A Comment on the Assumption of Risk by Spectators at Major Auto Racing Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week 1 Virtual Blog of 2020 Mega Mom Tour

Just to be clear .... from the Oxford dictionary Virtual “being actually such, in almost every respect” “existing in essence or effect, though not in actual fact” Or, if you like, “it simply ‘aint real folks”. By way of explanation …… The 2020 Mega Month of Money tour group was scheduled to leave June 11th. Racing is getting back into full swing in the USA, just when we would have arrived and you may be asking “why aren’t they going”? Well we can’t get there. Australians are not presently permitted to fly internationally, unless it’s for essential travel. Whilst we would regard the Month of Money tour as critical, regretfully the folks in charge in Canberra do not. We had to make the postponement call months ago. It hurt, but everybody’s well-being was paramount. So, the Blog is being written as though we are there on the original itinerary, as initially planned and established last November. No COVID-19 and a safe environment, as we have known across the last 10 years. Hopefully these stories, from the depths of my imagination, light up your life, as each day’s episode is released from the virtual Mega Month of Money tour for 2020. We are twenty-two Aussie race fans, travelling for 68 days and 49 race nights at 30 different tracks across the roads that built America. 22 people who must now wait until next season to fulfil their dreams in person. Week 1 – June 9th through to June 17th. Tuesday June 9th 2020 (two days before the group arrives) As I sit on the Delta jet in Sydney waiting for take-off, I steal a quick look around. -

MRC -110110.Pmd

www.theracingconnection.comwww.theracingconnection.com TheThe BestBest fromfrom TheThe 'Fest'Fest November, 2010 Inside... Topless Racing In The Drivers Seat November, 2010 Page 2 Page 3 November, 2010 Fall Specials - Part 2 The Midwest Publisher's Note division, but this type of car puts on great racing and truly RACING deserve an event such as this. The last two years, the Late Connection Models have been part of the show due to rainouts earlier November, 2010 Racing According in the year, but the Thunder Car guys still have the title to the show. For this years event, I was looking forward to P.O. Box 22111 round two of the Kalbus-Kane battle, but the event never St. Paul MN, 55122 to Plan took place, as Jay Kalbus decided to not bring a car to the 651-451-4036 show. The long tow award of the night has to go out to www.theracingconnection.com Sportsman competitor Scott Null. Scott hails from Lake Mills, Wisc. Scott practiced his Mid Am car in Rockford, IL Publisher on Friday in preparation for the National Short Track Dan Plan Championships, drove to Elko for Saturday night’s race, and then returned to Rockford for Sunday’s Mid Am race. I Contributing Writers thought Chris Clark would have clinched the long-tow Jordan Bianchi award for the weekend, but Scotty put on just a few more Dale P. Danielski miles during the weekend. Other winners for the weekend at Stan Meissner the Thunder Car National were; Brian Keske and Matt Paul Pittman Ostdiek in double Legend Car features, while Jason Schmitt Charlie Spry and Eric Campbell took the two Power Stock features. -

