Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Proposal

BUSINESS PARTNERSHIP PROPOSAL “FIRST TIME IN INDIA” New Delhi, INDIA 21st - 23rd AUGUST, 2020 ORGANISED BY NEXODE MEDIA PVT. LTD. ABOUT GLOBAL YOUTH LEADERS MODEL UNITED NATIONS Global Youth Leaders MUN (GYLMUN) will be held on August 21-23, 2020 in New Delhi, India. GYLMUN is aimed to provide a platform for youth to learn about diplomacy, critical thinking, public speaking and the United Nations Conference. The ultimate goal of GYLMUN is to encourage the youth to be aware of the international issues, understand and try to form a possible solution to solve particular issues related to the 17 Global Goals. The youth will feel the ambience of being representatives of their assigned countries and experience how the United Nations Conference executes their ideas and plans. It is the best platform where they can improve their soft skills and knowledge and expand their network. ABOUT GLOBAL YOUTH LEADERS MODEL UNITED NATIONS As an important part of the world, youth have responsibilities and rights to contribute to the realization of Global Goals as a key to transform our world into a better place to live in. As a youth capacity development platform, Nexode Media has consistently put effort to arrange some programs that are relevant to youth in today's need and for the better future of the world. The organization is eager to create a platform, form an alliance between young leaders, which will accommodate ideas from youth spread all over the countries through the programs. Youth leaders will get more perspectives from the world, thus, they will enhance more understanding about related issues. -

Consolidated List of Article 13 Health Claims List of References Received by EFSA

Unit on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies Parma, 5 April 2011 Consolidated list of Article 13 health claims List of references received by EFSA Part 3 IDs 2001 – 3000 (This document contains the list of references for claims which the Commission has asked EFSA to prioritise in the evaluation.) BACKGROUND In accordance with Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061 Member States had provided the European Commission with lists of claims accompanied by the conditions applying to them and by references to the relevant scientific justification by 31 January 2008. EFSA has received from the European Commission nine Access databases with a consolidated list of 4,185 main health claim entries with around 10,000 similar health claims. The similar health claims were accompanied by the conditions of use and scientific references. The nine Access databases were sent in three batches - in July 2008, in November 2008 and in December 2008. Subsequently, EFSA combined the databases into one master database and re-allocated upon request of the Commission and Member States similar health claims which had been accidentally placed under a wrong main health claim entry (misplaced claims). During this process some Member States also identified a number of similar health claims which still needed to be submitted to EFSA (―missing claims‖). These similar claims were also added to the database. In March 2010, the European Commission forwarded to EFSA an addendum to the consolidated list containing an additional 452 main entry claims which have been added to the updated final database which was published on the EFSA website in May 2010 (containing 4,637 main entry claims). -

Gfriend Time for the Moon Night Download Album

gfriend time for the moon night download album GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) PERINGATAN!! Gunakan lagu dari GO-LAGU sebagai preview saja, jika kamu suka dengan lagu GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) , lebih baik kamu membeli atau download dan streaming secara legal. lagu GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) bisa kamu dapatkan di Youtube, Spotify dan Itunes. DETAILS LIRIK DESKRIPSI REPORT. Title GFRIEND - Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) Artist GFRIEND Album Memoria / Yoru (Time for the moon night) - Single Tahun 2018 Genre KPOP Waktu Putar 3:51 Jenis Berkas Audio MP3 (.mp3) Audio mp3, 44100 Hz, stereo, s16p, 128 kb/s. this is my first time to do a Japanese Video with translation. I hope you guys will like it. The Japanese version is sadder, my heart huhuhu! The Trilogy of the "Unrequited Love Theme Song" are now complete. Please check ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Ver.) カラオケ/Karaoke/Instrumental with lyrics here: https://youtu.be/Lt7T-pU8yJE Please check out 여자친구 (GFRIEND) - Memoria (夜) 노래방/Karaoke/Instrumental with bg vocals here: https://youtu.be/8gpD8_iv4TI. I DO NOT OWN ANYTHING. NO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT INTENDED. CREDITS GOES TO SOURCE MUSIC. (ジーフレンド) GFriend - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (ジーフレンド) Japan Single 'Memoria / 夜 (Time for the Moon Night)' ジーフレンド (GFRIEND) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) Japanese ジーフレンド (GFRIEND) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) Japanese Version ジーフレンド (GFRIEND) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) Japanese Version Kanji/Rom/English Lyrics (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/English Lyrics (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/English Sub (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/English Translation (여자친구) ジーフレンド (GFriend) - 夜 (Time for the Moon Night) (Japanese Version) Kanji/Rom/Eng Sub Trans. -

