Environmental Circumscription and the Emergence of Social Complexity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of Pristine States

The Emergence of Pristine States Henri J. M. Claessen Leiden University ABSTRACT In this article the emergence of the Pristine State will be considered. First, I will present an overview of the applied method. Then seven cases of – probable – Pristine States are described. This makes a comparative research possible. As the case studies have been de- scribed with the help of the Complex Interaction Model, the com- parative part is also based upon this approach. From the compari- sons it appeared that all cases developed in a situation of relative wealth. They were not a consequence of hunger or population pres- sure. Nor could the often mentioned role of war be established as crucial in the formation of these states. War, as far as it occurred, was rather a consequence than a condition of state formation. 1. PRELIMINARY REMARKS In 1967, Morton H. Fried introduced the concept of the pristine state in The Evolution of Political Society, stating that ‘all contemporary states, even those that seem to be lineally descended from the states of high antiquity, like China, are really secondary states; the pristine states perished long ago’ (Fried 1967: 231). The pristine states were those that ‘emerged from stratified societies and experienced the slow, autochthonous growth of specialized formal instruments of social control out of their own needs for these institutions’ (Ibid.). The institutions grew and a leader – a priest, a warrior, a man- ager, or a charismatic person – came to the fore, and started to use his power. Gradually the organization of such a polity developed into an incipient early state (term in Claessen 1978, 2014). -

Carneiro's Social Circumscription Theory: Necessary but Not Sufficient

Carneiro's Social Circumscription Theory: Necessary but not Sufficient D. Blair Gibson El Camino College Firstly, let me state what an honor and delight it is to be asked to revisit one of the seminal contributions by a towering thinker of modern anthropology. Robert Carneiro's 1970 paper succeeded in weaving many of the strands of the cultural ecology and neo- evolutionism of the 1950s and 60s into a succinct theory of state origins. This theory in turn influenced and inspired many treat- ments having to do with the growth of complex societies, espe- cially those of the New World. His ‘reformulation’ represents the author's effort to reaffirm the basic tenets of the theory and estab- lish its applicability on a global scale. Carneiro starts his treatment with a summary of the past and present thinking on the origins of the state whereby he categorizes theories of state origins as either voluntaristic or coercive. By dint of these categories it has proven possible to discern a dichotomy in the underlying attitudes of those who have developed theories of social complexity, but these categories are not comprehensive and the examples that he provides are not all apt. The voluntaristic theories of yore presented chiefdoms and states as emerging to re- solve some structural problem such as the prevention of food scar- city or the provision of access to unequally distributed resources. To characterize Wittfogel's hydraulic hypothesis as a voluntaristic theory of state evolution is certainly problematic on two counts: Wittfogel was not so much concerned with explaining state origins as he was with detailing the character of the ‘hydraulic/apparatus’ state, and secondly, Wittfogel states that his theory includes ele- ments of coercion (Wittfogel 1957: 26). -

World-System-. and Evolution an Appraisal Professor Thoma-. D. Hall

World-System-. and Evolution An Appraisal Professor Thoma-. D. Hall Department of Sociology & Anthropology DcPauw University Grccnca-.tlc, IN 46135-0037 317-658-4519 internet : [email protected] Revised version of paper presented at the American Anthropological A-.sociation meeting, Nov. 16-19, 1995. Wa-.hington, D.C. Copyright 1996 by Thoma-. D. Hall. v. 7/8/96 ABSTRACT This paper makes six arguments. First, socio-cultural evolution must be studied from a "world-system" or intcrsocictal interact ion perspective. A focus on change in individual "societies" or "groups" fails to attend adequately to the effects of intcrsoci ctal interact ion on social and cultural change. Second, in order to be useful, theories of the modern world-system must be modified extensively to deal with non-capitali st settings. In particular, changes in system boundaries marked by exchange networks (for information , luxury or prestige goods, political/military interactions, and bulk goods) seldom coincide, and follow different patterns of change. Third, all such system-. tend to pulsat e, that is, expand and contract, or at lea-.t expand rapidly and less rapidly. Fourth, once hi erarchi cal forms of social organization develop such systems typically have cycles of rise and fall in the relative positions of constituent politics. Fifth, expansion of world-s ystems forms and transforms social relations in newly incorporate d area-.. While complex in the modern world-system, these changes arc even more complex in prccapitalist settings. Sixth, th ese two cycles combine with demographic and epidemiological processes to shape long -term socio-cultural evolution. Intro duction I begin by indicating several problems, then review recent develop ments in world-sy stem work, and end with some ways to promote more fruitful interact ion. -