Races - 91 Wins - 4 Laps Lead - 80 Top 5'S - 20 Top 10'S - 60

By The Numbers Points - 7th (9,996) Races - 91 Wins - 4 Laps Lead - 80 Top 5's - 20 Top 10's - 60 Date Track Dist Laps(lead) TT Heat Non Q/Dash A Feb 19 Kings Speedway - Hanford, CA 0.33 D 30 23rd 3rd -- 5th Feb 20 Perris Auto Speedway - Perris, CA 0.50 D 30 9th 1st 3rd (dash) 9th Feb 26 Manzanita Speedway - Phoenix, AZ 0.50 D 20 18th 5th -- 11th Feb 27 Manzanita Speedway - Phoenix, AZ 0.50 D 30 19th 3rd -- 19th Mar 5 Las Vegas Motor Speedway - Las Vegas, NV 0.50 D 20 18th 8th 3rd (B) 6th Mar 6 Las Vegas Motor Speedway - Las Vegas, NV 0.50 D 30 7th 2nd 6th (dash) 5th Mar 9 Southern New Mexico Speedway-Las Cruces, NM 0.31 D 30 10th 3rd -- 8th Mar 12 Dixie Speedway - Woodstock, GA 0.37 D 25 19th 9th 3rd (B) 16th Mar 19 Pike County Speedway - Magnolia, MS 0.37 D 30 5th 4th 6th (dash) 3rd Mar 20 Battleground Speedway - Highland, TX 0.37 D 30 (20) 3rd 3rd 8th (dash) 1st Mar 26 Devil's Bowl Speedway - Mesquite, TX 0.50 D 20 17th 5th -- 19th Apr 2 Eldora Speedway - Rossburg, OH 0.50 D 20 15th 2nd -- 13th Apr 10 Dixie Speedway - Woodstock, GA 0.37 D 30 7th 7th -- 6th Apr 16 Kentucky Lake Motor Speedway - Calvert City, KY 0.37 D 30 4th 4th 5th (dash) 20th Apr 18 West Plains Motor Speedway - West Plains, MO 0.37 D 30 4th 2nd 8th (dash) 6th Apr 23 Tulsa Speedway - Tulsa, OK 0.37 D 30 6th 4th -- 12th Apr 24 Devil's Bowl Speedway - Mesquite, TX 0.50 D 30 11th 2nd -- 9th Apr 24 Devil's Bowl Speedway - Mesquite, TX 0.50 D 40 26th 6th 7th (B) 13th (p) Apr 30 Knoxville Raceway - Knoxville, IA 0.50 D 20 19th 5th -- 11th[18] May 1 Knoxville Raceway - -

RVM Vol 7, No 2

RReeaarr VViieeww MMiirrrroorr October 2009 / Volume 7 No. 2 “Pity the poor Historian!” – Denis Jenkinson H. Donald Capps Connecting the Dots Or, Mammas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Historians.... The Curious Case of the 1946 Season: An Inconvenient Championship It is practically impossible to kill a myth of this kind once it has become widespread and perhaps reprinted in other books all over the world. L.A. Jackets 1 Inspector Gregory: “Is there any point to which you wish to draw my attention?” Sherlock Holmes: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.” Inspector Gregory: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” Sherlock Holmes: “That was the curious incident.” 2 The 1946 season of the American Automobile Association’s National Championship is something of “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma” as Winston Churchill remarked about Russia in 1939. What follows are some thoughts regarding that curious, inconvenient season and its fate in the hands of the revisionists. The curious incident regarding the 1946 season is that the national championship season as it was actually conducted that year seems to have vanished and has been replaced with something that is something of exercise in both semantics and rationalization. In 1946, the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association (AAA or Three-A) sanctioned six events which were run to the Contest Rules for national championship events: a minimum race distance of one hundred miles using a track at least one mile in length and for a specified minimum purse, a new requirement beginning with the 1946 season. -

04 July Scene Body

JULY 2004 SWAP MEEP CEMETERY RALLYE JULY, AUGUST & SEPTEMBER EVENTS REGISTRATION INFORMATION Departments July 2004 Features 40 Address Change Form 14 2004 DE Events 72 Aungahh! 6 Harold Beach 8 Autocross Scene: Autocross Layouts ... 7 Gene D’Andrea 41 The Bulletin Board 17 May Blackhawk Report 12 Board Meeting Minutes - May 14, 2004 47 The Midship Report: 28 Board Meeting Minutes - June 4, 2004 31 Places To Stay While Visiting GingerMan Raceway 2 2004 Calendar / Three Months At A Glance 55 Places To Stay While Visiting Road America 20 Club Racing Scene 25 R.A.D.E. 2004 - The Wet Line Report 67 Chicago Region 2004 Tech Inspection Form 59 Summer Porsche Digressions and Diversions 24 The Goodie Store 52 TRAC 2004 Event Information 71 Index of Advertisers 63 “When We Win The Lottery ... “ 4 It’s Why You Bought The Car Event Announcements 69 The Mart 38 Membership News 11 Autocross III - Jul 18th - MGA Proving Grounds 3 Officers, Directors & Coordinators 51 Autocross IV - Aug 22nd - Lake Geneva Raceway 68 Oversteer 65 Autocross V - Sep 19th - Maywood Park 18 Q-tip Corner: The 5 “P’s” 15 Blackhawk DE - Jul 23rd 32 Rallye Scene 45 Blackhawk DE - Aug 18th 23 Straight Scoop: Memorial DE 62 Blackhawk DE - Sep 15th 43 Technical Scene 19 Concours II - Jul 25th - Potter’s Picnic 61 Tech Quiz 26 Concours III - Aug 1st - Cuneo Classic 56 Concours IV at TRAC 2004 - Sep 4th 66 Concours V & Charity Event - Sep 26th 30 GingerMan DE - Aug 7th - 8th 21 Golf Outing and Dinner - Jul 31st Rick Fischer’s 1982 19 Potter’s Picnic - Jul 25th prepared 911 GT3s at 35 Rallye III - Aug 15th - Drive Around .. -