Products; Organization and Efficiency; Store Di*Lays; Conditioning Appendd. Both Black and White and Color Photographs Illustrat

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 330 809 CE 057 462 AUTHOR Anderson, Gary A. TITLE Floral Design and Marketing. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., ColUmbus. Agricultural Curriculum Materials Service. SPONS AGENCY Ohio State Dept. of Education, Columbus. Agricultural Education Service. PUB DATE e8 NOTE 858p.; Photographs will not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROMOhio Agricultural Education Curriculum Materials Service, 254 Agricultural Administration Bldg., Ohio State University, 2120 Fyffe Road, Columbus, OH 43210-1099 . PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC35 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; Advertising; *Agricultural Education; Design; *Distributive Education; *Floriculture; *Marketing; *Ornamental Horticulture Occupations; Plant Identification; Postsecondary Education; Salesmanship; Sales Occupations; *Sales Workers IDENTIFIERS *Floral Designers; Florists ABSTRACT This profusely illustrated, 32 chapter book surveys retail floriculutre and makes a current statement of the industry. It can be used by students pursuing individualized study, in a classroom with instructor reinforcement and demonstrations, and by a former student or flower shop employee as a refresher tool and reference. Principles of flower arranging are explained and applied. Identification of floral material and supplies commonly found in flower shops is explained with illustrations. Information on care, handling, and selling of flowers is provided. Suggested activities in each chapter provide hands-on exercises. -

Report Artist Release Tracktitle TV2 Flow Tv 2016 Bubber & Britt Larsen

Report Artist Release Tracktitle TV2 flow tv 2016 Bubber & Britt Larsen Endlose Liebe Endlose Liebe TV2 flow tv 2016 Deichkind Befehl von ganz unten Leider geil TV2 flow tv 2016 Lowrider Betty New Generation Crawling Back to Life TV2 flow tv 2016 Snatch Aka Podfu(C)K We're going to London SCENE We're going to London SCENE TV2 flow tv 2016 Sway & King Tech Wake up Show Freestyles, Vol. 3 Wake up Show Promo (feat. JAY-Z) TV2 flow tv 2016 Szhirley, Allan Simonsen, Niels Olsen Tam Tam revy 2014 Allan i verden TV2 flow tv 2016 Ultraviolet Sound Ultraviolet Sound Girl Talk Best Song Ever (Originally Performed By One TV2 on demand 2016 2 Go Karaoke Hits (Karaoke Version) Direction) TV2 on demand 2016 2 Unlimited No Limits Tribal Dance TV2 on demand 2016 7Horse Let the 7Horse Run Meth Lab Zoso Sticker TV2 on demand 2016 A. Peter Kingslow Come Back To Me Come Back To Me TV2 on demand 2016 Against Me! White Crosses / Black Crosses I Was A Teenage Anarchist TV2 on demand 2016 Alt Backline The Sound of Silence (Instrumental) - Single The Sound of Silence Instrumental TV2 on demand 2016 Ameritz Only By The Night Use Somebody Tell Me (David August Remix) [feat. Dennis TV2 on demand 2016 Andre Crom Tell Me - Single Degenhardt] TV2 on demand 2016 Andrew John Glen What's On - Film, TV & Radio Vol. 3 Doki and the food chain Andy Gonzales, Gary Joseph Romero, John TV2 on demand 2016 Carrasco Latin-Reggae-World Salsa Party TV2 on demand 2016 Annie Anniemal Chewing Gum Thanksgiving Fireside Collection: Family Favorites The Four Seasons, Concerto No. -

