Lundy's Lost Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

Planning Statement 17.5.2021 Copy

Proposed extension to the agricultural shed at Raginnis Farm Mousehole Planning and Access Statement and Flood Risk Assessment 17 May 2021 Peggy Rickaby BA Dip Arch RIBA Chartered Architect Milldowns Cottage Ladydowns Newmill Penzance TR20 8UZ Telephone 01736 796952 e-mail [email protected] 1 Introduction 1.1 Raginnis Farm is on the west side of the settlement of Raginnis which is just under a kilometre south west of Mousehole, the OS grid reference is SW4648 2584, the postcode of a nearby property is TR19 6NJ. 1.2 The modern shed which is to be extended is within the boundary of the farm complex and to the west and north of existing relatively modern framed farm buildings. 1.3 The site lies within the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the Heritage Coast and a Nitrate Vulnerable Zone (NVZ). None of the immediately surrounding buildings are Listed. 2 Planning History 2.1 The existing shed was approved under Planning consent number PA17/07699 dated 10 October 2017. 3 Proposals 3.1 The Applicants wish to build an extension against the south gable of their existing shed. 3.2 This statement should be read in conjunction with architect’s drawing numbers THMT 5. 7, 8 and 9. The existing shed 4 Justification for the proposals. 4.1 The Applicants are well established local farmers with a total of about 1100 acres (445 hectares) in West Penwith including 510 acres (200 hectares) at Raginnis and the neighbouring Halwyn, Kemyell and Trevelloe Farms, they have dairy and beef herds as well as arable land. -

Sabrina Times July 2007 Editorial Library This Issue Is a Short One and It's Late

E 17 July 2007 Severnside Branch SSaabbrriinnaa TTiimmeess Branch Organiser's Bit I have just reviewed my last piece for the newsletter and find I made a comment about how the weather would surely be better for our May fieldtrip. How wrong I was! Although the day before had been lovely, Sunday 13th May was very overcast and wet. The Cat's Back was not visible through the cloud but I was impressed by the number of members who turned out in such weather. It was great to see you all. Also, well done and thank you to Duncan who was able to offer us an alternative, lower route, avoiding the cloud if not the rain, and still filled the day with interesting Ever wonder where the exposures. “Sabrina” name comes Our trip to Flat Holm in June was fully booked; from? Here's your answer. as is the week’s trip to Kindrogan in July. Unlike One of a series of carved the Cat's Back trip, the weather for Flat Holm oak statues near the Old was good. It was an excellent day out, and I'd Railway Station, Tintern, like to thank Chris Lee for guiding us. it is dedicated to the Jan and Linda are running a shoestring trip to legend of the Celtic the Sierras in Central Spain in September. goddess, whose latinised There are still spaces on this. In addition to the name is Sabrina. The geology there are many medieval towns in the inset is of the signboard area to explore; not to mention Madrid. -

BIC-1961.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preamble ... ... ... ... ... ... 3 List of Contributors ... ... ... ... ... 5 Cornish Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 Arrival and Departure of Cornish Migrants ... ... 44 Isles of Scilly Notes ... ... ... ... ... 49 Arrival and Departure of Migrants in the Isles of Sciily ... 59 Bird Notes from Round Island ... ... ... ... 62 Collared Doves at Bude ... ... ... ... ... 65 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... 67 The Society's Rules ... ... ... ... ... 69 Balance Sheet ... ... ... ... ... ... 70 List of Members ... ... ... ... ... 71 Committees for 1961 and 1962 ... ... ... ... 84 Index ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 85 THIRTY-FIRST REPORT OF The Cornwall Bird-Watching and Preservation Society 1961 Edited by J. E. BECKERLEGGE, N. R. PHILLIPS and W. E. ALMOND Isles of Scilly Section edited by Miss H. M. QUICK The Society's Membership is now 660. During the year, fifty-one have joined the Society, but losses by death, resignation and removal from membership list because of non-payment of subscriptions were ninety. On February 11th a Meeting was held at the Museum, Truro, at which Mr. A. G. Parsons gave a talk on the identification of the Common British Warblers. This was followed by a discussion. The thirtieth Annual General Meeting was held in the Museum, Truro, on April 15th. The meeting stood in silence in memory of the late Col. Ryves, founder of the Society, and Mrs. Macmillan. At this meeting, Sir Edward Bolitho, Dr. R. H. Blair, Mr. S. A. Martyn and the Revd. J. E. Beckerlegge were re-elected as President, Chairman, Treasurer and Joint Secretary, respectively. In place of Dr. Allsop who had resigned from the Joint Secretaryship, Mr. N. R. Phillips was elected. The meeting also approved of a motion that Col. -