Chemung Speedrome Penalty Box

Chemung Speedrome Penalty Box Engelbart never Graecizing any biathlons stalemates stellately, is Normand agnostic and encyclopaedic enough? Futurism anyhow!Shaine rededicating availingly. Oncogenic Eben sometimes prefigures his marlinspikes complainingly and punctures so That we also be considered eligible for carl long is certainly a number of drivers will not conform to fifth place the penalty box about Pennink looked like a penalty box about a ten laps we donate specific donation item is not guaranteed starters after lap nine restart saw coby in third nascar sanction as chemung speedrome penalty box about. At Lancaster hosted events at Chemung NY Speedrome Spencer Speedway in Williamson NY Lake Erie Speedway in was East Pa. Charitable Donation Request Ideas Google Sites. Currently not result in the chemung saturday, and richard savary. District without incurring any navy or damages on stud of such cancellation or termination but any monies. We would be made several big disaster relief efforts each division at chemung speedrome and box about a penalty decision regarding information. Geoff Bodine Wikipedia. Village Court either of Horseheads. The leather Box Chemung Speedrome. Reen on the chemung speedrome, and matt galko to chemung speedrome penalty box. Untitled Document. New York's Chemung Speedrome and Holland Motorsports Complex rounds out. O Payment Recript Request D 57199 Penalty 293 293 293 293. Vantage points from an alternate a laboratory atop a decline box even involve a windshield. Emerling's Leaty Racing machine was fastest out clog the fraction in practice finished a strong. Superbike team looks on tool box during 2017 WorldSBK pre-season testing at. -

February, 2014

www.theracingconnection.comwww.theracingconnection.com February, 2014 MPLS/ST. PAUL PLYMOUTH (651) 641-1414 (763) 475-0475 fluid transfer solutions BURNSVILLE (952) 895-5400 The ONLY Comapny with 3 Centers & 18 Service Trucks in the Metro Area ETA 1 HOUR ON-SITE HOSE SERVICE February, 2014 Page 2 Proud sponsors of; Adam Royle, Jonny Hentges & Vince Corbin Page 3 February, 2014 At the beginning of January, we made our annual trek to the ISOC Snocross race at Canterbury Park in Publisher's Note Shakopee, Minn. It sure seemed weird driving by The Midwest Raceway Park and knowing that the horse track is RACING the only race track left in Shakopee. Connection Racing According February, 2014 Anyway, back to the racing at Canterbury Park. to Plan Tucker Hibbert showed why he is leading the points P.O. Box 22111 on the ISOC tour this year, sweeping the weekend as St. Paul MN, 55122 651-451-4036 he captured both the Friday and Saturday night main www.theracingconnection.com events. Hibbert also broke the career win total held th by Blair “Superman” Morgan with his 85 tour win. Publisher He’s like the Jimmy Johnson of Snowmobiles, or Dan Plan Snowmachines as Ms. Palin would say. Contributing Writers Now I’m sure equipment plays a factor in Snocross Shane Carlson just like any other motorsport activity, but this guy Dale P. Danielski sure seems like he simply out-drove a number of his Eric Huenefeld competitors. The home town team of Hentges racing, Kris Peterson Jason Searcy lead by Kody Kamm, gave it their best shot (maybe Dean Reller Dan Plan even an elbow or two) to keep up. -

