Robert Novell Year in Review 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TWA, Departs the World’S Gers, Not Mail, Unlike Most Other Airlines Skies in Almost the Same Industry Envi- PART I in Those Days

rans World Airlines, with one of the month; copilots, $250. most recognized U.S. airline sym- TAT was developed to carry passen- bols, TWA, departs the world’s gers, not mail, unlike most other airlines skies in almost the same industry envi- PART I in those days. TAT’s transcontinental ronment in which it came into being— As TWA ended its 71 years of air/rail service would take passengers the end of an unfettered period of ex- cross-country in 2 days instead of 3, as pansion marked by consolidation of air- continuous operations, it was rail-only travel required. On the west- lines. Born of a 1930 merger, TWA had the United States’ longest to-east schedule, passengers would most of its assets purchased by Ameri- board a Ford Trimotor at Los Angeles can Airlines on April 9, 2001, to end flying air carrier. at 8:45 a.m. (PST), deplane at Clovis, TWA’s run as the longest-flying air car- N.M., at 6:54 p.m. (MST) for a night rail By Esperison Martinez, Jr. rier in U.S. commercial aviation. Still, trip to Waynoka, Okla., via the Topeka Contributing Editor its 71 years of flying millions of passen- & Santa Fe Railroad, followed by an 8- gers throughout the world, of record- hour 8-minute Trimotor flight to Colum- ing achievements that won’t be quickly bus, Ohio, then onto the Pennsylvania duplicated, of establishing sterling stan- manager of NAT, became TAT vice- Railroad to arrive in New York City the dards of operations, safety, and profes- president. -

Dec 05I.Indd

January 2006 No.30 ISSN 1039 - 5180 From the Director NT History Grants Welcome to the fi rst Records Territory for 2006. 2005 was the year The grants scheme provides an annual series of fi nancial grants of systems as we implemented a new archives management to encourage and support the work of researchers who are system and managed the upgrade of the document and records recording and writing about Northern Territory history. management system across the Government. Details of successful History Grant recipients for 2005 and Focus on the systems will continue in 2006 as we continue to completed projects from other history grant recipients can be populate the archives management system with information found on page 3. about our archives collections and holdings, and we will be determining the future model for delivery of the document and Please contact Cathy Flint (contact details are on the back of this records management system for Government agencies. newsletter) if you have any queries relating to the grants. In this issue we report on various outcomes from the NT History We congratulate Pearl Ogden, a history grant recipient in Grants program, and we review the wanderings of some of 2004, for the completion of her research on the people of the our staff promoting oral history services and the Alice Springs Victoria River region. archives. We provide a snapshot of the range of fascinating archives collections which have been accessioned over the past few months in Darwin and Alice Springs, and I trust you will enjoy our spotlight on aviation history Flying High. -

The Reims Air Races

Reims Air races and the Gordon Bennett Trophy Bleriot's cross-Channel flight excited Europe as nothing else had. The City of Reims and the French vintners of the Champagne region decided to sponsor a week of aviation exhibition and competition, putting up large purses in prize money, the most prestigious being the International Aviation Cup, known as the Gordon Bennett Trophy, after its sponsor, James Gordon Bennett, the flamboyant American publisher of the New York Herald and the Paris Herald. The meet attracted the cream of European society, from royalty and generals to ambassadors and the merely wealthy, to the Betheny Plain outside Reims from August 22 to 29, 1909. While there were to be many other such meets before and after World War 1, none would match Reims for grandeur and elegance or for sheer excitement. The major European manufacturers, all French, entered various events. There were 'planes by Bleriot, Voisin, Antoinette, and Farman, and even several French-built Wrights. The Wrights themselves had passed on an invitation to race at Reims, which was awkward since the Gordon Bennett Trophy was crowned with a large replica of a Wright Flyer. The Aero Club of America, which had sponsored the Scientific American trophy won by Curtiss a year earlier, turned to Curtiss. Curtiss' June Bug was not as well developed a plane as the Wright machines (and possibly the Wrights were hoping to drive this point home if Curtiss failed at Reims) and while it was more maneuverable than the European planes, it was not nearly as fast. 1909 Voisin 1 Curtiss worked feverishly to produce a more powerful engine and stripped down his airplane to give it greater speed. -