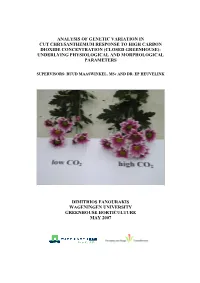

(Closed Greenhouse): Underlying Physiological and Morphological Parameters

ANALYSIS OF GENETIC VARIATION IN CUT CHRYSANTHEMUM RESPONSE TO HIGH CARBON DIOXIDE CONCENTRATION (CLOSED GREENHOUSE): UNDERLYING PHYSIOLOGICAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL PARAMETERS SUPERVISORS: RUUD MAASWINKEL, MSc AND DR. EP HEUVELINK DIMITRIOS FANOURAKIS WAGENINGEN UNIVERSITY GREENHOUSE HORTICULTURE MAY 2007 © 2007 Wageningen, UR Glastuinbouw Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen of enige andere manier zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van Praktijkonderzoek Plant & Omgeving. Wageningen UR Glastuinbouw is niet aansprakelijk voor eventuele schadelijke gevolgen die kunnen ontstaan bij gebruik van gegevens uit deze uitgave. Projectnummer: 3242008100 Wageningen UR Glastuinbouw Adres : Violierenweg 1, Bleiswijk : Postbus 20, 2665 ZG Bleiswijk Tel. : 0317 – 485 606 Internet : www.glastuinbouw.wur.nl CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT .................................................................................. 4 GENERAL INTRODUCTION.................................................... 5 Growth and development of chrysanthemum in enriched CO 2 regimes......................... 5 CO 2 concentration........................................................................................................... 6 Adaptation to the high [CO 2] ......................................................................................... -

Is There a Specific Stage to Rest? Morphological Changes in Flower Primordia in Relation to Endodormancy in Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium L.)

Is there a specific stage to rest? Morphological changes in flower primordia in relation to endodormancy in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) Erica Fadón 1-2, Javier Rodrigo 1, and Maria Herrero 2 1 Centro de Investigación y Tecnología Agroalimentaria de Aragón. Instituto Agroalimentario de Aragón - IA2 (CITA-Universidad de Zaragoza), Av. Montañana 930, 50059 Zaragoza, Spain 2 Estación Experimental Aula Dei, CSIC, Av. Montañana 1005, 50059 Zaragoza, Spain ORCID: 1 0000-0002-8321-1764; 2 0000-0002-3499-1602; Corresponding autor: [email protected], +34 976716314 Abstract In temperate woody deciduous perennials, dormancy is a survival strategy to persist winter temperatures; but chilling is also required for the release of flower bud dormancy and for the completion of flower development. This was noticed over hundred years ago, but the biological mechanisms underlying cold regulated dormancy and its release remain poorly understood. That chilling is required for the completion of flower development led us to hypothesize that a particular stage of flower development may be consistently associated with the dormant phase of flower bud development. Flower development of five sweet cherry cultivars was examined weekly under stereoscopic and optical microscopes over three years. Chilling requirements for each cultivar were determined by placing weekly shoots in forcing conditions. The establishment of a flower developmental scale showed that early and late flower development, in the autumn and spring, were asynchronous among cultivars and years. However, in all circumstances, dormancy occurred at the same stage of flower development, characterized by the presence of all flower whorls, with the anthers clearly differentiated in the four locules, and the pistil showing an incipient ovary, style and stigma. -

Songs in the Key of Z

covers complete.qxd 7/15/08 9:02 AM Page 1 MUSIC The first book ever about a mutant strain ofZ Songs in theKey of twisted pop that’s so wrong, it’s right! “Iconoclast/upstart Irwin Chusid has written a meticulously researched and passionate cry shedding long-overdue light upon some of the guiltiest musical innocents of the twentieth century. An indispensable classic that defines the indefinable.” –John Zorn “Chusid takes us through the musical looking glass to the other side of the bizarro universe, where pop spelled back- wards is . pop? A fascinating collection of wilder cards and beyond-avant talents.” –Lenny Kaye Irwin Chusid “This book is filled with memorable characters and their preposterous-but-true stories. As a musicologist, essayist, and humorist, Irwin Chusid gives good value for your enter- tainment dollar.” –Marshall Crenshaw Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. But, believe it or not, they’re worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure, and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. Irwin Chusid is a record producer, radio personality, journalist, and music historian. He hosts the Incorrect Music Hour on WFMU; he has produced dozens of records and concerts; and he has written for The New York Times, Pulse, New York Press, and many other publications. $18.95 (CAN $20.95) ISBN 978-1-55652-372-4 51895 9 781556 523724 SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z Songs in the Key of Z THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF O U T S I D E R MUSIC ¥ Irwin Chusid Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chusid, Irwin. -