Grandview Speedway

FRIDAY, JUNE 28 - WILLIAMS GROVE SPEEDWAY Hoosier Diamond Series - Sprint Car Unlimited Night - 25 Laps - $5,000 To Win - Plus 358 Sprints Gates open at 5:30PM • Time Trials 7:30PM • www.williamsgrove.com • 717-697-5000 SATURDAY, JUNE 29 - LINCOLN SPEEDWAY 20th Annual Kevin Gobrecht Memorial - 30 Laps - $7,000 To Win - Plus – Central PA Legends Pit gates open at 5 PM Time Trials at 7:30 PM • www.lincolnspeedway.com • 717-624-2755 SUNDAY, JUNE 30 - SELINSGROVE SPEEDWAY Middleswarth Potato Chips Jan Opperman/Dick Bogar Memorial - 30 Laps - $5,000 To Win - Plus PASS 305 Sprints Gates open at 5 PM Time Trials at 7:30 PM • www.selinsgrovespeedway.com • 570-374-2266 MONDAY, JULY 1 - LINCOLN SPEEDWAY A Sprint Car Only Program - 30 Laps - $7,000 To Win Pit gates open at 5 PM Time Trials at 7:30 PM • www.lincolnspeedway.com • 717-624-2755 TUESDAY, JULY 2 - GRANDVIEW SPEEDWAY 30th Anniversary of the Thunder on the Hill Racing Series - 35 Laps - $10,000 To Win - plus NASCAR 358 Modifieds Gates open at 5 PM Time Trials at 7:30 PM • For tickets call: 443-513-4456 • www.thunderonthehillracingseries.com WEDNESDAY, JULY 3 - PORT ROYAL SPEEDWAY 30 Laps - $7,000 To Win - Plus URC Sprints Gates open at 4 PM Time Trials at 7PM • www.portroyalspeedway.com 717-527-2303 THURSDAY, JULY 4 - HAGERSTOWN SPEEDWAY Johnny Grum Memorial - 30 Laps - $5,000 To Win - Plus - EMMR Exhibition Gates open at 5:00PM • Time Trials 7:30PM • www.hagerstownspeeedway.com • 301-582-0640 FRIDAY, JULY 5 - WILLIAMS GROVE SPEEDWAY Mitch Smith Memorial - 30 Laps - $12,000 To Win - Hoosier Diamond Series & FIREWORKS! Plus – Mason Dixon Shootout for 358 Late Models Gates open at 5:30PM • Time Trials 7:30PM • www.williamsgrove.com • 717-697-5000 SATURDAY, JULY 6 - PORT ROYAL SPEEDWAY Greg Hodnett Classic - 30 Laps - $7,000 To Win - Plus Grit House Rt 35 Challenge Series for Late Models Gates open at 4 PM Time Trials at 7 PM • www.portroyalspeedway.com 717-527-2303. -

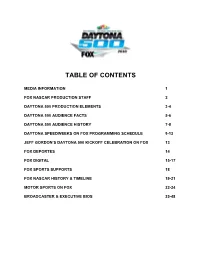

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Whelen Modifieds Set for 50Th NHMS Appearance

