Dace Ruklisa for Edit- Ing This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture | the AHRC Cultural Value

Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska 2 Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska THE AHRC CULTURAL VALUE PROJECT CONTENTS Foreword 3 4. The engaged citizen: civic agency 58 & civic engagement Executive summary 6 Preconditions for political engagement 59 Civic space and civic engagement: three case studies 61 Part 1 Introduction Creative challenge: cultural industries, digging 63 and climate change 1. Rethinking the terms of the cultural 12 Culture, conflict and post-conflict: 66 value debate a double-edged sword? The Cultural Value Project 12 Culture and art: a brief intellectual history 14 5. Communities, Regeneration and Space 71 Cultural policy and the many lives of cultural value 16 Place, identity and public art 71 Beyond dichotomies: the view from 19 Urban regeneration 74 Cultural Value Project awards Creative places, creative quarters 77 Prioritising experience and methodological diversity 21 Community arts 81 Coda: arts, culture and rural communities 83 2. Cross-cutting themes 25 Modes of cultural engagement 25 6. Economy: impact, innovation and ecology 86 Arts and culture in an unequal society 29 The economic benefits of what? 87 Digital transformations 34 Ways of counting 89 Wellbeing and capabilities 37 Agglomeration and attractiveness 91 The innovation economy 92 Part 2 Components of Cultural Value Ecologies of culture 95 3. The reflective individual 42 7. Health, ageing and wellbeing 100 Cultural engagement and the self 43 Therapeutic, clinical and environmental 101 Case study: arts, culture and the criminal 47 interventions justice system Community-based arts and health 104 Cultural engagement and the other 49 Longer-term health benefits and subjective 106 Case study: professional and informal carers 51 wellbeing Culture and international influence 54 Ageing and dementia 108 Two cultures? 110 8. -

Programme Spring 2009

spring concert 2009 wolfgang amadeus mozart overture: don giovanni clarinet concerto in A requiem in D minor conductor: Andrew Rochford saturday 28 march, 2009 ´09 7.30pm Programme £10 welcome Dear audience How time flies when you are having fun! We find it hard to believe it is 10 years since the Royal Free Music Society was founded as an independent music society having originated in the Royal Free Medical School Music Society. Throughout that time a number of key elements have sustained the Society in its core activity of good quality amateur music making. Firstly, we have been fortunate to have the support and guidance of a number of outstanding musical directors, most notably Andrew Rochford, our conductor tonight. Andrew has been the guiding light of the Society giving up huge amounts of time in what is a very busy life and we are immensely grateful for his time, patience, skill and knowledge. We have also been most fortunate in maintaining our links with the Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust who provide us with free rehearsal space each week. Thirdly has been our enduring and most enjoyable relationship with St. Mark’s Church and its parish that allow us to perform in this magnificent venue regularly. We thank both communities for their continued support. In recent years we have been delighted to see our sister organization, the Hampstead Sinfonietta, develop. This talented group of musicians not only accompanies us in the great choral works but has also provided a wide and varied repertoire of orchestral music in recent years. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Download Publication

(~2C i ~c Co P / The Arts Council of Great Britai n Twenty fourth The Arts Council of Great Britai n s 105 Piccadilly annual report and account London W1 V OA U year ended 31 March 1969 01-629949 5 ARTS COUNCIL OF GREAT BRITAIN REFERENCE ONLY DO NOT REMOVE . FROM THE LIBRA] Membership of the council, committees and panels Council The Lord Goodman (Chairman ) Professor Sir William Coldstream, CBE, DLitt (Vice-Chairman ) The Hon . Michael Asto r Frederic R . Cox, OB E Colonel William Crawshay, DSO, T D Miss Constance Cumming s Cedric Thorpe Davie, OBE, LL D Peter Hall, CB E The Earl of Harewoo d Hugh Jenkins, M P Professor Frank Kermod e J. W. Lambert, DSC Sir Joseph Lockwoo d Colin H. Mackenzie, CMG DrAlun Oldfield-Davies, CB E John Pope-Hennessy, CB E The Hon . Sir Leslie Scarman, OB E George Singleton, CB E Sir John Witt Scottish Arts Counci l Colin H. Mackenzie, CMG (Chairman ) George Singleton, CBE (Vice-Chairman ) Neill Aitke n J . S . Boyl e Colin Chandler J. B . Dalby, OB E Cedric Thorpe Davie, OBE, LL D Professor T . A. Dun n David A . Donaldson, RSA, R P The Earl Haig, OB E Douglas Hall, FM A Clifford Hanley William Hannan, M P R . D . Hunter, MB E Ronald Macdonald Neil Paterso n Alan Reiach, OB E Professor D . Talbot Rice, CBE, TD, DLitt, FS A Dame Jean Roberts, DBE, DL, J P Alan Roger Ivison S . Wheatley Thomas Wilso n Welsh Arts Counci l Colonel William Crawshay, DSO, TD (Chairman ) Alex J . -