“TWA– the Building of an Airline, As Revealed in the Private Collection of Co-Founder Paul Ernest Richter, Jr.” 1924 - 1949

“TWA– The Building of an Airline, as revealed in the private collection of co-founder Paul Ernest Richter, Jr.” 1924 - 1949 “The Three Musketeers of Aviation” Walt Hamilton, Jack Frye, Paul Richter ̶ 1 ̶ Overview TWA, The Airline Run by Flyers The Real story 1924 - 1949 Three young aviators with a common vision become the founders of “Trans World Airlines” A Documentary It was the 1920s, the “Golden Age of Aviation”, a time when pilots flew through barns and walked on wings. In this age of barnstorming and daring feats, three young pilots- Paul Richter, Jack Frye and Walter Hamilton took a chance with their life savings and purchased an airplane for the purpose of starting their own flight school. Within a short time, that one airplane grew to an airline fleet that pioneered the first passenger route system throughout the Southwest and forged the framework for modern air travel. Known then as the “Three Musketeers of Aviation”, these three young aviators with a common vision became better known as the founding fathers of Trans World Airlines. Trans World Airline set the standards throughout “the Golden Age of Aviation”. TWA was unique because TWA was founded by flyers. Jack Frye, Paul Richter and Walt Hamilton were visionaries of aviation; three men passionate about flying; always striving to reach for the impossible. From 1924 through 1947 their partnership and dedication to creating the best, established TWA as the leader in commercial aviation. This is the true story of the early years of TWA as told by Ruth Richter Holden, daughter of TWA founder Paul E. -

Flightplan ! ! Flightplan Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum

1 FLIGHTPLAN! A VOLUNTEER NEWSLETTER FOR VOLUNTEERS Your Newsletter Staff- Co-Editors: Ann Trombley, [email protected] Katha Lilley, [email protected] Feature writers: Bob Peterman, Spencer Vail, Bob Osborn, Bruce Anderson, Earl Scott , John Jennings, Lynn Gelinas Contributors: Don Trombley, Jim Lilley Guest Contributors: Melba Smith, Bob Ruck, Wayne Swanson FEBRUARY 2013 Volume Issue9 2 “A Volunteer Newsletter by Volunteers” by Newsletter Volunteer “A FLIGHTPLAN ! FLIGHTPLAN EVERGREEN AVIATION & SPACE MUSEUM 2 FLIGHTPLAN! A VOLUNTEER NEWSLETTER FOR VOLUNTEERS ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE. BUT A LITTLE CHOCOLATE NOW AND THEN DOESN’T HURT. CHARLES M. SCHULTZ 2- Marlene Lee FEBRUARY 3- Alexander Dondaville BIRTHDAYS 3- Jack Dowty 3- Steve Thomson 3- Roger Weeks Our Mission- 4-Wesley Lawson 16- Michael Bell 4- John Persha 18- Nick (Walter) Majure 4- Sylvia Morley 18- Marlane Wood To inspire 5- Jack Burock 19- Elinore Henderson and educate 5- George Heimos 20- Lee Danielson 6- Bruce Bothwell 20- Mary Lou Lunde To promote and 6- Dick Johnson 21- Michael Eastes preserve aviation 8- Terry Dickerson 22- Myron Cline and space history 8- Dee Hemmendinger 23- Matthew Lowry 9- Hal Augee 23- Dick Wood To honor the 9- Edward Shellenbarger 24- Dave Reitz patriotic service of 11-Erich Hintz 24-James Winters our veterans 11- Loren Otto 25- David Hatfield 11- Lois Berry 25- Ray Mader 12- Rod Church 26- Vivian Peterson 12- John Holliday 27- Wayne Swanson 12- Ed Onstott 28- Ron Toxler 13- CM Stordahl 28- Larry Smith 14- Dwayne Cole 31- Jim Hermans 14- Robert Ames Is your Birthday missing from the list??? Send an email to Katha Lilley [email protected] 3 FLIGHTPLAN! A VOLUNTEER NEWSLETTER FOR VOLUNTEERS tin’s seaplanes and had it shipped getting his hair cut in San Diego, back to his home in Seattle. -

