City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Queen Guinevere

Ingvarsdóttir 1 Hugvísindasvið Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskudeild Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir Kt.: 060389-3309 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 3 Abstract This essay is an attempt to recollect and analyze the character of Queen Guinevere in Arthurian literature and movies through time. The sources involved here are Welsh and other Celtic tradition, Latin texts, French romances and other works from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Malory’s and Tennyson’s representation of the Queen, and finally Guinevere in the twentieth century in Bradley’s and Miles’s novels as well as in movies. The main sources in the first three chapters are of European origins; however, there is a focus on French and British works. There is a lack of study of German sources, which could bring different insights into the character of Guinevere. The purpose of this essay is to analyze the evolution of Queen Guinevere and to point out that through the works of Malory and Tennyson, she has been misrepresented and there is more to her than her adulterous relation with Lancelot. This essay is exclusively focused on Queen Guinevere and her analysis involves other characters like Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin, Enide, and more. First the Queen is only represented as Arthur’s unfaithful wife, and her abduction is narrated. We have here the basis of her character. Chrétien de Troyes develops this basic character into a woman of important values about love and chivalry. -

SEASON 2020/2021 Stickers for Programme Choice ARTISTS LIST

SEASON 2020/2021 Stickers for Programme Choice ARTISTS LIST STRING QUARTET Arditti Quartet Cuarteto Casals Quatuor Modigliani Artemis Quartett Jerusalem Quartet Quatuor Van Kuijk Belcea Quartet Novus String Quartet Schumann Quartett Brooklyn Rider Quatuor Ébène VIOLIN VIOLA CELLO Marc Bouchkov Amihai Grosz Miklós Perényi Isabelle Faust Jean-Guihen Queyras Vadim Gluzman Alisa Weilerstein Gidon Kremer Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider PIANO FORTEPIANO MANDOLIN Piotr Anderszewski Alexander Melnikov Avi Avital Saleem Ashkar Elena Bashkirova Jonathan Biss Alexander Melnikov CLARINET VOICE RECITATION Sharon Kam Georg Nigl (Baritone) Martina Gedeck CONDUCTOR ENSEMBLE PROJECTS Ariane Matiakh Brandt Brauer Frick Building Bridges Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider Ensemble Beethoven Cycle Scharoun Ensemble International ARDITTI QUARTET & JAKE ARDITTI STRING STRING QUARTET & COUNTER-TENOR Dillon: String Quartet No. 9 Paredes: “Canciones Lunáticas” QUARTET Henze: String Quartet No. 5 Sciarrino: “Cosa resta” On the occasion of the string quartet biennals in Paris and Amsterdam, as well as at the invitation of the Cologne Philharmonie, several world premieres are pending, by Ben Mason and Christian Mason, as well as Betsy Jolas and Toshio Hosokawa. ARTEMIS QUARTETT The Artemis Quartett, in their new top-class lineup, has created a first programme for the fall of 2020. Additional ones for the spring of 2021 to follow. Mendelssohn: String Quartet No. 2 in A minor, Op. 13 Vasks: New work for String Quartet (2020) Beethoven: String Quartet No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132 BELCEA QUARTET In the fall of 2020 with the Beethoven string quartet cycle, however, already fully booked. Spring 2021: Britten: String Quartet No. 1 in D major, Op. 25 Shostakovich: String Quartet No. -

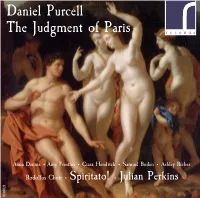

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

Commissioned Orchestral Version of Jonathan Dove’S Mansfield Park, Commemorating the 200Th Anniversary of the Death of Jane Austen

The Grange Festival announces the world premiere of a specially- commissioned orchestral version of Jonathan Dove’s Mansfield Park, commemorating the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen Saturday 16 and Sunday 17 September 2017 The Grange Festival’s Artistic Director Michael Chance is delighted to announce the world premiere staging of a new orchestral version of Mansfield Park, the critically-acclaimed chamber opera by composer Jonathan Dove and librettist Alasdair Middleton, in September 2017. This production of Mansfield Park puts down a firm marker for The Grange Festival’s desire to extend its work outside the festival season. The Grange Festival’s inaugural summer season, 7 June-9 July 2017, includes brand new productions of Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, Bizet’s Carmen, Britten’s Albert Herring, as well as a performance of Verdi’s Requiem and an evening devoted to the music of Rodgers & Hammerstein and Rodgers & Hart with the John Wilson Orchestra. Mansfield Park, in September, is a welcome addition to the year, and the first world premiere of specially-commissioned work to take place at The Grange. This newly-orchestrated version of Mansfield Park was commissioned from Jonathan Dove by The Grange Festival to celebrate the serendipity of two significant milestones for Hampshire occurring in 2017: the 200th anniversary of the death of Austen, and the inaugural season of The Grange Festival in the heart of the county with what promises to be a highly entertaining musical staging of one of her best-loved novels. Mansfield Park was originally written by Jonathan Dove to a libretto by Alasdair Middleton based on the novel by Jane Austen for a cast of ten singers with four hands at a single piano. -