December 2017

International Ernest Bloch Society President Steven Isserlis CBE Associate musicians: Natalie Clein, Danny Driver, Rivka Golani, Jack Liebeck, Malcolm Singer Raphael Wallfisch, Benjamin Wolf, News Sheet no 1 – December 2017 Ernest Bloch Studies Further to the successful publication of Ernest Bloch Studies by Cambridge University Press, and its launch at SOAS in October, hosted jointly by JMI and The Spiro Ark, the International Ernest Bloch Society has once more sprung in to action. Ernest Bloch, who left his native Switzerland to settle in the United States in 1916 was one of the great twentieth-century composers. He was influenced by a range of genres and styles - Jewish, American and Swiss - and his works reflect his lifelong struggle with his identity. Drawing on first- hand recollections of relatives and others who knew and worked with the composer, this collection is the most comprehensive study to date of Bloch's life, musical achievement and reception. Contributors present the latest research on Bloch's works and compositional practice, including studies of his Avodath Hakodesh (Sacred Service), violin pieces such as Nigun, the symphonic Schelomo, and the opera Macbeth. Setting the quality and significance of Bloch's output in its historical and cultural contexts, this book provides scholarly analyses as well as a full chronology, list of online resources, catalogue of published and unpublished works, and selected further reading. It is available via Amazon. The book was inspired by the International Conference that the Society held at Cambridge University in 2007. You can read reports and see pictures from the 2007 International Conference on the International Ernest Bloch Society website here: http://ernestblochsociety.org/index.php?id=bloch-jubilee-international-conference Bloch in Britain – a talk by Alex Knapp and Norman Solomon, 22 February. -

London Group Events

UCL ALUMNI LONDON GROUP London January – June Group 2020 Events Dear Fellow Alumni, UCL Alumni London I am writing this first introduction to our program of Group Events, events as your new Chair of the UCL London Alumni July – December 2019 Organising Team. I am pleased and proud to accept this role and after many years of enjoying events organised by the Team I am now in a position to pay back. Firstly Theatre: Noises Off though I must pay the highest tribute to my predecessor Janet Kitchen who has left us with an admirable legacy Wine Tasting and who was dragged back to the coal face even after a Kew National Archives well-earned retirement. We must all wish her well in a far- flung part of the country where she is just out of reach but Musical Theatre: Legally Blonde happy in a new life. Talk at Royal Geographical Soc I have some challenges ahead of me and one of these is to increase the numbers attending our events and what LPO at RFH better way can we achieve this than by presenting to you our upcoming program. This ranges from guided walks to Talk: UCL Brain Sciences a classical concert, opera, a choral recital at Westminster Abbey and a private tour of Fitzrovia Chapel. One of Purcell Choir: Westminster Abbey our ever popular walks is to be led by our very popular UC Opera: Orpheus & Eurydice Stephen Senior, himself an alumnus as a post-graduate of the Bartlett School and so a real expert in architectural Fitzrovia Chapel private tour history. -

Community Engagement for Health Via Coalitions, Collaborations and Partnerships (On-Line Social Media and Social Networks)