Incentive Compatible Extraction Under Environmental Circumscription

The Origin of the State: Incentive Compatible Extraction under Environmental Circumscription David Schönholzer∗ April 10, 2017 Abstract Theories of early state formation posit that the state enabled an emerging elite to extract resources in exchange for protection from outside groups. This paper formalizes and empirically evaluates these forces in a unified framework. The model shows that extraction is closely linked to the idea of environmental circumscription: only if outside options are sufficiently poor for potential ex- tractees, (a) they are willing to accept extraction, and (b) extractors consider extraction capacity a worthwhile investment. In a global dataset of archaeo- logical sites on a grid with 184,523 cells, we then show that circumscription is strongly associated with the location of early states, using the intersection of large rivers through arid regions as an instrument. Our estimates suggest that extraction was more important in the Old World civilizations of Egypt and China while other motives such as protection were more important in the New World. ∗Department of Economics, UC Berkeley, [email protected]. I thank Ernesto Dal Bó, Brad DeLong, Frederico Finan, Edward Miguel, Gerard Roland, Raúl Sánchez de la Sierra, Joachim Voth and Noam Yuchtman for useful discussions and continuous encouragement as well as seminar participants in the BEHL Economic History Lunch at Berkeley, the Stanford Economic History conference, the Archaeology Brownbag Seminar at Berkeley and the Society for Ameri- can Archaeology 81st Conference session “Theoretical Approaches in Archaeology”. I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Fellowship number P1SKP1-158639. Word count: 10,044. -

Qt1sj9n878.Pdf

UC Riverside Cliodynamics Title Circumscription Theory of the Origins of the State: A Cross-Cultural Re- Analysis Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1sj9n878 Journal Cliodynamics, 7(2) Authors Zinkina, Julia Korotayev, Andrey Andreev, Alexey Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.21237/C7clio7232817 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Cliodynamics: The Journal of Quantitative History and Cultural Evolution Circumscription Theory of the Origins of the State: A Cross-Cultural Re-analysis Julia Zinkina1, Andrey Korotayev2,3, Alexey Andreev4 1 The Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration 2 National Research University Higher School of Economics 3 Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences 4 Moscow State University Abstract In the paper, we express some doubts about one of the assumptions of Robert Carneiro’s model on state (and chiefdom) formation, namely the role of circumscription. In our opinion, the main flaw of Carneiro’s original theory of state formation is that it implicitly assumes that every community dreamt to conquer its neighboring communities. We test the presence of various types of warfare (such as conquest warfare, land acquisition warfare, and plunder warfare) in societies with different degrees of political centralization. Quantitative cross-cultural tests reveal a rather strong correlation between political complexity and the presence of conquest warfare suggesting that conquest warfare was virtually absent among independent communities. Newer works by Carneiro propose a model explaining how simple chiefdoms could appear in the absence of conquest warfare. This model also includes circumscription, but our analysis suggests that it is unnecessary. -

5 Cultural Theories and Proximate-Level Explanations of Primitive War

5 Cultural Theories and Proximate-Level Explanations of Primitive War 5.1 Introduction Evolutionary theories (in the Darwinian sense) and ultimate-level explanations of the origin of war in hominid/human evolution, as reviewed in Ch. 4, have been proliferating ever since Darwin and, after the introduction of socio- biology, expecially in the last decades. In anthropology and the social sciences, however, the conception of primitive war as a social theme and cultural invention, and cultural-evolution theories of the origin of war have prevailed at least since Spencer, Tylor, Lubbock and other contemporaries of Darwin. I shall use the term ’cultural theories’ in this chapter - which has no more pretense than to give a reasonably adequate and complete review of the pertinent literature - as a convenient shorthand for all theories presented by such disciplines as cultural anthropology, ethnology, sociology, psychology, psychoanalysis, etc. By their very nature, many of these theories tend to focus on proximate-level explanations of primitive war causation and motivational analyses, and sometimes (seem to) preclude an evolutionary approach (in the Darwinian sense) altogether. Sometimes these theories are regarded as the sane alternative for the ’biological determinism’ and alleged ’innateness’ ascribed to the evolutionary theories. Yet, every theory, even the most anti-nativist one, does make implicit assumptions about universal human nature. The most common implicit assumption in the cultural theories is that the human being, by virtue of being a cultural animal, has severed all ties with organic evolution, and that ’biology’ (including phylogeny) is therefore quite irrelevant as an explanatory category. Human nature, in this conception, is equivalent to neonatal infinite behavioral plasticity (a tabula rasa) and subsequent cultural moulding; all behavior, including warring behavior, is essentially learned and modulated by the values and requirements of the socio- cultural milieu. -

Political Anthropology (SOAN3101)