Risking Life and Limb Fora Thrill

THE PLAIN DEALER . SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 1998 5-D OURCENTURY 1934 ATA GLANCE Risking life and limb for a thrill PD FILE A shantytown at Whiskey Island, east of E. 9th St. Politics mirror bad U.S. economy Never had there been so much political agi- tation. Louisiana Gov. Huey Long, who gloried in the nickname “the Kingfish,” proclaimed “Every man a king!” until he was assassi- nated. Gerald L.K. Smith led the isolationist America First Party. The elderly rallied behind Dr. Francis Townsend’s Townsend Plan to pay them $200 a month so they could spend the nation into prosperity. From Detroit, Father Charles Coughlin, “the radio priest,” assailed bankers and Jews until his bishop silenced him. The school superintendent of Gary, Ind., de- clared that he had been offered $1 million to lead a Communist plot to seize the govern- ment. In San Diego, a fascist group calling it- self the Silver Shirts planned to attack the Communist May Day Parade, then seize City Hall and “liquidate” a Jewish deputy sheriff. On Oct. 28, about 150 Communists stormed the doors of Cleveland City Hall during a City Council meeting in an effort to present de- mands for greater relief for the poor. Police blocked their entrance, but arranged for their leaders to meet with Mayor Harry L. Davis. Party members vowed to demonstrate at the homes of council members. WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Still, a Chamber of Commerce survey Barnstorming pilot Roscoe Turner, right, mugs for the camera with Frederick Crawford, left, after winning a showed manufacturing employment up 5.5 Thompson Trophy race. -

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Mass Communications

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE AN HISTORICAL DOCUMENTARY FIU1 SCRIPT ., \ DETAILING THE RESEARCH PROCESS 1. A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Mass Communications by James Drake -·Algar August, 1978 The thesis of James Drake Algar is approved i i I r' California State University, Notthridge August, 1978 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT •• v Introduction to the Project 1 Intdroduction to the Subject 5 Subject Research 11 Materials Research 33 Script . 58 Concl us·ion 78 NOTES 80 BIBLIOGRAPHY 86 i; i ' ' LIST OF TABLES Page The National Air Races, 1929-1939 ..... 11 New York Times Articles , National Air Races, 1930-1939 19 Pilots and Personalities, National Air Races, 1929-1939 . 44 Participating Aircraft, National Air Races, 1929-1939 45 Locations and Eve~ts, National Air Races, 1929-1939 45 Dates, National Air Races, 1929-1939 .. 45 Fox Movietone Negative File Numbers and Length. 52 iv ABSTRACT AN HISTORICAL DOCUMENTARY FILM SCRIPT DETAILING THE RESEARCH PROCESS by James Drake Algar Master of Arts in t~ass Corrmuni cations August, 1978 The documentar·y film has taken a rightf~.,;l place as a legitimate form of historical work. One long-practiced form of documentary film is that in which the primary materials used are already-existing film and photographic stills. Compiled, re-filmed and edited in accorda~ce \vith a written script and narration, such an "archival'! documentary film can be a powerful and useful addition to the existing hi stOi'.Y of any subject. This thesis details the process and steps by which historical information on a chosen subject is researched. -

Robert Novell Year in Review 2011

Robert Novell Year in Review 2011 1 Table of Contents 1. A Brief History of United Airlines 3 2. A Brief History of TWA Airlines 40 3. A Brief History of Eastern Airlines 74 4. Closing Thoughts 116 2 Part One United Airlines before the Deregulation Act of 1938 United Airlines officially began airline operations in 1926 as a mail carrier. It was also the first fare- paying airline to fly customers from coast to coast in the United States, and by 1930, had introduced the concept of an airline stewardess. The airline soon became one of the “Big Four” contenders in the U.S. and continues to be one of America’s major airlines. It was founded in Boise, Idaho. United Airlines was originally formed as a partnership between Boeing Airplane Company and Pratt & Whitney. It was overseen by the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation and United Air Lines was actually an operating division that was established on July 1, 1931. United’s slogan was the “World’s Largest Air Transport System”. The four transport divisions of the United Aircraft and Transportation Corporation had now become United Airlines. When the Air Mail Act of 1934 broke up all of the aviation holding companies in the United States, the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation was broken up into Boeing, United Aircraft and United Air Lines. It was at this time that United Airlines began offering coast-to-coast service from New York to San Francisco and Los Angeles. Within four months of the beginning coast-to-coast operations, United Air Lines was making as many as 11 round trips every day between Chicago and New York. -