The Inventory of the David Harsent Collection #1721

The Inventory of the David Harsent Collection #1721 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Harsent, David #1721 1/3/06 Preliminary Listing I Manuscripts. Box 1 A. Poetry collections. 1. A BIRD'S IDEA OF FLIGHT. a. Draft (alternate title "Notes From the Underground"), TS, 47 p., no date. [F. 1] b. Draft, TS with holograph notes, 79 p. c. Draft, TS, 82 p. [F. 2] d. Draft, TS with holograph notes, 84 p .. e. Revisions for various poems, approx. 2,500 p. total, TS and holograph. [F. 3-1 O] 2. CHILDREN'S POEMS, TS, approx. 30 p.; includes correspondence from DH. [F. 11] 3. DEVON REQUIEM, TS, approx. 25 p.; includes partial draft of "Mr. Punch." [F. 12] 4. THE HOOP OF THE WORLD, TS, 35 p. 5. LEGION, TS, 89 p.; includes revisions, TS and holograph, approx. 600 p. [F. 13-15] Box2 6. MARRIAGE AND LEPUS, TS, 61 p.; includes revisions, TS and holograph, approx. 500 p. [F. 1-3] 7. NEWS FROM THE FRONT, TS, 94 p.; includes revisions, TS and holograph, approx. 750 p. [F. 4-10] 8. NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND, TS, approx. 50 p. [F. 11] 9. THE POTTED PRIEST, TS, 65 p. 10. A VIOLENT COUNTRY, TS and holograph, approx. 100 p. [F. 12-13] 11. THE WINDHOUND, TS. [F. 14] 12. Miscellaneous text fragments of poems, revisions re: MARRIAGE; NEWS FROM THE FRONT; BIRD'S IDEA OF FLIGHT, TS and holograph; includes early unpublished poems. B. Novels. 1. BETWEEN THE DOG AND THE WOLF, 2 drafts, TS, 353 p. and 357 p.; includes holograph notes, synopsis, research material, plot progression. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

2017 Season 2

1 2017 SEASON 2 Eugene Onegin, 2016 Absolutely everything was perfection. You have a winning formula Audience member, 2016 1 2 SEMELE George Frideric Handel LE NOZZE DI FIGARO Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE Claude Debussy IL TURCO IN ITALIA Gioachino Rossini SILVER BIRCH Roxanna Panufnik Idomeneo, 2016 Garsington OPERA at WORMSLEY 3 2017 promises to be a groundbreaking season in the 28 year history of Cohen, making his Garsington debut, and directed by Annilese Miskimmon, Garsington Opera. Artistic Director of Norwegian National Opera, who we welcome back nine years after her Il re pastore at Garsington Manor. We will be expanding to four opera productions for the very first time and we will now have two resident orchestras as the Philharmonia Orchestra joins us for Our fourth production will be a revival from 2011 of Rossini’s popular comedy, Pelléas et Mélisande. Il turco in Italia. We are delighted to welcome back David Parry, who brings his conducting expertise to his 13th production for us, and director Martin Duncan Our own highly praised Garsington Opera Orchestra will not only perform Le who returns for his 6th season. nozze di Figaro, Il turco in Italia and Semele, but will also perform the world premiere of Roxanna Panufnik’s Silver Birch at the conclusion of the season. To cap the season off we are very proud to present a brand new work commissioned by Garsington from composer Roxanna Panufnik, to be directed Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy’s only opera and one of the seminal works by our Creative Director of Learning & Participation, Karen Gillingham, and I of the 20th century, will be conducted by Jac van Steen, who brought such will conduct. -

"Woman.Life.Song" by Judith Weir Heather Drummon Cawlfield

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-1-2015 Study and analysis of "woman.life.song" by Judith Weir Heather Drummon Cawlfield Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Cawlfield, Heather Drummon, "Study and analysis of "woman.life.song" by Judith Weir" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 14. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2015 HEATHER DRUMMOND CAWLFIELD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School STUDY AND ANALYSIS OF woman.life.song BY JUDITH WEIR A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Heather Drummond Cawlfield College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Music Performance May 2015 This Dissertation by: Heather Drummond Cawlfield Entitled: Study and Analysis of “woman.life.song” by Judith Weir has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Performing Arts in School of Music, Program of Vocal Performance Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ______________________________________________________ Melissa Malde, D.M.A., Research Advisor ______________________________________________________ Brian Luedloff, M.F.A., Co-Research Advisor (if applicable) _______________________________________________________ Robert Ehle, Ph.D., Committee Member _______________________________________________________ Susan Collins, Ph.D., Committee Member Date of Dissertation Defense _________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

PRESSQUOTES Owen Gilhooly

PRESSQUOTES Owen Gilhooly BARITONE Valentin / Faust / Everyman Theatre & Cork Operatic Society / March 2015 Cond. & Dir. John O’Brien “A wealth of duets, trios and quartets endorses the magic of the classic tradition, a genre well suited to Owen Gilhooly’s fine Valentin” (The Irish Times) Bridegroom, Husband, Father / The Vanishing Bridegroom / NMC Recordings Ltd / 2014 Cond, Martyn Brabbins / BBC Symphony Orchestra “Mr. Gilhooly is unbothered by the difficulty of his music, and his ringing, masculine tone gives the solo singing a firm, bronzed core.” (Voix des Arts) R (Robert) / Through his Teeth / Royal Opera House / 2014 Cond. Sian Edwards / Dir. Bijan Sheibani “‘R’, played with wonderfully irresistible confidence by Owen Gilhooly” (Opera / Hugo Shirley) “Owen Gilhooly plays the devious R with chilling precision – one moment kind and loving, and the next a scheming monster. His opening scene (scene two of the work) is fairly high in the voice, and Gilhooly displays a full range of dynamics, even in this part of the voice. He very effectively plays the part of a man who is playing a part – something which is never easy.” (Bachtrack / Levi White) “As R, baritone Owen Gilhooly, making his Royal Opera debut, looks the part and sounds it as well; his voice has all the requisite heft.” (Seen & Heard International / Colin Clarke) “Owen Gilhooly manages to combine sexual allure with fanaticism to chilling effect” (WhatsOnStage / Keith McDonnell) “Anna Devin as the deluded A, Owen Gilhooly as the mendacious R, and Victoria Simmonds, doubling