Political Anthropology (SOAN3101) CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Chapter Introduction The chapter begins by imparting preliminary knowledge about what anthropology as a science means, the subject matter of anthropology in general and social anthropology in particular. This chapter also devotes itself to the discussion of the branches of anthropology, guiding principles in anthropology and nature of research in the discipline. Finally, it concludes by defining political anthropology as sub field of political anthropology. 1.2 Anthropology: A general Introduction I. Anthropology Defined Anthropology is the holistic and scientific study of humankind. As such, it is a very broad field that includes human biology, genetics and evolution; the study of human history, prehistory, and archaeology; human culture, cultural patterns, and cultural diversity; social structure, kinship, economics, religion, politics, art, and linguistics (the scientific study of language). What Does THAT Mean? ⚫ Anthropology has four main parts • Physical or biological anthropology • Archaeology • Cultural (and social) anthropology • Linguistics ⚫ VERY BROAD FIELD • Runs the scope from medicine and genetics (pure or hard sciences) to art, religion, drama, and poetry (humanities) • Something for everyone Wollo University 2020 Page 1 Political Anthropology (SOAN3101) II. The Subfields of Anthropology in More Detail A. Physical Anthropology ⚫ Physical anthropology (also known as biological anthropology) is the study of human biological diversity and evolution. ⚫ Includes: • Medical anthropology • Pale o-anthropology (including some paleontology) • Human genetics and evolution • Primatology B. Archaeology ⚫ The study of human prehistory and cultural evolution (no dinosaurs) ⚫ Archaeologists study ancient society and culture through material remains ➢ Like artifacts and human remains ⚫ Bioarchaeology = study of ancient human remains ➢ Paleopathology – study of ancient disease through materials remains C. -

Tesi Pubblicata.Indb

An interdisciplinary analysis on the state formation and kingship in the Predynastic Egypt Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Paolo Medici Berlin 2020 Erstgutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jochem Kahl Zweitgutachter: PD Dr. Jan Moje Tag der Disputation: 10 Dezember 2019 INDEX Introduction ......................................................................................6 Defi nitions of ‘evolution’ and ‘development’ ........................................6 PART 1: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ..................................................8 1.1 The theories and studies on state formation and the development of social complexity: from the origins to modern period. ................9 1.1.1 Introduction ............................................................................9 1.1.2 The fi rst studies .......................................................................9 The period before the nineteenth century .......................................10 1.1.3 From the nineteenth century to the 1970s .................................14 Lewis Henry Morgan and Karl Marx, the fi rst theories ......................14 The legacy of Karl Marx – Engels’ studies .......................................15 The Austria-German intellectuals ...................................................19 The evolutionary approach and the renaissance of the social studies. .22 1.2 The theories and studies on the state formation and social complexity -

The Origin of the State: Land Productivity Or Appropriability?*

The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability? Joram Mayshary Omer Moavz Luigi Pascalix November 6, 2020 Abstract The conventional theory about the origin of the state is that the adoption of farming increased land productivity, which led to the formation of food surplus. This surplus was a prerequisite for the emergence of tax-levying elites, and eventually states. We challenge this theory and propose that hierarchy arose due to the shift to dependence on appropriable cereal grains. Our empirical investigation, utilizing multiple data sets spanning several millennia, demonstrates a causal e¤ect of the cultivation of cereals on hierarchy, without …nding a similar e¤ect for land productivity. We further support our claims with several case studies. Geography, Hierarchy, Institutions, State Capacity JEL Classification Numbers: D02, D82, H10, O43 We would like to thank Daron Acemoglu, Alberto Alesina, Yakov Amihud, Josh Angrist, Quamrul Ashraf, David Atkin, Simcha Barkai, Sascha Becker, Davide Cantoni, Ernesto Dal Bo, Carl-Johan Dalgaard, Diana Egerton- Warburton, James Fenske, Raquel Fernandez, Oded Galor, Eric Ginder, Paola Giuliano, Stephen Haber, Naomi Hausman, Victor Lavy, Andrea Matranga, Stelios Michalopoulos, Joel Mokir, Suresh Naidu, Nathan Nunn, Omer Ozak, Joel Slemrod, Fabio Schiantarelli, James Snyder, Uwe Sunde, Jim Robinson, Yona Rubinstein, Ana Tur Prats, Felipe Valencia, Tom Vogl, Joachim Voth, John Wallis and David Weil for useful comments. We are also grateful for comments from participants in many seminars and workshops. yDepartment of Economics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Email: [email protected] zDepartment of Economics University of Warwick, School of Economics Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, CAGE and CEPR. -