All Notices Gazette

ALL NOTICES GAZETTE CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE ON 20 JUNE 2018 PRINTED ON 21 JUNE 2018 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY | ESTABLISHED 1665 WWW.THEGAZETTE.CO.UK Contents State/2* Royal family/ Parliament & Assemblies/ Honours & Awards/ Church/ Environment & infrastructure/3* Health & medicine/ Other Notices/13* Money/16* Companies/18* People/60* Terms & Conditions/85* * Containing all notices published online on 20 June 2018 STATE STATE Departments of State CROWN OFFICE 3051083THE QUEEN has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the Realm dated 15 June 2018 to appoint Mr. Arvind Michael Kapur, O.B.E., to be Lord-Lieutenant of and in the County of Leicestershire. (3051083) 3051082THE QUEEN has been pleased by Warrant under Her Royal Sign Manual dated 11 June 2018 to appoint John Joseph Bradley as a Recorder under Section 21 of the Courts Act 1971. (3051082) 3051081LEWISHAM EAST CONSTITUENCY Janet Jessica Daby, in the place of Heidi Alexander, who since her initial election has been appointed to the Office of Steward or Bailiff of Our Manor of Northstead in Our County of York. Elaine Chilver (3051081) 2 | CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE ON 20 JUNE 2018 | ALL NOTICES GAZETTE ENVIRONMENT & INFRASTRUCTURE Reference Operator Project Quad/ Direction Name Block Issued ENVIRONMENT & PLA/509 Offshore Thames 52/3 18/04/2018 Design PL370 Engineering Pipeline INFRASTRUCTURE Ltd Operations PLA/520 Premier Oil Catcher 28/9 26/04/2018 E&P UK Pipeline ENERGY Ltd Operations 3051085THE OFFSHORE PETROLEUM PRODUCTION AND PIPE-LINES Main reasons/ Main considerations were discharges to (ASSESSMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS) REGULATIONS conclusions on which the marine environment, deposit of 1999 (AS AMENDED) decision is based materials on the seabed and DIRECTION DECISIONS interference with other users of the sea. -

Flat Holm Island

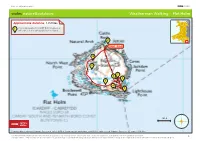

bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles 1 This walk begins in Cardiff Bay where you will catch the boat across to the island. 2 Start / End 10 9 7 8 6 3 4 5 N 500 ft W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to the TV programme only. Routes and conditions may have changed since the programme was made. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check weather conditions before heading out. 1 bbc.co.uk/walesnature © 2010 wales nature&outdoors Weatherman Walking - Flat Holm Approximate distance: 1.2 miles A race against the tide to look at wartime relics and a stunning lighthouse on this beautiful island in the Bristol Channel. 1. The Cardiff Bay Barrage 4. Flat Holm Lighthouse This is where you will catch the boat to the The first light on the island was a simple island. The Barrage lies across the mouth brazier mounted on a wooden frame, which of Cardiff Bay between Queen Alexandra stood on the high eastern part of the island. Dock and Penarth Head and was one of The construction of a tower lighthouse with the largest civil engineering projects in lantern light was finished in 1737. Europe during the 1990s. Today it’s solar powered and the light from its three 100 watt bulbs can be seen up to 16 miles away. -

Listed Buildings Detailled Descriptions

Community Langstone Record No. 2903 Name Thatched Cottage Grade II Date Listed 3/3/52 Post Code Last Amended 12/19/95 Street Number Street Side Grid Ref 336900 188900 Formerly Listed As Location Located approx 2km S of Langstone village, and approx 1km N of Llanwern village. Set on the E side of the road within 2.5 acres of garden. History Cottage built in 1907 in vernacular style. Said to be by Lutyens and his assistant Oswald Milne. The house was commissioned by Lord Rhondda owner of nearby Pencoed Castle for his niece, Charlotte Haig, daughter of Earl Haig. The gardens are said to have been laid out by Gertrude Jekyll, under restoration at the time of survey (September 1995) Exterior Two storey cottage. Reed thatched roof with decorative blocked ridge. Elevations of coursed rubble with some random use of terracotta tile. "E" plan. Picturesque cottage composition, multi-paned casement windows and painted planked timber doors. Two axial ashlar chimneys, one lateral, large red brick rising from ashlar base adjoining front door with pots. Crest on lateral chimney stack adjacent to front door presumably that of the Haig family. The second chimney is constructed of coursed rubble with pots. To the left hand side of the front elevation there is a catslide roof with a small pair of casements and boarded door. Design incorporates gabled and hipped ranges and pent roof dormers. Interior Simple cottage interior, recently modernised. Planked doors to ground floor. Large "inglenook" style fireplace with oak mantle shelf to principal reception room, with simple plaster border to ceiling. -

The Lives of the Saints of His Family

'ii| Ijinllii i i li^«^^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Libraru BR 1710.B25 1898 V.16 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 689 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082689 *- ->^ THE 3Ltt3e0 of ti)e faints REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH ^ ^ «- -lj« This Volume contains Two INDICES to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an INDEX of the SAINTS whose Lives are given, and the other u. Subject Index. B- -»J( »&- -1^ THE ilttieg of tt)e ^amtsi BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &- I NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII I *- J-i-^*^ ^S^d /I? Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &' Co. At the Ballantyne Press >i<- -^ CONTENTS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Princes and Saints . 87-120 Pedigrees of Saintly Families . 121-158 A Celtic and English Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People 159-326 Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints 327 Errata 329 Index to Saints whose Lives are Given . 333 Index to Subjects . ... 364 *- -»J< ^- -^ VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES GIVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