ROSCOE TURNER FLIGHT STRIP an Innovation in Accessibility Opened at Shades State Park

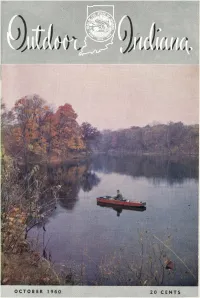

J fJ/ , /J aJ J , I IIII I I III {{ l I ' I I -0 t . _c r. OCTOBER 1960 20 CENTS OUTDOOR IN DIVISIONS AND DIR Enforcement-John D. Ia Engineering-Henry Ck Entomology-John J. F Fish and Game-Hugh G Forestry-Ralph F. Wilcox Geological Survey-John B. CONTENTS LT. GOV. PARKER TOURS CONSERVATION EXHIBITS...... 1 "HUNT AM ERICA TIM E"................................................ 2 FIRE DANGER! PROTECTION AND PREVENTION............ 3 COLLARED BUCKS ARE LEGAL GAME ............................. 4 UPLAND GAME SEASONS SET..................... .............. 5 NEWSOGRAM ....................................................... 6 ROSCOE TURNER FLIGHT STRIP DEDICATED .................. 8 WILDLIFE DISTRIBUTION SURVEY MAPS...................... 11 KNOW YOUR DUCKS-FIELD GUIDE FOR HUNTERS........ 16 "IT'S THE DANIEL BOONE INFLUENCE"................... 18 STRANGER THAN FICTION-CITY RAISED QUAIL.......... 23 CONSERVATION CORPORATION DIRECTORS MEET........ 26 REDHEAD AND CANVASBACK RESTRICTIONS........... 29 ELM ER ....................................... ................... 30 MIDWEST NURSERYMEN MEET ....................................... 31 STRATA DATA-GEOLOGY BRIEF ........................... 3rd Cover Vol. IV, No. 4 OUTDOOR INDIANA October, 1960 WALTER L. THOMPSON, Editor MARJORIE J. GROVER, Associate Editor MAC HEATON, Art Editor HERMAN MACKEY, Photo Editor PEGGY JONES, Circulation Published monthly by the Indiana Department of Conservation, 311 W. Washington St., Indianapolis 9. Subscription price $1.50 a year. Second-class mail privileges authorized -

Historical Perspective BOEING FRONTIERS

Historical Perspective BOEING FRONTIERS 75 years ago, Boeing introduced the Model 247, the world’s 1st modern airliner n 1933, the world was at the depth of the Great Depression. But standing in stark contrast to this economic crisis was the avia- Ition industry, which was experiencing a period of growth and rapid change as air travel started to become something more than a novelty. New air routes were crossing the United States, allowing coast-to-coast passenger travel as well as the delivery of freight and mail. All that was needed was speed. Advances in the science of airplane structures made it possi- ble to leave behind wood and fabric in favor of stronger all-metal 10 APRIL 2008 BOEING FRONTIERS Historical Perspective BOEING FRONTIERS It took the Model 247 20 hours, with sev- planes. At the time this huge order was a The first Boeing Model 247 is parked en stops, to fly between New York and Los tremendous boon for Boeing, but it would outside the Boeing hangar on the east Angeles. While that may seem like a long trip quickly turn out to be a miscalculation side of Boeing Field in Seattle the day by today’s standards, it was more than seven that essentially knocked Boeing out of the before it would make its first flight. hours faster than any other airliner. The abil- commercial airplane business until the in- BOEING ARCHIVES PHOTO ity to cross the United States in less than a troduction of the 707. day changed air travel overnight. At the time both the Boeing Airplane Boeing was at the forefront of modern Company and United Air Lines were airplane design and had been a pioneer subsidiaries of the United Aircraft and in the introduction of all-metal mono- Transport Corporation, and it was only nat- plane designs, leading with the Model ural for Boeing to support United in achiev- 200 Monomail and also pioneering the ing an edge over its competition. -