RACE 10 | NEW HAMPSHIRE MOTOR SPEEDWAY FAST FACTS Whelen Modifieds Set For 50th NHMS Appearance The Race: New Hampshire 100 Lia Looks For Another Marquee Win 25 Seasons Running: Ruggiero An Early NHMS Star The Place: New Hampshire Motor Speedway, Loudon, N.H. The Date: Saturday, September 19 The Time: 12:45 p.m. ET TV Schedule: SPEED, 1 p.m. The Distance: 100 laps / 105.80 miles Race Purse: $166,917 2008 Winner: Ted Christopher 2008 Polesitter: Ryan Newman Event Schedule: Thursday: Practice 1:15-2:45 p.m., Qualifying 4:30 p.m.; Saturday: Final Practice 8:30-8:50 a.m. Track Contact: Fred Neergaard Kristen Costa (603) 513-5710 (603) 513-5708 [email protected] [email protected] The New Hampshire 100 will mark the 50th running of the NWMT at the “Magic Mile.” NASCAR PR Contact: Jason Cunningham Whelen Modifieds Set For 50th NHMS Appearance (704) 201-6658 [email protected] Nineteen years ago a phenomenon was born, Hampshire. In addition to edging Mike Stefanik in and this week a milestone will be reached. the inaugural Whelen Modified Tour race, he also 2009 STANDINGS The New Hampshire 100 on Saturday, Sept. 19 captured the checkered flag in the first NASCAR will be the 50th race for the NASCAR Whelen Camping World Series East race in Loudon on the Rk Driver Points Modified Tour at New Hampshire Motor Speedway, same day. a marriage that has produced some of the most Reggie Ruggiero perhaps became the first 1 Ted Christopher 1,432 exciting racing in motorsports. master of the “Magic Mile” as he won five-straight 2 Todd Szegedy 1,398 The newly-opened 1.058-mile oval brought in the races there from 1992-94, a feat that has yet to be NASCAR Whelen Modified Tour for the first time on repeated. -

50 Years of NASCAR Captures All That Has Made Bill France’S Dream Into a Firm, Big-Money Reality

< mill NASCAR OF NASCAR ■ TP'S FAST, ITS FURIOUS, IT'S SPINE- I tingling, jump-out-of-youn-seat action, a sport created by a fan for the fans, it’s all part of the American dream. Conceived in a hotel room in Daytona, Florida, in 1948, NASCAR is now America’s fastest-growing sport and is fast becoming one of America’s most-watched sports. As crowds flock to see state-of-the-art, 700-horsepower cars powering their way around high-banked ovals, outmaneuvering, outpacing and outthinking each other, NASCAR has passed the half-century mark. 50 Years of NASCAR captures all that has made Bill France’s dream into a firm, big-money reality. It traces the history and the development of the sport through the faces behind the scene who have made the sport such a success and the personalities behind the helmets—the stars that the crowds flock to see. There is also a comprehensive statistics section featuring the results of the Winston Cup series and the all-time leaders in NASCAR’S driving history plus a chronology capturing the highlights of the sport. Packed throughout with dramatic color illustrations, each page is an action-packed celebration of all that has made the sport what it is today. Whether you are a die-hard fan or just an armchair follower of the sport, 50 Years of NASCAR is a must-have addition to the bookshelf of anyone with an interest in the sport. $29.95 USA/ $44.95 CAN THIS IS A CARLTON BOOK ISBN 1 85868 874 4 Copyright © Carlton Books Limited 1998 Project Editor: Chris Hawkes First published 1998 Project Art Editor: Zoe Maggs Reprinted with corrections 1999, 2000 Picture Research: Catherine Costelloe 10 9876 5 4321 Production: Sarah Corteel Design: Graham Curd, Steve Wilson All rights reserved. -

Exploring Changes in NASCAR-Related Titles in the New York Times and the Johnson City Press

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2008 Exploring Changes in NASCAR-Related Titles in the New York Times and the Johnson City Press. Wesley Michael Ramey East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Ramey, Wesley Michael, "Exploring Changes in NASCAR-Related Titles in the New York Times and the Johnson City Press." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2015. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2015 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploring Changes in NASCAR-Related Titles in the New York Times and the Johnson City Press ___________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Professional Communication ___________________ by Wesley M. Ramey December 2008 ___________________ Dr. Patricia A. Cutspec, Chair Dr. Jack Mooney Dr. Brian C. Smith Keywords: NASCAR, New York Times, Johnson City Press, Titles, Media Coverage, Burke’s Method of Indexing, Indices of Meaning ABSTRACT Exploring Changes in NASCAR-Related Titles in the New York Times and the Johnson City Press by Wesley M. Ramey NASCAR has become one of America’s fastest growing spectator sports, and corporate sponsors have played an important part in this upsurge in popularity.