The Department of Justice Versus Apple Inc. -- the Great Encryption Debate Between Privacy and National Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encryption: Selected Legal Issues

Encryption: Selected Legal Issues Richard M. Thompson II Legislative Attorney Chris Jaikaran Analyst in Cybersecurity Policy March 3, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44407 Encryption: Selected Legal Issues Summary In 2014, three of the biggest technology companies in the United States—Apple, Google, and Facebook—began encrypting their devices and communication platforms by default. These security practices renewed fears among government officials that technology is thwarting law enforcement access to vital data, a phenomenon the government refers to as “going dark.” The government, speaking largely through Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) Director James Comey, has suggested that it does not want to ban encryption technology, but instead wants Silicon Valley companies to provide a technological way to obtain the content stored on a device for which it has legal authority to access. However, many in the technology community, including technology giants Apple, Google, and Facebook, and leading cryptologists have argued that it is not technologically feasible to permit the government access while continuing to secure user data from cyber threats. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that some suspects may refuse to unlock their device for law enforcement. The current debate over encryption raises a wide range of important political, economic, and legal questions. This report, however, explores two discrete and narrow legal questions that arise from the various ways the government has attempted to access data stored on a smartphone. One method has been to attempt to compel a user to either provide his password or decrypt the data contained in a device pursuant to valid legal process. -

Apple & Deloitte Team up to Accelerate Business

NEWS RELEASE Apple & Deloitte Team Up to Accelerate Business Transformation on iPhone & iPad 9/28/2016 Deloitte Introduces New Apple Practice to Help Businesses Design & Implement iPhone & iPad Solutions CUPERTINO, Calif. & NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Apple® and Deloitte today announced a partnership to help companies quickly and easily transform the way they work by maximizing the power, ease-of-use and security the iOS platform brings to the workplace through iPhone® and iPad®. As part of the joint effort, Deloitte is creating a first-of-its-kind Apple practice with over 5,000 strategic advisors who are solely focused on helping businesses change the way they work across their entire enterprise, from customer-facing functions such as retail, field services and recruiting, to R&D, inventory management and back-office systems. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160928006317/en/ Apple CEO Tim Cook and Deloitte Global CEO Punit Renjen meet at Apple's campus to Apple and Deloitte will also announce a joint effort to accelerate business transformation using iOS, iPhone & iPad. collaborate on the development (Courtesy of Apple/Roy Zipstein) of a new service offering from Deloitte Consulting called EnterpriseNext, designed to help clients fully take advantage of the iOS ecosystem of hardware, software and services in the workplace. The new offering will help customers discover the highest impact possibilities within their industries and quickly develop custom solutions through rapid prototyping. 1 “We know that iOS is the best mobile platform for business because we’ve experienced the benefit ourselves with over 100,000 iOS devices in use by Deloitte’s workforce, running 75 custom apps,” said Punit Renjen, CEO of Deloitte Global. -

Protecting Sensitive and Personal Information from Ransomware-Caused Data Breaches

Protecting Sensitive and Personal Information from Ransomware-Caused Data Breaches OVERVIEW Over the past several years, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Ransomware is a serious and increasing threat to all government and Agency (CISA) and our partners have responded to a significant number of private sector organizations, including ransomware incidents, including recent attacks against a U.S. pipeline critical infrastructure organizations. In company and a U.S. software company, which affected managed service response, the U.S. government providers (MSPs) and their downstream customers. launched StopRansomware.gov, a centralized, whole-of-government Ransomware is malware designed to encrypt files on a device, rendering webpage providing ransomware files and the systems that rely on them unusable. Traditionally, malicious resources, guidance, and alerts. actors demand ransom in exchange for decryption. Over time, malicious actors have adjusted their ransomware tactics to be more destructive and impactful. Malicious actors increasingly exfiltrate data and then threaten to sell or leak it—including sensitive or personal information—if the ransom is not paid. These data breaches can cause financial loss to the victim organization and erode customer trust. All organizations are at risk of falling victim to a ransomware incident and are responsible for protecting sensitive and personal data stored on their systems. This fact sheet provides information for all government and private sector organizations, including critical infrastructure organizations, on preventing and responding to ransomware-caused data breaches. CISA encourages organizations to adopt a heightened state of awareness and implement the recommendations below. PREVENTING RANSOMWARE ATTACKS 1. Maintain offline, encrypted backups of data and regularly test your backups. -

