Follow the Leaders: a Constructive Examination of Existing Regulatory Tools That Could Be Applied to Internet Gambling Ronnie D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Ministry Church Ministry Manuals

Empowering and encouraging leaders to do church ministry effectively! Music Ministry Church Ministry Manuals Dr. Byan Cutshall SERIES 44335 Music Ministries Manual.qxp 1/5/07 4:26 PM Page 4 44335 Music Ministries Manual.qxp 1/5/07 4:26 PM Page 4 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are taken from the New King James Version. Copyright © Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are taken from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1979, 1980, 1982, 1990, 1995, Thomas Nelson Inc., Publishers. 1979, 1980, 1982, 1990, 1995, Thomas Nelson Inc., Publishers. Book Editor: Wanda Griffith Book Editor: Wanda Griffith Editorial Assistant: Tammy Hatfield Editorial Assistant: Tammy Hatfield Copy Editors: Esther Metaxas Copy Editors: Esther Metaxas Jessica Sirbaugh Jessica Sirbaugh ISBN: 978-1-59684-220-5 ISBN: 978-1-59684-220-5 Copyright © 2006 by Pathway Press Copyright © 2006 by Pathway Press Cleveland, Tennessee 37311 Cleveland, Tennessee 37311 All Rights Reserved All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Printed in the United States of America 44335 Music Ministries Manual.qxp 11/15/06 10:47 AM Page 5 44335 Music Ministries Manual.qxp 11/15/06 10:47 AM Page 5 ContentsThe Table of ContentsThe Table of Acknowledgments . 7 Acknowledgments . 7 Chapter One Chapter One The Minister and the Music . 9 The Minister and the Music . 9 Chapter Two Chapter Two Training the Team . 13 Training the Team . 13 Chapter Three Chapter Three Organizing the Music Ministry . 19 Organizing the Music Ministry . 19 Chapter Four Chapter Four Working in a Church . 27 Working in a Church . 27 Chapter Five Chapter Five Touring, Recording and Copyright Laws . -

Follow the Leaders in Newbery Tales

Carol Lautenbach Follow the Leaders in Newbery Tales oday’s youth are tomorrow’s leaders.” weren’t waiting for adulthood before putting their This statement, or some variation of it, skills to productive use. “T can be seen on billboards, promotional I selected eight leadership perspectives for this brochures, and advertisements for a variety of organi study, all of which have been well documented in zations and institutions. However, the time lag implicit studies of leadership, are cited in comprehensive in the statement reveals a misunderstanding about resources on leadership, and provide a good overview youth leadership; after all, aren’t today’s youth today’s of the range of interpretations possible when analyz leaders? Young leaders are less like dormant seeds and ing leadership. These perspectives include the person more like saplings that need nurturing, pruning, and ality, formal, democratic, political, subjective, ambigu strengthening to develop. ity, moral, and the cultural/symbolic perspectives The youth leadership garden can be tended right (Table 1). In the process, I looked for the answers to now by providing growing leaders with young adult four questions: (1) What leadership perspectives are novels in which young people are putting their evident? (2) Which perspectives are dominant? (3) leadership skills and perspectives Does the portrayal of the perspec into practice (Hanna, 1964; Hayden, tives change over time? (4) Does 1969; Friedman & Cataldo, 2002). the gender of the protagonist have What better books for this -

All Roads Lead to South Street Another Police Shooting

jnu JWCCCIHIMJF Daley's Hispanic Democratic Org. All Roads Lead to South Street Member Indicted th Prosecutors announced an indict ment in the inquiry of the hiring 13 Year Anniversary And Fundraiser practices of Mayor Daley's political organization. In this gutsy and bold move, the prosecutors indicted a Saturday, December 9th Hispanic Democratic Organization (HOD) coordinator for lying. The Hispanic Democratic Or ganization, a powerful street team for Mayor Daley, is being investi gated for hitting up city officials for jobs for the HDO. John Resa, a worker in the Water Management Department, pleaded not guilty to lying about seeking city jobs as \rewards for campaign workers. Hundreds of workers in the HDO received jobs with the city in those oh-so-desirable jobs in the water department and streets and sanita tion department. Resa was put on paid administrative leave following Follow the leaders, Cheryle Jack- derman Arenda Troutman; Rev. Al Bill "Dock" Walls and Clerk of the Year Anniversary and fundraising the indictment. Resa just returned to son, new president of the Chicago Sampson (ordained by Dr. Martin Circuit Court Dorothy Brown; Illi affair for The South Street Journal work for the city from disability Urban League; 3rd Ward Alderman Luther King, Jr); Morgan Carter nois State Senator Kwame Raoul; Newspaper. leave on November 15th as a watch Dorothy Tillman, Eddie Read, presi ("The World's Conversation and the list goes on and on, and we man. dent of The Black Independent Po Starter"); Park National Bank's Bill hope that many others will follow the (Continued on page 3) litical Organization; 20th Ward Al- Norels; Chicago Mayoral Candidates leaders and supporters to the 13th (Continued on page 8) Community activist "Queen Sis Inside South Street ter" confronts a Chicago Police Officers after a man was shot by the police after he refused to drop his weapon. -