Extensions of Remarks 15467 Extensions of Remarks Igor I

June 11, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 15467 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS IGOR I. SIKORSKY AND IDS GREEN designers, never flew," and (when asked why SALUTE TO THE "GREEN GIANTS" GIANTS: TRIDUTES TO THE MAN his first helicopter did not fly), "Insufficient (By Mrs. Helen Glasgow, Bridgeport, Conn., AND IDS MACHINES knowledge, insufficient horsepower." dedicated to the Sikorsky HH-3E helicop Among those seated at the head table with ters on their first transatlantic flight, May Mr. Sikorsky were Mrs. Sikorsky, Capt. Ed 31, 1967) HON. ROBERT N. GIAIMO ward V. Rickenbacker, Brig. Gen. H. Franklin We salute you, Green Giants Gregory, USAF (ret.), pioneer military heli OF CONNECTICUT On your great achievement: copter pilot; Comdr. Frank Erickson, USCG You've made it, you've made it, IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES (ret.), pioneer helicopter pilot and pilot of You made it again! Wednesday, June 11, 1969 the first helicopter mercy mission; Admiral Arthur W. Radford, USN (ret.), former head With perpetual motion Mr. GIAIMO. Mr. Speaker, one of the of the joint chiefs of staff and a helicopter You flew over the Ocean greatest pioneers of the age of fiight, Igor pilot late in his career; Arthur Godfrey, for To bring to mankind I. Sikorsky, recently celebrated his 80th mer helicopter pilot; Capt. Boris Sergievsky, God's perpetual love. birthday. I rise to pay tribute to the man test pilot of Sikorsky's flying boats; C. L. The fires are burning, the waters are churn- and his work. (Les) Morris, pioneer helicopter test pilot; ing, Clarence Chamberlin and Bernt Balchen, pio All hope for salvation is gone. -

Aircraft Engineer

{Motor Si, mt. AIRCRAFT ENGINEER AND AIRSHIPS bounded in 1909 by Stanley Spoonef FIR DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS, PRACTICE AND PROGRESS OF AVIATION OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE ROYAL AERO CLUB No. 1348. Vol. XXVI. 26th Year Thursdays. Price 6d. OCTOBER 25, 1934 By Post, 7Jd. Editorial, Advertising and Publishing Offices: DORSET HOUSE, STAMFORD STREET, LONDON, S.E.I. Telegrams: Truditur Watloo, London. Telephone: Hop 3333 (50 lines). HERTFORD ST. COVENTRY GUILDHALL BUILDINGS, . 60, DEANSGATE, MANCHESTER 3. 26B, RENFIELD ST. NAVIGATION' ST., BIRMINGHAM, :. GLASGOW C.2. elegrams: Autocar, Coventry. Telegrams: Autopress, Birmingham. Telegrams: lliffe Manchester. Telegrams: Iliffe, Glasgow, lelcphone: Coventry 5210. Telephone: Midland 2971. Telephone: Blackfriars 4412. Telephone: Ceatral 48t>7 SUBSCRIPTION Home and Canada: Year, £1 13 0: C months, 16s. 6d.- 3 months 8s. 3d. RATES: Other Countries: Year, £1 15 0, 0 mouths, 17s. ad.; 3 inouths, 8s. tfd. Three types, it may be said, were entered with definite victory II objects and policies—the "Comets," the "Douglas," and the "Boeing"—and each of them has made good E have won. Bravo Scott! Bravo Campbell and practically proved what their entrants set out to Black ! Bravo De Jiavillands ! Bravo Ratier! prove. The "Comet " was designed specifically to ful- W Bravo all others who helped in the magnifi- fil the conditions of the race, and it has fulfilled them cent achievement! completely. The other two set out to prove that the This has been the greatest long race in the whole his- new types of fast commercial aeroplanes which have tory of flying. It means so much that for the moment been developed in America (both the "Douglas" and the brain almost reels in thinking out all that it does the "Boeing" are American designs), Holland, and mean.