About the Sony Hack

All About the Sony Hack Sony Pictures Entertainment was hacked in late November by a group called the Guardians of Peace. The hackers stole a significant amount of data off of Sony’s servers, including employee conversations through email and other documents, executive salaries, and copies of unreleased January/February 2015 Sony movies. Sony’s network was down for a few days as administrators worked to assess the damage. According to the FBI, the hackers are believed have ties with the North Korean government, which has denied any involvement with the hack and has even offered to help the United States discover the identities of the hackers. Various analysts and security experts have stated that it is unlikely All About the Sony Hack that the North Korean government is involved, claiming that the government likely doesn’t have the Learn how Sony was attacked and infrastructure to succeed in a hack of this magnitude. what the potential ramifications are. The hackers quickly turned their focus to an upcoming Sony film, “The Interview,” a comedy about Securing Your Files in Cloud two Americans who assassinate North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. The hackers contacted Storage reporters on Dec. 16, threatening to commit acts of terrorism towards people going to see the Storing files in the cloud is easy movie, which was scheduled to be released on Dec. 25. Despite the lack of credible evidence that and convenient—but definitely not attacks would take place, Sony decided to postpone the movie’s release. On Dec. 19, President risk-free. Obama went on record calling the movie’s cancelation a mistake. -

Who Will Be Responsible for Helping Protect National Security?

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2017 CIA or CEO: Who Will be Responsible for Helping Protect National Security? Jamie Elizabeth Crandal Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the International Business Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Crandal, Jamie Elizabeth, "CIA or CEO: Who Will be Responsible for Helping Protect National Security?" (2017). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 6829. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6829 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIA OR CEO: WHO WILL BE RESPONSILBLE FOR HELPING PROTECT NATIONAL SECURITY? by Jamie Elizabeth Crandal Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of HONORS IN UNIVERSITY STUDIES WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS in International Business in the Department of Management Approved: Thesis/Project Advisor Committee Member Dr. Shannon Peterson Profe ssor John Ferguson Honors Program Director Departmental Honors Advisor Dr. Kristine Miller Dr. Shannon Peterson UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT Spring 2017 © 2017 Jamie Crandal All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT As technology advances businesses are being called upon to take an active role in helping protect national security. A variety of different companies and industries within the private sector, which are at the forefront of encryption and hacking technologies, have the option to aid or subvert the intelligence community by sharing breakthrough technology in the interest of helping ensure domestic tranquility. -

The 2014 Sony Hack and the Role of International Law

The 2014 Sony Hack and the Role of International Law Clare Sullivan* INTRODUCTION 2014 has been dubbed “the year of the hack” because of the number of hacks reported by the U.S. federal government and major U.S. corporations in busi- nesses ranging from retail to banking and communications. According to one report there were 1,541 incidents resulting in the breach of 1,023,108,267 records, a 78 percent increase in the number of personal data records compro- mised compared to 2013.1 However, the 2014 hack of Sony Pictures Entertain- ment Inc. (Sony) was unique in nature and in the way it was orchestrated and its effects. Based in Culver City, California, Sony is the movie making and entertain- ment unit of Sony Corporation of America,2 the U.S. arm of Japanese electron- ics company Sony Corporation.3 The hack, discovered in November 2014, did not follow the usual pattern of hackers attempting illicit activities against a business. It did not specifically target credit card and banking information, nor did the hackers appear to have the usual motive of personal financial gain. The nature of the wrong and the harm inflicted was more wide ranging and their motivation was apparently ideological. Identifying the source and nature of the wrong and harm is crucial for the allocation of legal consequences. Analysis of the wrong and the harm show that the 2014 Sony hack4 was more than a breach of privacy and a criminal act. If, as the United States maintains, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (herein- after North Korea) was behind the Sony hack, the incident is governed by international law. -

Iphone 7 Plus Ipsw File Download How to Restore IPSW With/Without Itunes

iphone 7 plus ipsw file download How to Restore IPSW with/without iTunes. In our digital life, there are a lot of situations that we will need to install IPSW file on iPhone, iPad or iPod touch, like, update iOS system, restore unsigned ipsw without iTunes, downgrade iOS, repair iOS issues, restore device to factory reset and so forth. At the very beginning, we'd better figure out what the IPSW is. What is IPSW? IPSW file is the raw iOS software for iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch, which is normally used in iTunes to install iOS firmware. And iTunes utilizes the IPSW file format to store iOS firmware to restore any device to its original state. In the following, we will show you how to install iOS manually with IPSW. How to Use IPSW File to Restore/Update iPhone with iTunes. Now follow the guide below to learn how to restore iPhone with IPSW: Step 1: Download the IPSW file you want from here. Step 2: Open iTunes. Select your device by clicking the "device" icon. In the Summary panel hold the Option key and click Update or Restore if using a Mac, or hold the Shift key and click Update or Restore if using a Windwos PC. Step 3: Now select your IPSW file. Browse for the download location, select the file, and click Choose. Your device will update as if the file had been downloaded through iTunes. 1. Unsigned IPSW files are not supported. No tools in the market supports to restore unsigned IPSW files. 2. Before updating or restoring iOS with IPSW, we highly recommend you backup your files beforehand because the data will be wiped out after restoring from IPSW files. -