Follow the Leaders

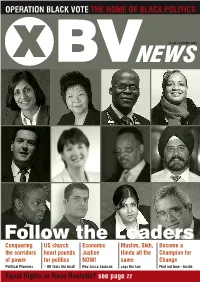

OPERATION BLACK VOTE THE HOME OF BLACK POLITICS ISSUE 2 AUTUMN 2007 Follow the Leaders Conquering US church Economic Muslim, Sikh, Become a the corridors heart pounds Justice Hindu all the Champion for of power for politics NOW! same Change Political Pioneers – UK feels the beat! Rev Jesse Jackson says the law Find out how - inside AUTUMN 2007 1 Equal Rights or Race Roulette? see page 22 Editor’s Contents 04 News from OBV A note from Director Simon Woolley Note 08 Political firsts Year end review of politicians making history by taking government positions Cheers to the pioneers Two thousand and seven has been a good year for political 04 firsts, clinking glasses resound up and down Westminster’s 10 Party Political Broadcast heavy-panelled corridors. Hugh Muir assess the main parties’ commitment to the black electorate Shahid Malik MP became the first Muslim Minister; Baroness Patricia Scotland the first woman Attorney General; Baroness Sayeeda Warsi the first Asian woman 12 Under one law past the post as a Shadow Minister. And Diane Abbott Government laws and public reprisals are unfairly targeting and alienating Britain’s Asian winning election after election culminated this summer in communities reports Aditi Khanna the popular MP’s celebration of 20 years in the Commons. Cllr Rotimi Adebari Adebari was appointed Ireland’s first 15 Connecting Communities Black mayor; Mohammad Asghar became the first ethnic Cllr Abdul Malik and Westminster hopeful minority Welsh Assembly member and Anna Manwah Lo Floyd Millen tells why a role in politics is a must the first person of Chinese origin to be selected into the Northern Ireland Assembly. -

Sunday Workshops Sunday J

WORKSHOP DESCRIPTIONS START ON PAGE 60 SUNDAY WORKSHOPS PERIOD 7 – 10:00 - 11:30 AM PERIOD 8 – 1:00 - 2:30 PM 7-01 Rejoice and Be Glad: (Y)Ours is the 8-01 Thirsting for Justice: Teaching Virtues 8-15 I’ve Been at This a Long Time Now (*) Kingdom of God! - David Haas as Tools for Change (*) - David Wells - Jesse Manibusan 7-02 Sign of the Times: A Review of the World- 8-02 Is Your Parish Ready to Grow Young? (*) 8-16 Life IS a Mission (*) - Ted Miles wide Catholic Landscape (*) - Leisa Anslinger 8-17 A Ministry of Presence: Accompanying - John Allen Jr. 8-03 Justice to and from the Peripheries (*) Those Who’ve Suffered the Death of a - 7-03 Reflections Through Music and Movement Dr. Ansel Augustine Loved One to Homicide (*) (*) - Monica Luther & Nicole Masero 8-04 The Care and Feeding of Catechists: Seven - Suzanne Neuhaus 7-04 The Art of Storytelling (*) Simple Strategies to Honor, Inspire and 8-18 Technology Evangelizers of the Gospel (*) - Mary Birmingham Motivate Your Catechists! (*) - Nancy Bird - Paul Sanfrancesco 7-05 The Power of Possibility: The Untold Story 8-05 Wine and Dine with Jesus: The Greatest (*) - Sean Callahan Invitation of Your Life (*) 8-19 Athirst is My Soul for God: Prayer and - Sr. Kathleen Bryant Children with Disabilities (*) 7-06 Unexpected Occasions of Grace (*) - Sr. Kathleen Schipani - Dr. Michael Carotta 8-06 Sing for Justice: Songs Proclaiming God’s Love and Mercy (*) - John Burland Whose Reflection Do You See in the Mirror? 7-07 Liberating Christian Spirituality (*) 8-20 - Prof. -