EPPI-Centre Review 3: Community engagement for health via coalitions, collaborations and partnerships (on-line social media and social networks) A systematic review and meta-analysis Gillian Stokes, Michelle Richardson, Ginny Brunton, Meena Khatwa, James Thomas EPPI-Centre Social Science Research Unit UCL Institute of Education University College London EPPI-Centre report • July 2015 REPORT The authors of this report are: G Stokes, M Richardson, G Brunton, M Khatwa, J Thomas (EPPI-Centre). Funding This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The views expressed are not necessarily those of NICE. Conflicts of interest There were no conflicts of interest in the writing of this report. Contributions The opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the EPPI-Centre or the funders. Responsibility for the views expressed remains solely with the authors. This report should be cited as: Stokes G, Richardson M, Brunton G, Khatwa M, Thomas J (2015) Review 3: Community engagement for health via coalitions, collaborations and partnerships (on-line social media and social networks) – a systematic review and meta- analysis. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London. ISBN: 978-1-907345-79-1 © Copyright 2015 Authors of the systematic reviews on the EPPI-Centre website (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/) hold the copyright for the text of their reviews. The EPPI-Centre owns the copyright for all material on the website it has developed, including the contents of the databases, manuals, and keywording and data-extraction systems. The centre and authors give permission for users of the site to display and print the contents of the site for their own non-commercial use, providing that the materials are not modified, copyright and other proprietary notices contained in the materials are retained, and the source of the material is cited clearly following the citation details provided. -

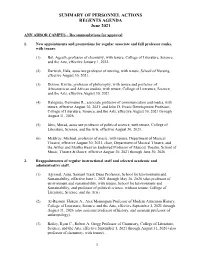

ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for Approval

SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA June 2021 ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 1. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, with tenure. (1) Bol, Ageeth, professor of chemistry, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective January 1, 2022. (2) Darwish, Hala, associate professor of nursing, with tenure, School of Nursing, effective August 30, 2021. (3) Dotson, Kristie, professor of philosophy, with tenure and professor of Afroamerican and African studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 30, 2021. (4) Halegoua, Germaine R., associate professor of communication and media, with tenure, effective August 30, 2021, and John D. Evans Development Professor, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 30, 2021 through August 31, 2026. (5) Idris, Murad, associate professor of political science, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 30, 2021. (6) McElroy, Michael, professor of music, with tenure, Department of Musical Theatre, effective August 30, 2021, chair, Department of Musical Theatre, and the Arthur and Martha Hearron Endowed Professor of Musical Theatre, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 30, 2021 through June 30, 2026. 2. Reappointments of regular instructional staff and selected academic and administrative staff. (1) Agrawal, Arun, Samuel Trask Dana Professor, School for Environment and Sustainability, effective June 1, 2021 through May 30, 2026 (also professor of environment and sustainability, with tenure, School for Environment and Sustainability, and professor of political science, without tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts). (2) Al-Rustom, Hakem A., Alex Manoogian Professor of Modern Armenian History, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective September 1, 2021 through August 31, 2026 (also assistant professor of history, and assistant professor of anthropology). -

Spohr Bicentenary in Britain

Although 1984 is far from over yet, most of the Spohr events in Britain that can be attributed to the Bicentenary have already happened, so it is possible to make some assessment of the achievements so far. There has of course been the broadcasting of a number of little-known works for which we must be very grateful to Anthony Friese-Greene of BBC Radio ;. As far as live performances are concerned London has seen most of the action. By far the most significant Spohr event this year has been the production of the opera 'Faust' by University College Opera at the Bloomsbury Theatre in February. Inspite of the lukewarm attitude of the newspaper critics this production must have persuaded most of those who actually attended that Spohr is a composer worth taking seriously. Another major work to receive its first full-scale performance in London for a long time was the oratorio 'The Last Judgement', put on by the Chelsea Harmonic Society on April 4th. It is a pity that there have not been more performances of it this year - it could have sounded splendid in one of the Proms in the Albert Hall. Another fine work that had not been heard in a concert for many years is the Double Quartet no.4 in G minor, which was given by the Academy of St.Martin-in-the- Fields Chamber Ensemble on April 29th. The Radio; broadcast on September 2nd will give those who have missed it so far a further chance to hear this beautiful and subtle work and it will be available on record soon. -