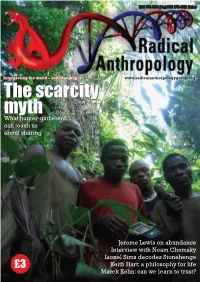

The Scarcity Myth the Scarcity Myth

Issue 2: 2008/9 ISSN 1756-0896 (Print)/ISSN 1756-090X (Online) Intterrprettiing tthe wwoorlldd – and changgiinngg iitt wwwwww..radiicallantthropollooggyyggrroouupp..oorrgg TThhee ssccaarrcciittyy mWmhatyyhuntttehh r-gatherers caan teachh us about sharriing Jerome Lewis on abundance Interview with Noam Chomsky Lionel Sims decodes Stonehenge £3 Keith Hart: a philosophy for life Marek Kohn: can we learn to trust? Editor: Stuart Watkins Email: [email protected] Who we are and what we do Editorial Board: Radical Anthropology is the journal of course at Morley College, London, was Kevin Brown , political activist. the Radical Anthropology Group. closed down, supposedly for budgetary Elena Fejdiova , social reasons. Within a few weeks, the anthropologist. Radical: about the inherent, students got organised, electing a Dave Flynn, trade unionist and fundamental roots of an issue. treasurer, secretary and other officers. political activist. Anthropology: the scientific study of the They booked a library in Camden – and Chris Knight , professor of origin, behaviour, and physical, social, invited Chris to continue teaching next anthropology at the University and cultural development of humans. year. In this way, the Radical of East London. Anthropology Group was born. Eleanor Leone , MA Social Anthropology asks one big question: Anthropology student what does it mean to be human? To Later, Lionel Sims, who since the 1960s at Goldsmiths College, answer this, we cannot rely on common had been lecturing in sociology at the University of London. sense or on philosophical arguments. We University of East London, came across Jerome Lewis , anthropologist must study how humans actually live – Chris’s PhD on human origins and – at University College London. -

The Circumscription Theory: a Clarification, Amplification, and Reformulation

The Circumscription Theory: A Clarification, Amplification, and Reformulation Robert L. Carneiro American Museum of Natural History In 1963 in his book Social Anthropology, Paul Bohannan wrote: ‘we know that we cannot answer questions about the “origin” of the state because the factual evidence is buried deep in the unre- corded past’ (Bohannan 1963: 271). Today, though, half a century later, neither Bohannan nor anyone else would be inclined to utter these words. * * * The emergence of the state was an event of such importance in the history of the mankind that it has long commanded the atten- tion of historians and social scientists alike. And the event has been looked at in at least two contrasting ways. Some observers have considered the rise of the state to be such a singular occurrence that only a very special set of circumstances could have brought it about. The 19th century sociologist Lester F. Ward, for example, was convinced that the creation of the state was so remarkable that it must have been ‘the result of an extraordinary exercise of the ra- tional faculty’. Indeed, so exceptional did he regard it that he in- sisted ‘it must have been the emanation of a single brain or a few concerting minds’ (Ward 1883: 224). Akin to this view – if not quite so extreme – is the belief that the origin of the state, while, perhaps, not a unique event, was at least a very rare one. It took (it is argued) an unusual – even a for- tuitous – set of circumstances to bring it about. Associated with this belief is the notion that no matter how many independent cases of state formation there might have been, each one was substan- tially different from the rest. -

Warfare and the Evolution of Social Complexity: a Multilevel-Selection Approach

UC Irvine Structure and Dynamics Title Warfare and the Evolution of Social Complexity: A Multilevel-Selection Approach Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7j11945r Journal Structure and Dynamics, 4(3) Author Turchin, Peter Publication Date 2010-11-07 DOI 10.5070/SD943003313 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Turchin: Warfare and Social Complexity Warfare and the Evolution of Social Complexity: A Multilevel-Selection Approach Peter Turchin University of Connecticut e-mail: [email protected] Final version: 17 January 2011 Summary Multilevel selection is a powerful theoretical framework for understanding how complex hierarchical systems evolve by iteratively adding control levels. Here I apply this framework to a major transition in human social evolution, from small-scale egalitarian groups to large-scale hierarchical societies such as states and empires. A major mathematical result in multilevel selection, the Price equation, specifies the conditions concerning the structure of cultural variation and selective pressures that promote evolution of larger-scale societies. Specifically, large states should arise in regions where culturally very different people are in contact, and where interpolity competition – warfare – is particularly intense. For the period of human history from the Axial Age to the Age of Discovery (c.500 BCE–1500 CE), conditions particularly favorable for the rise of large empires obtained on steppe frontiers, contact regions between nomadic pastoralists and settled agriculturalists. An empirical investigation of warfare lethality, focusing on the fates of populations of conquered cities, indicates that genocide was an order of magnitude more frequent in steppe- frontier wars than in wars between culturally similar groups.