American Indian Songs of Today AFS

The Library of Congress Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division Recording Laboratory AFS L36 MUSIC OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN INDIAN SONGS OF TODAY From the Archive ofFolk Culture Recorded and Ed ited by W illard Rhodes First issued on long-playing record in 1954. Accompanying booklet published 1987. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 82-743366. Available from the Recording Laboratory, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540. Cover illustration: THREE EAGLE DANCERS, by Woody Crumbo (Creek-Potawatomi). Photograph courtesy of the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. • Dedicated to the memory of Willard W. Beatty, Director of Indian Education for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of the Interior, from 1937 to 1951. • • FOREWORD TO THE 1954 EDITION • • For a number of years the Bureau of Indian Affairs has sponsored the recording of typical Indian music throughout the United States. During this time approximately a thousand Indian songs have been recorded by Mr. Willard Rhodes, professor of music at Columbia Univer sity. The study originated in an effort to deter mine the extent to which new musical themes were continuing to develop. Studies have shown that in areas of Indian concentration, especially in the Southwest, the old ceremonial songs are still used in the traditional fashion. In the Indian areas where assimilation has been greater, Indian type music is still exceedingly popular. There is considerable creative activity in the development of new secular songs which are used for social gatherings. These songs pass from reservation to reservation with slight change. While the preservation of Indian music through recordings contributes only a small part to the total understanding of American Indians, it is nevertheless an important key to this understand ing. -

Have Henry's Book As a Gift

The Code for New Leaders The Code for New Leaders How to Hit the Ground Running in Days not Weeks Henry Rose Lee Talenttio Books London First Published in Great Britain in 2015 by Talenttio Books Copyright © Henry Rose Lee 2015 The right of Henry Rose Lee to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patent Act 1988. ISBN 978-0-9934516-0-7 (paperback) 978-0-9934516-1-4 (e-book) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the express written permission of the author. This includes reprints, excerpts, photocopying, recording, or any future means of reproducing text. If you would like to do any of the above, please seek permission first by contacting us at [email protected]. Talenttio Books are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programmes. To contact a representative please email us at [email protected]. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lee, Henry Rose The Code for New Leaders: how to hit the ground running in days not weeks Printed and bound in Great Britain To JB ‘Leadership and learning are indispensable to each other’ John Fitzgerald Kennedy About the Author Henry Rose Lee started coaching on the school bus at the age of 12, when she discovered one of her friends in tears over the recent death of her mother. -

The Ithacan, 2008-04-10

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 2007-08 The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 4-10-2008 The thI acan, 2008-04-10 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2007-08 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 2008-04-10" (2008). The Ithacan, 2007-08. 11. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2007-08/11 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 2007-08 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ACCENT STUDENTS BRING SOUL TO CAMPUS, PAGE 15 AN APOLOGY TO DANI STOLLER SPORTS MAN LEADS CLUB FIELD HOCKEY TEAM, PAGE 25 Story portrayed its main source inaccurately, page 12 THIS I SEE ITHACA FARMERS MARKET REOPENS, PAGE 32 Thursday Ithaca, N.Y. April 10, 2008 The Ithacan Volume 75, Issue 25 Freshman Stephanie Torres leads a tour group of prospective students yesterday. EVAN FALK/THE ITHACAN Judge halts roadwork BY KATHY LALUK on each side of the road — a 2-foot NEWS EDITOR expansion in either direction. Th e A county judge ruled in favor road currently has 10-foot lanes of Coddington residents earlier and 3-foot gravel shoulders. this week in a case against the In order to get the construc- County Legislature’s plans to tion under way, the county com- expand the road. pleted a review of the ecological County Supreme Court Justice impact the construction would Robert C. -

Fie Fe FESTIVAL

-- IILL~--I~T-- -- - rý-P r T H E EXCLUSION MACHINE PAGE 2 ARMY/ MATH SUPER I COMPUTER Ii PAGE 5 AM I R I BARAKA'S NEW BOOK PAGE 7 A HISTORY OF THE THREE VILLAGE AREA DAI A6 iEf Ef BACH ARIA FESTIVAL PAGES 10 &11 i i THEATRE PAGE 13 N.L ASBESTOS PAG mmmmmý 'THE EXCLUSION MACHINE' USB Professor Blacklisted From Entering U.S. by Joe DiStefano information which would have for aliens to request removal of warranted the alien's exclusion their names from the "lookout list." The McCarthy Era is dead and regardless of what the judge may Congress recently proposed buried and the Cold War is all but have thought or said." another statute concerning "lookout thawed as far as most Americans Diogenes P. Kekatos, Assistant list" (see New York Times, 6/14/91). can tell. However, vestiges of the U.S. Attorney in charge of the case, Under the proposal the State repressive McCarthy Era linger and said that Yatani's constitutional Department would be required to have had an adverse effect upon the claim is, "...utterly devoid of merit purge the list with the exception of lives of aliens living in the United and borders on the frivolous." those whose presence on the list States. In contrast, Helton believes the proved compelling for national One such individual is USB case is groundbreaking. "The security reasons. Social Psychology Professor lawsuit seeks to remedy a dan- "Congress is growing Choichiro Yatani. As of press time gerous legacy of the Cold War increasingly frustrated with the Yatani awaits a response from the Era...over three hundred thousand Executive's seeming unwillingness State Department and the result of people are subject to exclusion and to dis-establish these obsolescent the Federal Court case that began abuse as long as their names remain look mechanisms," stated Helton. -