One, Two, Three! Two, One

One, Two, Three! David Adams holds a Ph.D. in Art History Education and currently teaches art history at Sierra College in California. Since 1974 he has periodically taught and administered in several Waldorf schools, spending more than nine years working in the diverse roles of class teacher, special subjects teacher, high school One, Two, Three! David Adams teacher, remedial teacher, and school administrator. He has published a num- ber of articles on Waldorf education and has also taught art history at sev- A Collection of Songs, Verses, eral state universities and art schools. The selection of material in this book for children in the first three grades is drawn from his years as a class teacher Riddles, and Stories for and music teacher in three different schools. It is the author's hope that both Children of Grades 1-3 teachers and parents will find these songs, stories, verses, and riddles useful, and that they will continue to delight future generations of children. by David Adams AWSNA Publications AWSNA The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America Publications Office 3911 Bannister Road Fair Oaks, CA 95628 Cyan Black Magenta Yellow 2 ONE, TWO, THREE! A COLLECTION OF SONGS, VERSES, RIDDLES, AND STORIES FOR CHILDREN OF GRADES 1-3 by David Adams 3 Published by: The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America 3911 Bannister Road Fair Oaks, CA 95628 Title: One, Two, Three A Collection of Songs, Verses, Riddles, and Stories for Children of Grades 1-3 Author: David Adams Editor: David Mitchell Proofreader: Ann Erwin Cover: Hallie Wootan © 2002 by AWSNA ISBN # 1-888365-35-8 Curriculum Series The Publications Committee of AWSNA is pleased to bring forward this publication as part of its Curriculum Series. -

Productvoorraad

Productvoorraad Hieronder vind je een moment opname van de voorraad op 07-10-2021. Titel Artiest Voorraad Mo'Complete - Vol.2 AB6IX 678 Standard Soft Sleeve 10stk Ultra Pro 173 No Easy [Limited Edition] Stray Kids 157 STICKER Rood (Poster) NCT127 75 Zero Fever Part. 3 Groen (Poster) Ateez 60 Zero Fever Part. 3 Blauw (Poster) Ateez 60 Zero Fever Part. 3 Oranje (Poster) Ateez 60 Skool Luv Affair 2nd Mini Album : Special BTS 59 Addition (Poster) Stray Kids - No Easy (Poster SET) --- 40 Titel Artiest Voorraad ATEEZ - Fever pt2 - Blauw (Poster) --- 39 BTS - Skool Luv Affair (Poster) --- 38 Ateez - Fever pt 2 - Rood (Poster) --- 37 No Easy (Poster B Type) Stray Kids 31 No Easy (Poster C Type) Stray Kids 30 No Easy (Poster D Type) Stray Kids 30 Twice - Taste Of Love - Wit (Poster) --- 24 STICKER Seoul City (Poster) NCT127 24 Eternal Groen (Poster) Young K 24 No Easy (Poster A Type) Stray Kids 22 Treasure - Effect (Poster) --- 21 EXO - Don't Fight The Feeling - Groep --- 21 (Photobook Ver.) Poster BTS - Butter - Strand (Poster) --- 19 Day6 - Gluon (Poster) --- 17 True Beauty - Original Sound Track (Poster) --- 17 Titel Artiest Voorraad Vol.3 [STICKER] (Sticker ver) (Photobook NCT 127 17 ver) Got7 - Last piece roze liggend (Poster) --- 16 Twice - Taste Of Love - Donker Blauw --- 16 (poster) BTS - Butter - Dieven (Poster) --- 16 BTS - Official Lightstick Map Of the Soul --- 15 Twice - Taste Of Love - Pink (poster) --- 14 LOONA - & - Deur (Poster) --- 14 Dreamcather - Road to Utopia (Poster) --- 13 DAY6 - Negentropy - Wonpil (Poster) --- 13 Treasure - [THE FIRST STEP : CHAPTER --- 12 TWO] (Poster) DAY6 - Negentropy - YoungK (Poster) --- 12 Mixtape Stray Kids 11 Shinee - z-w staand (Poster) --- 11 DAY6 - Negentropy - Sungjin (Poster) --- 11 Dystopia : Road To Utopia (D ver) DreamCatcher 10 Titel Artiest Voorraad Seventeen - Your Choice - IJs (poster) --- 10 A.C.E - Siren: Dawn - Blauw (Poster) --- 10 Memories of 2020 BLU-RAY BTS 10 Oneus - Binary Code - Blauw (Poster) --- 9 Twice - More & More - C Ver. -