Attack on Sony 2014 Sammy Lui

Attack on Sony 2014 Sammy Lui 1 Index • Overview • Timeline • Tools • Wiper Malware • Implications • Need for physical security • Employees – Accomplices? • Dangers of Cyberterrorism • Danger to Other Companies • Damage and Repercussions • Dangers of Malware • Defense • Reparations • Aftermath • Similar Attacks • Sony Attack 2011 • Target Attack • NotPetya • Sources 2 Overview • Attack lead by the Guardians of Peace hacker group • Stole huge amounts of data from Sony’s network and leaked it online on Wikileaks • Data leaks spanned over a few weeks • Threatening Sony to not release The Interview with a terrorist attack 3 Timeline • 11/24/14 - Employees find Terabytes of data stolen from computers and threat messages • 11/26/14 - Hackers post 5 Sony movies to file sharing networks • 12/1/14 - Hackers leak emails and password protected files • 12/3/14 – Hackers leak files with plaintext credentials and internal and external account credentials • 12/5/14 – Hackers release invitation along with financial data from Sony 4 Timeline • 12/07/14 – Hackers threaten several employees to sign statement disassociating themselves with Sony • 12/08/14 - Hackers threaten Sony to not release The Interview • 12/16/14 – Hackers leaks personal emails from employees. Last day of data leaks. • 12/25/14 - Sony releases The Interview to select movie theaters and online • 12/26/14 –No further messages from the hackers 5 Tools • Targeted attack • Inside attack • Wikileaks to leak data • The hackers used a Wiper malware to infiltrate and steal data from Sony employee -

Ipad Benutzerhandbuch Für Ios 4.3 Software Inhalt

iPad Benutzerhandbuch Für iOS 4.3 Software Inhalt 9 Kapitel 1: Auf einen Blick 10 Tasten 12 Fach für Mikro-SIM-Karte 12 Home-Bildschirm 17 Multi-Touch-Bildschirm 19 Bildschirmtastatur 25 Kapitel 2: Einführung 25 Voraussetzungen 25 Konfigurieren des iPad 26 Synchronisieren mit iTunes 32 Herstellen der Internetverbindung 34 Hinzufügen von E-Mail-, Kontakt- und Kalender-Accounts 36 Trennen des iPad von Ihrem Computer 36 Anzeigen des Benutzerhandbuchs auf dem iPad 37 Batterie 38 Verwenden und Reinigen des iPad 40 Kapitel 3: Grundlagen 40 Verwenden von Apps 45 Drucken 48 Suchen 49 Verwenden von Bluetooth-Geräten 50 Dateifreigabe 51 Verwenden von AirPlay 52 Sicherheits- und Schutzfunktionen 54 Kapitel 4: Safari 54 Informationen über Safari 54 Anzeigen von Webseiten 58 Suchen im Internet 59 Lesezeichen 60 Weblinks 2 61 Kapitel 5: Mail 61 Informationen über Mail 61 Konfigurieren von E-Mail-Accounts 62 Senden von E-Mails 63 Abrufen und Lesen von E-Mails 66 Durchsuchen von E-Mails 67 Drucken von Nachrichten und Anhängen 68 Verwalten von E-Mails 69 Kapitel 6: Kamera 69 Informationen über Kamera 69 Aufnehmen von Fotos und Videos 71 Ansehen und Senden von Fotos und Videos 71 Trimmen von Videos 72 Laden von Fotos und Videos auf Ihren Computer 73 Kapitel 7: FaceTime 73 Informationen über FaceTime 74 Anmelden 75 Anrufen mit FaceTime 75 Während des Telefonats 77 Kapitel 8: Photo Booth 77 Informationen über Photo Booth 77 Auswählen eines Effekts 78 Aufnehmen eines Fotos 79 Anzeigen und Freigeben von Fotos 79 Laden von Fotos auf Ihren Computer 80 Kapitel -

CHAPTER 1 ORGANISATION PROFILE 1.1: History Founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak Created Apple Computer on April 1 1976,And