In the Market for Love Or Onions Are Forever

Autumn Performances 2020 In the Market for Love or Onions are Forever PERFORMANCES ON 10, 11, 13, 17, 18, 20, 24 AND 25 OCTOBER Welcome (back) to Glyndebourne! From March 2020’s lockdown, and Music and theatre function as a meeting the sad cancellation of the Festival point where together we can reflect, we battled to find a way back to live celebrate, grieve, question, imagine – performance. By the end of the summer and laugh! The roots of comic opera, It’s been an we managed to present a programme opera buffa, reach back to the commedia of open gardens, garden concerts dell’arte: the improvised Italian form extremely and outdoor opera as our positive which sprang up in the hurly-burly of challenging last response to the restrictions of Covid-19: the marketplace. Satirical, ribald and an attempt to find a responsible, ridiculous, playing with social status and few months for appropriately distanced, and above sexual desire, this approach to theatre everybody. all, safe way of performing to a live found a natural home in opera from audience. Next, we set our sights on Pergolesi’s La serva padrona onwards. A our autumn performances – clearly they century later and Offenbach, the master could not go ahead as planned, but we of adapting to changing circumstances, refused to be beaten. So, it is with the wrote countless bouffes. Farcical, cheeky greatest pleasure that we have arrived at and downright risqué, his energetic, this moment, finally together again, this supremely skilful musical and theatrical time indoors, to experience high calibre craft was so popular that it forced a music making. -

Casts for the Verdi Premieres in London, 1845-1977 (Part 2) Martin Chusid New York University

Verdi Forum Number 6 Article 6 3-1-1979 Casts for the Verdi Premieres in London, 1845-1977 (Part 2) Martin Chusid New York University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/vf Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chusid, Martin (1979) "Casts for the Verdi Premieres in London, 1845-1977 (Part 2)," Verdi Forum: No. 6, Article 7. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Verdi Forum by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Casts for the Verdi Premieres in London, 1845-1977 (Part 2) Keywords Giuseppe Verdi, opera, London This article is available in Verdi Forum: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/vf/vol1/iss6/6 Casts for the Verdi Premieres in London (1845-1977), Part 2 by Martin Chusid 15. June 22, 1876 Aida (Cairo, 1871). Covent Garden' Adelina Patti (Aida) Ernestina Gindele (Amneris) Ernesto Nicolini 2 (Radames) Francesco Graziani 3 (Amonsaro) Feitlinger (King) Capponi• (Ramphis) Bianca Bianchi (High Priestess) Enrico Bevignani, cond. 1 cast from review in the Illustrated London News of July I, 1876, and from Figaro as reported in Dwight's Journal of July 22, 1876 2 second husband of Adelina Patti; sang Fenton at US premiere ofFa/staff, February 4, 1895 3 see also Trovatore and Don Carlo I • probably Giovanni Capponi who sang Philip in the Italian premiere of Don Carlos (Bologna, 1867) 16. June 19, 1880 La forza del destino (revised version, Milan, 1869). -

Rush Hour Recital Friday 18 May 2018, 5.30Pm St Pancras Parish Church

The London Festival of Contemporary Church Music Rush Hour Recital Friday 18 May 2018, 5.30pm St Pancras Parish Church “Setting the Seal” University College London Chamber Choir Charles Peebles pre-concert talk at 5pm by John Woolrich and Howard Skempton Programme John Woolrich Spring in Winter 1954 – Howard Skempton Three Motets 1947 – i. Locus iste ii. Beati quorum via integra est iii. Ave Virgo sanctissima John Woolrich Earth grown old Howard Skempton Rise up, my love i. Rise up, my love ii. How fair is thy love iii. My beloved is gone down iv. How fair and how pleasant John Woolrich Paradise William Walton Set me as a seal upon thine heart 1902 – 1983 Notes In anticipation of the marriage of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle the day after this concert, William Walton’s anthem written for a 1938 society wedding sets the seal on this programme of choral music by two very different contemporary British composers: Howard Skempton and John Woolrich. The music of distinguished British composer John Woolrich has been performed all over the world. He has written in all forms, including a great variety of orchestral music, as well as for voices. He was Artistic Director of both the Dartington and the Aldeburgh festivals. Although the three pieces in today’s programme stem from different circumstances, they can be performed as a set. Spring in winter was a commission from King’s College, Cambridge for their advent carol service in 2001; Earth grown old a commission from Winchester College in 2003; and Paradise a commission from the Benchers of Gray’s Inn in 2000, to mark the turn of the millennium.