Kpop Album Checklist My Bank Account Says Nope but My Boredness Told Me to Make It Babes Xoxo

KPOP ALBUM CHECKLIST MY BANK ACCOUNT SAYS NOPE BUT MY BOREDNESS TOLD ME TO MAKE IT BABES XOXO 2NE1 - First mini album 2NE1- Second mini album 2NE1 - To anyone 2NE1 - Crush 2NE1 - Nolza (Japan) 2NE1 - Collection (Japan) 2NE1 - Crush (Japan) 3YE - Do my thang (Promo) 3YE - Out of my mind (Promo) 3YE - Queen (Promo) 4MINUTE - 4 Minutes left 4MINUTE - For muzik 4MINUTE - Hit your heart 4MINUTE - Heart to heart= 4MINUTE - Volume up 4MINUTE - Name is 4minute 4MINUTE - 4minute world 4MINUTE - Crazy 4MINUTE - Act 7 4MINUTE - Diamond (Japan) 4MINUTE - Best of 4minute (Japan) 4TEN - Jack of all trades 4TEN- Why (Promo) 9MUSES - Sweet rendevouz 9MUSES - Wild 9MUSES - Drama 9MUSES - Lost (OOP) 9MUSES- Muses diary part 2 : Identity 9MUSES - Muses diary part 3 : Love city 9MUSES - 9muses S/S edition 9MUSES - Lets have a party 9MUSES - Dolls 9MUSES - Muses diary (Promo) AFTERSCHOOL - Virgin AFTERSCHOOL - New schoolgirl (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - Because of you AFTERSCHOOL - Bang (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - Red/Blue (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - Flashback (OOP) AFTERSCHOOL - First love AFTERSCHOOL - Playgirlz (Japan) AFTERSCHOOL - Dress to kill (Japan) AFTERSCHOOL - Best (Japan) AILEE - Vivid AILEE - Butterfly AILEE - Invitation AILEE- Doll house AILEE - Magazine AILEE - A new empire AILEE - Heaven (Japan) AILEE - U&I (Japan) ALEXA - Do or die (Japan) ANS - Boom Boom (Promo) ANS - Say my name (Promo) AOA - Angels knock AOA - Short hair (OOP) AOA - Like a cat AOA - Heart attack AOA - Good luck AOA - Bingle bangle AOA - New moon AOA - Angels story AOA - Wanna be AOA - Moya AOA -

PROCEEDINGS of the International Lilac Society

Lilacs Volume 10 PROCEEDINGS of the International Lilac Society Tenth Annual Convention Des Moines, Iowa May 21 and 23, 1981 Volume 10 PROCEEDINGS 1981 A publication of THE INTERNA TIONAL LILAC SOCIETY Copyright 7987 Editor, !.L.S. LILACS is the official publication of the International Lilac Society. Proceedings published annually. Research publications as received. THE PROCEEDINGS are benefits of membership. Copies of this publication are available by writing to the Interna- tional Lilac Society, cia Fr. John L. Fiala, 7359 Branch Road, Medi- na, Ohio 44256. Enclose $5.00 per copy requested. President: Dr. Owen M. Rogers University of New Hampshire, Dept. of Plant Science, Nesmith Hall, Durham, N.H. 03824 International Lilac Society, William A. Utley, Executive Vice President, Grape Hill Farm, 1232 Tyre Rd., Clyde, NY 14433 Secretary: Walter W. Oakes" Box 315, Rumford, Maine. 04276 Treasurer: Mrs. Marie Chaykowski 4041 Winchell Road, Mantua, Ohio. 44255 Editor: Robert B. Clark Cattle Landing Road, Meredith, N.H. 03253 MEMBERSHIP CLASSIFICA TION Single annual $ 7.50 U.S. Family 10.00 Sustaining 15.00 Institutional/Commercial 20.00 Life 150.00 * Mail membership dues to l.L.S. Secretary. INTERNA TIONAL LILAC SOCIETY is a non-profit corporation com- prised of individuals who share a particular interest, appreciation and fondness for lilacs. Through exchange of knowledge, experience and facts gained by members it is helping to promote, educate and broaden public understanding and awareness. Published January 1982 J& J Printing,lnc.,laconia,N. H. Contents First Ten Years in Brief 1 Lilac Growing at Margaretten Park 3 Ewing Park's Lilac Collection 6 Des Moines Botannical Center 8 Lilac Clinic 9 Arie F.