CHAPTER 1 ORGANISATION PROFILE 1.1: History Founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak created Apple Computer on April 1 1976,and incorporated the company on January 3, 1977, in Cupertino, California.For more than three decades, Apple Computer was predominantly a manufacturer of personal computers, including the Apple II, Macintosh, and Power Mac lines, but it faced rocky sales and low market share during the 1990s. Jobs, who had been ousted from the company in 1985, returned to Apple in 1996 after his company NeXT was bought by Apple. The following year he became the company's interim CEO, which later became permanent Jobs subsequently instilled a new corporate philosophy of recognizable products and simple design, starting with the original iMac in 1998.With the introduction of the successful iPod music player in 2001 and iTunes Music Store in 2003, Apple established itself as a leader in the consumer electronics and media sales industries, leading it to drop "Computer" from the company's name in 2007. The company is now also known for its iOS range of smart phone, media player, and tablet computer products that began with the iPhone, followed by the iPod Touch and then iPad. 1.2: Geographical region and country Apple inc was established in Cupertino, California,United States of America. Apple Inc largest geographic markets are United States of America, Europe, China, Japan, and Asia Pasific(NASDAQ;APPL). Figure 1: The percentage of Apple Inc Total Net Sales by NASDAQ for the year 2014 1.3: Type of organization 1 Apple Inc., formerly Apple Computer, Inc., is a multinational corporation that creates consumer electronics, personal computers, servers, and computer software, and is a digital distributor of media content. -

From Struggles to Stardom

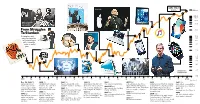

AAPL 175.01 Steve Jobs 12/21/17 $200.0 100.0 80.0 17 60.0 Apple co-founders 14 Steve Wozniak 40.0 and Steve Jobs 16 From Struggles 10 20.0 9 To Stardom Jobs returns Following its volatile 11 10.0 8.0 early years, Apple has 12 enjoyed a prolonged 6.0 period of earnings 15 and stock market 5 4.0 gains. 2 7 2.0 1.0 1 0.8 4 13 1 6 0.6 8 0.4 0.2 3 Chart shown in logarithmic scale Tim Cook 0.1 1980 ’82 ’84 ’86’88 ’90 ’92 ’94 ’96 ’98 ’00 ’02 ’04 ’06’08 ’10 ’12 ’14 ’16 2018 Source: FactSet Dec. 12, 1980 (1) 1984 (3) 1993 (5) 1998 (8) 2003 2007 (12) 2011 2015 (16) Apple, best known The Macintosh computer Newton, a personal digital Apple debuts the iMac, an The iTunes store launches. Jobs announces the iPhone. Apple becomes the most valuable Apple Music, a subscription for the Apple II home launches, two days after assistant, launches, and flops. all-in-one desktop computer 2004-’05 (10) Apple releases the Apple TV publicly traded company, passing streaming service, launches. and iPod Touch, and changes its computer, goes public. Apple’s iconic 1984 1995 (6) with a colorful, translucent Apple unveils the iPod Mini, Exxon Mobil. Apple introduces 2017 (17 ) name from Apple Computer. Shares rise more than Super Bowl commercial. Microsoft introduces Windows body designed by Jony Ive. Shuffle, and Nano. the iPhone 4S with Siri. Tim Cook Introduction of the iPhone X. -

Résumé Akshay Bakshi

� Vancouver, BC, � � 778-223-6613 Akshay Bakshi ✉ [email protected] � Profile Product manager with an engineering background and a passion for craftsmanship, experienced in shipping mobile & Mac apps at scale. � Experience Microsoft, Office for Mac and Mobile Program Manager 2 Remote in Vancouver, BC 2018 – Present - Launched Office app on iOS and revamping Word, Excel and PowerPoint for uniquely mobile scenarios. Defining product vision and managing across PM, design, data science, engineering and marketing partners located in India, China and USA. - Partnering with Apple for iPad enterprise growth (MAD up 40% YoY). - Driving core UX for Office on iOS & macOS. Working on Start, push notifications, @mentions and comments to increase collaboration (usage up 3x). - Coaching early-in-career PMs. Allyship lead for Vancouver. Program Manager Redmond, WA 2016 – 2018 - Incubated an AR+VR Office product, managing user research, design and development (NPS 70). Direct approval by Satya Nadella for productization. Received patent. - Office Accessibility lead for iOS & macOS. Lead partnership with Apple to improve VoiceOver usability. Achieved App Store feature and unblocked $10M+ business deals. - Drove the iOS 11 update for Office and marketing partnership with Apple. Program Manager Intern Redmond, WA Summer 2015 Added support for right-to-left language UI in Word, Excel & PowerPoint for iOS. Symantec, Norton for Mac Software Developer Intern Los Angeles, CA Jan – Sep 2014 Refactored remote management components and built GUI tools. � Education UCLA, B.S. in Computer Science 2012 – 2015 - President, Association for Computing Machinery. Ran committee of 12. Increased funding 4x, membership 20→200 and event attendance 6x. - Creative Director, LA Hacks - Product Manager, Daily Bruin & Bruinwalk � Skills & Life Photoshop, Obj-C, C++, Sketch.