIME -

Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, California 93943-5138

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Compilations of Thesis Abstracts, from 2005 2005-03 Compilation of thesis abstracts, March 2005 http://hdl.handle.net/10945/27502 Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, California 93943-5138 NPS-09-05-002 Compilation of Theses Abstracts March 2005 Office of the Associate Provost and Dean of Research Naval Postgraduate School PREFACE This publication contains restricted abstracts (classified or restricted distribution) of theses submitted for the degrees Doctor of Philosophy, Master of Business Administration, Master of Science, and Master of Arts for the March 2005 graduation. Classified and restricted distribution abstracts are listed on the NPS SIPRnet. This compilation of abstracts of theses is published in order that those interested in the fields represented may have an opportunity to become acquainted with the nature and substance of the student research that has been undertaken. Copies of theses are available for those wishing more detailed information. The procedure for obtaining copies is outlined on the last page of this volume. For additional information on programs, or for a catalog, from the Naval Postgraduate School, contact the Director of Admissions. Director of Admissions Code 01B3 Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA 93943-5100 Phone: (831) 656-3093 Fax: (831) 656-3093 The World Wide Web edition of the School’s catalog is at: http://nps.navy.edu For further information about student and faculty research at the School, contact the Associate Provost and Dean -

AES 2005 Programme

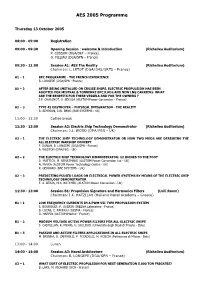

AES 2005 Programme Thursday 13 October 2005 08:00 - 09:00 Registration 09:00 - 09:30 Opening Session : welcome & introduction (Richelieu Auditorium) P. COSSON (DGA/DET – France) G. FILLIAU (DGA/SPN – France) 09:30 - 11:00 Session A1: AES The Reality (Richelieu Auditorium) Chairman: L. LETOT (DGA/D4S/SRTS – France) A1 – 1 BPC PROGRAMME - THE FRENCH EXPERIENCE B. LONGEPE (DGA/SPN - France) A1 – 2 AFTER BEING INSTALLED ON CRUISE SHIPS, ELECTRIC PROPULSION HAS BEEN ADOPTED FOR MISTRAL & TONNERRE BPC/LHDS AND NEW LNG CARRIERS. WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS FOR THESE VESSELS AND FOR THE OWNERS ? J.P. CHAIGNOT, V. SEKULA (ALSTOM Power Conversion - France) A1 – 3 TYPE 45 DESTROYER – PHYSICAL INTEGRATION - THE REALITY R. SIMPSON, J.W. BENG (BAE SYSTEMS - UK) 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee break 11:30 - 13:00 Session A2: Electric Ship Technology Demonstrator (Richelieu Auditorium) Chairman: J.L. WOOD (DPA/FBG – UK) A2 – 1 THE ELECTRIC SHIP TECHNOLOGY DEMONSTRATOR OR HOW TWO MODS ARE DERISKING THE ALL ELECTRIC WARSHIP CONCEPT F. DANAN, B. LONGEPE (DGA/SPN - France) A. WESTON (DPA/FBG - UK) A2 – 2 THE ELECTRIC SHIP TECHNOLOGY DEMONSTRATOR: 12 INCHES TO THE FOOT D. MATTICK, M. BENATMANE (ALSTOM Power Conversion Ltd - UK) N. McVEA (ALSTOM Power Technology Centre - UK) R. GERRARD (BAE SYSTEMS - UK) A2 – 3 PREDICTING PULSED LOADS ON ELECTRICAL POWER SYSTEMS BY MEANS OF THE ELECTRIC SHIP TECHNOLOGY DEMONSTRATOR E. A. LEWIS, M.S. BUTCHER (ALSTOM Power Conversion - UK) 11:30 - 13:00 Session B1: Propulsion Signature and Harmonics Filters (Lulli Room) Chairman: I.K. HATZILAU (Hellenic Naval Academy – Greece) B1 – 1 LOW FREQUENCY CURRENTS IN A PWM VSI TYPE PROPULSION SYSTEM S. -

Striving for Information Dominance

China’s Digital Destroyers: Striving for Information Dominance By Cindy Hurst Introduction In 1996, a Chinese academic military paper pointed out that the new military revolution is bound to have a crucial impact on naval warfare and the naval establishment. The article argued that information supremacy is the key to winning future naval warfare.1 Chinese government and military leaders, as well as scholars, have continued to encourage such a transition to a more informatized military. For example, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao stated that “We must actively promote the revolution in military affairs with Chinese characteristics and make efforts to achieve development by leaps and bounds in national defense and armed forces modernization.” He went on to say that modernization of the armed forces must be “dominated by informatization and based on mechanization.”2 According to China’s 2008 national defense white paper, informatization is the “strategic priority” of the country’s Navy modernization drive.3 While some critics perceive the modernization of China’s Navy as a threat, its modernization is viewed by the Chinese publicly as a defensive measure. The country has been growing at an average rate of eight percent annually over the past two decades. To support this growth, China needs raw and other materials, including oil and natural gas, metals, plastics, organic chemicals, electrical and other machinery, and optical and medical equipment. These resources are transported via ship from countries all over the 1 world. Due to piracy and instability in various regions of the world, without proper security, the safety of these shipments could be at risk. -

The People's Liberation Army's 37 Academic Institutions the People's

The People’s Liberation Army’s 37 Academic Institutions Kenneth Allen • Mingzhi Chen Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN: 9798635621417 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 Design by Heisey-Grove Design All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI Twitter: https://twitter.com/CASI_Research | @CASI_Research Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal, academic, or governmental use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete however, it is requested that reproductions credit the author and China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI). -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

49° IG Member (VTC) LoD 11 Subgroup International Naval Semester 02 February 2021 49° IG LoD 11 Group Members RANK FAMILY NAME FIRST NAME NATIONALITY INSTITUTION LtCdr MONDINO Samuele ITALIAN NAVAL ACADEMY Capt (N) Assoc. Prof. DIMITROV Nedko “NIKOLA VAPTSAROV” NAVAL ACADEMY RAMÍREZ ESPARZA LtCdr Gonzalo ESCUELA NAVAL MILITAR OTERO PhD GÓMEZ-PÉREZ Paula ESCUELA NAVAL MILITAR –VIGO UNIVERSITY Ass Prof KALLIGEROS Stamatios HELLENIC NAVAL ACADEMY Prof. PhD TEODORO Maria Filomena PORTUGUESE ESCOLA NAVAL MSc WYSOCKA Monika POLISH NAVAL ACADEMY Col. Assoc. Prof. PhD POPA Catalin “MIRCEA CEL BATRAN” NAVAL ACADEMY LoD 11 (INS) • Italian Naval Academy was authorized to be registered as EU organization and to take part to the Strategic Partnership. • ITNA has officially confirmed his participation to INS as partner. • Polish National Agency will provide last instructions needed to draft the Strategic Partnership agreement no later than the end of February 21 (all members confirmed their willing to present the S.P. during next 02/2022. • Romania, Poland and Italy has announced they will be ready to offer INS module since next 2022-2023 Academic years – (some Countries could offer their semester adherent to INS format since 22-23 A.A.). • Education material production: working group leaded by members; • Creation of temporary common platform to share material (textbook/lectures/lessons) during next week; STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP Done: • StratP Leader: PNA; • Partners: PL – BU – RO – PT – GR – IT (SP) To do: • Create the common platform; • Create wwgg