I the BG News' Mail-In Form Need Jllli Ooormarv Bartender Ml Urith Drink Purchase Bopngiet SB3 S Man Street

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-10-1985 The BG News October 10, 1985 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 10, 1985" (1985). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4433. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4433 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ,".< Showers today. High in the mid 60s. Vol. 68 Issue 27 THE BG NEWSThursday, October 10,1985 Image key to success, Molloy says by Patti Skinner "You are taught staff reporter values of the lower John Molloy, best-selling au- thor of Dress lor Success ad- middle class, and vises, "Follow the leaders. you are taught to Look, act, and sound like a win- ner." fail." In an interview before the — John Molloy, speech Molloy said the title of his presentation, "Dress for Suc- author of Dress cess" was inappropriate be- for Success cause he stresses overall image rather than dress. Mondale-Reagan proved that He said to be successful stu- people vote on the candidate's dents must emulate the rich, looks, and not because they and think and act like the agree with views on issues. sucessful. Molloy said 90 percent Molloy, who lectures at about of students don't understand the 20 colleges a year, spoke last importance of Image. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

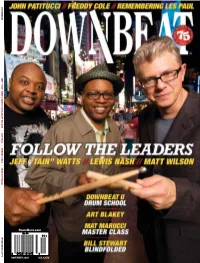

11 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 NOVEMBER 2009NOVEMBER U.K. £3.50 DB0911_01_COVER.qxd 9/16/09 12:48 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT JEFF “TAIN” WATTS/LEWIS NASH/MATT WILSON // LES PAUL // FREDDY COLE // JOHN PATITUCCI NOVEMBER 2009 DB0911_02-05_MAST.qxd 9/17/09 12:30 PM Page 2 DB0911_02-05_MAST.qxd 9/17/09 12:30 PM Page 3 DB0911_02-05_MAST.qxd 9/17/09 12:31 PM Page 4 November 2009 VOLUME 76 – NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

December 2011

!.!-!:).'% 02/ 02):%0!#+!'% 5*.&-&44%36.#00,4t53"7*4#"3,&3 7). &2/-0%!2, VALUED ATOVER $ECEMBER 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 253(S .%), 0%!24 5)&.0%&3/%36..&3*/5&37*&8 (&516#-*4)&% .",&*548*/( 83*5&"(3&"5.&5)0%#00, +";;%36..*/(&44&/5*"-4 */'-6&/$&4 %&&11631-&4 '*7&'*/(&3 *"/1"*$& %&"5)16/$)4 +&3&.:41&/$&3 #-0/%*&4$-&.#63,& -&&%:-6%8*(,/0#5&/4*0/%36.4 3"4$"-'-"554+*.3*-&:800%4)&%%*/( -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% ."1&9#-"$,1"/5)&37&-7&50/&4;*-%+*"/45*$,4$"%&40//"("4)*$0.1"$5,*5(*#3"-5"3)"3%8"3& Volume 35, Number 12 • Cover photo by Andrew MacNaughtan CONTENTS Kaley Nelson Andrew MacNaughtan 32 JEREMY SPENCER In metal circles, crossing over into the mainstream can be viewed with suspicion. The musicians in Five Finger Death Punch, however, happily back up their hard-earned popularity with chops for days and songs that work. “Come to the show! Buy the record!” says their drummer. “I welcome that with open arms.” by Billy Brennan 52 25 TIMELESS DRUM BOOKS An exclusive survey of the drumming method books that have stood the test of time. Your drum library starts here. 40 NEIL PEART A new DVD puts us right on stage with the Rush rhythmatist, for a detailed throne-side look at drumming masterpieces from his fruitful career. Here, MD digs deep into Peart’s musical travelogue, including his recent excursions EJ DeCoske into the unknown. This Time Machine makes all stops…. by Michael Parillo 12 UPDATE • Unearth/Killswitch Engage’s JUSTIN FOLEY • Charred Walls of the Damned’s Kenny Gabor RICHARD CHRISTY • Skillet’s JEN LEDGER 56 GET GOOD: WRITING A 30 WOODSHED Rascal Flatts’ JIM RILEY: Drum Dojo DRUMMING METHOD BOOK The instructional-book market is more competitive than ever.