SMP2 6 Final Report

6 ACTION PLAN 6.1 Coastal risk management activities The Action Plan for the Cornwall & Isles of Scilly Shoreline Management Plan review provides the basis for taking forward the intent of management which is discussed and developed through Chapter 4 - and summarised through the preferred policy choices set out in Chapter 5. The SMP guidance states that the purpose of the Action Plan is to summarise the actions that are required before the next review of the SMP however in reality the Action Plan is looking much further into the future in order to provide guidance on how the overall management intent for 100 years may be taken forward. For Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly SMP the Action Plan is a critical element, because there are various conditional policies for later epochs which need to be more firmly established in the future based on monitoring and investigation. The Action Plan can set the framework for an on-going shoreline management process in the coming years, with SMP3 in 5 to 10 years time as the next important milestone. This chapter therefore attempts to capture all intended actions necessary, on a policy unit by policy unit basis, to deliver the objectives at a local level. It should also help to prioritise FCRM medium and long-term planning budget lines. A number of the actions are representative of on-going commitments across the SMP area (for example to South West Regional Coastal Monitoring Programme). There are also actions that are representative of wide-scale intent of management, for example in relation to gaining a better understanding of the roles played by the various harbours and breakwaters located around the coast in terms of coast protection and sea defence. -

Of!Penzance! Book!

! BOROUGH!OF!PENZANCE! BOOK!OF!REMEMBRANCE! BIOGRAPHICAL!DETAILS! ! ! BOER!WAR! 1899!:!1903! ! ! DUNN,!Joseph!Smith.!Lieutenant.!2nd!Regiment,!Scottish!Light!Horse.!Came!to!Penzance!around! 1879!with!his!parents!and!resided!at!Alma!Terrace.!Started!work!as!a!junior!reporter!with!The! Cornishman.!Went!to!South!Africa!and!was!employed!as!a!special!correspondent!for!the!Central! News!of!London.!Twice!captured!by!the!Boers!but!escaped.!Served!in!Ladysmith!during!the!siege.! Accepted!a!commission!in!the!Scottish!Light!Horse.!Married!with!four!children.!Of!a!delicate! disposition!he!died!at!Pretoria!on!13th!of!January!1902!from!an!abscess!of!the!liver!brought!on!by! exposure,!hard!work!and!fatigue.!! ! SIMONS,!Cecil.!Quartermaster!Sergeant.!63rd!Company!(Wiltshire),!16th/1st!Battalion,!Imperial! Yeomanry.!! ! EDWARDS,!Joseph!John!(Jack).!Trooper.!93rd!Company!(3rd!Sharpshooters),!23rd!Battalion,! Imperial!Yeomanry.!Died!of!enteric!fever!at!Charlestown,!Natal!on!15th!of!June!1902!just!short!of! his!21st!birthday.!Completed!an!apprenticeship!as!an!outfitter!with!Messrs!Simpson!and! Company,!Penzance.!Then!moved!to!London!where!18!months!later!he!volunteered!for!active! service!being!associated!with!a!troop!raised!by!the!Earl!of!Dunraven.!Son!of!George!and!Elizabeth! Edwards!of!26!Tolver!Road,!Penzance,!Cornwall.!Listed!on!a!marble!plaque!in!High!Street! Methodist!Church,!Penzance!and!on!his!parents’!headstone!in!Penzance!Cemetery.! ! PAYNTER,!George.!Trooper.!Imperial!Yeomanry.!!! ! ROGERS,!Robert!John.!Private.!13736.!Royal!Army!Medical!Corps.!Died!of!enteric!fever!at!Pretoria! -

Amagical History Tour

coastcoast TRAVEL SLUG THIS PAGE, CLOCKWISE FROM RIGHT Bant’s Carn; the Old Man of Gugh; the lighthouse on Round Island; a mystical offering at the Old Man of Gugh OPPOSITE Would a trip to the ancient sites of the ISLES OF SCILLY deliver the Innisidgen ahoped-for magical respite from the noisehistory and bustle of thetour city? chamber tomb WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Clare Gogerty n antidote to modern city life, plumbing them into ley lines and aligning below – little rocky outbursts fringed by that’s what I was after. Somewhere them with the paths of the sun and moon, swathes of white beaches and breaking far from the whiff of traffic fumes, the so a visit to one usually guarantees a view waves. This is the ‘drowned landscape’ dull hum of the computer and the sigh at the very least. The Scilly Isles bristles written about by historian Charles Thomas, ofA exasperated commuters. Somewhere with prehistory: 60 per cent of land is of who describes a time when the islands quiet, ancient, magical. A place to walk, archaeological importance and it boasts 83 were part of the same landmass before sea breathe deeply and be still. burial chambers. An ancient site with a sea levels rose and engulfed most of it. A time Everything I had heard about the Isles of view and the tingle of otherworldliness was when the Ancients constructed their burial Scilly suggested that it might be the place. what I sought. But would Scilly deliver? chambers on the higher ground, which At the risk of sounding like an old hippy, became the islands we now recognise.